-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2024; 14(12): 3127-3133

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20241412.10

Received: Nov. 1, 2024; Accepted: Nov. 21, 2024; Published: Dec. 10, 2024

Cause-and-Effect Relationships of Spinal Cord Injury Formation in Experimental Animal Models

Khikmatullaev R. Z., Iriskulov B. U.

Tashkent Medical Academy, Uzbekistan

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This article presents the pathophysiological mechanisms of spinal cord injury in animal models. Since secondary damage underlies the pathogenesis of spinal cord injury, we have established cause-and-effect relationships in the formation of spinal cord injury in a rat model, which is a pathogenetically substantiated method.

Keywords: Spinal cord injury, Cause and effect relationships, Pathogenesis, Secondary damage, Experimental study

Cite this paper: Khikmatullaev R. Z., Iriskulov B. U., Cause-and-Effect Relationships of Spinal Cord Injury Formation in Experimental Animal Models, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 14 No. 12, 2024, pp. 3127-3133. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20241412.10.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- According to the World Health Organization, injuries are one of the most common causes of death among the young population, while in the structure of injury rates among the adult population, spinal cord injury accounts for 0.8 to 20-26.2% of all musculoskeletal injuries with an incidence rate of 0.6 per 1000 people. Thanks to advances in medicine, rehabilitation, and care, individuals with spinal cord injuries often live for decades after the traumatic event. However, most face significant challenges, including limited mobility, sensory loss, organ dysfunction, high rates of secondary complications, and psychoemotional distress that affect all aspects of their lives. Furthermore, data from the United States have shown that the annual incidence of SCI is approximately 17,000 people per year, and the cost per patient with high tetraplegia in the first year is more than US $1 million [2,4].Recovery of spinal cord function depends on the remodeling and integrity of neural circuits. Plasticity of neural circuits is the basis for recovery of neural function. Spinal cord components are rarely exposed to inflammatory cells, and a specialized barrier maintained by astroglia exists between endothelial cells that restricts the movement of proteins and other molecules. In spinal cord injury, compressive forces exceed the tolerance of tissue components, resulting in axonal rupture and injury to neuronal cell bodies, myelinating cells, and vascular endothelium [3]. Neurogenic shock, hemorrhage, and subsequent hypovolemia and hemodynamic shock in patients with spinal cord injury lead to impaired spinal cord perfusion and ischemia. Increased tissue pressure in the edematous injured spinal cord and hemorrhage-induced spasm of intact vessels further impair the blood supply to the spinal cord. High levels of glutamate can cause excitotoxicity, oxidative damage and ischemia, while Ca2+-dependent nitric oxide synthesis can cause secondary spinal cord injury [1,5]. Pathological cascades from atrophy to apoptosis or necrosis can lead to neuronal deterioration in the brain due to local spinal cord injury. The traditional principle of repair is to promote regeneration and expansion of the corticospinal tract (CST) and restore connectivity with distal neurons, including decreasing the production of regeneration-related inhibitors such as chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans (CSPG)/NogoA/myelin-associated glycoprotein (MAP)/oligodendrocyte myelin glycoprotein (OMG) and even lipid metabolites in the microenvironment at the early stage of SCI or promoting axonal regeneration by harnessing the intrinsic growth capacity [7,10].However, the pathophysiological mechanisms of spinal cord injury are like a “black box” and are still not completely clear. Moreover, the role of each pathological mechanism of spinal cord injury, such as immune response and astrocytic scar formation, is controversial. Recently, transcriptome analysis, weighted gene coexpression network analysis (WGCNA) and single cell sequencing technology have been widely used in spinal cord injury research and provide better tools to clarify the pathophysiological mechanisms [8,11].

2. The Aim of the Study

- To identify the cause-and-effect relationships of the formation of spinal cord injuries using an experimental animal model.

3. Materials and Research Methods

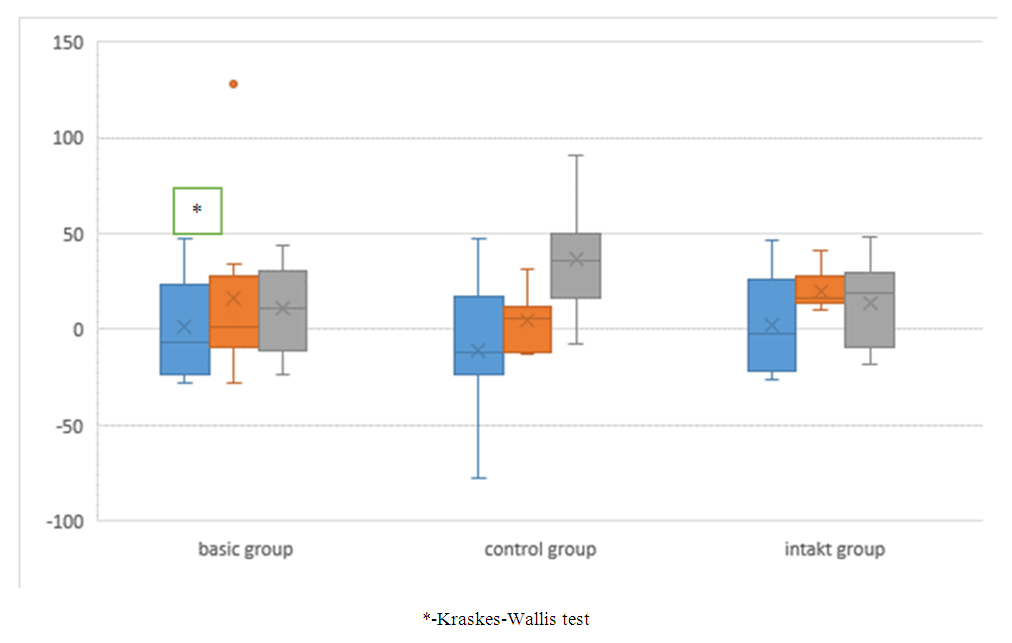

- The experiments were performed on 180 male rats using a spinal injury model. Experimental spinal injury is reproduced according to a modification of the standard model of moderate contusion spinal cord injury (Kubrak N.V., Krasnov V.V. 2015). Animal maintenance, surgical interventions and withdrawal from the experiment were carried out on the basis of the ethical principles declared by the European Convention for the Protection of Vertebrate Animals used for Experimental and Other Purposes. The animals were kept in a vivarium with free access to food and water and a natural alternation of day and night. The experiments were carried out under conditions of spontaneous breathing and an ambient temperature of 24-25°C.The experimental animals used were mongrel sexually mature male rats weighing 200-230 g. During the study, the animals were divided into three groups: the first control group - 6 animals that were kept in vivarium conditions during the entire experiment at t = 22°C. The second group, consisting of 20 animals, the lumbar spine of which was injured by a load weighing 250 g from a height of 20 cm. The third group included 20 animals, the lumbar spine of which was injured by a load weighing 250 g from a height of 40 cm. To carry out the manipulation, the animals were pre-anesthetized xylazine at a rate of 0.2 ml/kg. Rats in a state of narcotic sleep were fixed on a special board with their stomachs down. The planned area of the lesion was treated with a disinfectant solution - 20 mm above the base of the tail, which is at the level of the 3-4 lumbar vertebrae of the rats, the fur was cut off. The planned area of the lesion of the spinal column was brought to the guide tube, which was fixed to the tripod. In this case, the height of the tube from the surface of the rat's body was at the level of 20 cm and 40 cm.Statistical research methods were carried out using parametric and nonparametric methods. Comparison of two groups in the analysis of indicators measured on a quantitative scale and having a normal distribution was carried out using the parametric Student's t-test for independent groups. In case of data heterogeneity, comparison of two groups was carried out using the non-parametric test Mann Whitney.

4. Research Results

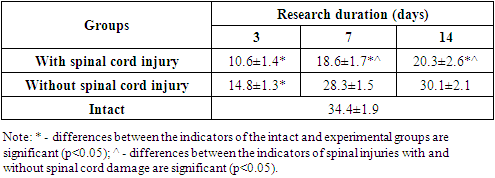

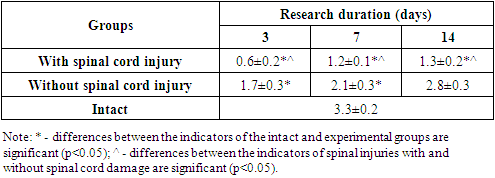

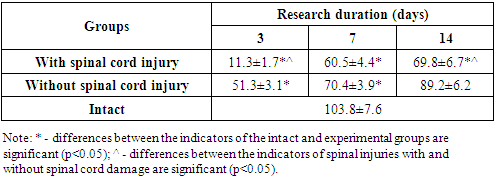

- The method for modeling lumbar spine injury with and without spinal cord injury is based on the effect of a mechanical factor in the form of a freely falling 250 kg weight from a height of 20 cm and 40 cm. A metal cylinder with a conical end is used as a weight to limit the injury site. For precise localization of the lesion site, a 40 mm diameter tube is installed above the rat's back, 20 cm and 40 cm high, into the lumen of which the weight is lowered. The precise localization of the injury site is determined by indenting 20 mm upward from the base of the rat's tail. Considering that the length of the lumbar spine of mature rats (200-230 g) is 48.8±1.43 mm, and the average cranio caudal size of the lumbar vertebral bodies is 7.46±0.39 mm, the indentation of the specified value from the base of the tail falls at the level of L III - L IV.Thus, on the third day after the injury, we found a significant decrease in voluntary locomotor activity in rats from the experimental group with spinal cord injury (SCI) and without spinal cord injury (WSCI) (see Table 1). However, the severity and duration of locomotor function disorders depended on both the duration of the experiment and the spinal cord injury. Thus, in rats without spinal cord injury on the 3rd day of the experiment, the number of drum movements decreased by 2.32 times (p<0.001), amounting to14.8±1.3 revolutions, with the value of this indicator in the intact group of rats being 34.4±1.9 rev. However, in subsequent periods we observed a gradual restoration of the values of this test, i.e. on the 7th day of the experiment this indicator statistically significantly increased by 1.92 times (p<0.01) relative to the values of the previous period of the study and amounted to 28.3±1.5 vol. At the same time, this indicator maintained a tendency to decrease relative to the values of intact rats. By the final period of the study (the 14th day of the experiment), this indicator had a tendency to increase and composed 30.1±2.1 rev., not significantly different from the values of intact rats. As can be seen from the data provided, any spinal injuries without damage to the spinal cord lead to transient disorders of the locomotor function of the spinal cord.

|

|

|

| Figure 1. Dynamics of changes in locomotor activity in rats during spinal cord injury modeling |

| Figure 2. Injury with an iron tube to a laboratory animal |

| Figure 3. External condition of a laboratory animal after injury |

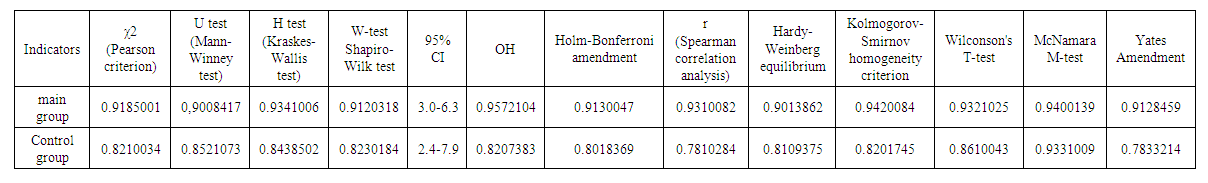

| Table 4. Some statistical indicators of spinal cord injury modeling in the experiment |

5. Conclusion and Discussion

- When choosing the optimal animal model for solving specific research problems, it is necessary to take into account many factors: the type, age, size, sex of the animals, the possibility of using visualization methods and functional assessment of their condition. Since the second half of the last century, methods for preventing the consequences of spinal cord injury have become the subject of systematic research on various animals, including rats, mice, cats, and dogs. The secondary injury process can be divided into several stages based on the time since injury and the pathomechanism: acute, subacute (or intermediate), and chronic phases. The acute phase is considered to last 48 hours after the initial physical injury. Neurogenic shock, hemorrhage, and subsequent hypovolemia and hemodynamic shock in patients with spinal cord injury lead to impaired spinal cord perfusion and ischemia. Larger vessels, such as the anterior spinal artery, usually remain intact, while rupture of smaller intramedullary vessels and capillaries that are susceptible to traumatic injury leads to extravasation of leukocytes and erythrocytes. Increased tissue pressure in the edematous injured spinal cord and hemorrhage-induced spasm of intact vessels further impair the blood supply to the spinal cord. Ultimately, vascular injury, hemorrhage, and ischemia lead to cell death and tissue destruction through multiple mechanisms including oxygen deprivation, adenosine triphosphate (ATP) loss, excitotoxicity, ion imbalance, and free radical generation. Cellular necrosis and cytoplasmic release increase extracellular glutamate levels, causing glutamate excitotoxicity. Restoration of blood flow to ischemic tissue (reperfusion) leads to further injury by generating free radicals and activating the inflammatory response. Furthermore, activated microglia and astrocytes, as well as infiltrating leukocytes from the periphery, release cytokines and chemokines that create a proinflammatory microenvironment. Together, this leads to progressive destruction of CNS tissue known as “bystander tissue injury,” which significantly impairs functional recovery. Literature data suggest the effectiveness of early surgical treatment of spinal cord injury. Although the optimal timing remains controversial, spinal cord decompression, vertebral stabilization, and maintenance of blood perfusion are critical factors in achieving optimal outcomes in this condition. Although many studies have reported improved neurologic outcomes with early surgical decompression, there is no consensus on the definition of early decompression: it has ranged from 4 hours to 4 days, but since 2010 there has been a trend toward decompression within 24 hours of injury. In particular, in cauda equina syndrome, surgical treatment within a 24-hour window has been shown to preserve pelvic function, with the poorest results obtained when decompression is performed after 48 hours of injury. The study D.-Y. Lee et al. (2018) found that surgical decompression of the spinal cord within 8 hours after spinal injury between C1-L2, compared with the time interval of 8-24 hours, significantly improves neurological recovery, which allowed the authors to recommend early decompression (within 8 hours) as an effective treatment for spinal cord injuries [6]. Similar data are presented by O. Tsuji et al. (2019): it was shown that patients with complete motor paralysis after a cervical spine fracture can recover to partial paralysis if surgical treatment is performed within 8 hours after injury [9]. Given the multifaceted mutually reinforcing effect of secondary spinal cord injury mechanisms, this approach seems pathogenetically justified.

6. Conclusions

- Summarizing the above, it is important to note that the cause-and-effect relationships of the formation of spinal cord injury lie in the study of the mechanisms of secondary damage, since the nature of further surgical treatment will depend on the degree of contracture of the muscles of the posterior spine.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML