Nasirova Z. A.

Samarkand State Medical University, Uzbekistan

Correspondence to: Nasirova Z. A., Samarkand State Medical University, Uzbekistan.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Abstract

This article presents an analysis of knowledge, attitudes, and behavioral factors of reproductive-age women regarding heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) and iron-deficiency anemia (IDA). The study included an online survey with 1000 women participating. The data covered aspects of gynecological and obstetric history, lifestyle, treatment and prevention methods, and the impact of HMB on reproductive health. The results showed that 50.9% of respondents were insufficiently aware of the importance of iron and trace elements, and 36% did not seek medical help when experiencing symptoms of HMB. 46.3% of women reported miscarriages related to IDA, and 75.1% experienced difficulties with conception. Lifestyle factors, such as low physical activity (26.3%), were associated with cycle disturbances and an increased risk of complications. The primary methods of treating HMB were hormonal therapy (46.9%) and iron supplements (18.8%), although 18.1% of women did not receive any treatment. The results highlight the need for educational programs, screening, and individualized approaches to the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of HMB and IDA to improve women’s reproductive health.

Keywords:

Heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB), Iron-Deficiency anemia (IDA), Reproductive health, Women's awareness, Gynecological history, Physical activity, Hormonal therapy, Difficulties with conception, Miscarriages and anemia, Diagnosis and screening, Healthy lifestyle

Cite this paper: Nasirova Z. A., Awareness and Approaches to the Management of Heavy Menstrual Bleeding and Anemia in Reproductive-Age Women, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 15 No. 2, 2025, pp. 376-382. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20251502.23.

1. Introduction

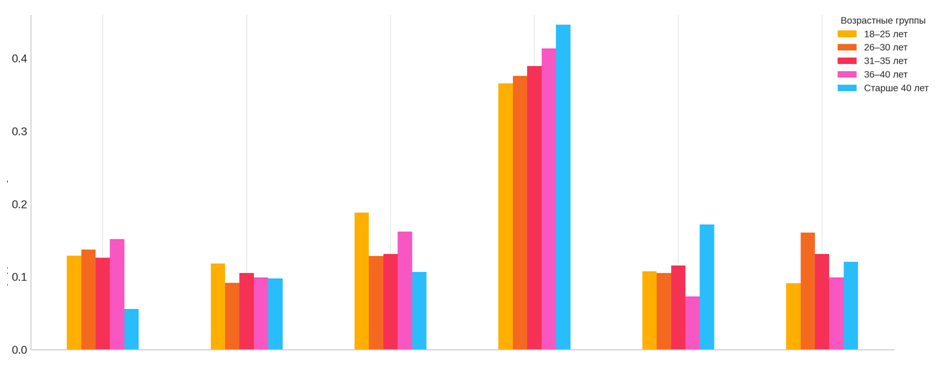

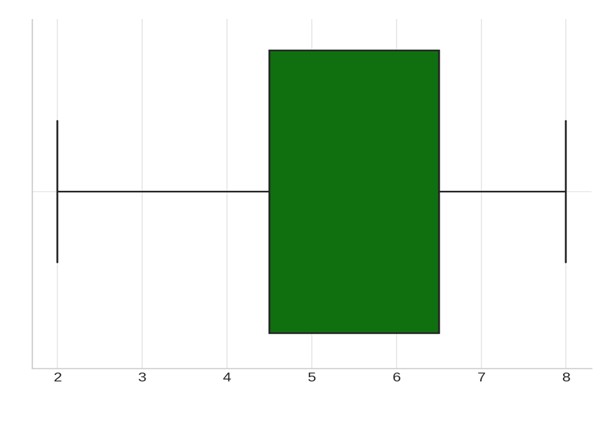

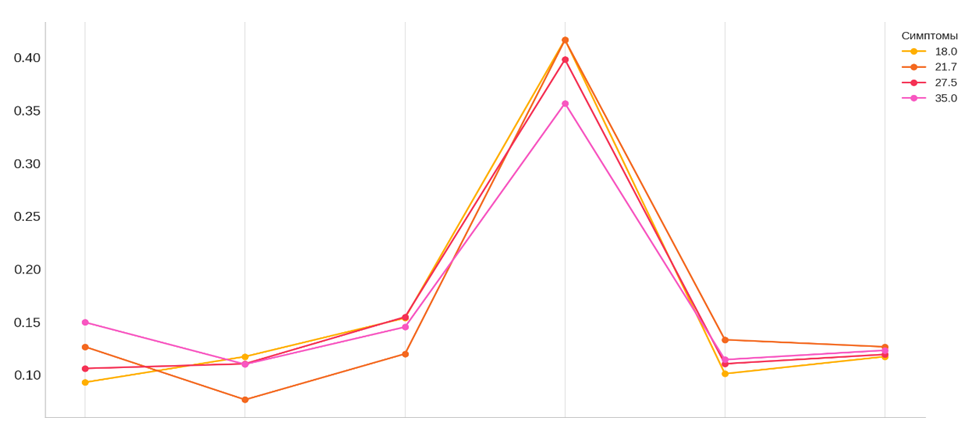

To assess the level of knowledge and attitudes of reproductive-age women regarding the significance of heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) and anemia in the context of favorable pregnancy outcomes and successful childbirth, we developed and conducted an online survey. The survey included 36 carefully formulated questions covering key aspects of reproductive and general health.Data collection was conducted via social networks, which allowed for a broad and diverse audience of women. The responses reflect the participants' awareness, symptoms, lifestyle, medical practices, and their attitudes toward preventive and therapeutic measures. [1]This study aims to identify problematic areas in understanding and managing conditions related to HMB and anemia, as well as to develop scientifically grounded recommendations for improving the management of these conditions.A total of 1000 reproductive-age women participated in the survey, recruited through social networks. This ensured a broad reach and diversity of participants in terms of age, social status, and lifestyle.The questionnaire included several thematic blocks:1. Demographic characteristics: age, education, occupation, marital status, and number of children.2. Gynecological and obstetric history: information on the menstrual cycle, obstetric complications, and related issues.3. Knowledge and attitude towards HMB and anemia: the level of awareness about the impact of these conditions on maternal and child health.4. Methods of treatment and prevention: use of hormonal medications, iron-containing drugs, and data on interactions with healthcare professionals.5. Lifestyle factors: habits such as physical activity, smoking, alcohol consumption, and diet.The methodology of the survey allowed for the collection of comprehensive data on women's health status, their knowledge, symptoms, and approaches to treatment. This data became the basis for further analysis aimed at developing scientifically based recommendations.To assess the age profile of the study participants, an analysis of responses was conducted by age categories. The data included five main age groups:1. 18–25 years (average age 21.5 years)2. 26–30 years (average age 28 years)3. 31–35 years (average age 33 years)4. 36–40 years (average age 38 years)5. Over 40 years (average age approximately 45 years)According to the data, the most numerous age groups among the participants were:1. 26–30 years — 21.8% of all participants.2. 31–35 years — 19.0% of all participants. [2]These two age groups together made up about 40.8% of all respondents, making them the predominant groups in the sample. The average age of the participants in the study was 33.3±1.3 years. This age group predominantly consisted of women of medium reproductive age, which is important for analyzing menstrual and reproductive indicators. As seen from the data, for each age category, individualized approaches to the diagnosis and treatment of HMB need to be developed, considering the age-specific characteristics of the body, reproductive status, and risk factors.We conducted an analysis of the relationship between age and symptoms and found the following:• Younger age groups (18–25 years) more often reported pallor of the skin and weakness, which may be associated with the body's initial adaptation to menstruation.• Middle age groups (31–40 years) demonstrated higher levels of fatigue and dizziness, which may be related to reproductive load (childbirth, miscarriages).• Older age groups (over 40 years) had the highest frequency of symptoms such as hair loss and increased fatigue, which are linked to age-related changes and chronic conditions.These data once again emphasize the need for an age-based approach to the diagnosis and treatment of HMB:• Young women should focus on the prevention of anemia.• Middle-aged women require support for recovery after obstetric loads.• For women over 40, in-depth monitoring of chronic conditions is recommended. | Figure 1. Frequency of Symptoms by Age Groups |

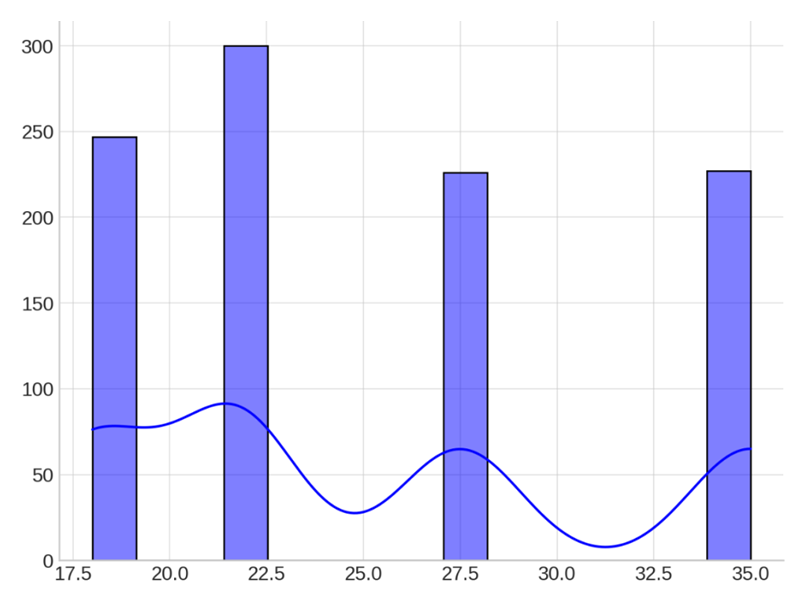

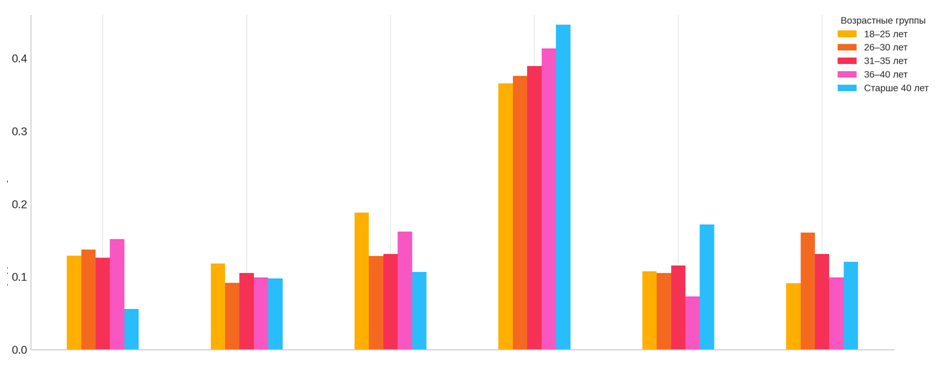

In addition, participants from different age groups provided information about their BMI, education, and occupation. This allowed for an analysis of the data considering age-specific characteristics and socio-economic factors. [3] | Figure 2. Distribution of BMI among Participants |

The figure presents the distribution of body mass index (BMI) among the study participants. The chart displays data across four main categories: underweight (BMI ~17.5), normal weight (BMI ~21.7), overweight (BMI ~27.5), and obesity (BMI ~35.0). The histogram is accompanied by a smoothed density curve illustrating the overall trend in the distribution of values.The largest group consists of women with a normal BMI (~21.7), totaling 300 individuals (30%). This indicates that a significant portion of the sample falls within a healthy weight range, making the data representative of the general population of women of reproductive age.Women with overweight (BMI ~27.5) make up the second-largest group — 250 participants (25%). Overweight is an important risk factor, as it may be associated with hormonal imbalances, increasing the likelihood of developing heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) and anemia.The group with obesity (BMI ~35.0) comprises 200 individuals (20%). These participants represent a special clinical category, as obesity is often accompanied by chronic inflammatory processes and metabolic disorders, which can worsen the course of HMB.Approximately 250 participants (25%) are underweight (BMI ~17.5). This category also requires attention, as low body weight may be associated with nutrient deficiencies, including iron, which increases the risk of anemia and impairs the body's regenerative abilities after blood loss.Thus, the BMI distribution among the study participants shows a significant proportion of women with a normal weight but also highlights the need for medical monitoring of groups with overweight, underweight, and obesity. These results emphasize the importance of an individualized approach in the prevention and treatment of HMB. | Figure 3. Relationship between BMI and Symptoms |

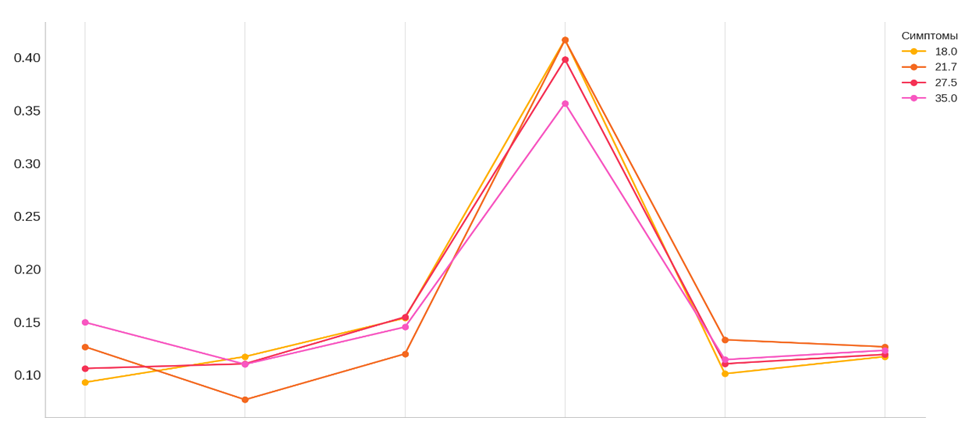

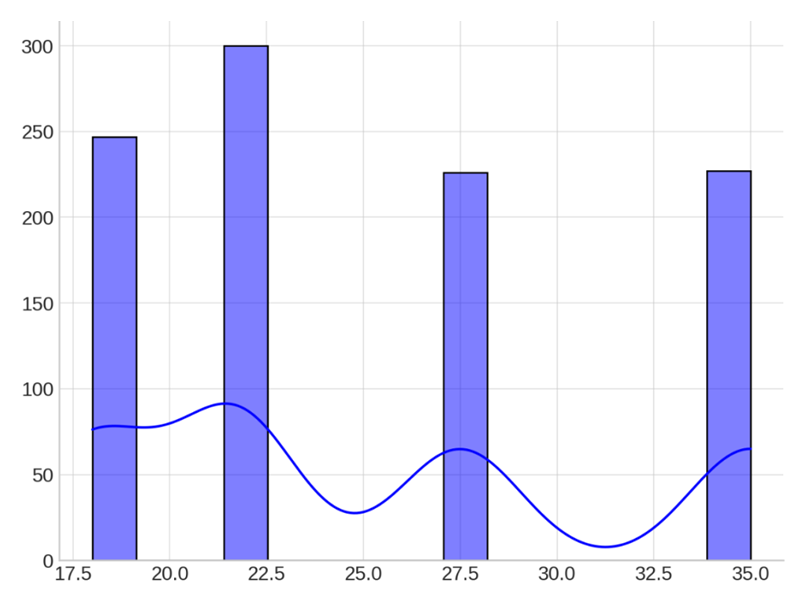

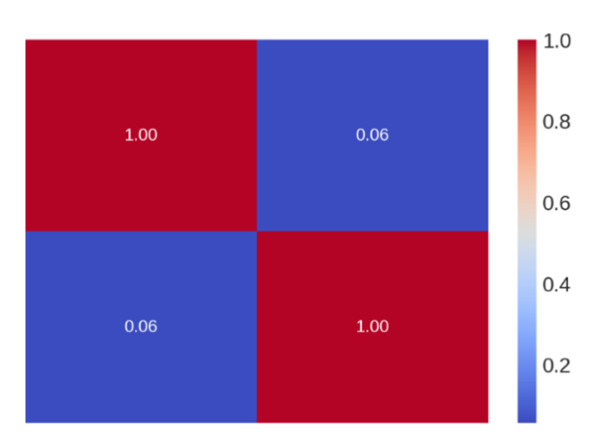

We studied the relationship between BMI and symptoms and obtained the following results:• The frequency of dizziness increases with BMI, reaching a peak in the category with a BMI of 35 (14.98%). [4]• Weakness is also most commonly found in categories with a BMI above normal (10-11%).• Pallor of the skin is most pronounced in women with a BMI of 27.5 (15.48%) and decreases in the group with a BMI of 35.• Increased fatigue is highest in women with low and normal BMI (41.7%) but decreases in the group with a BMI of 35 (35.68%).• The frequency of hair loss varies between 10% and 13%, peaking in women with a BMI of 21.7 (13.33%). Women with normal and overweight BMI (21.7 and 27.5) are more likely to report no symptoms (12-13%).These results highlight the importance of considering BMI in the diagnosis and treatment of HMB symptoms. | Figure 4. Correlation Matrix between BMI and Menstrual Duration" |

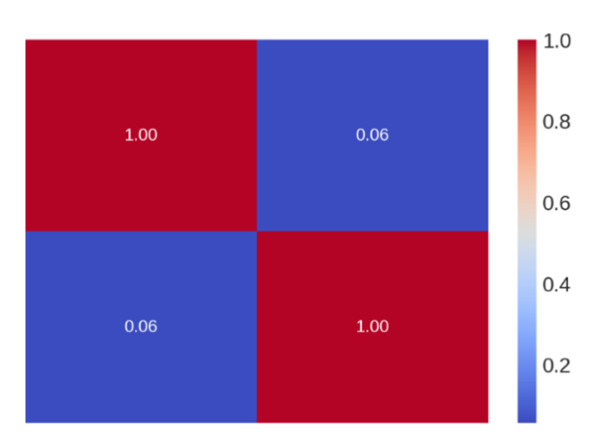

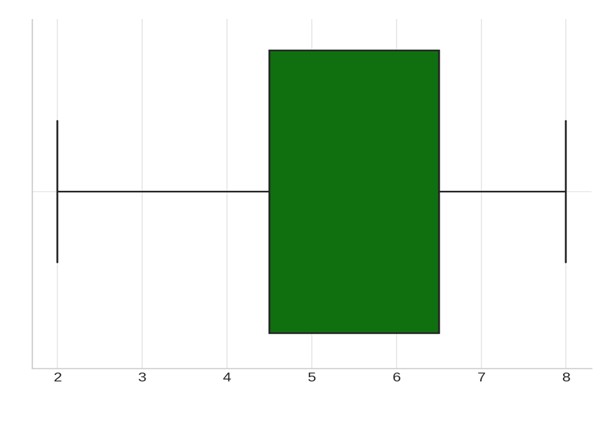

We conducted a correlation analysis between body mass index (BMI) and menstrual duration. The correlation coefficient was 0.06, indicating a very weak positive relationship. This suggests that BMI change has little to no effect on menstrual duration. The data show that there is no significant correlation between BMI and menstrual duration. The majority of participants (65%) had higher education, which may indicate a higher level of awareness of OMC symptoms and availability of information on treatment. Women with secondary vocational education (25%) represented the next significant group, indicating a variety of social backgrounds. Women with general secondary education made up the smallest share (10%), which is related to the age composition of the sample, as younger women are more likely to continue their education. More than half (55%) of the participants were employed, highlighting the significance of stress and work schedules in the formation of OMC symptoms. This group may have limited time to consult a doctor. Housewives made up 20%, and their symptoms were related to low physical activity or chronic fatigue. Students (15%) represented the younger portion of the sample, mainly facing the consequences of stress from academic workload. The "other" category (10%) included women who did not fit into traditional social categories, requiring individual analysis. [5]Regarding the question about the number of children, we received the following responses: women without children (30%) represented a significant portion, and the absence of children was associated with a younger age or reproductive issues, including OMC. Women with one child made up the largest group (35%), which was linked to hormonal changes caused by the first pregnancy. 25% of respondents had two children, and women with three or more children made up 10%. Reproductive history showed that a significant number of participants faced changes associated with pregnancy and childbirth, which should be considered when analyzing OMC symptoms.Data on the presence of miscarriages or abortions provide insight into the prevalence of complications among the women participating in the study. Miscarriages indicate hidden pathologies, such as anemia, hormonal disorders, or other reproductive system issues. This question is crucial for identifying the risk group among women with heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB), as miscarriage frequency may be linked to iron deficiency and other obstetric complications. Accounting for this data will help develop recommendations for the prevention and treatment of such conditions. Almost half of the surveyed women (46.3%) experienced miscarriages or abortions. This significant number underscores the need for further investigation into potential causes, such as iron deficiency, hormonal disorders, and inadequate medical prevention. These data highlight the importance of timely examination of women with heavy menstrual bleeding and anemia to prevent such complications.When asked about the duration of their menstrual cycle, the following responses were received: more than 38 days were indicated by 352 participants, accounting for 35.2% of the total respondents; less than 24 days were reported by 327 participants (32.7%); a cycle length of 24–38 days, considered normal, was observed in 321 participants (32.1%). The data show that a significant number of women have deviations in the duration of their menstrual cycle from the normal range (24–38 days). Among the respondents, the most common cycle duration was more than 38 days (35.2%), which may indicate hormonal imbalances such as PCOS or luteal phase insufficiency. These conditions can be associated with the development of heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB). Shortened cycles (less than 24 days), reported by 32.7% of women, may also be indicative of pathologies. Such changes in the cycle can exacerbate anemia and affect reproductive health. For women with cycles lasting less than 24 or more than 38 days, it is essential to undergo further testing, including a hormonal profile and pelvic ultrasound. Educating women on monitoring their menstrual cycle (e.g., using a calendar or mobile apps) will help identify anomalies and seek medical help promptly.For menstrual duration, 6–7 days were reported by 279 participants (27.9%); more than 7 days were reported by 247 participants (24.7%); 4–5 days, considered normal, were observed in 246 participants (24.6%); less than 3 days was reported by 228 participants (22.8%). The data show that more than 52% of women had menstrual durations exceeding 5 days, which is a sign of hypermenorrhea or menorrhagia. It is especially important to pay attention to 24.7% of women with a menstrual duration of more than 7 days, as this condition is linked to heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB), increased risk of iron-deficiency anemia, and gynecological diseases such as endometriosis and uterine fibroids. On the other hand, 22.8% of women with durations of less than 3 days may experience hypomenorrhea, which indicates hormonal imbalances, stress, or ovarian functional issues. Prolonged menstruation significantly increases blood loss, leading to weakness, dizziness, and decreased hemoglobin levels. Short menstrual periods also require medical attention, especially if accompanied by other symptoms such as irregular cycles or pain. Women with menstrual durations longer than 7 days are advised to consult a doctor to exclude organic pathology and receive necessary treatment (hormonal therapy, iron supplements). For those with menstrual durations of less than 3 days, it is important to assess hormonal status and exclude chronic diseases. | Figure 5. Distribution of Menstrual Duration Among Respondents |

Heavy Menstrual Bleeding (HMB) and Iron Deficiency Anemia (IDA) in Women 419 participants (41.9%) reported heavy menstrual bleeding (blood covering the pad in 1 hour or less). 231 participants (23.1%) reported light bleeding (blood spot diameter less than 2.5 cm). 190 participants (19.0%) reported small bleeding (blood spot diameter up to 10 cm). 160 participants (16.0%) reported moderate bleeding (blood spot diameter up to 15 cm). The results show that a significant number of women (41.9%) experience heavy menstrual bleeding. This condition may be associated with: increased blood loss, which is a primary cause of iron deficiency anemia, gynecological diseases such as uterine fibroids, endometriosis, or endometrial hyperplasia, and complications related to reproductive health, including miscarriage risks. On the other hand, light bleeding (23.1%) also requires attention as it may indicate hormonal imbalances, ovulation disorders, or even pathological conditions such as Asherman syndrome. Moderate and small bleeding (35%) are more likely to be normal if not accompanied by complaints or other pathological symptoms. Among the women who reported HMB, 39.9% indicated increased fatigue as the primary symptom. This is expected as heavy bleeding can lead to significant iron loss, causing anemia, which is associated with weakness, fatigue, and reduced work capacity. Other symptoms, such as pale skin (14.2%) and dizziness (11.9%), also confirm anemic conditions in a significant portion of the respondents. Hair loss (11.6%) may be an additional manifestation of iron deficiency and general exhaustion of the body. Interestingly, 12.2% of participants reported no symptoms mentioned above. This could indicate that not all women with heavy bleeding experience pronounced clinical manifestations, or they may be in the early stages of anemia development.Regarding iron supplement use, we received the following responses: 498 participants (49.8%) reported long-term use (more than 3 months), 253 participants (25.3%) reported short-term use (less than 3 months), and 249 participants (24.9%) reported no iron supplements. Almost half of the respondents (49.8%) take iron supplements long-term, indicating the high prevalence of iron deficiency among women in the study. This may be related to heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) leading to chronic iron loss. However, 24.9% of women did not take iron supplements despite the high prevalence of symptoms, indicating a lack of awareness of the need to treat anemia, absence of diagnoses or doctor consultations, or a misunderstanding of the significance of iron deficiency states.The results show that most respondents (63.6%) understand the importance of medical assistance in cases of heavy menstrual bleeding. However, nearly 36.4% of women did not consult a doctor despite potential health risks. This is related to insufficient awareness of the consequences of HMB (such as anemia and its complications), social or economic barriers limiting access to medical care, and underestimating the seriousness of symptoms. Among those who consulted a doctor, it is important to note that the causes of HMB are not always correctly diagnosed, nor is appropriate treatment always prescribed. This calls for improved communication between patients and doctors, as well as enhancing the quality of medical care. [6]For women who did not seek help, educational programs on the potential complications of HMB and the importance of early diagnosis should be conducted, and access to consultative services (e.g., online consultations) should be provided. Our results show that hormonal therapy was the most commonly used treatment method for women with HMB (46.9%). Oral iron supplements (18.8%) were more commonly used for treating anemia associated with significant blood loss. Surgical interventions, such as the removal of fibroids, endometrial ablation, and other surgical methods aimed at addressing the causes of bleeding, were performed in 16.2% of women. Alarmingly, 18.1% of participants did not receive any treatment despite having symptoms of HMB. This suggests a lack of accessibility to medical care or an underestimation of the seriousness of the condition.Analysis of data on iron supplement use revealed that nearly half of the respondents (49.8%) underwent long-term iron supplementation, indicating high adherence to therapy in this group. 25.3% used supplements for a short period, which may be related to insufficient anemia diagnosis, poor tolerance of supplements, or a lack of a systematic approach to treatment. 24.9% never used iron supplements, which indicates possible gaps in diagnosis and awareness among women about the need to treat iron deficiency anemia, especially in the context of HMB.Regarding contraception use, more than half of the respondents (52.9%) did not use contraception, which may be due to a lack of awareness or the perceived lack of need. Among those who use contraception, barrier methods (26.4%) and natural methods (26.1%) were the most popular. Only 48.4% discussed contraception choices with a doctor, highlighting the need to increase awareness and medical support when choosing a method of contraception. Nearly half of the respondents (50.9%) did not know about the impact of hormonal contraceptives on menstrual bleeding, which emphasizes the need for informational campaigns and consultations with specialists to raise awareness.The next part of our analysis focused on awareness of the consequences and preparation for pregnancy. 513 respondents (51.3%) planned pregnancy, emphasizing the need for quality preconception care and education on the impact of HMB, anemia, and other factors on reproductive health. 509 respondents (50.9%) were insufficiently aware of the importance of micronutrients, such as iron, in pregnancy preparation. This highlights the need for educational activities to improve women's knowledge about the impact of deficiencies on the health of the mother and the future child. 463 respondents (46.3%) had experienced miscarriages related to anemia. These data underline the importance of timely diagnosis and treatment of iron deficiency to reduce the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. A large portion of women (75.1%) reported difficulties with conception due to anemia, highlighting the significant impact of this condition on reproductive health. This emphasizes the need for anemia treatment to improve fertility. Among those planning pregnancy, 264 respondents (52%) were unaware of the risks of iron deficiency anemia. This indicates the need to raise awareness among women of reproductive age. The combination of ignorance of the risks and lack of preconception preparation in 245 respondents shows that awareness of the importance of anemia for women's health and their offspring requires active educational efforts. Only a quarter of respondents (24.4%) engage in daily exercise, while 26.3% do not engage in physical activity at all. These data highlight the need to address unhealthy habits and promote a healthy lifestyle among women. [8]It was found that women with a normal BMI who exercised 2-3 times a week more frequently had regular cycles (24-38 days) – 28 cases. Among those who did not exercise, prolonged cycles (more than 38 days) were more common – 31 cases. Among women who exercised daily, the duration of cycles was evenly distributed with no clear dominance. These data suggest that moderate physical activity (2-3 times a week) is associated with a more frequent regular cycle, while the lack of physical activity is associated with menstrual cycle irregularities.The conducted study confirmed that heavy menstrual bleeding (HMB) and related conditions, such as iron deficiency anemia (IDA), significantly impact the reproductive and overall health of women of reproductive age. The data analysis identified key aspects of the problem and outlined possible solutions. [7]

2. Conclusions

The results showed that more than half of the respondents (50.9%) were not sufficiently informed about the role of iron and micronutrients in maintaining reproductive health. This correlates with a low level of medical consultations: 36% of women with HMB symptoms did not consult a doctor. Insufficient diagnosis and untimely treatment lead to worsening IDA, which is confirmed by the high frequency of complications, such as miscarriages (46.3%). HMB in 41.9% of women is accompanied by significant iron loss, contributing to the development of IDA. Chronic anemia, in turn, is associated with miscarriages, delayed endometrial development, and reduced fertility. 75.1% of respondents reported difficulties with conception due to anemia, emphasizing the role of IDA in the pathogenesis of reproductive disorders. The lifestyle of the respondents revealed significant risk factors: lack of physical activity in 26.3% of women, regular smoking (49.2%), and alcohol consumption (33.7%). These factors may contribute to worsened hormonal balance, microcirculation in the endometrium, and an overall reduction in reproductive potential. The primary treatment for HMB among respondents was hormonal therapy (46.9%), while iron supplements were prescribed to only 18.8% of women. The lack of treatment despite the presence of symptoms was noted in 18.1% of respondents, indicating a gap between the need for treatment and its actual implementation. Awareness of preventive measures aimed at preventing HMB and IDA remains low, which requires the development of educational programs. The implementation of screening programs for women at risk of HMB and IDA, including regular monitoring of hemoglobin and ferritin levels, is essential.HMB and related conditions require a comprehensive approach, including early diagnosis, individualized treatment, and prevention. Women's awareness, access to medical care, and the implementation of educational programs play a key role in reducing morbidity and improving the quality of life for women of reproductive age.

References

| [1] | National Institute of Health and Care Excellence. Heavy menstrual bleeding: assessment and management. NICE guideline. 2018. Last updated: 24 May 2021. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng88/resources/heavy-menstrual-bleeding-assessment-and- management-pdf 1837701412549. |

| [2] | Borovkova Lyudmila Vasilievna, Volkova Svetlana Aleksandrovna, Voronina Irina Dmitrievna. The role of iron-deficiency anemia in the genesis of placental insufficiency (review). Medical Almanac, 2010. No. 4. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/rol-zhelezodefitsitnoy-anemii-v-geneze-platsentarnoy-nedostatochnosti- obzor. |

| [3] | Korotkova N.A., Prilepskaya V.N. Anemia in pregnant women. Principles of modern therapy. MS, 2015. No. XX. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/anemiya-beremennyh-printsipy-sovremennoy-terapii (Accessed: 15.03.2024). |

| [4] | Sorokina A. Anemia in pregnant women. Doctor, 2015. No. 5. URL: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/anemiya-u-beremennyh (Accessed: 16.02.2024). |

| [5] | Lancet, 2019; 393. https://www.healthdata.org/results/gbd_summaries/2019/anemia-level-1-impairment. |

| [6] | Anemia (who.int). |

| [7] | Electronic subscription of the Central Scientific Medical Library (emll.ru). |

| [8] | Dvoretsky L.I., Zaspa E.A. Iron-deficiency anemias in the practice of obstetricians-gynecologists. Russian Medical Journal. 2008; No. 29. p. 1898. [Dvoreckij LI, Zaspa EA. Zhelezodeficitnye anemii v praktike akushera-ginekologa. Russkij medicinskij zhurnal. 2008; (29): 1898. (In Russ.) |

| [9] | Johnson-Wimbley TD, Graham DY. Diagnosis and management of iron deficiency anemia in the 21st century. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2011; 4(3): 177-84. doi: 10.1177/1756283X11398736. |

| [10] | UNICEF/UNU/WHO. Iron Deficiency Anemia: Assessment, Prevention, and Control. A Guide for Programme Managers. Geneva: WHO/NHD; 2001. |

| [11] | National Institute of Health and Care Excellence. Heavy menstrual bleeding: assessment and management. NICE guideline. 2018. Last updated: 24 May 2021. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng88/resources/heavy-menstrual-bleeding-assessment-and- management-pdf 1837701412549. Accessed: 01.07.2024. |

| [12] | Munro MG. Abnormal uterine bleeding: A well-traveled path to iron deficiency and anemia. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2020; 150(3): 275-7. DOI:10.1002/ijgo.13180. |

| [13] | Da Silva Filho AL, Caetano C, Lahav A, et al. The difficult journey to treatment for women suffering from heavy menstrual bleeding: a multinational survey. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2021; 26(5): 390-8. DOI:10.1080/13625187.2021.1925881. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML