-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2024; 14(10): 2587-2590

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20241410.30

Received: Sep. 28, 2024; Accepted: Oct. 12, 2024; Published: Oct. 23, 2024

Condition of the Main Indicators of Spermogram in Men Who Have Recovered from COVID-19

Kariev S. S.1, Abdurakhmanov K.2

1Department of Urology and Andrology, CPRMC, Ministry of Health of Uzbekistan

2Department of General Surgery, Pediatric Surgery, Urology, and Pediatric Urology, Termez Branch of Tashkent Medical Academy, Uzbekistan

Correspondence to: Abdurakhmanov K., Department of General Surgery, Pediatric Surgery, Urology, and Pediatric Urology, Termez Branch of Tashkent Medical Academy, Uzbekistan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

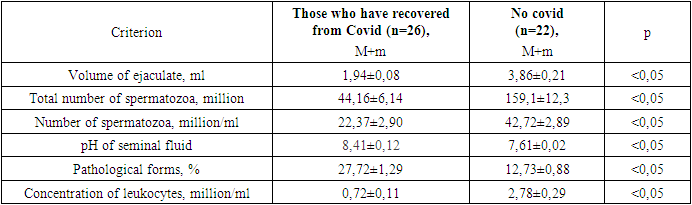

According to scientific studies, SARS-CoV-2 can negatively affect the male reproductive system. The aim of this study was to investigate the main indicators of seminal fluid in men after recovering from COVID-19 infection. The study analyzed the seminal fluid of 48 men, of which 26 had a history of COVID-19 infection, confirmed by laboratory tests. Key spermogram parameters such as ejaculate volume, total sperm count, sperm concentration, percentage of abnormal forms, seminal fluid pH, and leukocyte concentration were examined. Spermogram parameters of patients who recovered from COVID-19 were significantly different from those who had not contracted the infection. The ejaculate volume was reduced by 2 times, and the total sperm count was 3.6 times lower. Similarly, sperm concentration was almost halved. An increase in seminal fluid pH was observed, and the percentage of abnormal sperm forms was twice as high. Men who have recovered from COVID-19 and show elevated levels of IgG antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 in their blood have significant changes in fertility. These data indicate a decline in fertility, which may lead to reduced birth rates in the region. More in-depth studies are needed to confirm the suspected causes of the observed changes in the male reproductive system.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Male fertility, Male reproductive system

Cite this paper: Kariev S. S., Abdurakhmanov K., Condition of the Main Indicators of Spermogram in Men Who Have Recovered from COVID-19, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 14 No. 10, 2024, pp. 2587-2590. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20241410.30.

1. Introduction

- A meta-analysis published in 2017 indicates a 50-60% decrease in key spermogram parameters over four decades (1973-2011) [1]. The WHO constantly revises its recommendations for sperm analysis, and these values are gradually decreasing, indicating a tendency for sperm quality decline each year [2,3].Some researchers argue that these conclusions are incorrect, as they believe there is a lack of reliable data to confirm the reduction in sperm parameters over time. They claim that unreliable data and interpretations used throughout the last century are the source of the debate. However, modern data provide a clearer signal that neither sperm parameters nor male fertility have changed significantly over the last century [3].Environmental changes, exposure to chemicals, and a sedentary lifestyle have been identified as significant factors affecting spermatogenesis [4]. This trend is likely to intensify among the population, and future prospective studies should identify the potential causes of this decline. In light of recent years’ developments, particularly the impact of COVID-19, it is reasonable to expect deeper changes in male fertility indicators. According to recent studies, SARS-CoV-2 negatively affects the reproductive system, leading to a decrease in sperm count, motility, erectile function, and testosterone levels [5]. Given reports of declining sperm quality and birth rates in some regions, it is necessary to investigate whether human fertility is changing. This underscores the need for further research on this issue [6].The goal of this study was to investigate the main indicators of seminal fluid in men after recovering from COVID-19 infection.

2. Materials and Methods

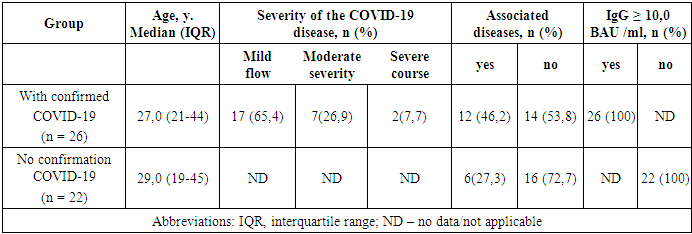

- Patient Characteristics: A total of 48 men were included in the study. Of these, 26 had recovered from COVID-19 with laboratory-confirmed infections (Group 1) – elevated IgG levels in blood serum. The average age of these patients was 26.3±2.7 years. The remaining 22 men, who had no subjective or laboratory signs of COVID-19 (Group 2), had an average age of 29.9±0.6 years. None of the men had been vaccinated against COVID-19 by the time of examination.Laboratory Studies: All patients underwent standard sperm analysis according to WHO recommendations [7,8]. Semen was analyzed using the SW-3700 analyzer (Manufacturer: MES, China). To ensure data accuracy, patients were instructed to:- Ensure all semen is collected in the sample cup;- Avoid using a condom for collection;- Abstain from ejaculation for two to seven days before the sample collection;- Collect a second sample within two weeks of the first;- Avoid lubricants, as they may affect sperm motility.The following key spermogram indicators were selected for analysis in this study:- Ejaculate volume,- Total sperm count,- Sperm concentration,- Percentage of abnormal sperm forms,- Seminal fluid pH,- Leukocyte concentration in seminal fluid.Statistical Analysis: Statistical analyses were performed using “Microsoft Excel 2013”, “Microsoft Access 2013”, and the statistical software package “R for Windows 2.15.0”. The mean (M), standard deviation (σ), and relative values (frequency, %) were calculated. Statistical significance was determined using Student’s t-test (for normally distributed data) and the Wilcoxon test (for non-normally distributed data). Confidence intervals (CI) were constructed for a confidence level of 95%, and p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

- Clinical Characteristics of Patients: The study included 48 male patients from Surkhandarya region who sought consultation at an outpatient andrology clinic. Of these, 26 had confirmed COVID-19 infection (1.5-2 months post-illness, no earlier than the 42nd day after the illness). The remaining 22 patients were examined for erectile dysfunction. Confirmed COVID-19 infection was determined by a positive SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibody test using Chemiluminescent Immunoassay (Sperm Quality Analyzer technology). Quantitative measurement ranged from 2.9 to 5680 BAU/mL. Comorbidities, such as autoimmune diseases or chronic infections, were excluded to avoid influencing the results.Spermogram Indicators: Spermogram indicators of patients who had recovered from COVID-19 significantly differed from those who had not contracted the infection. In Group 1, the ejaculate volume was reduced by 2 times, and the total sperm count was 3.6 times lower. The sperm concentration was almost halved, and seminal fluid pH was elevated. The percentage of abnormal sperm forms was twice as high compared to Group 2.

|

|

4. Discussion

- The changes identified in this study confirmed the anticipated deterioration in male fertility among the male population of the region. These findings are another piece of evidence supporting the projected decline in birth rates in the near future. Consequently, it can be expected that there will be an increase in referrals to specialized medical professionals in the field [4].It is essential for us to analyze the causal relationship between the detected alterations in the spermograms. It is known that if the pH of seminal fluid exceeds the normal level above 8.0, indicating an alkaline environment this often suggests the presence of inflammation or infection. Scientific studies have confirmed that infections can reduce male fertility through various mechanisms. These include disruptions to local immune regulation, leading to the development of autoantibodies against sperm, or impairments in the function of male accessory glands. As a result, the quality or quantity of seminal fluid may decrease. Additionally, pathogens can damage sperm directly or through the inflammation they cause [9,10,11].In our observations, another indicator of inflammation was the increased leukocyte concentration in the seminal fluid. Although none of the patients reported a history of epididymitis or orchitis during COVID-19, their leukocyte concentrations were four times higher than those in Group 2. This finding aligns with observations and literature reviews by Enikeev and colleagues [5].The role of aseptic inflammation is well-established in the pathogenesis of infertility, which is associated with oxidative stress, nitrosative stress, and hypoxia. The main sources of free radicals (FR) in ejaculate are morphologically abnormal spermatozoa, as well as leukocytes. The latter produce up to 1,000 times more FR than spermatozoa. On the one hand, this high production level of FR is necessary for antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory functions. On the other hand, an excessive amount of FR is associated with oxidative stress, which leads to the death or malfunction of sperm [13,14,15].COVID-19 can cause widespread endothelial dysfunction in organ systems beyond the lungs and kidneys. The virus is capable of penetrating endothelial cells and affecting many organs, including those in the male reproductive system [16]. This condition of the vascular system is another significant factor in the development of oxidative stress.In all of the above cases, antioxidants are effective in the treatment of patients with similar reproductive system disorders, especially in those complicated by excretory-toxic infertility [12,13]. Therefore, the use of combined antioxidant supplements, both during the treatment of COVID-19 and during post-infection rehabilitation, may be an appropriate strategy for optimizing fertility in patients affected by SARS-CoV-2 viral infection.

5. Conclusions

- Thus, for men who have recovered from COVID-19 and have elevated levels of IgG SARS-CoV-2 in their serum, significant changes in fertility are observed. Compared to similar indicators in individuals without subjective or laboratory signs of a past COVID-19 infection (with normal IgG SARS-CoV-2 levels in serum), there is a reduction in ejaculate volume and total sperm count, an increase in the percentage of abnormal sperm forms, and an elevated pH of the seminal fluid. Against the backdrop of a global trend toward declining key sperm parameters, these data indicate a deterioration in fertility and a potential decrease in birth rates in the region. To confirm the proposed causes of these observed changes in the male reproductive system, further in-depth studies are warranted.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML