-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2025; 15(1): 201-206

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20251501.39

Received: Dec. 20, 2024; Accepted: Jan. 13, 2025; Published: Jan. 27, 2025

Surgical Treatment of Degenerative Lumbar Spinal Stenosis Using Endoscopic Decompression

Shatursunov Shakhaydar Shaaliyevich1, Eshkulov Dostonjon Ilkhomovich2, Khujanazarov Ilkhom Eshkulovich3

1DSc, Professor, Republican Specialized Scientific and Practical Medical Center of Traumatology and Orthopedics of Uzbekistan, Director, Uzbekistan

2Republican Specialized Scientific and Practical Medical Center of Traumatology and Orthopedics of Uzbekistan, Traumatology and Orthopedics Doctor, Uzbekistan

3DSc, Republican Specialized Scientific and Practical Medical Center of Traumatology and Orthopedics of Uzbekistan, Head of Rehabilitation Department, Traumatology and Orthopedics Doctor, Head of traumatology and Orthopedics Department Tashkent Medical Academy, Uzbekistan

Correspondence to: Eshkulov Dostonjon Ilkhomovich, Republican Specialized Scientific and Practical Medical Center of Traumatology and Orthopedics of Uzbekistan, Traumatology and Orthopedics Doctor, Uzbekistan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Objective: The results of percutaneous endoscopic and microsurgical decompression are compared. It was found that the time of surgery, significant bed-days and the period of disability were associated with the group of endoscopic decompression. Purpose: to study the effectiveness of endoscopic decompression in patients with degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis. Materials and methods of the research: the article is about the effectiveness of using endoscopic decompression in 120 patients who were treated as outpatients and inpatients in the Vertebrology Department of the RSSPMCTO clinic during the year 2020-2024, 56 of the patients were male and 64 were female, and the average age was 63.8±7.6. Patients were divided into 2 groups: main (62) and control (58). The main group of patients received endoscopic decompression that the control group received. The effectiveness of the treatment was evaluated on the basis All patients underwent a comprehensive neurological and instrumental examination, including traditional and functional radiography of the lumbosacral spine, MSCT (CT) and MRI, as well as electroneuromyography (ENMG). Results: in both groups of patients, after operative treatment, it was found that pain decreased and clinical benefit increased. All main group patients had better results compared to the control group according to VASh, ODI, McNub scales. During the post-treatment MRI and CT examination, it was found that the neurological sign has improved and the back pain has decreased. Conclusion: Based on the study, we can say that the efficiency of endoscopic discectomy is comparable to the microsurgical technique. Considering that this method is comparable to endoscopic decompression in terms of its technical characteristics and capabilities, this technology can be used to remove herniated intervertebral discs. In some cases, the technical capabilities of the method allow decompression of nerve structures, which can be used in the treatment of non-discogenic spinal canal stenoses.

Keywords: PSLD (Percutaneous Stenoscopic Lumbar Decompression), Spinal canal stenosis, Degenerative stenosis, Decompression, Endoscopy, Over-the-top decompression

Cite this paper: Shatursunov Shakhaydar Shaaliyevich, Eshkulov Dostonjon Ilkhomovich, Khujanazarov Ilkhom Eshkulovich, Surgical Treatment of Degenerative Lumbar Spinal Stenosis Using Endoscopic Decompression, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 15 No. 1, 2025, pp. 201-206. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20251501.39.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- According to modern literary sources, about 80% of people during their lives suffered at least one episode of low back pain with or without pain in the lower extremities [8,10]. Up to 70% of people at least once in their lives experienced such back pain that made them turn to a neurologist, and 19% of those who applied were forced to resort to surgery due to the lack of a tangible effect from conservative therapy [9,10]. In 5–10% of patients, low back pain is caused by herniated intervertebral discs and is accompanied by radiculopathy and sciatica in 43% of cases [9]. The number of patients with a herniated disc is increasing all over the world, including at the expense of young people. Currently, one of the most effective and at the same time relatively safe methods of treatment of intervertebral hernia of the lumbosacral spine is its endoscopic removal [8,11].There are several stages in the evolution of endoscopic technologies in medicine, each of which is characterized by the improvement of equipment and the emergence of new diagnostic and treatment methods: fiber optic (1958–1981), digital (1981–2003) and the modern stage of telemedicine technologies. Leaving aside the first attempts at intravital endoscopy of the epidural and subarachnoid spaces of the human spinal cord, undertaken by Pool in 1937, the beginning of the introduction of endoscopic methods of treating spinal diseases into clinical practice should be considered the 80s. XX century., attributable to the digital period of endoscopy. By that time, modern models of rigid and flexible endoscopes had already been designed, and they were tested in various fields of surgery. Thanks to this, a high level of diagnostic and therapeutic endoscopic interventions on the spine was achieved by the efforts of neurosurgeons and orthopedists in a relatively short time interval.Percutaneous video endoscopic spine surgery currently includes operations performed from percutaneous access under the control of radiation and video endoscopic imaging methods, using rigid multichannel endoscopes and special instruments. Such a combination of interventional and video endoscopic technologies in spinal surgery is referred to in the English-language literature as a full-endoscopy method (literally - “completely endoscopic”). In the 1990s, a technique was developed that made it possible to use endoscopic discectomy and endoscopic posterior interbody fusion; An original port for interlaminar access was developed and introduced into clinical practice. At the same time, the principles of endoscopic decompression were developed for the treatment of degenerative spinal stenosis [13]. Thus, endoscopic methods for removing intervertebral hernias using the interlaminar PSLD (Percutaneous Stenoscopic Lumbar Decompression) method have been introduced into surgical practice. PSLD has the features and benefits of minimally invasive treatment, including a small incision, little blood loss, atraumaticity, and, as a result, early rehabilitation. PSLD does not disrupt the structure of the spinal canal, does not affect the stability of the spine, and does not lead to significant postoperative fibrosis in the spinal canal [1,2,3]. The popularization of this technique has accelerated technical progress in this field of medicine. The possibilities of percutaneous endoscopic surgery have increased significantly [5,6,7]. Access to the spinal canal is no longer absolutely dependent on the presence of interosseous spaces of the spine and their size. In terms of the surgical accessibility of herniated intervertebral discs, percutaneous endoscopy with all the approaches and techniques available to the neurosurgeon is not inferior to standard decompression. Despite the prevalence of the technique, it remains unclear to this day whether endoscopic decompression will become the new standard of surgical treatment for discogenic lumboischialgia, while displacing lumbar decompression. In terms of the surgical accessibility of herniated intervertebral discs, percutaneous endoscopy with all the approaches and techniques available to the neurosurgeon is not inferior to standard decompression. Despite the prevalence of the technique, it remains unclear to this day whether endoscopic decompression will become the new standard of surgical treatment for discogenic lumboischialgia, while displacing lumbar decompression. The final answer to this question will probably be obtained in the course of randomized controlled trials of clinical efficacy, taking into account all options for the use of intracanal endoscopic approaches and techniques. In connection with the above, there is a need for further comparative prospective studies of decompression (MD) and endoscopic decompression (ED), which was undertaken in this work.The final answer- to this question will probably be obtained in the course of randomized controlled trials of clinical efficacy, taking into account all options for the use of intracanal endoscopic approaches and techniques. In connection with the above, there is a need for further comparative prospective studies of decompression (MD) and endoscopic decompression (ED), which was undertaken in this work.The purpose of the study: to study the effectiveness of endoscopic decompression in patients with surgical treatment of degenerative lumbar spinal stenosis using endoscopic decompression.

2. Research Materials and Methods

- Materials on patients were obtained from 120 patients who were treated as outpatients and inpatients during 2020-2024 in the Department of Vertebrology of the Republican Specialized Scientific And Practical Medical Center Of Traumatology And Orthopedics (RSSPMCTO) clinic. 56 of the patients were male and 64 were female, and the average age was 63.8±7.6. Patients were divided into 2 groups: main (62) and control (58). Among them, 62.8% of patients neurogenic intermittent claudication, 14% had radicular pain, 23.2% had back pain.Surgery was indicated if the conservative treatment had proved ineffective. The details of this study were explained to the patients, and all patients provided informed consent. Demographic and preoperative data, including medical history, BMI, comorbidities, and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score, were documented. To simplify the presentation of medical history, we classified patients’ comorbidities into several categories: cardiac, gastrointestinal, renal, pulmonary, and multiple comorbidity. Surgical data included the number of operated level, procedure time, and bleeding. Clinical outcomes included length of hospitalization, postsurgical complications, and revision surgery rate. The preoperative and postoperative cross-sectional area of the lumbar spinal canal was calculated from computed tomography (CT).Flexion-extension lumbar radiographs were obtained again at 6 and 12 months postoperatively, and spinal instability was defined as a sagittal plane translation of ≥5mm on flexion-extension radiographs (Radiological evaluation was judged by two observers). Postoperative follow-up consisted of the visual analog scale (VAS), Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) questionnaire, and 36-Item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36) at 6 and 12 months. Patient-reported outcomes were collected via face-to-face assessment or telephone interviews. “Over the Top” Technique. The endoscopic decompression procedure has been previously described [7,8]. In brief, we made a 3-5cm midline incision after fluoroscopic confirmation of the surgical level. After skin incision, the multifidus muscle was dissected unilaterally from the spinous process and lamina using a Cobb elevator and retracted by a Taylor retractor. After detachment of paraspinal muscles, ipsilateral laminotomy was performed using a burr and Kerrison punches, followed by flavectomy using a microscope. To view the contralateral side, the operation table and microscope were tilted approximately 15 to 25°. For decompression, undercutting of the spinous process and contralateral lamina was performed using a burr and Kerrison punches, followed by flavectomy. After contralateral laminotomy and flavectomy, complete neural decompression was confirmed by the restoration of dural pulsation.

3. Research Results

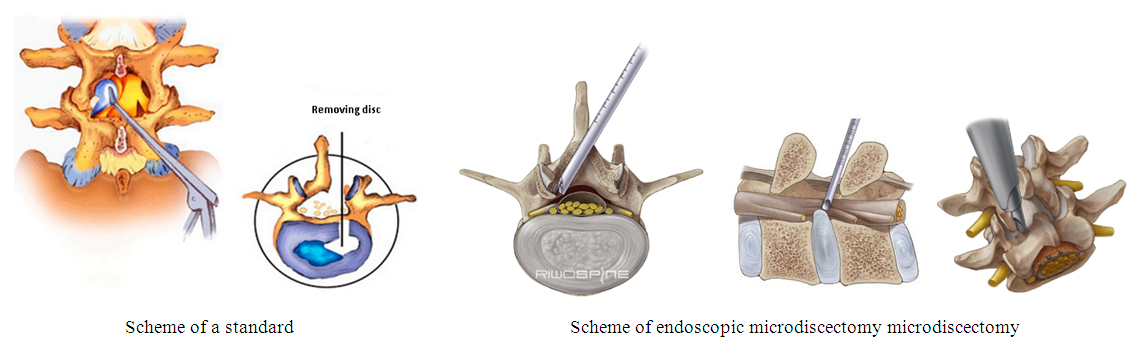

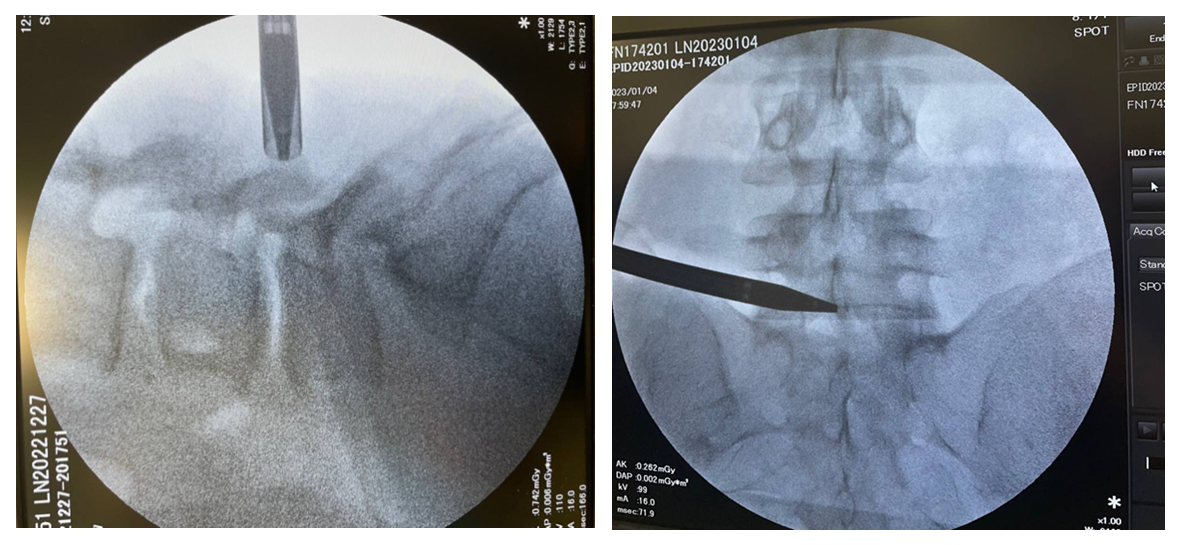

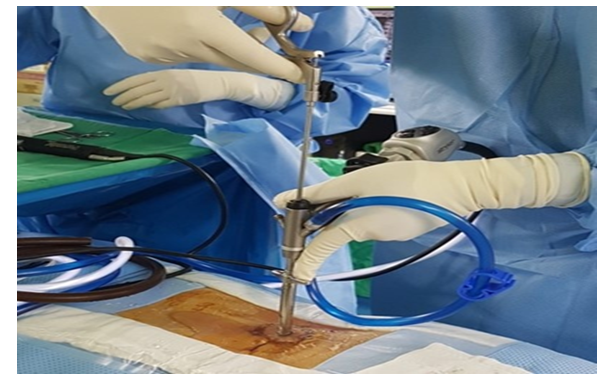

- After receiving appropriate conservative treatment for at least 2–3 months, surgery is recommended when patients complain of pain, muscle weakness, and gait disturbance caused by lower-extremity paresthesia, which affect their daily life. Surgery is rarely used to treat low back pain caused by spondylolisthesis and scoliosis when there is no instability [18]. It is difficult to predict the likelihood of recovery after surgery, even when uncommon long-term motor paralysis is the main symptom; thus, other causes should be identified prior to surgery. Rapidly developing neurological abnormalities or the lack of urine and feces necessitate early decompression [11,21]. When deciding whether to undergo surgery, abnormal findings on CT or MRI imaging should correlate to the patient’s complaints [22]. The principle of surgical treatment is to sufficiently decompress the nervous structures [11]. If instability due to the removal of too many bone structures following adequate decompression is anticipated, immobilization should be considered. Candidates for fusion surgery may also include those who have severe stenotic lesions and spondylolisthesis, scoliosis, or kyphosis [19].Other fusion requirements include disk herniation following prior surgery, recurring stricture, and proximal segmental degeneration caused by prior fusion. In older individuals with severe multisegmental stenosis, laminectomy alone may be recommended (Figs. 1–3) [3]. Less than 50% of the inner section of each facet of one spinal segment must be removed during decompression to provide appropriate decompression without resulting in segmental instability [3]. More localized decompression is possible by identifying the exact cause of symptoms with selective nerve root blocks. Checking for neural membrane adhesions, which may be present even in the absence of a history of surgery, during decompression can help limit the risk of dural damage [20].

| Figure 1. Standart and endoscopic decompression |

| Figure 2. Controlling endoscope via EOC |

| Figure 3. Endoscopic approach to the lumbar spine stenosis |

4. Summary

- The neurological status of patients before surgery varied according to the intensity of the radicular pain syndrome and the duration of the disease. Immediately after the operation, the majority of patients experienced a complete regression of radicular pain syndrome, and all patients were subjected to the same activity restrictions - restriction of axial loads and strictly mandatory wearing of an orthopedic lumbar corset for 1 month after the intervention. Of the 92 patients in the endoscopic group, 5 (5.4%) had a relapse, which required a second operation. In 4 (3.4%) patients, prolonged pain was observed within 1 month after discharge, which corresponded to an unsatisfactory result on the Macnub scale. In 7 (7.6%) patients, short-term pain of a pulling nature was observed for no more than 1 week after surgery. Another 6 (6.5%) patients had short-term sensations, qualified by patients as aching pain in the same dermatome as before the operation, but regressed on the 1st–2nd day after the operation. The remaining patients noted the complete disappearance of all symptoms and returned to normal life soon after discharge. Thus, the efficiency of the endoscopic method was 88.2%.

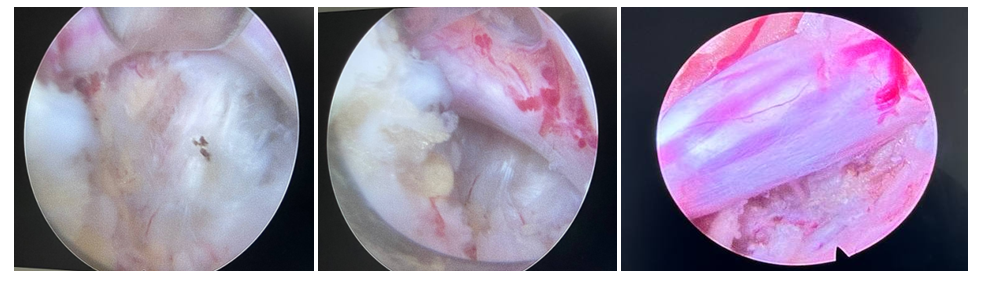

| Figure 4. Intraoperative view of spinal nerves |

5. Conclusions

- Based on the study, we can say that the efficiency of endoscopic discectomy is comparable to the microsurgical technique. Considering that this method is comparable to microdiscectomy in terms of its technical characteristics and capabilities, this technology can be used to remove herniated intervertebral discs. In some cases, the technical capabilities of the method allow decompression of nerve structures, which can be used in the treatment of non-discogenic spinal canal stenoses.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML