-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2024; 14(10): 2579-2586

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20241410.29

Received: Sep. 21, 2024; Accepted: Oct. 17, 2024; Published: Oct. 23, 2024

Optimisation of Clinical Outcomes Through Modifying Addictive Attitudes in Alcohol Dependence

Rashidov Amir Ismailovich1, Ashurov Zarifzhon Sharifovich2, Syunyakov Timur Sergeevich3

1PhD Candidate, Bukhara State Medical Institute, Bukhara, Uzbekistan

2Director, Republican Specialized Scientific-Practical Medical Center of Mental Health, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

3Advisor to the Director, Republican Specialized Scientific-Practical Medical Center of Mental Health, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

Correspondence to: Rashidov Amir Ismailovich, PhD Candidate, Bukhara State Medical Institute, Bukhara, Uzbekistan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This study evaluated the effectiveness of a targeted intervention programme designed to modify addictive attitudes among individuals with alcohol dependence, aiming to improve treatment adherence and clinical outcomes. A single-blind clinical trial was conducted with 153 patients diagnosed with alcohol dependence syndrome, randomly assigned to an experimental group (n = 76) receiving standard treatment plus the intervention, and a control group (n = 77) receiving standard treatment alone. The intervention focused on analyzing and modifying addictive attitudes over 5–7 sessions using cognitive-behavioral techniques. Results indicated that the experimental group showed a significant reduction in scores on the McMullan-Gilhar Addictive Attitudes (MGAA) Test compared to the control group (p < 0.001), demonstrating the programme's effectiveness in modifying addictive attitudes in the short term. However, survival analysis over a one-year follow-up revealed no statistically significant difference in relapse rates between the two groups (p = 0.512). The Cox proportional hazards model did not identify significant predictors of relapse when considering all variables collectively. The findings suggest that while the intervention effectively modified addictive attitudes, this change did not translate into reduced relapse rates over one year. Modifying addictive attitudes is an important component of treatment but may not be sufficient alone to achieve sustained sobriety. A comprehensive, multifaceted approach addressing behavioral, environmental, and psychological factors is likely necessary to improve long-term outcomes for individuals with alcohol dependence.

Keywords: Alcohol dependence, Addictive attitudes, Treatment adherence, Cognitive-behavioral intervention, Relapse prevention

Cite this paper: Rashidov Amir Ismailovich, Ashurov Zarifzhon Sharifovich, Syunyakov Timur Sergeevich, Optimisation of Clinical Outcomes Through Modifying Addictive Attitudes in Alcohol Dependence, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 14 No. 10, 2024, pp. 2579-2586. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20241410.29.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Alcohol dependence remains one of the most prevalent chronic mental health disorders globally, yet only a minority of those affected seek professional treatment [1], [2]. This condition presents a serious global public health challenge, not only due to the direct costs associated with medical treatment and care but also because of the social and economic issues related to reduced productivity and increased expenses on law enforcement activities [3]. According to official data 2022, in the Republic of Uzbekistan, individuals registered with substance use disorders number around 5,000, while those with alcohol dependence exceed this figure by almost tenfold. Over the past five years, the incidence of newly diagnosed alcohol dependence in Uzbekistan has significantly increased [4].The contemporary approach to treating alcohol dependence involves a combined method based on medical, psychotherapeutic, and social interventions [5], [6]. However, in practice, treatment often halts immediately after detoxification therapy without adequate subsequent medical-social rehabilitation and psychosocial support. This contributes to the so-called "revolving door" phenomenon, where patients repeatedly admit themselves to inpatient care over a short period for detoxification courses [7]. Premature dropout from treatment programmes significantly impacts treatment effectiveness. Patients who discontinue treatment exhibit less favourable outcomes and a high level of dissatisfaction with the therapy provided [8]. The underlying issue here is the low adherence to treatment among patients with addiction profiles.Over the past decades, various methods for treating alcohol dependence have been studied. Nonetheless, the problem of insufficient patient adherence to treatment remains pressing and is associated with frequent disease relapses [5], [9], [10], [11]. Numerous studies in this field highlight the complexity of the adherence process, influenced by various factors [9], [11], [12], [13]. Conducting additional research aimed at exploring factors that affect patient adherence to medications and other methods for treating alcohol dependence is becoming an increasingly task. This is necessary to improve the quality and effectiveness of alcohol dependence treatment and reduce the risks of possible relapse [11], [14].

1.1. Addressing the Gap in Treatment Programmes

- Despite the availability of evidence-based treatments such as cognitive-behavioural therapy and motivational interviewing, there is a lack of programmes specifically aimed at analysing and modifying addictive attitudes with the goal of improving adherence to treatment. The proposed study aims to examine the clinical-psychopathological and social characteristics of individuals suffering from alcohol dependence, identifying factors that influence the formation of alcohol remissions and adherence to treatment. In response to this gap, we have developed a programme aimed at improving these aspects. The emphasis on analysing addictive attitudes and indicators of the programme's effectiveness—measured by inpatient days spent in the hospital and duration of sobriety—represents a relatively new approach and distinguishes this research from previous studies. Implementing the goals of this study and integrating its results into the practical activities of addiction treatment facilities may reduce the likelihood of alcohol dependence relapse and thereby contribute to enhancing the overall effectiveness of treatment.

1.2. Hypothesis

- In this study, we aim to determine whether the intervention programme we developed is effective for individuals with alcohol dependence syndrome. This is the primary hypothesis, focusing on how the programme impacts treatment adherence. Our key outcomes include sustained sobriety and the number of inpatient days spent in the clinic. We hypothesise that the intervention will positively influence these outcomes, leading to improved adherence to treatment and better clinical results.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

- Patients with a verified diagnosis of "Alcohol Dependence Syndrome" undergoing inpatient treatment in addiction treatment facilities. Inclusion Criteria: A verified diagnosis of F10.2 "Alcohol Dependence Syndrome" signed voluntary informed consent to participate in the study, patient age between 18 and 65 years, and at least 7 days since hospital admission. Exclusion Criteria: Presence of alcohol withdrawal syndrome at the time of assessment, dependence on another psychoactive substance (except for nicotine), objective reasons preventing verbal contact, presence of comorbid psychiatric disorders, and history of seizures outside of alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Exclusion Criteria After Inclusion: Withdrawal of consent to participate in the study after its commencement and identification of exclusion criteria during clinical interviews.

2.2. Research Design

- This study was conducted as a single-blind clinical trial with two groups: an experimental group (Group 1) and a control group (Group 2). A total of 153 eligible participants were enrolled after screening, with 76 participants allocated to Group 1 and 77 to Group 2 through alternating allocation, ensuring balanced and unbiased distribution. The experimental group received standard treatment along with a specially designed programme aimed at correcting addictive attitudes and strengthening adherence to treatment. The control group received treatment according to established national standards and clinical protocols. Participants underwent pre- and post-testing to assess key variables, including characteristics of addictive attitudes, length of hospital stay, and period of alcohol abstinence. Follow-up assessments were conducted via telephone at 3 months, 6 months, and 1 year to monitor longer-term outcome.Initially, 174 potential participants were screened, with 8 declining consent and 13 not meeting inclusion criteria. Ultimately, 153 participants were successfully enrolled in the study. Over the course of the study, 3 participants from Group 1 and 7 from Group 2 withdrew or were lost to follow-up. As a result, 72 participants in Group 1 and 68 in Group 2 completed the full study protocol, resulting in a total of 140 participants who completed the study.

2.3. Randomization Process

- Participants were assigned to groups as they were admitted and provided consent. Each participant was sequentially assigned a number, with odd-numbered participants placed in Group 1 (experimental group) and even-numbered participants placed in Group 2 (control group).

2.4. Investigators

- The study was conducted under the supervision of the principal investigator, with the support of two psychotherapists, each possessing over three years of clinical experience in alcohol dependence treatment. The psychotherapists underwent specialised training in the intervention programme to ensure consistent and accurate implementation.

2.5. Programme Implementation Session

- The Programme Implementation Session is a structured approach designed to increase treatment adherence among patients with alcohol dependence. The programme is delivered over 5–7 sessions, each lasting 30–40 minutes, held 2–3 times per week, with sessions scheduled in advance, preferably in the morning. The session structure includes: Stage 1, Assessment (1–2 sessions), focusing on evaluating beliefs and attitudes; Stage 2, Informational Campaign (1–2 sessions), providing education about the effects of alcohol and available treatments; Stage 3, Working with Motivation (1–2 sessions), using tools like the Hierarchy of Values and Cost-Benefit Analysis to enhance motivation; Stage 4, Addressing Addictive Attitudes (3–5 sessions), applying cognitive therapy techniques such as the ABC Model and cognitive restructuring to challenge addictive beliefs; and Stage 5, Final Integration and Support (1 session), which evaluates progress and develops a follow-up plan, with monthly meetings for ongoing support.

2.6. Assessment Tools

- The Individual Patient Card consists of several sections that gather comprehensive information about the patient. The questionnaire covers the following domains: Section A: ICD-10 Criteria for Alcohol Dependence, which assesses the severity and characteristics of alcohol dependence through a series of structured questions; Section B: Disease History, which collects data on the patient’s personal and family medical history related to addiction and psychological conditions; Section C: Life History, focusing on childhood health, adolescent development, legal history, and educational background; Section D: Social Status, which evaluates current living conditions, family status, professional background, and social competence; Section E: Remissions and Therapy, detailing previous remissions and treatments, including rehabilitation programmes and therapeutic outcomes; and Section F: Attitudes Toward Treatment, assessing the patient's readiness for treatment, motivation for sobriety, and overall attitude toward achieving personal goal.The McMullan-Gilhar Addictive Attitudes (MGAA) Test is a psychometric tool designed to assess cognitive and emotional attitudes that may contribute to or sustain alcohol or substance dependence, consisting of 42 statements rated on a five-point Likert scale from "Strongly Agree" to "Strongly Disagree." Interpretation of Results: The test results help determine the severity of addictive attitudes, with scores of 110 points placing patients in the 50th percentile or higher, indicating more severe cases of dependence. These patients often display significant withdrawal symptoms, legal issues, and a history of multiple unsuccessful treatments. This test not only assesses the severity of dependence but also identifies cognitive factors that may impact treatment efficacy and relapse risk, allowing for classification of dependence severity and prediction of treatment response [15].The Stages of Change Readiness and Treatment Eagerness Scale (SOCRATES) was utilised as a diagnostic tool to assess the readiness of patients with alcohol dependence to change their behaviour. The scale comprised 19 statements to which patients responded on a scale of agreement or disagreement. The results identified the patient’s stage of "readiness to change," ranging from denial of the problem to active stages of change, and revealed their awareness of the problematic nature of their alcohol use as well as their motivation to change. Application in This Study: The scale was employed to identify correlations between the degree of readiness to change and other variables, such as treatment effectiveness, social status, and clinical-psychopathological characteristics. This aided in the development of individualised treatment programmes and in predicting treatment outcomes within the study population [15].The Quantitative Treatment Adherence Questionnaire was used to assess patient adherence to treatment in the study. The questionnaire was administered once to evaluate the patients' adherence to pharmacological therapy, medical support, and lifestyle modification. The results provided data to establish correlations between adherence and clinical outcomes, such as treatment effectiveness and patient readiness to change. This information contributed to the development of individualized treatment strategies and the prediction of treatment outcomes in the patient population [16].

2.7. Statistical Analysis

- In the statistical analysis, quantitative variables with a normal distribution were described using the mean (M) and standard deviation (SD), whereas for variables with a non-normal distribution, the median (Me) and interquartile range (Q1; Q3) were used. Categorical variables were presented as absolute (n) and relative (%) frequencies.The normality of quantitative variables was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test, considering distributions normal when p > 0.05. For comparing groups based on quantitative variables with normal distributions, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied, presenting results as F-statistic values and corresponding p-values. In cases of non-normal distributions, the non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test was employed, with results expressed as H-statistic values and p-values. Comparisons of groups based on categorical variables were performed using the chi-squared test (χ²), reporting the χ² value and the significance level p.To assess the effect size when comparing groups on quantitative variables with a normal distribution (ANOVA), Cohen's d coefficient was calculated, where d ≈ 0.2 was interpreted as a small effect, d ≈ 0.5 as a medium effect, and d ≈ 0.8 as a large effect. For categorical variables (chi-squared test), Cramér's V coefficient was computed, with V < 0.1 indicating a negligible association, 0.1 ≤ V < 0.3 a weak association, 0.3 ≤ V < 0.5 a moderate association, and V ≥ 0.5 a strong association. In the case of quantitative variables with a non-normal distribution (Kruskal-Wallis test), the epsilon squared (ε²) coefficient was used to assess effect size, where ε² < 0.01 was interpreted as a negligible effect, 0.01 ≤ ε² < 0.04 as a weak effect, 0.04 ≤ ε² < 0.16 as a moderate effect, and ε² ≥ 0.16 as a strong effect.To analyze the primary efficacy parameter, repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed to assess the effects of time factors (pretest and posttest) and group factors (Group 1 and Group 2). Effect size was evaluated using partial eta-squared (η²).A survival analysis using the Cox proportional hazards model was conducted to assess the influence of multiple factors on the risk of relapse into alcohol dependence over one year. The model included 24 covariates encompassing demographic characteristics, history of alcohol use, family history, psychological factors, and treatment features.Validation of the model's assumptions included assessing the proportionality of hazards using scaled Schoenfeld residual plots, analyzing outliers with dfbeta residuals, and checking the linearity of the relationship between the logarithm of the hazard function and numerical covariates using Martingale residuals.For visualization of the results, Kaplan-Meier survival curves were constructed for each categorical variable. The statistical significance level for all tests was set at α = 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using statistical software.

3. Research Results and Their Discussion

3.1. Sample

- The study included 153 participants divided into two groups: Group 1 (n = 76) and Group 2 (n = 77). Overall, statistical analysis revealed no significant differences between the groups on the main sociodemographic characteristics, indicating the homogeneity of the sample and allowing further comparisons between groups without considering these factors as potential confounders.The gender composition of the sample was predominantly male (83.01%) with a small proportion of females (16.99%). The ethnic composition of the sample was diverse, with a predominance of Uzbeks (32.24%) and Russians (31.58%). The majority of participants (54.25%) identified themselves as Muslims and 30.07% as Orthodox Christians. The majority of participants (64.05%) grew up in complete families. At the time of the study, participants' marital status varied: 36.60% were married, 28.10% were not married/married, and 10.46% were divorced. 45.10% of the participants had a specialized secondary education, 22.22% had a higher education, and 15.03% had a high school education. More than half of the participants (56.86%) were working at the time of the study. About one third 32.03% had committed administrative offenses and 5.23% had committed criminal offenses. At the time of entry into the study, the mean MGAA scale score was 125.399 (SD = 17.423), with no statistically significant differences between groups (F = 0.424, p = 0.516, d = 0.105).

3.2. Primary Efficacy Endpoint

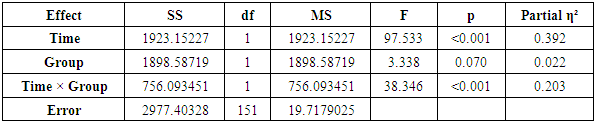

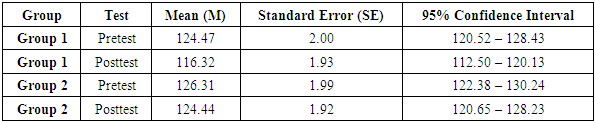

- In the conducted study, repeated measures analysis of variance (RM-ANOVA) was used to assess the effect of time (Pretest and Post-test) and group membership (Group 1 and Group 2) on MGAA indicators. The results of the statistical analysis are presented in Table 1.

|

|

| Figure 1. Dynamics of Changes in MGAA Scores in Group 1 and Group 2 Pretest and Posttest |

|

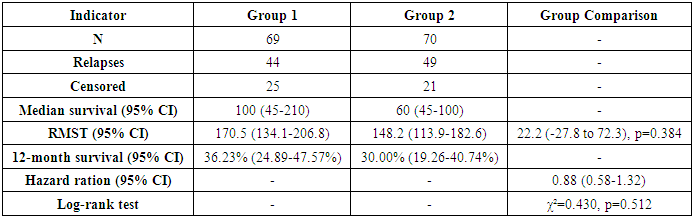

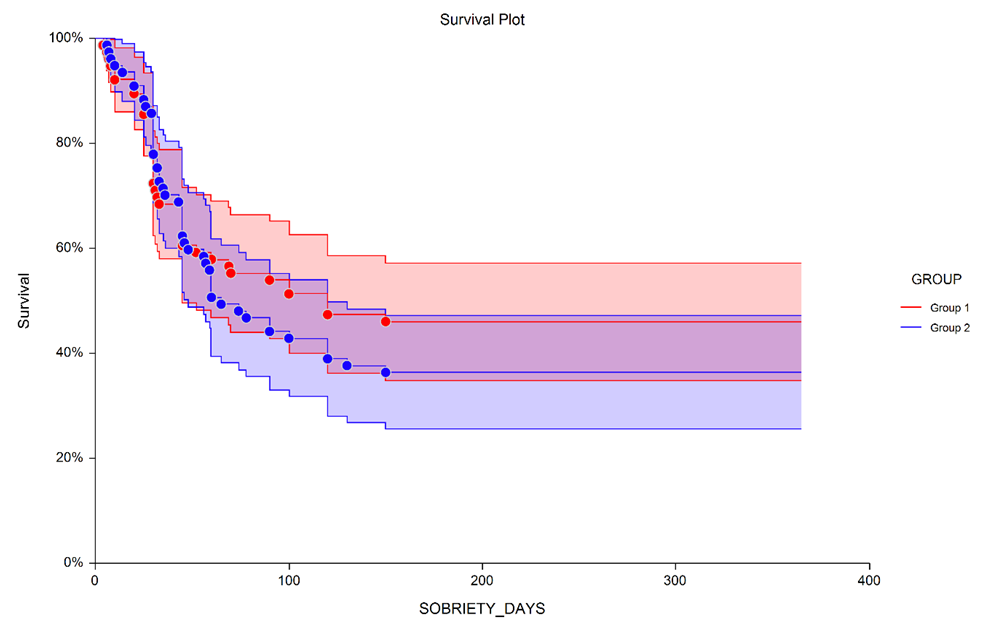

| Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier survival plot of 1-Year sobriety by group (Note: Missing values were treated as relapses.) |

4. Discussion

- The results of our study demonstrate a significant decrease in scores on the McMullan-Gilhar Addictive Attitudes (MGAA) Test over time, as indicated by the significant main effect of time. This suggests that participants, on average, exhibited a reduction in addictive attitudes during the study period. Notably, there was a statistically significant greater reduction in the total MGAA score in Group 1 compared to Group 2, with an effect size of ηp² = 0.203. This medium effect size indicates a modest superiority of the specific intervention implemented in Group 1 over the standard treatment in Group 2, potentially pointing to the effectiveness of our programme in modifying addictive attitudes in the short term.By specifically targeting addictive attitudes through our intervention programme, we aimed to enhance treatment adherence and, ultimately, clinical outcomes. The significant reduction in MGAA scores in the experimental group supports the hypothesis that modifying addictive attitudes can be an effective component of treatment strategies for alcohol dependence. However, despite the improvement in MGAA scores, the survival analysis over a one-year follow-up did not reveal a statistically significant difference in relapse rates between the two groups. Although Group 1 exhibited a slightly longer median survival time and higher 12-month survival probability compared to Group 2, these differences were not statistically significant. The hazard ratio also indicated only a slight, non-significant reduction in the risk of relapse for Group 1.Several factors might explain the lack of significant difference in relapse rates. First, external factors not controlled for in the study, such as environmental stressors, social support, and comorbid mental health conditions, may have influenced relapse rates. Second, socioeconomic factors like unemployment, financial problem may have influenced relapse rates independently of the intervention. Third, despite efforts to standardize the intervention delivery, subtle differences in patient-therapist interactions, patient engagement, or individual responses to the intervention could have impacted its effectiveness.The Cox proportional hazards model did not achieve overall statistical significance, indicating that the variables included did not collectively predict relapse risk effectively. However, certain individual factors were significantly associated with relapse. Morning alcohol consumption was linked to an increased risk of relapse, suggesting that individuals with more severe dependence are at higher risk. Initiation of regular alcohol use after the age of 30 was associated with a reduced risk of relapse, possibly reflecting differences in drinking patterns or life circumstances. Being raised in a single-parent family increased relapse risk, highlighting the potential impact of family structure on long-term outcomes. Additionally, unsuccessful attempts to control alcohol use were associated with a markedly increased risk of relapse, underscoring the challenges faced by individuals with a history of failed cessation attempts.These findings emphasize the complexity of treating alcohol dependence and the multifaceted nature of relapse. While modifying addictive attitudes is important, it may not be sufficient on its own to prevent relapse. Comprehensive treatment approaches that also address behavioral, environmental, and psychological factors are likely necessary to improve long-term outcomes.

5. Limitations

- This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. Although the single-blind design ensured that participants were unaware of their group assignments, the therapists delivering the intervention were not blinded. This lack of blinding on the part of the therapists could introduce performance bias, as their knowledge of the participants' group assignments might have unconsciously influenced their interactions and the delivery of the intervention.A significant limitation is the selection of sobriety as the primary outcome measure, without incorporating other important indicators such as quality of life, psychosocial functioning, or mental health status. Focusing solely on sobriety provides a narrow view of recovery and may not capture the full spectrum of benefits or challenges experienced by individuals undergoing treatment for alcohol dependence.The sample was drawn exclusively from inpatient treatment facilities in Uzbekistan, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other settings or populations. Cultural factors, healthcare infrastructure, societal attitudes towards alcohol use, and availability of support systems can vary significantly between countries, potentially influencing treatment outcomes differently.External factors not controlled for in the study, such as environmental stressors, social support networks, employment status, and comorbid mental health conditions, may have influenced relapse rates. These confounding variables could have impacted the effectiveness of the intervention and the overall outcomes, suggesting the need for a more comprehensive approach in future studies.

6. Conclusions

- This study set out to evaluate the effectiveness of a targeted intervention programme designed to modify addictive attitudes among individuals with alcohol dependence. The results demonstrated that the experimental group experienced a significant reduction in scores on the McMullan-Gilhar Addictive Attitudes Test compared to the control group, indicating that such interventions can effectively alter addictive attitudes in the short term.However, this positive change in attitudes did not translate into a statistically significant reduction in relapse rates over a one-year follow-up period. Although there was a trend towards longer median survival times and higher 12-month sobriety rates in the experimental group, these differences were not significant. This suggests that while modifying addictive attitudes is important, it may not be sufficient on its own to produce sustained behavioural change and prevent relapse.These findings highlight the multifaceted nature of alcohol dependence and the complexity of achieving long-term recovery. Effective treatment likely requires a comprehensive approach that addresses not only cognitive and attitudinal factors but also behavioural skills, environmental influences, social support networks, and psychological well-being. The choice of sobriety as the sole outcome measure may have limited the ability to detect other meaningful benefits of the intervention, such as improvements in quality of life or psychosocial functioning.In summary, while the intervention programme effectively modified addictive attitudes in the experimental group, this did not lead to a significant reduction in relapse rates over one year. These results suggest that modifying addictive attitudes is a valuable component of treatment but should be part of a more comprehensive, multifaceted approach to support long-term recovery in individuals with alcohol dependence. Continued research and development of integrated treatment strategies are essential to enhance outcomes and address the complex challenges associated with alcohol dependence.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML