-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2025; 15(1): 269-273

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20251501.53

Received: Jan. 5, 2025; Accepted: Jan. 28, 2025; Published: Feb. 3, 2025

Surgical Treatment of Tethered Cord Syndrome in Children with Spinal Dysraphism

Yugay I. A.

Republican Specialized Scientific and Practical Medical Center of Neurosurgery, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

Correspondence to: Yugay I. A., Republican Specialized Scientific and Practical Medical Center of Neurosurgery, Tashkent, Uzbekistan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

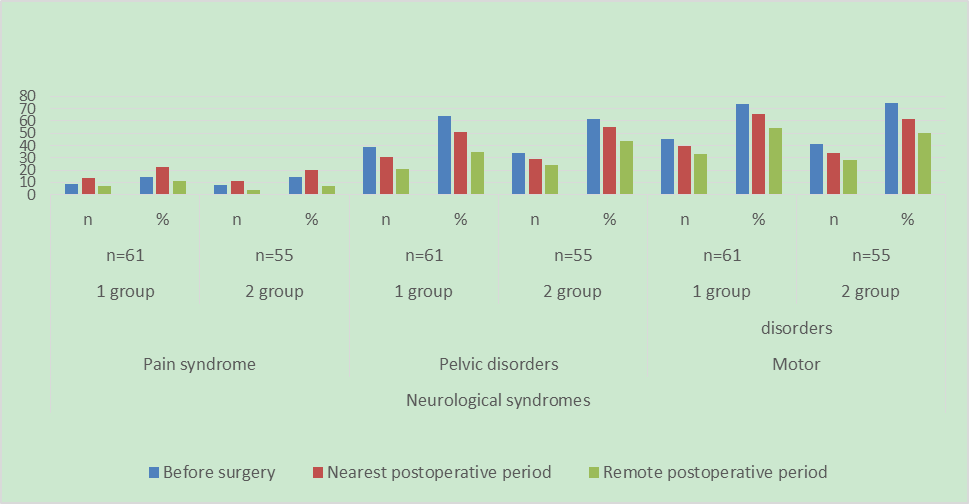

The results of surgical treatment of children who underwent surgery for fixed spinal cord syndrome were analyzed. The features of the surgical technique for eliminating fixation of the spinal cord in closed dysraphism were determined, which made it possible to improve the results of treatment. In total, from 2019 to 2024, 61 children were operated on for a fixed spinal cord. Of these, in 52 (85.2%) patients, fixation of the terminal filament was combined with lipomeningocele, diastematomyelia, or myelomeningocele. All patients underwent a detailed study with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography MSCT, performed electroneuromyography (ENMG), as well as tractography. In all these patients, the release of the stretched spinal cord and roots, as well as the dissection of the arachnoid and fibrous cords, was performed surgically using intraoperative monitoring and microscopic techniques. The results of the study were compared with a retrospective control group of patients, consisting of 55 patients. At the same time, it was found that the approach used by us significantly improved the condition in the long-term period according to electroneuromyography and neurological deficit in 29.5% of patients with pelvic disorders and in 19.6% of patients with motor disorders of the main group.

Keywords: Spina bifida, Tethered cord syndrome, Lipomeningocele, Diastematomyelia

Cite this paper: Yugay I. A., Surgical Treatment of Tethered Cord Syndrome in Children with Spinal Dysraphism, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 15 No. 1, 2025, pp. 269-273. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20251501.53.

1. Introduction

- Tethered cord syndrome (TCS) occurs as a result of fixation of the spinal cord in the spinal canal due to structures of congenital origin. Primary TCS is observed in patients with intradural lipomas, lipomyelomeningocele, malformations of the split spinal cord - dystematomyelia, dermal sinus and neuroenteric cysts, thickened and shortened terminal filament [4,7,8,11]. TCS leads to mechanical torsion and ischemia in the distal parts of the spinal cord, including the conus medulla, therefore, in TCS, motor-sensory disorders in the lower extremities and urological complications are mainly observed.The study of TCS began at the end of the 19th century by scientists from different countries. Virchow first used the term "hidden spina bifida" to describe skin-covered lesions and the term "horse-maned woman" for hypertrichosis in 1875. Jones of Great Britain was the surgeon who first successfully released a spinal cord fixation in 1891. Fuchs used the term "myelodysplasia" for the clinical picture, consisting of deep tendon reflex-sensitive disorders, enuresis, and foot deformities in patients with dystematomyelia. Yamada and co-authors reported that various neurological manifestations in TCS are the result of ischemia of the caudal spinal cord due to its mechanical stress [2,3,9,10,13].Since TCS results from increased caudal tension on the spinal cord, the primary treatment for lesions and structures involving arachnoid cords, primitive neural placodes, thick or fibrofatty terminal filament, lipomyelomeningocele, diastomatemyelia, and fixation-released intradural lipomas is surgical [1,5,6,11,12].The purpose of the study. To analyze the results of surgical treatment of children who underwent surgery for TCS. To determine the features of the surgical technique for eliminating fixation of the spinal cord in closed dysraphism.

2. Material and Methods

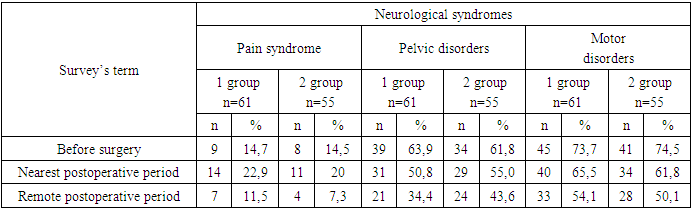

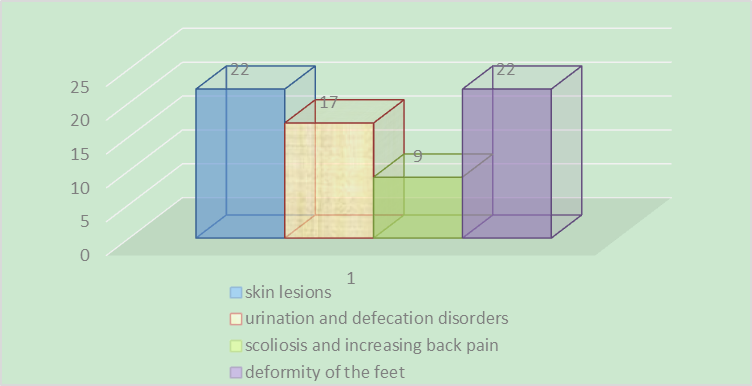

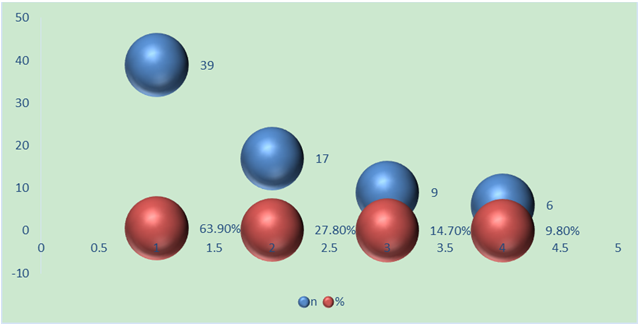

- Surgical treatment of our studied main group for spinal cord release was carried out in 61 children with TCS for 5 years. 32 (52.4%) patients were girls and 29 (47.5%) boys. The median age was 53.67 months (30 days to 11 years). Symptoms were skin lesions in 22 patients (36.06%), urination and defecation disorders in 17 patients (27.8%), weakness in the legs or feet, numbness and/or spasticity or progressive deformity of the feet in 22 patients (36%), scoliosis and increasing back pain in 9 patients.

| Diagram 1. Clinical manifestation of fixed spinal cord |

| Diagram 2. Nosological forms of fixed spinal cord |

3. Results and Discussions

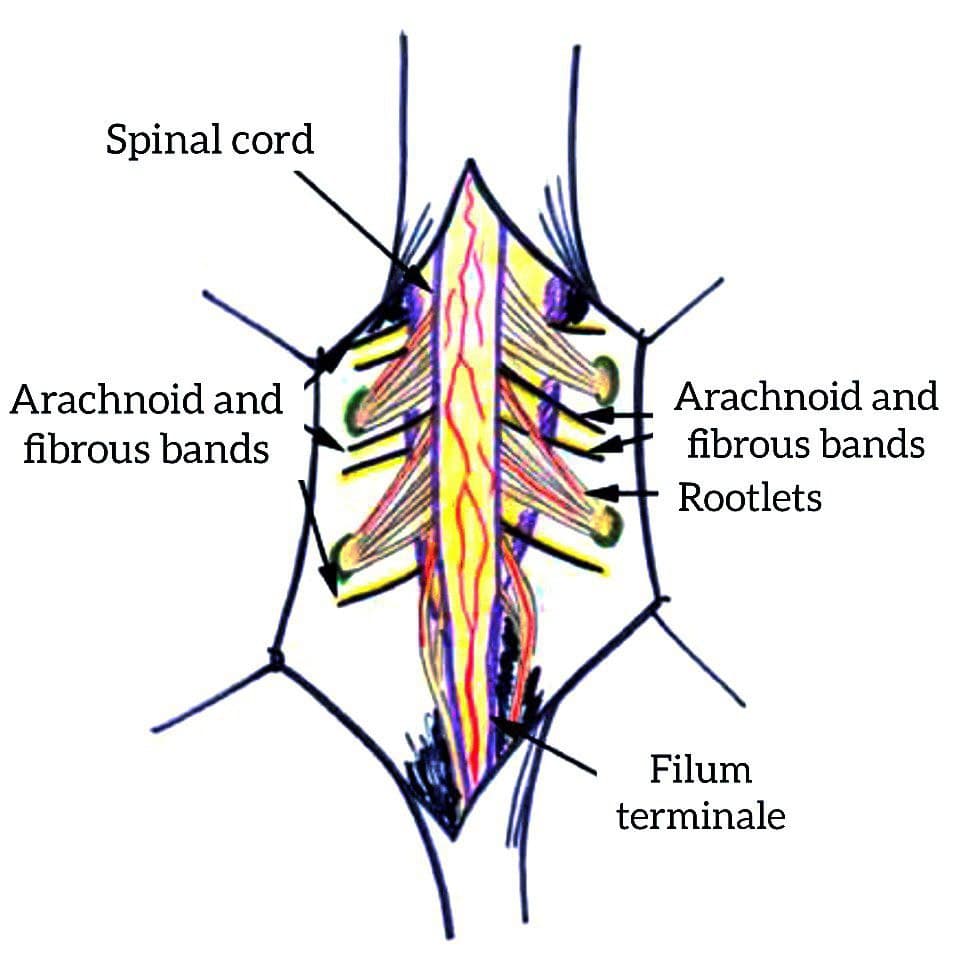

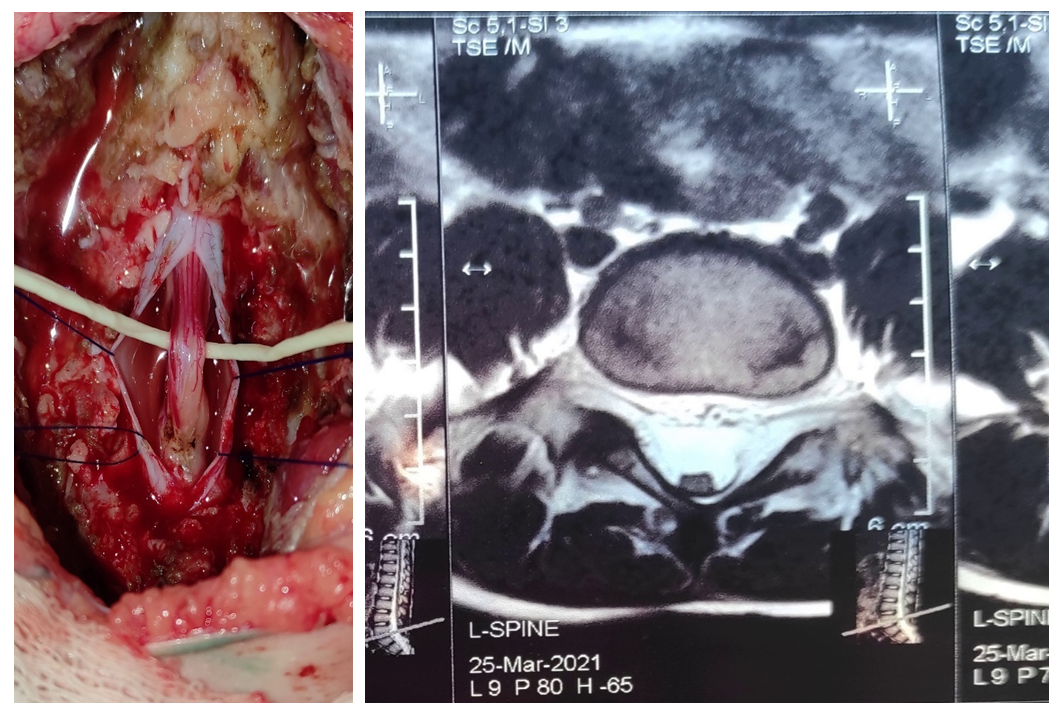

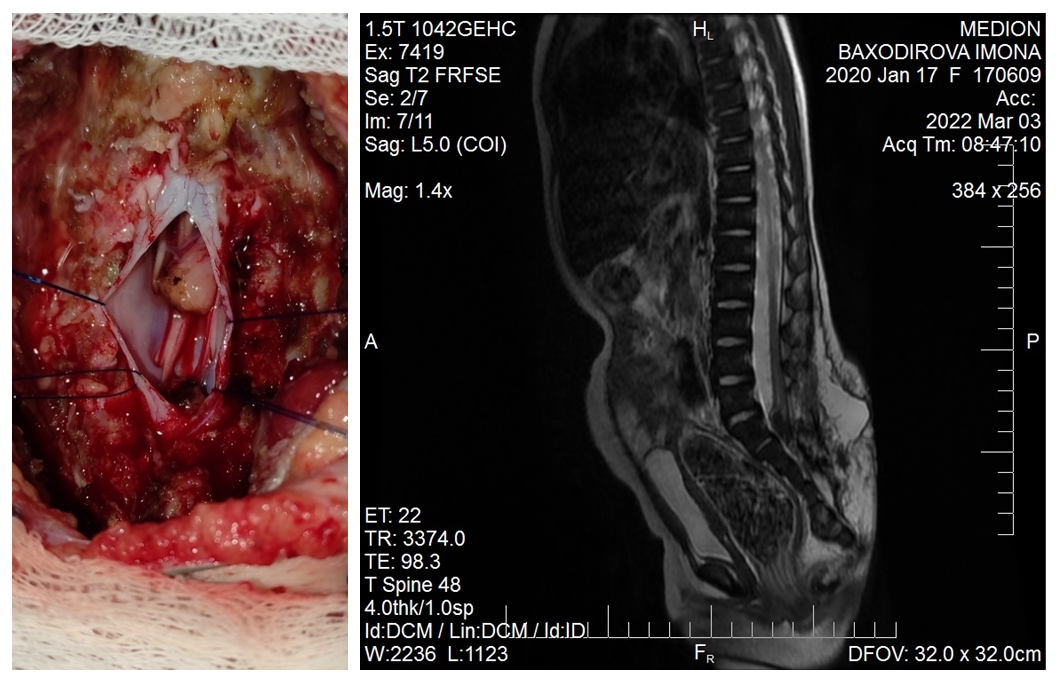

- In total, from 2019 to 2024, 61 children were operated on for a fixed spinal cord. Of these, in 52 (85.2%) patients, fixation of the terminal filament was combined with lipomeningocele, diastematomyelia, or myelomeningocele. Fixed spinal cord surgery with these malformations has shown some variation, and the technique varies depending on the underlying lesion. Not only the cutting of the terminal thread, but also the cutting and cleaning of the arachnoid cords around the roots are important for effective defixation.Features of surgical technique and conditions for the operation. The position of patients on the abdomen, with the installation of electrodes for intraoperative neuromonitoring (computer complex for neuromonitoring INOMED). The operation takes place under general anesthesia, with microscopic assistance.The standard procedure is a laminectomy, depending on the level and extent of the anomaly, to expose the dura mater and then identify the terminal filament of the spinal cord. In the case of lipocele, additional opening and excision of the lipoma. In cases of hidden spina bifida, laminectomy at the level of the bony septum. If the spinal cord, due to fixation, continues to levels S1 or S2, giving rise to several sacral roots, laminectomy was performed down to that level. The dura mater was opened by us along the midline and secured with four sutures on both sides. After opening the dura mater, the terminal filament, arachnoid cords and roots were identified.After opening the dura mater, we used a microscope and a set of microinstruments. The terminal thread appeared to us as a fibrovascular cord containing a large vessel, which becomes smaller along the distal path. The thickness of the terminal filament varied over a wide range - from 2 mm to 1 cm.The most important issue is the differentiation of nerve elements from adhesions and fibrous bands and terminal thread. Only using external signs it is very easy to confuse roots and spider webs. The roots at the sacral level are bidirectional and can be identified by their size and position. The arachnoid bands are usually attached to the dura mater and roots (Figure 1).

| Figure 1. The line drawing shows spinal cord, filum terminale, rootlets and arachnoid and fibrous bands which are attached and tethered the spinal cord |

| Figure 2. Thickened terminal thread. Posteriorly closely adjacent to the dura mater |

| Figure 3. Transection of the terminal filament after careful coagulation |

|

| Diagram 3. Comparative evalution of the results of surgical treatment |

4. Conclusions

- Thus, based on the results of our approaches to improving the surgical technique for eliminating the syndrome of a fixed spinal cord in closed dysraphism, we can draw the following conclusions:1. Surgical intervention is necessary in children of the early age group, immediately after the anomaly is detected.2. Full-scale surgical intervention is possible only with the use of intraoperative neurophysiological control and microsurgical techniques.3. Defixation should concern not only the terminal thread, but also arachnoid and fibrous adhesions. It is necessary to carry out plastic surgery of the dura mater sufficient for the free passage of CSF.4. The approach we used improved significantly the condition in the long-term period according to electroneuromyography and neurological deficit in 29.5% of patients with pelvic disorders and in 19.6% of patients in the main group with motor disorders.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML