-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2025; 15(2): 275-280

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20251502.01

Received: Jan. 10, 2025; Accepted: Jan. 29, 2025; Published: Feb. 5, 2025

Features of the Clinical Course of Tuberculosis in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic

Nargiza Parpiyeva1, Dauranbek Ongarbayev2, Kazim Muxamedov3, Mavlyuda Khodjaeva3, Sabina Kayumova2

1Head of (DSc) Department of Phthisiology and Pulmonology of the Tashkent Medical Academy, Director of Republican Specialized Scientific and Practical Medical Center of Phthisiology and Pulmonology, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

2Senior Teacher, Department of Phthisiology and Pulmonology of the Tashkent Medical Academy, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

3Assistant Professor (PhD), Department of Phthisiology and Pulmonology of the Tashkent Medical Academy, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

Correspondence to: Dauranbek Ongarbayev, Senior Teacher, Department of Phthisiology and Pulmonology of the Tashkent Medical Academy, Tashkent, Uzbekistan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

In recent years, there has been a high prevalence of viral diseases (Covid-19), with damage to the pulmonary parenchyma. The pulmonary form(Sars-Cov) as an induced disease contains RNA of 80-220 nm in size [1]. The main morphological substrate of Covid-19is alveolar trauma, which in turn can lead to injuries and damage to other organs as a result of diffuse multi-organ vascular damage. In the clinic, the term viral (interstitial) pneumonia means the development of diffuse alveolar lesions. In turn, severe diffuse alveolar injury is synonymous with the clinical concept of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Viral pneumonia was rare in Uzbekistan before the pandemic and the pulmonary form of retroviruses was more common in the clinic. Based on the available data on the pathogenesis of pulmonary tuberculosis, any factor that damages the lung parenchyma increases the risk of endogenous reactivation and development of tuberculosis. The study is based on the analysis of tuberculosis patients (1156) registered in the Interdistrict Phthisiatric Dispensary No. 3 and No. 4 in Tashkent during 2018-2020.

Keywords: MDR-TB, XDR-TB, Mantoux Test (PPD-L), Diaskintest, IPD, CМCC, MBT+, MBT-, FP

Cite this paper: Nargiza Parpiyeva, Dauranbek Ongarbayev, Kazim Muxamedov, Mavlyuda Khodjaeva, Sabina Kayumova, Features of the Clinical Course of Tuberculosis in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 15 No. 2, 2025, pp. 275-280. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20251502.01.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Age, poverty, malnutrition, and comorbidities such as tuberculosis indicate an increased risk of developing more severe forms of COVID-19 [15]. Low-income populations tend to be more vulnerable to infectious diseases due to a variety of factors, including limited access to adequate healthcare and suboptimal living conditions. Furthermore, co-infection with both tuberculosis and COVID-19 poses a particular danger to these groups, for whom tuberculosis already represents a significant risk [12].The pandemic has impacted efforts to eradicate tuberculosis. As a result, the number of new tuberculosis diagnoses has decreased by 18%, while deaths from tuberculosis have increased [11]. This is believed to be a side effect of the recent lack of access to tuberculosis diagnostic and treatment resources. In the pursuit of better funding for COVID-19 eradication efforts, many countries have reduced the resources allocated to other health objectives, such as building infrastructure to combat tuberculosis [8]. In addition to the decreased focus on tuberculosis care, patients with symptoms may have been reluctant to seek medical help, leading to delays or missed diagnoses of active tuberculosis and, consequently, worsening of their condition [3]. Asymptomatic individuals with known contacts with tuberculosis patients may also avoid seeking medical care during the COVID-19 pandemic, further contributing to the decline in the diagnosis of latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) [4].In the fourth year of the pandemic, driven by new, more transmissible variants (particularly the Delta variant), COVID-19 epicenters have shifted toward low- and middle-income countries, many of which struggle to cope with a second wave of COVID-19. In 2021, South Asia and South America were particularly hard hit [2,5].Analyzing various approaches and components of addressing the tuberculosis-COVID-19 intersection, Alexandra Jaye Zimmer et al. developed the "TB Swiss Cheese Model," which has three levels: social, personal, and patient-centered healthcare. Within each level of intervention, there are gaps ("holes") that lead to negative outcomes for tuberculosis, and it is only by working at all levels simultaneously that patient protection can be achieved [6]. The model describes how COVID-19 has compromised components of certain protective layers while simultaneously creating opportunities to strengthen other layers by utilizing some technologies and resources employed in the fight against COVID-19. Tuberculosis is influenced by many health factors and can serve as a predictor, but it also acts as a factor impacting the progression of other diseases, including COVID-19 [7,16].Research conducted in South Africa has shown that both existing tuberculosis (TB) and a history of TB significantly increase the risk of mortality from COVID-19. A positive COVID-19 test is associated with a higher risk of death among individuals with rifampicin-resistant TB (61% mortality in individuals with RIF-TB and COVID-19) [2,16]. The informational component in the fight against diseases carries an extremely important message to society. COVID-19 has interrupted many informational campaigns and public initiatives. However, in response to the circumstances, certain programs have combined multi-information on both diseases. The Mercy Corps in Pakistan has helped disseminate information about TB and COVID-19 through announcements in mosques, while the COVID-19 HealthAlert by Praekelt has been providing accurate and timely COVID-19 information to the public via WhatsApp, reaching over 6 million people within the first 7 weeks of its operation. Such digital solutions, developed for COVID-19, should be repurposed for TB. As TB and COVID-19 will coexist, TB control programs and healthcare providers have a significant opportunity to use these tools for information exchange and patient-centered care [1].It is essential to facilitate and simplify the collection of biological samples for TB testing. COVID-19 has necessitated quicker and simpler testing options, leading to innovations in new types and methods of sample collection. For example, improved and accessible polyester swabs and new sampling approaches using saliva, mouthwash, oral swabs, and absorbent strips in masks have shown promise for collecting COVID-19 samples and are now being tested for TB. Easily obtainable samples that can also be used to detect other pathogens (such as SARS-CoV-2) would be revolutionary for TB [1].It is necessary to bring TB diagnostics closer to home. Currently, many tests are only available at the district level or higher, forcing patients to undergo complicated and exhausting journeys with lengthy diagnostic delays. Every country has improved access to COVID-19 testing. Decentralized testing with mobile testing sites run by healthcare workers, in pharmacies, schools, and workplaces has proven effective and well-suited even for self-collection of samples [10].The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed that most modern societies are characterized by deep disparities rooted in socio-economic opportunities, access to healthcare, political and legal power, and demographics (Theresa Ryckman). These disparities have led to socio-economic, racial, and ethnic inequalities in outcomes related to COVID-19. Such discrepancies have long been identified as fuel for TB epidemics. Unfortunately, as shown by the response to COVID-19, reliance on existing healthcare systems generally exacerbates these disparities. The authors' described approach to identifying the needs of each community regarding the quality and volume of reforms, as well as support for overcoming the impacts of COVID-19 on TB, is based on a personalized approach to assessing community needs, emphasizing human-centeredness, equity, and opportunities that consider social inequalities. The four key elements of this approach (data collection, program development, implementation, and sustainability) aim to further integrate the findings for the restructuring of healthcare systems post-COVID-19 [9].Historically, TB control programs have been organized in a top-down manner. This structure is well-suited for the implementation of biomedical achievements: more sensitive diagnostic tests, short-course preventive therapy, and new treatment drugs.Recently, the social component in the fight against TB has gained significant importance: cash assistance, food packages, legal and psychological support, and other social protection mechanisms play a crucial role. While material and technical support for the diagnostic process and access to medications are undoubtedly important, these efforts reach a point of diminishing returns. Beyond this point, social and historical factors shape the burden of disease. Socially vulnerable groups often encounter barriers to screening due to stigma, poverty, language or cultural differences, and mistrust. This cannot be resolved merely by making medications or diagnostics cheaper. To alter the trajectory of TB (and other infectious diseases), healthcare systems must be enhanced to meet the unique needs of individuals [13].In conclusion, a review of the literature suggests that national healthcare systems should acknowledge the existence of the syndemic effects of TB and COVID-19 and analyze the factors for optimal management of competing priorities. Mechanisms and programs must be developed to ensure continuity of care for socially significant diseases, particularly TB, adapted for pandemics, natural disasters, and social upheavals. Efforts should continue to implement patient-centered TB treatment, support operational research, and integrate relevant e-health programs [14].Program leaders in TB control and primary healthcare providers can act as leaders and advocates for patients, providing high-quality and sustainable TB treatment. Emphasis should be placed on the social determinants of health, the impact of the environment (e.g., education and income), the physical environment (e.g., housing and transportation), as well as access to and quality of healthcare services, including access to broadband internet. Development of multidisciplinary collaboration as a concept of One Health is essential for promoting clinical and scientific research [17].

2. State of Tuberculosis Control

- Tashkent has the 1st city center of phthisiology and pulmonology, a city clinical hospital of phthisiology and pulmonology with about 5 dispensaries. The national tuberculosis control strategy is administered by the Republican Specialized Scientific and Practical Medical Center for Phthisiology and Pulmonology. All patients are registered on the basis of diagnosis, treatment, monitoring and management recommended by WHO. Requirements of city, district and family polyclinics and hospitals, rural medical centers (RMC) are integrated with the phthisiology service. Commonly patients with symptoms characteristic of the TB process are admitted to a tuberculosis institution from the general medical network. In most cases, tuberculosis diagnosis and the final stage of treatment (maintenance stage) are carried out by the medical institution. In addition, health care institutions, Main Directorate for the Execution of Punishments of the Ministry of Internal Affairs (prisons, colonies) and the Ministry of Defense (hospitals and polyclinics for military personnel and their families) also provide specialized care to tuberculosis patients. The Ministry of Internal Affairs and the Ministry of Defense comply with both regulatory and departmental regulations when providing specialized medical care to tuberculosis patients following the Order of the Ministry of Health of the Uzbekistan Republic. Ministry of Health of the Uzbekistan Republic No. 383 dated 24.10.2014 [7].Diagnosis of tuberculosis is based on complaints of patients during a routine examination in a family polyclinic and IPD. As a rule, after the general examination, an X-ray and bacterioscopic examination should be performed. The IPD conducts an in-depth examination of tuberculosis patients carried out by a phthisiatrician according to a diagnostic algorithm: GenXpert MTB/RIF, GenXpert Ultra, HAIN Test, Mantoux test (PPD-L), diaskintest, bacterioscopic and bacteriocultural researches including drug sensitivity tests for liquid and solid media. Based on the positive result of the examination, i.e. if MBT (+) is detected in the sputum, the examined patient is sent to the city clinical hospital for treatment according to standard patterns. If there is a negative result in the sputum of the MBT ( -) or the patient refuses inpatient treatment, treatment is carried out on an outpatient basis under the supervision of the IPD, and the patient's family members undergo special diagnostic examinations and preventive measures. The result of Sensitivity / Resistance to tuberculosis using the GenXpert MTB / RIF method is sufficient to confirm the diagnosis of tuberculosis and start appropriate treatment according to the protocol [6]. Each patient diagnosed with tuberculosis is discussed and registered at the City Center for Tuberculosis and Pulmonology at the Central Medical Consultation Council (CMCC). In the IPD Each phthisiatrician is assigned a specific Family Polyclinic. They are responsible for preventing tuberculosis in the district and providing medical care to registered tuberculosis patients. In IPD the district phthisiatrician works based on the national protocol developed by the Ministry of Health of the Uzbekistan Republic.

3. Purpose of the Study

- The materials of the study were data from outpatient records of all tuberculosis patients registered in the Interdistrict Phthisiatric Dispensary No. 3 and No. 4 from 2018 to 2020. These data are provided by the Ministry of Health (previously No. 518 of 09.12.2016) according to form 8 in the Department of State Statistics of Order No. 299 of 11.12.2019. The study material included patients with tuberculosis of all ages, registered without any exceptions or criteria. Depending on the age, patients were studied separately: adults (18≤), adolescents (15-17 years) and children (≤14 years).

4. Result

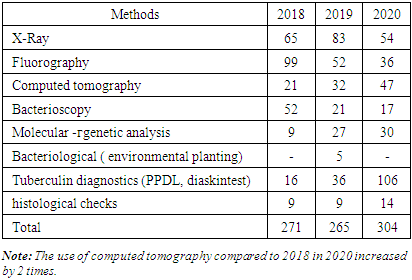

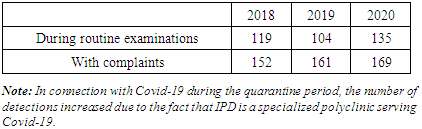

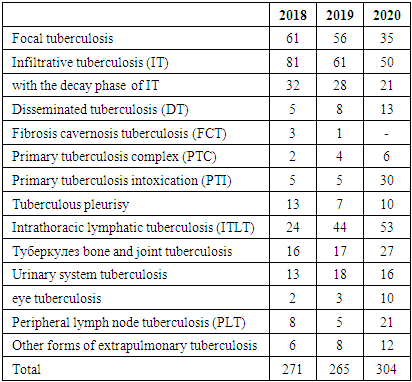

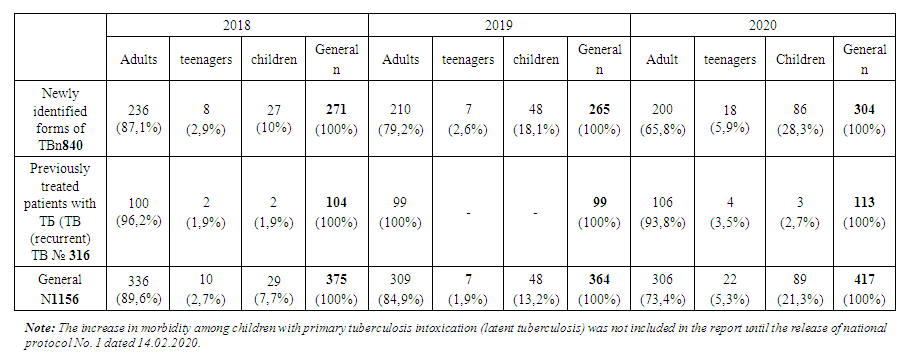

- Patients were assigned to provide specialized outpatient or inpatient care, depending on the age of patients with primary or recurrent tuberculosis, detection of the causative agent of tuberculosis (MBT+, MBT -), drug type of sensitivity or resistance (MDR, XDR). Newly diagnosed patients were assigned to a separate group. Based on the study of the age, category, and clinical form of pulmonary tuberculosis, as well as taking into account the diagnostic methods used, these patients were prescribed treatment according to the standard protocol, taking into account infection control.Over the three years, 1156 patients from the IPD were registered with tuberculosis by the decision of the CSCC [5]. Among them: 840 newly diagnosed with pulmonary tuberculosis (72.7%) and 316 recurrent (27.3%). As can be seen from Table 1, adults accounted for 951 (82.3%), adolescents 39 (3.4%), and children 166 (14.3%) by age.

| Table 1. Changes in the incidence of tuberculosis by year |

|

|

|

5. Conclusions

- 1. Over the years, the population in the IPD service area has increased by 0.093 million people, while the overall incidence of tuberculosis has decreased by 11,5%0, and the rate of tuberculosis relapses has decreased by 1%, but the incidence has increased by 4%.2. According to statistics, the morbidity rate is expected to increase 3-fold among children in 2018-30,1%0, and in 2020-90,5%0. This figure among adolescents in 2018 is 45,9%0, and in 2020-259%0, i.e., there is a 5,6 -foldа increase in morbidity among adolescents. The tendency to increase morbidity among young people indicates a good organization of preventive examinations of the population, sanitary and educational work of diagnostics and immunodiagnostics, as well as detection of the disease at an early stage. Using modern innovative diagnostic methods.3. Due to the increase in the incidence of adults, the incidence of children and adolescents who came into contact with them has increased.4. Among diagnostic methods, the effectiveness of computed tomography and tuberculin diagnostics methods was high and allowed detecting twice more diseases. As a result of these studies, we can show that during the Covid pandemic the necessity for CT scans due to coronavirus infection in most patients made it possible to detect the incidence of tuberculosis along with various other diseases.5. There was a more frequent treatment in medical institutions of primary identified patients. 80% of patients received intensive medical treatment for tuberculosis in a hospital setting.6. The rate of treatment of patients with drug-resistant tuberculosis in outpatient settings during intensive care has become 0.1% due to the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020.7. It should be noted that the clinical forms of PTI, DT, ITLNTB increased. Disseminated tuberculosis + Covid-19 was more common during the pandemic among patients at initial detection. The reduction of destructive, advanced forms of lung TB is due to the widespread use of the above-mentioned modern diagnostic methods, which, in turn, leads to early detection and detection of the tuberculosis process.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML