-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2024; 14(12): 3328-3333

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20241412.53

Received: Nov. 9, 2024; Accepted: Dec. 6, 2024; Published: Dec. 28, 2024

Screening for Diabetic Retinopathy in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus in Urban and Rural Areas

Xurshid Mamajanov1, Azizbek Ikramov2

1PhD Student, Department of Ophthalmology, Andijan State Medical Institute, Andijan, Uzbekistan

2DSc., Professor, Department of Ophthalmology, Andijan State Medical Institute, Andijan, Uzbekistan

Correspondence to: Xurshid Mamajanov, PhD Student, Department of Ophthalmology, Andijan State Medical Institute, Andijan, Uzbekistan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Diabetic retinopathy is one of the most common complications of diabetes. In the early stages of the disease, it can be asymptomatic, especially in the initial phases of diabetes. Screening examinations allow for the detection of diabetic retinopathy at early stages. The prevalence of diabetic retinopathy varies between urban and rural populations. Therefore, we conducted a screening examination for diabetic retinopathy among 860 patients (1714 eyes) with newly diagnosed type 1 and type 2 diabetes in the Andijan region. The aim of the examination was to determine the extent of hidden diabetic retinopathy among urban and rural populations and to compare its levels. As a result of the examination, diabetic retinopathy was detected in 13% of urban residents with type 1 and type 2 diabetes and in 30% of rural residents with type 2 diabetes, and necessary treatment measures were prescribed. The likelihood of developing diabetic retinopathy in rural residents with diabetes is 2.5 times higher than in urban residents with diabetes.

Keywords: Diabetic retinopathy, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes, Visual acuity, Screening examination, Rural population, Urban population

Cite this paper: Xurshid Mamajanov, Azizbek Ikramov, Screening for Diabetic Retinopathy in Patients with Diabetes Mellitus in Urban and Rural Areas, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 14 No. 12, 2024, pp. 3328-3333. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20241412.53.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- DR is one of the most prevalent complications of DM and can lead to significant vision loss. The subclinical course of DR poses a particular challenge, as patients may not experience symptoms in the early stages of the disease, thereby complicating timely diagnosis and treatment [11]. DR is one of the most prevalent complications of diabetes, potentially leading to significant vision loss and blindness [7]. DR (DR) develops in 75% of patients with DM within 10 years of disease onset. In some cases, the living conditions and lifestyle of patients can influence the development, course of diseases, and the occurrence of complications. There are differences in the development of diabetic retinopathy among urban and rural populations in patients suffering from diabetes. Elevated blood glucose levels induce destructive changes in the walls of small blood vessels, including the destruction of pericytes and endothelial cells, thickening of the basement membrane, and aggregation of platelets and erythrocytes, which accelerates blood clotting and reduces blood flow. This leads to increased filtration of blood elements into tissues and irreversible organic changes [15]. DR can develop without any clinical symptoms until the diagnosis of DM [6]. In such cases, the diagnosis and treatment of DR are delayed. Consequently, it becomes challenging to prevent significant vision loss. Complications of DM lead to patients transitioning from an active to a passive state, limiting their work capacity and causing disability, while the applied treatment methods often fail to yield positive outcomes. In some cases, patients in the early stages of the disease relate to their health indifferently and neglect examinations of endocrinologists and ophthalmologists. The absence of physiological and psychological awareness of the complications of diabetes in patients, as well as an indifferent attitude to the early symptoms of DR can lead to the development of severe and incurable stages of complications [4]. Untimely intake of medications that lower blood sugar levels, excessive physical exertion, or negligence can contribute to the early development of diabetic retinopathy. Conversely, mental work and adherence to prescribed diets can slow down the progression of diabetic retinopathy [3]. In patients, DR may develop in one eye, leading to reduced visual acuity (VA) in that eye, while the other eye remains asymptomatic. Consequently, patients may not notice any clinical symptoms related to vision. This results in the loss of valuable time for implementing prescribed treatment methods for DR. Currently, the following methods are employed for the treatment of DR: laser photocoagulation, intravitreal injections of anti-VEGF agents, and vitreoretinal surgery, which play a crucial role in treating DR and limiting its pathological zones [2]. However, these methods do not always demonstrate their effectiveness in preventing the decline in VA among patients, and in some cases, VA may continue to deteriorate compared to the initial state. Therefore, current research is ongoing to explore new treatment methods for DR and to refine existing treatment approaches. The primary objective of ongoing research in ophthalmology is the prevention of DR development and the arrest of identified pathological processes [8]. Data obtained from screening examinations allow for the identification of risk factors contributing to the early development of diabetic retinopathy, as well as factors that can slow its progression or contribute to the regression of diabetic retinopathy [10]. Ophthalmologists should detect DR at its early stages using contemporary diagnostic methods and integrate visualization techniques for these changes into clinical practice [12]. To achieve this objective, it is essential to conduct and implement SE for DR among patients with recently diagnosed DM [9]. Screening examinations allow for the organization of diabetes management processes among urban and rural populations by analyzing their daily lifestyle and work activities. This enables the analysis of the pathogenesis of diabetic retinopathy and the development of necessary recommendations for the active life of other patients [13]. SEs are a crucial preventive measure for preserving VA in patients and preventing blindness. They enable the timely detection of DR and facilitate the prompt implementation of prescribed treatment methods [3]. The implementation and conduct of SE are highly effective in preventing future vision problems. SE for DR in patients with DM play a crucial role in detecting early signs of DR and facilitating the timely application of prescribed treatment methods [2]. Conducting SE for DR in remote areas among populations affected by DM is crucial for preventing the decline in VA and blindness. Such screenings can potentially contribute to the preservation of patients' active work capacity in the future [10]. The detection of early-stage DR, specifically non-proliferative DR, and the subsequent limitation of degenerative fields and regression of the pathological process play a crucial role in preserving VA in patients. This also confers economic and social benefits to the patients [1]. We conducted SE for DR among patients with recently diagnosed DM and identified the benefits of this method. The goal and objectives of the study are to conduct screening examinations for diabetic retinopathy among patients with newly diagnosed type 1 and type 2 diabetes living in urban and rural areas, in order to determine the prevalence of diabetic retinopathy and identify differences between these groups.

2. Materials and Methods

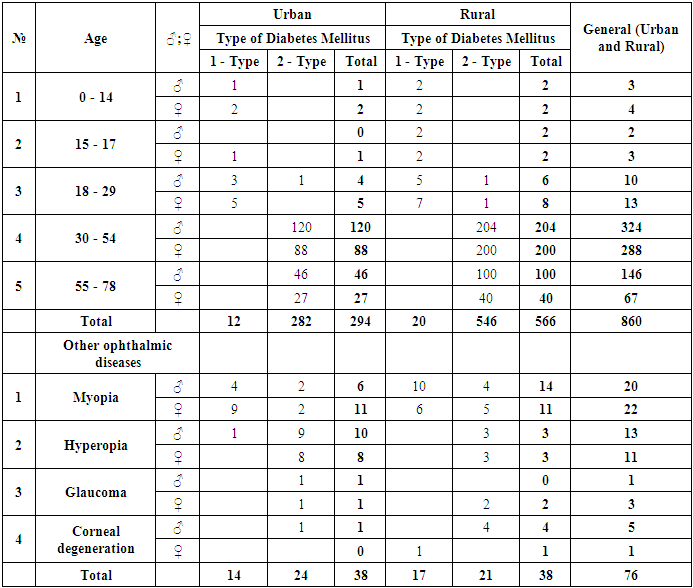

- For our study, we selected 860 patients (1714 eyes) with newly diagnosed diabetes from the urban and rural populations of the Andijan region and conducted a screening examination for diabetic retinopathy on a voluntary basis. Of these, 566 individuals (66%) were rural residents, and 294 individuals (34%) were urban residents. The examination was carried out at the Andijan branch of the Republican Specialized Scientific-Practical Medical Center of Endocrinology the majority of patients were examined in both outpatient and inpatient settings. The duration of DM ranged from 0.1 to 2 years. The age of the patients varied from 12 to 78 years. Among them, female accounted for 375 individuals (44%), and male accounted for 485 individuals (56%) (Table 1). Type 2 DM was diagnosed in 828 (96%) patients, while type 1 DM was diagnosed in 32 (4%) patients. Additional chronic eye diseases were detected in 76 patients (9%) (142 eyes). Among the patients, 42 individuals (5%) (82 eyes) had myopia, and 24 individuals (3%) (48 eyes) had hyperopia. These patients utilized prescribed eyeglasses and contact lenses. In 6 patients (0.7%) (6 eyes), VA was 0 (zero) due to injuries sustained during their lifetime. In 4 patients (0.5%) (6 eyes), glaucoma was diagnosed, and appropriate eye drop medications were prescribed. Among them, 294 individuals (34%) (564 eyes) are urban residents. This includes 12 individuals (1.3%) with type 1 diabetes and 282 individuals (33%) with type 2 diabetes. Children account for 3 individuals (0.4%), including 1 boy (0.1%) and 2 girls (0.2%). There is 1 adolescent (0.1%), a girl. Young adults account for 9 individuals (1%), including 4 men (0.5%) and 5 women (0.6%). Middle-aged individuals account for 208 people (24%), including 120 men (14%) and 88 women (10.2%). Elderly individuals account for 73 people (8.4%), including 46 men (5.3%) and 27 women (3.1%). Rural residents account for 566 individuals (66%) (1150 eyes). This includes 20 individuals (2.3%) with type 1 diabetes and 546 individuals (63%) with type 2 diabetes. Children account for 4 individuals (0.5%), including 2 boys (0.2%) and 2 girls (0.2%). Adolescents account for 4 individuals (0.5%), including 2 boys (0.2%) and 2 girls (0.2%). Young adults account for 14 individuals (1.6%), including 6 men (0.7%) and 8 women (0.8%). Middle-aged individuals account for 404 people (47%), including 204 men (24%) and 200 women (23%). Elderly individuals account for 140 people (16.2%), including 100 men (12%) and 40 women (4.6%).

|

3. Results and Their Discussions

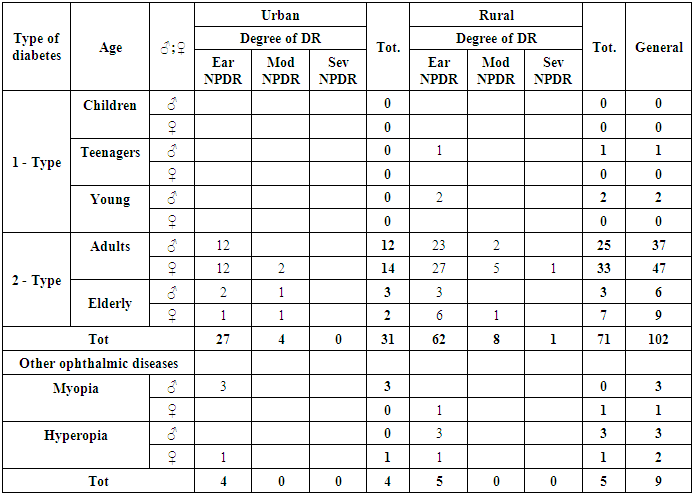

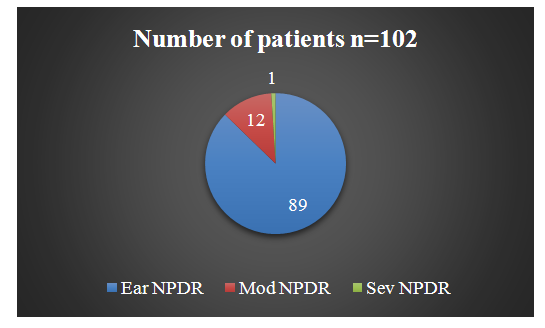

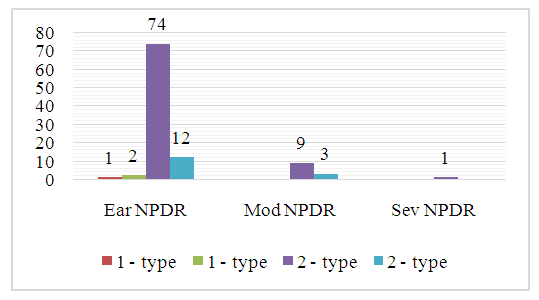

- We conducted SE for DR in 860 patients (1714 eyes) and obtained the following results: signs of DR were detected in 102 patients (12%) (177 eyes) (Diagram 1). The following types of DR were identified in accordance with the contemporary classification:1. Early nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy (Ear NPDR).2. Moderate nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy (Mod NPDR).3. Severe nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy (Sev NPDR).

| Diagram 1. Distribution of Identified DR by Classifications |

|

| Diagram 2. Distribution of Patients with DR by Age and Types of DM |

4. Conclusions

- Based on the conducted research, the following conclusions can be drawn:1. The SE method for DR constitutes a specialized diagnostic technique aimed at detecting DR in patients with DM. This method enables the identification of early pathological signs of DR in the initial stages of DM. The SE method for DR plays a pivotal role in preventing the progression of DR to severe stages. As a result, the likelihood of vision loss is reduced, and visual function is preserved.2. Given that DR can develop asymptomatically in the early stages of the disease, timely screening for DR plays a crucial role in preventing disability caused by ocular complications. Screening for DR enables the timely identification of pathological processes and the prompt application of appropriate therapeutic interventions. This is pivotal in preventing the progression of DR to severe stages and in reducing future treatment costs.3. Utilizing this method, general information can be obtained regarding micro- and macroangiopathies occurring in other parts of the body, based on early pathological processes in the retinal vessels. This facilitates multidisciplinary collaboration with specialists from other fields, thereby enabling the preservation of patients' active life activities and work capacity.4. Among patients with diabetes living in urban areas, diabetic retinopathy is rarely encountered in the early stages of the disease. The main reasons for this include having sufficient information about diabetes, timely intake of medications to lower blood sugar levels according to the prescribed regimen, and greater focus on mental work compared to physical labor. Additionally, they lead an active lifestyle, avoid negligence, and adhere to safety guidelines.5. Among patients living in rural areas, diabetic retinopathy develops earlier for the following reasons: their attention and daily lifestyle are focused on heavy physical labor, they do not take medications to lower blood sugar levels at the prescribed times and according to the regimen, they do not pay attention to the treatment of concomitant diseases, and they do not follow the rules for complete treatment. They rarely or never visit an endocrinologist and ophthalmologist. The presence of negligence among middle-aged and elderly patients also accelerates the development of diabetic retinopathy and other vascular diseases.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML