-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2024; 14(10): 2466-2471

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20241410.04

Received: Sep. 17, 2024; Accepted: Sep. 28, 2024; Published: Oct. 12, 2024

Role of Extracorporeal Shock Wave Lithotripsy (SWL) Performed in Anesthetic High-Risk Patients Initially Presented with Urosepsis: Alternative or Compromising Modality

M. Rashidov, S. Eredjepov, R. Akhmedov, J. Alidjanov, J. Tursunkulov

Republican Research Center of Emergency Medicine, “Estimed” Private Clinics, Uzbekistan

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The aim of study was to analyze the role of Shock wave lithotripsy performed in anesthetic high-risk patients initially presented with urosepsis who were performed percutaneous nephrostomy. Background. After urinary tract infections and pathologic conditions of the prostate, urolithiasis is the third most common disease of the urinary tract, with an estimated prevalence of 2–3% and a life time recurrence rate of approximately 50%. Urosepsis is defined as sepsis caused by a urogenital tract infection. Urosepsis in adults accounts for approximately 25% of all sepsis cases. Material and methods. Between August 2013 and August 2016 1811 patients with urolithiasis were observed at the Republican Research Center of Emergency Medicine and “Estimed” private clinics. Elderly stone formers (age > 60 years) were under special observation. Results. Anesthesiological risk according to the ASA scale of all the patients was higher than 3. There was a wide range of comorbidities with clinical relevance to the management of stone disease. Discussion. Elderly stone formers (age >65 years) comprise 9.6–12% of all stone patients and usually experience the first symptomatic stone-related episode later in life. There are many interventions for ureteral calculi, including extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy, percutaneous nephrolithotomy and active surveillance. In many cases, shock wave lithotripsy is preferable for upper urinary tract calculi. Recent guidelines recommend that for all renal calculi except those in the lower pole, shock wave lithotripsy is recommended for not only calculi that are <10mm but also those measuring 10-20mm. Shock wave lithotripsy is also recommended for proximal ureter calculi, even for calculi >10mm. Conclusion. Shock wave lithotripsy is a treatment modality without necessity in anaesthesia unlike endoscopic modalities. More over, the advantage of SWL is possibility to repeat the session if first one was not successful.

Keywords: Shock wave lithotripsy, Urosepsis, Urolithiasis

Cite this paper: M. Rashidov, S. Eredjepov, R. Akhmedov, J. Alidjanov, J. Tursunkulov, Role of Extracorporeal Shock Wave Lithotripsy (SWL) Performed in Anesthetic High-Risk Patients Initially Presented with Urosepsis: Alternative or Compromising Modality, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 14 No. 10, 2024, pp. 2466-2471. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20241410.04.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The prevalence of urolithiasis varies from 5% to 20% and depends on age, sex, race and area of residence [1]. The risk of urolithiasis is higher in the western hemisphere (5-9% in Europe, 12% in Canada, 13-15% in the USA) than in the Eastern hemisphere (1-5%) where Uzbekistan is placed [2]. Age distribution of urinary stones are different. For example, in Italy, 65 – 74 years age group had the highest prevalence of urolithiasis (6.7%). In the United Kingdom, the prevalence is high in younger age group (15 – 59 years) than in the United States where prevalence remained constant over a 10-year period at 49 years [4]. In Korea the highest incidence occurred in 60 – 69 years age group [5].After urinary tract infections and pathologic conditions of the prostate [1], urolithiasis is the third most common disease of the urinary tract, with an estimated prevalence of 2–3% and a life time recurrence rate of approximately 50% [6]. Very often ureteral stones are complicated with infected ureterohydronephrosis and, in this situation, patients need care in status of urosepsis. Urosepsis is defined as sepsis caused by a urogenital tract infection. Urosepsis in adults accounts for approximately 25% of all sepsis cases [7]. Severe sepsis and septic shock is a critical condition, with a reported mortality rate ranging from 20% to 40% [7,8]. Urosepsis is mainly caused by urinary tract infection complicated by obstruction, with urolithiasis being the most common cause [7,8]. An early diagnosis is imperative for better clinical outcome. Emergent decompression of the collecting system is the standard of care for the initial management of urosepsis associated with obstructive urolithiasis. Both retrograde internal ureteral stent placement and percutaneous nephrostomy (PCN) drainage appear equally effective [9,10,11,12]. In elderly and multimorbid patients urosepsis is a particularly serious condition with a high rates of mortality. After adequate decompression of the renal collecting system and proper treatment with antibiotics, definitive management of the stone is needed. It also should be noted that in elderly patients urolithiasis linked with systemic diseases. This fact is described in several epidemiological studies, including coronary heart disease (CHD), hypertension [17,18], diabetes [19,20], atherosclerosis [21] and metabolic syndrome [22]. Whether a secondary therapy for an underlying stone disease after initial sepsis treatment improves the prognosis of these patients has not been systematically investigated. Patients with ureteral stones or smaller intrarenal stone burden are likely to be amenable to definitive treatment with ureteroscopy (URS). However, there is not so much data about possible application of extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (SWL) at aged high anesthesiological risk patients with previously placed nephrostomy drainage in order to avoid possible intraoperative complications. The aim of this study is to assess the possibility of SWL application at patients with nephrostomy drainage and high ASA score. The aim of study was to analyze the role of SWL performed in anesthetic high-risk patients initially presented with urosepsis who were performed percutaneous nephrostomy (PCN).

2. Material and Methods

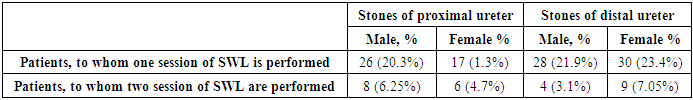

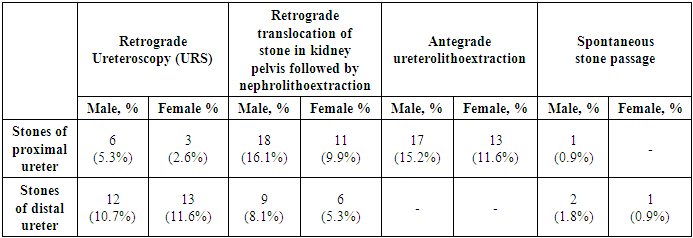

- Between August 2013 and August 2016 1811 patients with urolithiasis were observed at the Republican Research Center of Emergency Medicine and “Estimed” private clinics. Elderly stone formers (age > 60 years) were under special observation. The main purpose of the current study was to compare effectiveness of SWL (Group A) and endoscopic removal (control Group B) of ureteral stones at patients older than 60 years with severe comorbidities to whom PCN were previously performed due to ureteral stones complicated with urosepsis. All the patients had urosepsis by international classification [29].Inclusion criteria were as follows:- The patient's age over 60 years;- Clinically confirmed the presence of the stone of the proximal or distal ureter complicated with urosepsis;- Percutaneous nephrostomy was previously performed;- The presence of comorbidity, which explains the high anesthetic risk patient.The criteria for comparison of the both groups were as follows:- Achievement of 100% stone free;- The percentage of intra- and postoperative complications;- Duration of patients’ hospitalization;- Cost-effectiveness.Electronic database was created in aim of registering of observed patients. Registration and analysis of patients’ demographic variables, specifications of procedures, complications of procedure and the necessary for additional interventions were registered and analyzed.The presence of ureteral stone was confirmed by multispiral native CT. Pre-procedural percutaneous nephrostomy was guided by the presence of appropriate clinical indications. Patients of both groups considered as high medical risk (American Society of Anesthesiology, ASA, score ≥ 3). All patients in Group A were treated on the Huikang SWL-V®™(China) machine. The absence of urinary infection was confirmed before the procedure by a negative urine dipstick test. Single shot of Ceftriaxone 1.0 gram was administered intramuscularly before the procedure. Patients receiving oral anticoagulants were admitted before the SWL sessions, to achieve adequate preoperative optimization of their cardiovascular status and their clotting parameters. Patients with renal and proximal ureteric stones were placed supine, while prone positioning was necessary for distal ureteric stones. Shock waves were administered under fluoroscopic guidance at a rate of 90 shocks/min according to SWL protocol. Minimal power of shock waves, according to the manufacturer's guidance, was 13 kV, followed by gradual increase up to 16 kV. Maximum number of shocks during session was 5000. Patients were observed during next 4 h after procedure and were discharged if clinically stable.Subsequently, the patient was urged to observe and record the days of calculus fragments discharge of. Control visit was carried out 7 days after the procedure. During the control visit made kidney and bladder ultrasound and antegrade pyeloureterography were performed in order to confirm purity and ureteral patency with subsequent removal of nephrostomy drainage. In the case of calculus fragments presence or bad calculus fragmentation due to its high density SWL procedure was repeated. Patients to who SWL was repeated were admitted for the next follow-up visit in the next 7 days. During the second follow-up visit kidney and bladder ultrasound and antegrade pyeloureterography in order to confirm purity and ureteral patency were performed again.Final inspection was carried out after 2 months to register the possible remote complications of SWL.In group B, patients of Group B were in the same age category with the same high anesthetic risk. Percutaneous nephrostomy also was performed pre-procedural due to presence of proximal or distal ureteral stone complicated with urosepsis. Stone removal was performed by endoscopic approach - retrograde ureteroscopy, retrograde translocation of stone in kidney pelvis followed by nephrolithoextraction or antegrade ureterolithoextraction.Statistical processing was performed using Student's t-test.

3. Results

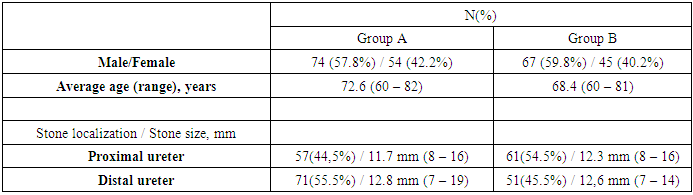

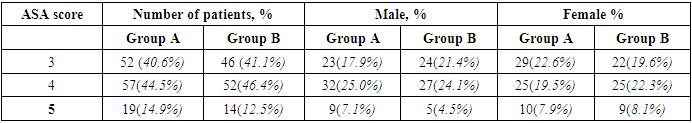

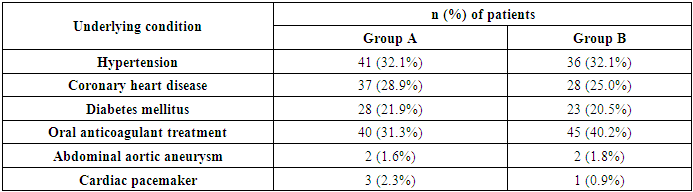

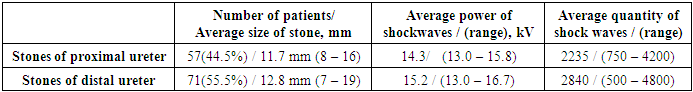

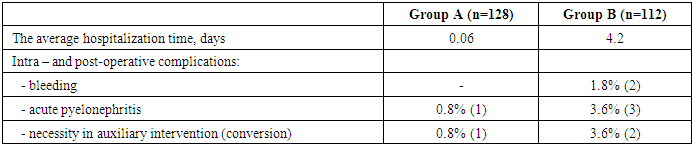

- Group A consisted of 128 patients as well as Group B consisted of 112 patients. Demographic and clinical data of patients in both groups are shown in Table 1.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

- Urolithiasis is mainly considered a disease of middle age and only a few reports focus on the epidemiology of this common entity in the geriatric population. Elderly patients are defined as 65 years old according to the definitions of the World Health Organization (WHO) [22]. Elderly stone formers (age >65 years) comprise 9.6–12% of all stone patients [24,25] and usually experience the first symptomatic stone-related episode later in life [24]. There are many interventions for ureteral calculi, including extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (SWL), URS lithotripsy, percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PCNL), and active surveillance [26,27,28]. However, there are no standardized treatments for elderly patients with ureteral calculi. In many cases, SWL is preferable for upper urinary tract calculi. Recent guidelines recommend that for all renal calculi except those in the lower pole, SWL is recommended for not only calculi that are <10mm but also those measuring 10-20mm. SWL is also recommended for proximal ureter calculi, even for calculi >10mm [26,27].Often, ureteral stones at elderly patients due to concomitant pathology and immune status are complicated by urinary tract infections up to urosepsis. Adequate drainage by ureteral stenting or percutaneous nephrostomy is way of urosepsis managing. After the elimination of sepsis manifestations there is a question about how to remove ureteral stone being the main cause of disease.In our study, we decided to compare the results of SWL and endoscopic stone removal of the proximal and distal ureter at elderly patients after revealing the manifestations of urosepsis with previously placed nephrostomic drainage. The challenge of further management tactic depends on possible risk of anesthesia during intervention, intra- and postoperative complications. As can be seen from the results, SWL may be widely used in elderly patients with a high anesthesiologic risk. One major drawback in this comparison is the time during which a patient must “bear” nephrostomy drainage. However, this fact can be countered versus economic costs. SWL related spending are definitely cheaper than endoscopic removal. The limitations of our study are that it was a retrospective, observational study and a relatively short follow-up period can evaluate neither the long-term recurrence rate of stones nor the symptom-free and disease-free survival. Despite these limitations, our study suggests that SWL lithotripsy may be a standard treatment for proximal and distal ureteral in elderly patients with nephrostomic drainage aged 65 years or more.

5. Conclusions

- SWL has a similar incidence of postoperative pyelonephritis and similar stone free rate (SFR) as endoscopic approach in patients older than 65 years of age, but low risk of intraoperative comorbidity related complications. SWL is a treatment modality without necessity in anaesthesia unlike endoscopic modalities. Anaesthesia for multimorbid patients with ASA =>3 has corresponding risks. More over, the advantage of SWL is possibility to repeat the session if first one was not successful. To perform repeat endoscopic procedure by elderly people is more complicate. Thus, SWL is one of the best treatments for proximal and distal ureteral in elderly patients with nephrostomic drainage even in elderly patients.

Conflict of Interests

- The authors declare no conflict of interest. This study does not include the involvement of any budgetary, grant or other funds. The article is published for the first time and is part of a scientific work.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

- The authors express their gratitude to the management of the multidisciplinary clinic of Tashkent Medical Academy for the material provided for our study.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML