Rozikova Dildora Kodirovna

Bukhara State Medical Institute, Bukhara, Uzbekistan

Correspondence to: Rozikova Dildora Kodirovna, Bukhara State Medical Institute, Bukhara, Uzbekistan.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Abstract

Vaginal microbiota plays a key role in ensuring women's reproductive health. Disturbances in its composition (dysbiosis) are associated with an increased risk of reproductive losses, such as infertility, premature birth, and miscarriage. This paper presents the results of vaginal microbiota analysis in pregnant women, including indicators of normal and pathogenic flora in groups with different levels of risk of reproductive losses. The study showed that a decrease in the number of lactobacilli and an increase in opportunistic microorganisms increases the likelihood of dysbiosis, which, in turn, contributes to the development of pregnancy complications. The data obtained emphasize the importance of monitoring the vaginal microbiocenosis for predicting and preventing reproductive losses.

Keywords:

Vaginal microbiota, Dysbiosis, Lactobacilli, Reproductive losses, Pregnancy, Microbiome, Infectious complications, Prognosis

Cite this paper: Rozikova Dildora Kodirovna, Vaginal Microbiota Analysis Results in Predicting Reproductive Losses, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 15 No. 1, 2025, pp. 184-187. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20251501.35.

1. Introduction

Vaginal microbiota is a key factor in ensuring women's reproductive health. It includes a wide range of microorganisms, including bacteria of the genus Lactobacillus, which help maintain an acidic environment and suppress the growth of pathogenic microorganisms. Imbalance in the microbiocenosis, known as dysbiosis, can lead to a number of pathological conditions, including infertility, premature birth, miscarriage, and postnatal complications [1].Modern microbiota research methods, such as next-generation sequencing and metagenomic analysis, allow detailed study of the composition and functions of the microbiome, as well as their relationship with reproductive health. These methods open up new opportunities for the development of personalized approaches to treatment and prevention [2].The constant presence of lactobacilli in the vaginal environment plays an important role in maintaining the barrier functions of the epithelium and preventing colonization by pathogenic microorganisms. Their reduction is associated with an increased risk of bacterial vaginosis, pelvic inflammatory diseases, and sexually transmitted infections. Studies also confirm that changes in the vaginal microbiome may be associated with the risk of premature birth and miscarriage [3,4].In addition to endogenous factors such as hormonal changes and immune status, the state of the vaginal microbiota is also affected by exogenous factors. These include stress, diet, use of antibiotics and other medications, and lifestyle. For example, increased sugar consumption and lack of probiotic products in the diet can contribute to the development of dysbiosis [5].Particular attention is paid to the relationship between vaginal microbiota and systemic processes in the body. Microbiocenosis disorders can provoke inflammatory reactions leading to deterioration of the endometrium, which in turn affects the process of embryo implantation and the successful course of pregnancy. In addition, studying the role of microbiota in the formation of the mother's immune response allows us to better understand the mechanisms for preventing infectious complications [6].Thus, the study of vaginal microbiota is of great importance for the prediction, diagnosis and prevention of reproductive losses. Further in-depth study of this topic contributes to the development of new therapeutic strategies aimed at maintaining a healthy microbiocenosis and reducing the risk of pregnancy complications.The aim of the article is to analyze the state of the vaginal microbiota and study its role in predicting the risk of reproductive loss.

2. Material and Methods

The design of the study is determined by the purpose of the work and the objectives. A total of 146 pregnant women of reproductive age with complicated obstetric and gynecological anamnesis, as well as with the risk of reproductive losses, were prospectively examined. According to the inclusion/exclusion criteria, pregnant women were selected, from which 3 groups were formed at a period of up to 10 weeks of pregnancy: the main one (n=65) - group 1 (with the risk of developing embryochorial insufficiency) and group 2 - 61 pregnant women with retrochorial hematoma with a gestation period of up to 10 weeks; control (n=20) - group 3 - conditionally healthy pregnant women up to 10 weeks.

3. Results of the Study

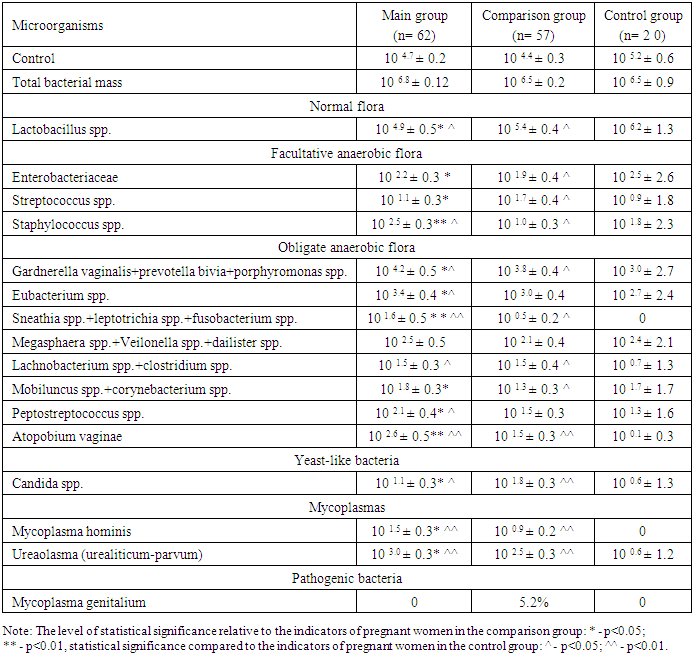

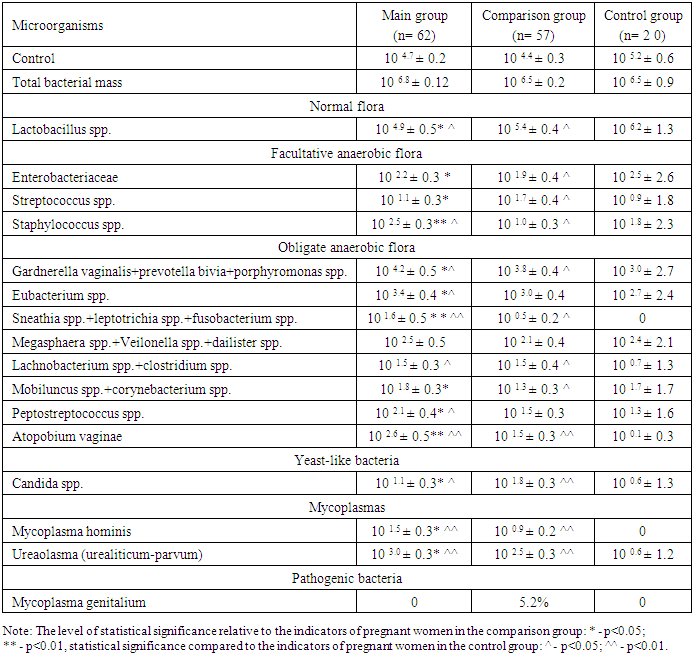

At the next stage of the study, a vaginal sample was taken and bacteriological analysis was performed. Pregnant women from all three groups were involved in the study. Bacterial analysis was performed by identifying normal flora, facultative anaerobic flora, obligate anaerobic flora, yeast-like bacteria and mycoplasma. The results of the analysis are presented in Table 1.Table 1. Results of vaginal microbiota analysis, M±m

|

| |

|

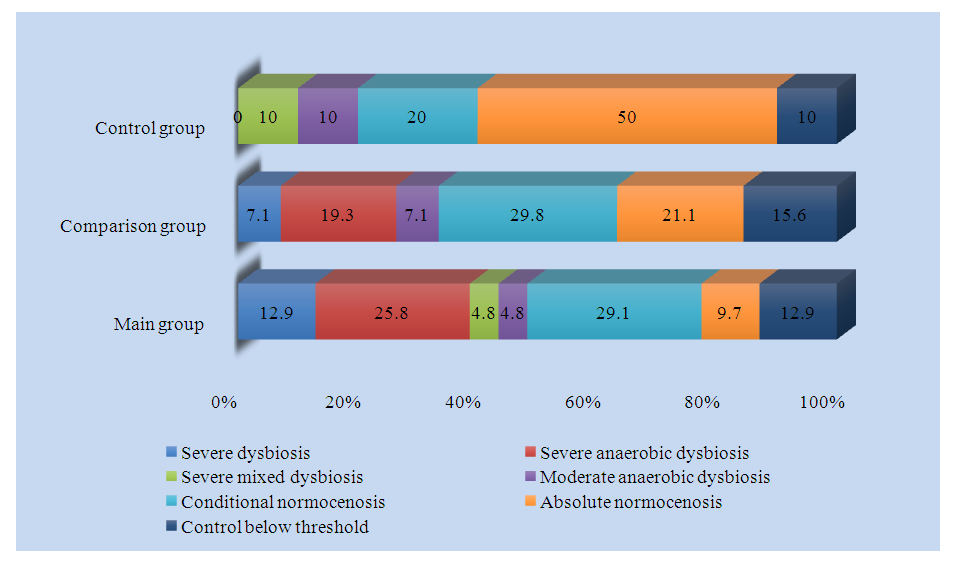

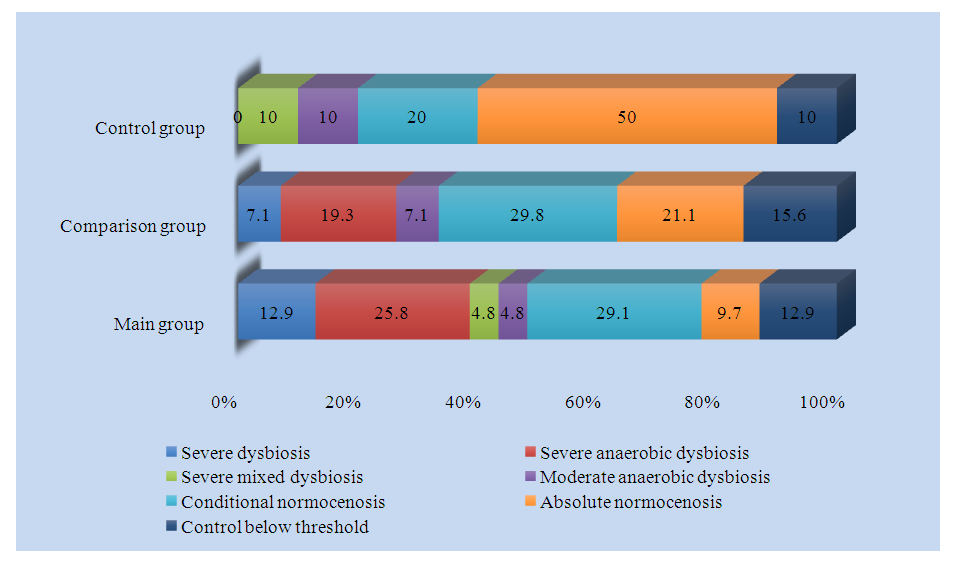

Analysis of vaginal microflora showed that the control and total bacterial mass demonstrated similar results in the main, comparative and control groups (10 4.7 ±0.2, 10 4.4 ±0.3, 10 5.2 ±0.6 and 10 6.8 ±0.12, 10 6.5 ±0.2, 10 6.5 ±0.9, p>0.05, respectively).Lactobacillus spp., which is normal flora, was 104.9±0.5 in the main group, 105.4 ± 0.4 in the comparison group and 106.2 ± 1.3 in the control group (p<0.05). A decrease in the number of lactobacilli, which are considered beneficial, creates conditions for the proliferation of opportunistic and pathogenic bacteria.Enterobacteriaceae, which are facultative anaerobic flora, amounted to 10 2.2 ± 0.3, 10 1.9 ± 0.4 and 10 2.5 ± 2.6, respectively, in the main, comparative and control groups (p < 0.05), and among streptococci - Streptococcus spp. 10 1.1 ± 0.3, 10 1.7 ± 0.4 and 10 0.9 ± 1.8, respectively (p < 0.05). Of staphylococci - Staphylococcus spp. amounted to 10 2.5 ± 0.3 in the main group, 10 1.0 ± 0.3 in the comparison group and 10 1.8 ± 2.3 in the control group.When analyzing the obligate anaerobic flora, the Gardnerella vaginalis+prevotella bivia+porphyromonas values were higher in pregnant women of the main group compared to the comparison and control groups (10 4.2 ±0.5, 10 4.2 ±0.5 and 10 3.0 ±2.7, p<0.05, respectively). Similar results were shown by Eubacterium spp. (10 3.4 ±0.4, 10 3.0 ±0.4 and 10 2.7 ±2.4, p<0.05, respectively). Sneathia spp.+leptotrichia spp.+fusobacterium spp. was detected only in the main and comparative groups and was not registered in the control group, and in pregnant women of the main group it was reliably higher than in the comparison group (10 1.6 ±0.5 and 10 0.5 ±0.2, p<0.05, p<0.01, respectively). Megasphaera spp.+Veilonella spp.+dailister spp. showed similar results in all three groups, between which no reliable difference was found (p>0.05). The number of Lachnobacterium spp.+clostridium spp., also belonging to the group of obligate anaerobic bacteria, was reliably lower in pregnant women of the control group compared to the main and comparison groups and amounted to 10 1.5 ±0.3, 10 1.5 ±0.4 and 10 0.7 ±1.3, respectively (p<0.05). The number of Mobiluncus spp.+corynebacterium spp. was significantly reduced in pregnant women of the comparison group compared to pregnant women of the main and control groups (10 1.8 ±0.3, 10 1.7 ±1.7 and 10 1.3 ±0.3, p<0.05, respectively). Peptostreptococcus spp. and Atopobium vaginae were 10 2.1 ±0.4 and 10 2.6 ±0.5, respectively, in the main group, 10 1.5 ±0.3 and 10 1.5 ±0.3, respectively, in the comparison group and 10 1.3 ±1.6 and 10 0.1 ±0.3, respectively, in the control group (p<0.05, p<0.01).The level of Candida spp. from yeast-like bacteria was significantly higher in pregnant women of the comparison group compared to pregnant women of the main and control groups and was 10 1.1 ±0.3, 10 0.6 ±1.3 and 10 1.8 ±0.3, respectively (p<0.05, p<0.01).Of the mycoplasmas, Mycoplasma hominis was detected only in pregnant women of the main and comparison groups, and was not registered in pregnant women of the control group. 10 1.5 ± 0.3 in pregnant women of the main group and 10 0.9 ± 0.2 in pregnant women of the comparison group (p < 0.05, p < 0.01). The amount of ureaplasma (urealiticum-parvum) also increased by 5 and 4.2 times in pregnant women of the main and comparison groups compared to pregnant women of the control group (10 0.6 ± 1.2, 10 3.0 ± 0.3 and 10 2.5 ± 0.3, p < 0.05, p < 0.01, respectively).Of the pathogenic bacteria, Mycoplasma genitalium was detected only in 5.2% of pregnant women in the comparison group and was not detected in pregnant women in the main and control groups.Thus, a decrease in the number of lactobacilli in the vagina also reduces their production of antimicrobial peptides - bacteriocins. Bacteriocins, maintaining the environment at an acidic level, prevent the proliferation of opportunistic and pathogenic bacteria. A decrease in the number of bacteriocins leads to the formation of an alkaline environment in the vagina, which, in turn, is a condition for the development of opportunistic and pathogenic bacteria. Such changes in the vaginal environment increase the risk of termination of pregnancy in the first trimester of pregnancy.Taking into account the above, we conducted an analysis of the types of vaginal dysbiosis. The results of the analysis are presented in Fig. 1. | Figure 1. Frequency of vaginal dysbiosis between groups, % |

Analysis of the frequency of dysbiosis and normocenosis showed that 12.9% of the main group had pronounced dysbiosis, 25.8% had pronounced anaerobic dysbiosis, 4.8% had pronounced mixed dysbiosis, 4.8% had mild anaerobic dysbiosis, 29.1% had relative normocenosis, 9.7% had absolute normocenosis, and 12.9% were below the control threshold level.In the comparison group, 7.1% had severe dysbiosis, 19.3% had severe anaerobic dysbiosis, 7.1% had mild anaerobic dysbiosis, 29.8% had relative normocenosis, 21.1% had absolute normocenosis, and 15.6% were below the control threshold, while severe mixed dysbiosis was not detected.In the control group, 10% had pronounced mixed dysbiosis, 10% had mild anaerobic dysbiosis, 20% had relative normocenosis, 50% had absolute normocenosis, and 10% had levels below the control threshold, while pronounced dysbiosis and pronounced anaerobic dysbiosis were not detected.Based on the above data, it can be argued that with a change in the structure of the vaginal microbiota - a decrease in lactobacilli and an increase in opportunistic and pathogenic bacteria, the level of pronounced dysbiosis in pregnant women increased, and the level of relative and absolute normocenosis decreased.Thus, the increase in vaginal microbiota from normocenosis to dysbiosis in pregnant women of the main group with a history of reproductive losses and the comparison group with retrochorial hematoma compared to the control group indicates that the risk of reproductive losses in pregnant women of this group is also closely associated with changes in the vaginal microbiota.

References

| [1] | Chen C., Song X., Wei W. et al. The microbiota continuum along the female reproductive tract and its relation to uterine-related diseases. – Nat. Commun., 2021. |

| [2] | Ravel J., Brotman RM Translational applications of the vaginal microbiome. – Science Translational Medicine, 2022. |

| [3] | Petrova M.I., Garcia- Fruitos E., De Boeck I. et al. Lactobacillus species as biomarkers and agents in the prevention and treatment of female urogenital diseases. – Front. Microbiol., 2020. |

| [4] | Romero R., Hassan S.S., Gajer P. et al. The composition and stability of the vaginal microbiota of normal pregnant women is different from that of non-pregnant women. – Microbiome, 2014. |

| [5] | Fettweis JM, Serrano MG, Brooks JP et al. The vaginal microbiome and preterm birth. – Nat. Med., 2019. |

| [6] | Kindinger LM, Bennett PR, Lee YS et al. The interaction between maternal microbiota and the immune system during pregnancy and its impact on preterm birth. – J. Reprod. Immunol., 2017. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML