-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2025; 15(1): 73-78

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20251501.13

Received: Dec. 26, 2024; Accepted: Jan. 16, 2025; Published: Jan. 18, 2025

Difficulties in the Early Differential Diagnosis of Botulism with Neurological Diseases

Laziz N. Tuychiev, Zulfiya S. Maksudova, Akramjon B. Abidov, Mavluda T. Karimova, Gulrukh Yu. Sultonova, Jakhongir A. Anvarov

Tashkent Medical Academy, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Foodborne botulism, caused by the ingestion of botulinum neurotoxin from improperly processed foods, remains a rare yet life-threatening condition. It often begins with gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, followed by descending flaccid paralysis, which can lead to respiratory failure if untreated. Early diagnosis is challenging due to the similarity of initial symptoms with common gastrointestinal diseases, and the disease's later neurological manifestations overlap with various neurological conditions, such as myasthenia gravis and stroke. This article discusses the difficulties in the early differential diagnosis of botulism, highlighting two clinical cases where botulism was initially misdiagnosed. The patients presented with typical gastrointestinal complaints and rapidly developed neurological signs, including cranial nerve palsies, ptosis, and dysphagia. The importance of a high clinical suspicion, particularly when patients report consuming home-preserved foods, is emphasized. Timely administration of botulinum antitoxin is critical to prevent severe complications. The article underscores the role of differential diagnosis in distinguishing botulism from other neurological diseases, the importance of laboratory confirmation, and the ongoing public health risk in areas with prevalent home canning practices. Increased awareness and proper food handling education are essential for preventing botulism outbreaks.

Keywords: Foodborne botulism, Differential diagnosis, Neurological symptoms, Gastrointestinal symptoms, Clinical diagnosis

Cite this paper: Laziz N. Tuychiev, Zulfiya S. Maksudova, Akramjon B. Abidov, Mavluda T. Karimova, Gulrukh Yu. Sultonova, Jakhongir A. Anvarov, Difficulties in the Early Differential Diagnosis of Botulism with Neurological Diseases, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 15 No. 1, 2025, pp. 73-78. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20251501.13.

1. Introduction

- Foodborne botulism is a rare but serious illness caused by the ingestion of preformed botulinum neurotoxin, primarily from improperly processed foods. The clinical presentation typically includes gastrointestinal symptoms followed by descending flaccid paralysis, which can lead to respiratory failure if not promptly treated. Understanding the epidemiological and clinical features is crucial for effective diagnosis and management [1,2].Foodborne botulism often arises from home canning, leading to sporadic cases and local outbreaks. Foodborne botulism is infrequent, with reported cases in Switzerland being less than one per year [3]. Epidemiological features of foodborne botulism in Tajikistan showed 132 cases, predominantly in adults (62%). Clinical features included severe forms in 45.8% of children, with symptoms like ophthalmoplegia (70.8%) and respiratory distress (20.8%), primarily after consuming homemade vegetable preserves [4]. In China, 80 outbreaks occurred from 2004-2020, with home-prepared foods like stinky tofu being common sources. Seasonal peaks were noted, particularly in summer months [5].The clinical presentation of botulism has its own characteristics and consists of several main syndromes: paralytic, gastrointestinal, and intoxication. In 30-50% of cases, the disease begins with the gastrointestinal syndrome. The disease manifests as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and dry mouth, which can resemble acute intestinal diseases (foodborne toxicoinfection (FTI), acute gastroenteritis, salmonellosis, etc.), i.e., acute digestive organ pathologies (intestinal syndrome, exacerbation of chronic gastritis, acute pancreatitis, etc.). In botulism, it should be noted that the signs of FTI persist for a short period (1-2 days). These symptoms disappear with the appearance of neurological signs [1,6].In botulism, patients complain of visual disturbances such as blurriness, the appearance of a grid in front of the eyes, diplopia, ptosis, and difficulty reading. As a result, patients primarily seek consultation with an ophthalmologist. Ophthalmoplegic symptoms play a crucial role in diagnosing botulism: ptosis, impaired convergence and accommodation of the eyeballs, mydriasis, abnormal light response, weakened corneal reflexes, horizontal nystagmus, diplopia, and bulbar symptoms—difficulty speaking due to soft palate paralysis, absence of reflexes from the posterior pharyngeal wall and root of the tongue, uvular paralysis (water may spill out when drinking), swallowing difficulties, acute respiratory insufficiency due to paralysis of the respiratory muscles, speech impairments, and dry mouth resulting from autonomic nervous system disturbances. The epidemiological factor also plays an important role. Additionally, differential diagnosis of botulism must be carried out with neurological pathologies (acute cerebrovascular accidents, encephalitis, myasthenia, etc.). The paralytic syndrome in botulism is symmetrical, bilateral, without sensory disturbances. The assessment of the severity of neurological symptoms is subjective and depends on the physician's qualifications, which in many cases can lead to errors in evaluating the process [1].Botulism presents distinct clinical features that set it apart from other neurological diseases. Characterized by acute, descending flaccid paralysis, botulism typically begins with cranial nerve palsies, leading to symptoms such as diplopia, dysarthria, dysphagia, and dry mouth, while maintaining an alert mental status and absence of fever. In contrast, other neurological conditions often exhibit sensory involvement or altered mental status [7].Initial symptoms include gastrointestinal distress, followed by neurological signs such as cranial nerve impairment and muscle weakness. The diagnosis is primarily clinical, often confused with other conditions like myasthenia gravis [8,9].Foodborne botulism is characterized by acute symmetric descending flaccid paralysis, often underdiagnosed due to symptom overlap with conditions like stroke and myasthenia gravis. Diagnosis is clinical, supported by laboratory confirmation of botulinum neurotoxins in specimens [8]. Most patients experience a bilateral, symmetric, descending paralysis. Common findings include ocular weakness, with 84% of cases reporting at least one ocular symptom. Absence of Sensory Symptoms: Botulism typically lacks sensory deficits, differentiating it from conditions like Guillain-Barre syndrome, which often includes sensory changes [7]. Early respiratory involvement is common, with 42% of patients presenting with respiratory distress [10].Conversely, conditions such as myasthenia gravis and Guillain-Barre syndrome may present with overlapping symptoms, including weakness and ocular signs, but they often include sensory involvement and fluctuating symptoms, complicating differential diagnosis [7].Immediate administration of antitoxin is critical, as delayed treatment can lead to severe complications. Despite its rarity, foodborne botulism remains a significant public health concern, particularly in regions with prevalent home canning practices. Increased awareness and education on safe food handling are essential to prevent outbreaks [8].

2. Clinic Case Presentation

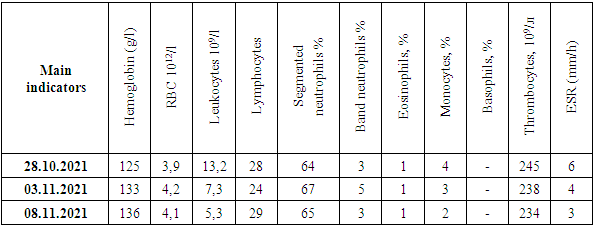

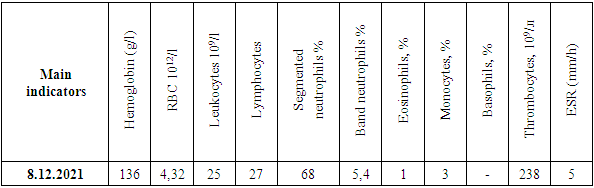

- Clinical Case No. 1Patient A., 40 years old (born in 1983), was hospitalized on October 28, 2021, at the Republican Specialized Scientific-Practical Medical Center for Epidemiology, Microbiology, Infectious, and Parasitic Diseases (RSSPMCEMIPD) with complaints of severe general weakness, dizziness, headaches, hoarseness, slowness, drooping eyelids, as well as difficulty swallowing food and water.Epidemiological history and medical history: On October 21, the patient worked in the field, where during a break he ate salted tomatoes and cucumbers from homemade preservation, and also drank wine. The next day, October 22, he experienced vomiting and diarrhea up to 5 times a day, after which he sought treatment at the local infectious diseases clinic. From October 22 to 28, 2021, the patient received treatment on-site for "Botulism, severe course," during which he was administered botulinum antitoxin (BAT) at a dose of 1 unit daily for 4 days (October 24, 25, 26, and 27), along with infusion and detoxification therapy, including intravenous Thiotriazoline 4.0, intravenous Ascorbic acid 5% – 10.0, Piracetam 10.0, Dexamethasone 4 mg, Cefpirome + Sulbactam 1.0 twice daily, L-Lysine Escinate 10.0 + NaCl 0.9%-10.0 intravenously. Due to deterioration in his condition (worsening neurological symptoms, increased fever), on October 28, the patient was given 2 doses of BAT. At the referral of the chief infectious disease specialist of the region, the patient was transferred by air ambulance to the RSSPMCEMIPD with a diagnosis of "Botulism, severe course."Upon admitting at RSSPMCEMIPD, the patient’s general condition was severe. His consciousness was preserved, and he responded to questions meaningfully, though with delay. His physique was normal, with signs of undernutrition. No deformities in the musculoskeletal system. Bilateral ptosis, diplopia, blurred vision, and accommodation disorders were noted. The pupils were equal, with a reduced light response. His voice was hoarse. The throat was calm, with no vomiting reflex. The mucous membranes and skin were clean, pale, and slightly dry. Skin turgor was normal, and the limbs were warm. Body temperature was 37.0°C. No swelling or enlargement of peripheral lymph nodes. Swallowing water was difficult, with marked choking, and liquids leaked from the nose. Nasal breathing was unobstructed. On auscultation, weakened vesicular breathing was noted on both sides of the lungs. Respiratory rate was 24 per minute, oxygen saturation (SpO2) was 96-97% upon admission. Heart sounds were muffled, rhythm was regular, with a heart rate of 64 beats per minute. Blood pressure was 120/80 mm Hg. The tongue was dry with a white coating. The abdomen was soft, tender to palpation, and slightly bloated due to bloating. The liver and spleen were not enlarged on palpation and percussion. Diuresis was normal. The stool showed a tendency toward constipation, with weakened bowel peristalsis. The Pasternack sign was negative on both sides, and no meningeal symptoms were found. The general clinical laboratory data are shown in the table 1.

|

|

3. Discussion

- Foodborne botulism remains a rare but serious condition, often linked to the consumption of improperly processed or preserved foods. As outlined in the cases presented, the clinical symptoms of foodborne botulism are often subtle at first, mimicking common gastrointestinal infections, but they rapidly progress to life-threatening neurological manifestations, such as descending flaccid paralysis and respiratory compromise. The severity of these manifestations underscores the critical need for early diagnosis and prompt treatment, particularly with antitoxin therapy [11].The initial gastrointestinal symptoms, such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, often lead to confusion with other foodborne illnesses, making the diagnosis of botulism particularly challenging in the early stages. However, it is the subsequent neurological symptoms—especially cranial nerve involvement, including ptosis, diplopia, dysphagia, and hoarseness—that distinguish botulism from other conditions. As noted in both clinical cases, the progression from gastrointestinal symptoms to neurological dysfunction highlights the importance of vigilant monitoring for signs of botulism, especially when patients report consumption of home-preserved or inadequately processed foods. The lack of fever and the absence of sensory involvement are also critical differentiators from other potential causes of flaccid paralysis, such as Guillain-Barré syndrome or myasthenia gravis [12].In this context, the clinical presentation of botulism, with its hallmark descending paralysis and bulbar involvement, plays a key role in diagnosis. Early identification of these symptoms can significantly impact the patient's outcome, as rapid administration of botulinum antitoxin is essential to prevent further progression of the disease. In both clinical cases presented, the timely initiation of therapy, including the administration of botulinum antitoxin, played a crucial role in preventing severe outcomes such as respiratory failure and further neurological deterioration [9].The challenges in diagnosing botulism are compounded by its clinical overlap with other neurological conditions, such as myasthenia gravis and stroke. In these instances, differential diagnosis is crucial to avoid misdiagnosis, which could delay the appropriate treatment. The use of laboratory tests to confirm the presence of botulinum neurotoxin in clinical specimens remains the gold standard for definitive diagnosis, but clinical suspicion based on patient history and symptomatology is often the first step in identifying botulism [7].The epidemiological data on foodborne botulism highlight the ongoing risk, particularly in regions where home canning or preservation practices are common. In the reported case from Tajikistan, the high incidence of botulism in children following consumption of homemade vegetable preserves underscores the importance of public health education regarding safe food preservation techniques. Similarly, outbreaks in China related to stinky tofu emphasize the need for vigilance and preventive measures, especially during warmer months when the risk of bacterial growth is heightened [4,5].Although foodborne botulism is infrequent in countries like Switzerland, its severity and potential for rapid deterioration make it a significant public health concern. In these regions, the rarity of cases should not lead to complacency, and healthcare professionals must remain vigilant in recognizing the clinical signs of botulism and initiating appropriate treatment without delay [3].

4. Conclusions

- Foodborne botulism is a potentially fatal disease that requires prompt clinical recognition and treatment. The presentation of gastrointestinal symptoms followed by rapid progression to neurological deficits requires immediate attention. Early intervention, particularly with botulinum antitoxin, is crucial to mitigate the severity of the disease and prevent complications like respiratory failure. The epidemiological findings further highlight the importance of awareness and preventive measures, including education on safe food processing, to reduce the incidence of this rare but dangerous illness. Due to the lack of necessary reagents in some hospitals for laboratory confirmation of the botulism diagnosis, the analysis of the literature and the review of the clinical case of botulism emphasized the importance of early differential diagnosis of this condition with neurological diseases.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML