-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2024; 14(12): 3154-3157

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20241412.14

Received: Nov. 22, 2024; Accepted: Dec. 9, 2024; Published: Dec. 10, 2024

Dynamics of the Frequency of Thyroid Nodules in Adolescents Kashkadarya Region by Districts

Kholikova Adliya Omanullaevna1, Saidova Gulchekhra Sobirjonovna2

1Doctor of Medical Sciences, Head of the Department of Neuroendocrinology Republican Specialized Scientific and Practical Medical Center of Endocrinology of the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Uzbekistan named after academician E.Kh. Turakulov, Medical Association of Kitab District, Kashkadarya Region, Tashkent, Republic of Uzbekistan

2Endocrinologist of the Endocrinology Department of the Medical Association of the Kitab District of the Kashkadarya Region, Kashkadarya Region, Kitab District, Tashkent, Republic of Uzbekistan

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

To study dynamics of the frequency of thyroid nodules in adolescents Kashkadarya region by districts. At the polyclinic of the Kashkadarya branch of the Republican Specialized Scientific and Practical Medical Center of Endocrinology of the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Uzbekistan named after academician E.Kh. Turakulov, from 2020 to 2024, 568 adolescents with nodular diseases of the thyroid gland aged 11 to 15 years were examined. Of these, there were 461 girls and 107 boys. Over the period from 2020 to 2024, there was a tendency towards a slight decrease in the number of adolescents with nodular thyroid diseases in the Kashkadarya region. Thyroid problems in adolescents may present as a goiter, a nodule, or a general set of abnormal symptoms and physical findings. The unique challenge for adolescents is that thyroid problems can adversely affect growth and development during puberty, a critical period of hormonal interaction.

Keywords: Nodular goiter, Adolescents, Complications

Cite this paper: Kholikova Adliya Omanullaevna, Saidova Gulchekhra Sobirjonovna, Dynamics of the Frequency of Thyroid Nodules in Adolescents Kashkadarya Region by Districts, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 14 No. 12, 2024, pp. 3154-3157. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20241412.14.

1. Introduction

- Although the incidence of differentiated thyroid cancer (DTC) in children and adolescents (DTC) is low, it has been steadily increasing in recent years [1-3]. Compared with thyroid cancer in adults, DTC has clear differences in terms of pathophysiological characteristics, clinical features and long-term prognosis. [4-7]. Therefore, treatment guidelines and strategies developed for adult patients with thyroid cancer are not fully applicable to children and adolescents. The American thyrodological the Association of Thyroid Cancer (ATA) published its first guidelines for the diagnosis and management of childhood thyroid nodules and DTC in 2015, with the aim of standardizing the management of patients with DTC. [8]. The 2022 European Thyroid Association Guidelines for the management of thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer in children were prepared by an expert group. The expert group formulated this guideline specifically for children under 18 years of age with a thyroid nodule or differentiated thyroid carcinoma (DTC). Specific recommendations for the management of DTC in this age group are needed because of the differences in the presentation and genetics of DTC and the importance of treatment-related late effects of DTC in young people. [9].Treatment of thyroid nodules in children is challenging because the obvious goal is to identify children with a malignant nodule, as a benign nodule does not always require treatment. Thyroid cancer is very rare in childhood with a reported prevalence of 1:1,000,000 in children under 10 years of age and up to 1:75,000 in children aged 15–19 years when diagnosed based on clinical signs and symptoms. [10]. In population screening, ultrasound may detect small, clinically undetectable DTCs at higher rates, without evidence that treatment of such nodules will reduce mortality rates or improve patient outcomes. [11]. The prevalence of benign thyroid nodules in childhood has been described to be approximately 0.5–2% depending on the screening or palpation method [12]. or ultrasound [13], and from the definition of the size that is documented (>5 mm or >10 mm). When proposing thyroidectomy for benign disease, one should keep in mind the possible lifelong adverse effects of the surgery, beginning with the lifelong need for levothyroxine (LT4) replacement therapy after thyroidectomy and, in a small but significant percentage of cases, permanent hypoparathyroidism, which will also require lifelong calcium and vitamin D replacement therapy. [14].In adults, asymptomatic small thyroid nodules are very common (increasing with age) and are often discovered incidentally [15]. Most of them remain asymptomatic for the rest of their lives.The expert group questioned the prevalence of non-clinically significant thyroid nodules in childhood (Appendix A, [Q9]). A literature search was conducted (Appendix B). The largest source of data was found from surveillance programs in Fukushima and other parts of Japan that were not contaminated (Aomori, Yamanashi, and Nagasaki). These data showed that the prevalence of ultrasound-detected thyroid nodules >5 mm or cysts >20 mm in Japanese children was about 1.0% (20). The prevalence of non-clinically significant thyroid nodules in childhood has been found to range from 0.6 to 2% (Appendix C) [16,17]. Based on these findings, the expert group suggests that prospective studies be conducted to improve the level of evidence to provide greater certainty in determining the prevalence of non-clinically significant thyroid nodules in childhood in different populations.Thyroid nodules in children are reported to have a two- to three-fold higher risk of malignancy compared to thyroid nodules in adults. Depending on the background iodine status of the country (due to the fact that thyroid nodules are more common in iodine-deficient countries), the risk that a clinically significant thyroid nodule (>1 cm) will become malignant is 20–25% in children compared to 5–10% for a thyroid nodule in adults, respectively. [18-20]. The above was the reason for the present study.

2. Material and Methods

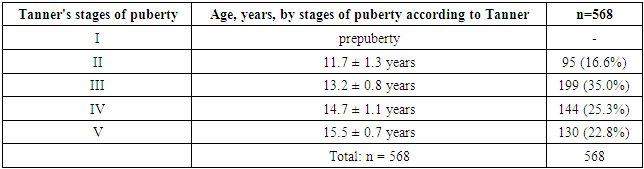

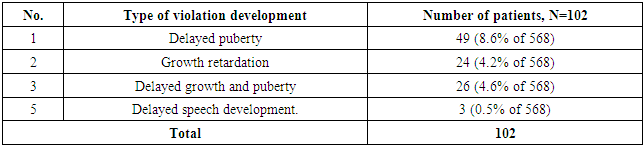

- At the polyclinic of the Kashkadarya branch of the Republican Specialized Scientific and Practical Medical Center of Endocrinology of the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Uzbekistan named after academician E.Kh. Turakulov, from 2020 to 2024, 568 adolescents with nodular diseases of the thyroid gland aged 11 to 15 years were examined. Of these, there were 461 girls and 107 boys.Inclusion criteria: children and adolescents with thyroid diseases, aged 0 to 18 years.Exclusion criteria: adults, over 18 years of age.Research methods– general clinical, biochemical (bilirubin, direct, indirect, ALT, AST, PTI, coagulogram, CRP), hormonal (TSH, free thyroxine, antibodies to TPO, to thyroglobulin and thyrocyte receptors, prolactin in the blood) and instrumental: ECG, ultrasound of the thyroid gland, internal organs, chest X-ray, etc.The analysis included American recommendations for thyroid nodules according to the ACR-TIRADS (American College of Radiology-Thyrpid Image Reporting and Data System) classification.Statistical software Microsoft Excel and STATISTICA_6 was used for statistical analysis, and p < 0.05 was considered a significant difference. Quantitative data with normal distribution were expressed as mean and standard deviation (M ± SD).

3. Results and Discussion

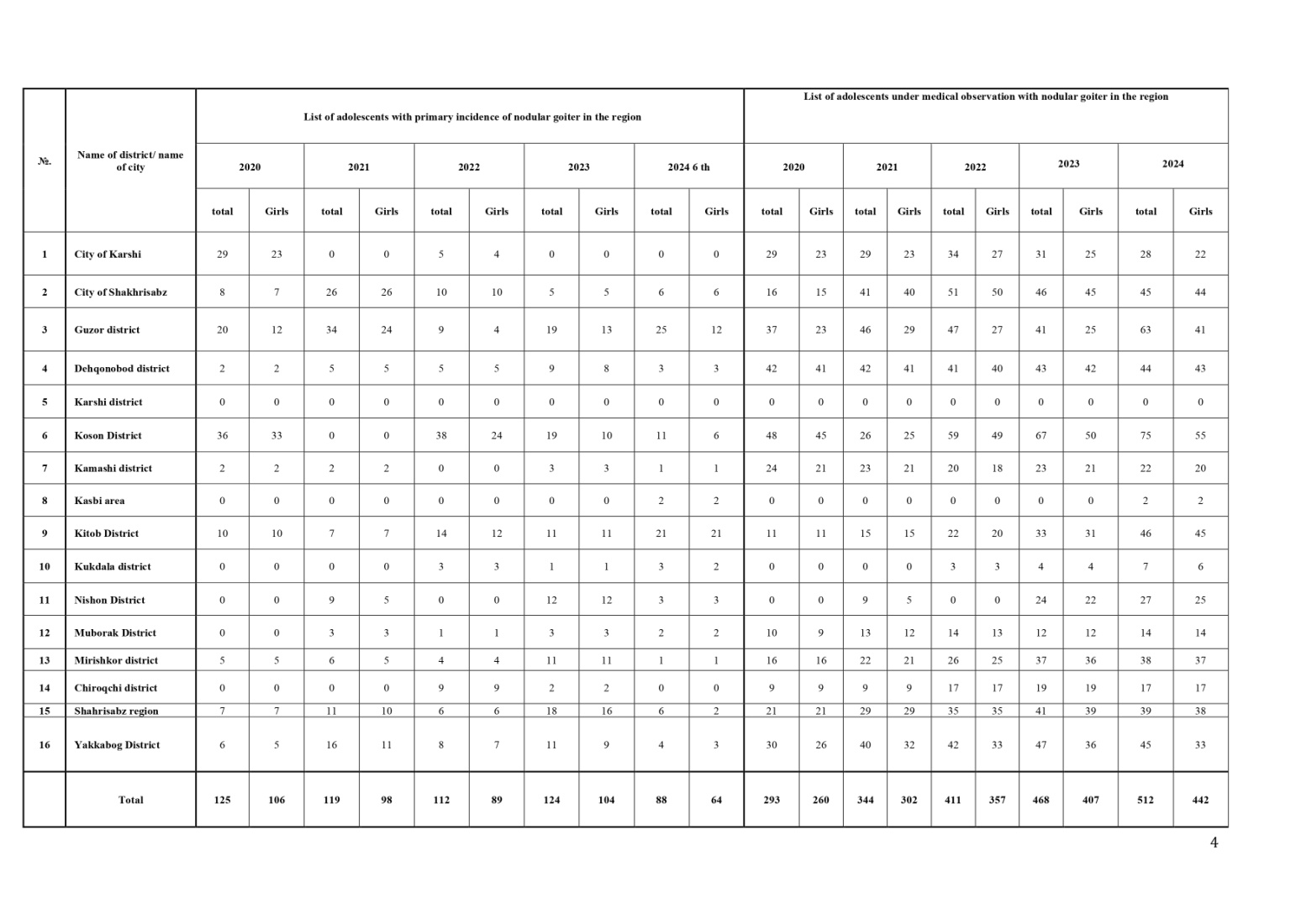

- Table 1 shows a list of adolescents with primary nodular goiter and registered for dispensary care in the Kashkadarya region. This table shows that over the period from 2020 to 2024, there was a tendency for a slight decrease in the number of adolescents with nodular thyroid diseases in the Kashkadarya region.

| Table 1. List of adolescents with primary nodular goiter and registered with the dispensary in the Kashkadarya region |

|

|

4. Conclusions

- Thyroid problems in adolescents may present as a goiter, a nodule, or a general set of abnormal symptoms and physical findings. The unique challenge for adolescents is that thyroid problems can adversely affect growth and development during puberty, a critical period of hormonal interaction.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML