-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2024; 14(9): 2237-2241

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20241409.23

Received: Aug. 28, 2024; Accepted: Sep. 13, 2024; Published: Sep. 18, 2024

Pregnancy and Lactation-Associated Osteoporosis: A Case Report

Alikhanova N. M.1, Abboskhujaeva L. S.2

1Center for Health and Strategic Development, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

2Republican Specialized Scientific and Practical Medical Center for Endocrinology named after Academician Y.Kh. Turakulova, Tashkent, the Republic of Uzbekistan

Correspondence to: Abboskhujaeva L. S., Republican Specialized Scientific and Practical Medical Center for Endocrinology named after Academician Y.Kh. Turakulova, Tashkent, the Republic of Uzbekistan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Pregnancy and lactation-associated osteoporosis (PLO) is a rare but severe form of premenopausal osteoporosis, occurring predominantly during the last trimester of pregnancy or the first months postpartum. Purpose of the Study: In this study, we report a case of osteoporosis associated with pregnancy and lactation. Materials and Methods: Laboratory biochemical studies included: determination of total calcium, phosphorus, vitamin D, alkaline phosphatase, parathyroid hormone (PTH), creatinine, ALT, and AST levels in the blood, as well as biochemical markers of bone remodeling - β-CrossLaps, NTx (N-telopeptide), osteocalcin, OPG, RANKL, P1CP, hormone D, and calcitonin (determined using an automatic ELECSYS analyzer through electrochemiluminescent analysis and ELECSYS kits). Results: PLO is a rare clinical condition and should be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients with lower back pain during or after pregnancy. Although not listed as a diagnostic criterion, excluding other causes of osteoporosis and understanding the progressive clinical course is necessary and beneficial in the diagnostic process. At the same time, monitoring and assessing the effectiveness of PLO intervention is also very important.

Keywords: Fractures, Compression, Osteoporosis, Pregnancy

Cite this paper: Alikhanova N. M., Abboskhujaeva L. S., Pregnancy and Lactation-Associated Osteoporosis: A Case Report, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 14 No. 9, 2024, pp. 2237-2241. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20241409.23.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Pregnancy and lactation-associated osteoporosis (PLO) is a rare but severe form of premenopausal osteoporosis, occurring predominantly during the last trimester of pregnancy or the first months postpartum. Preliminary estimates indicate an incidence of 4-8 cases per 1,000,000 women, though this rate may be higher as PLO often remains undiagnosed [1,2,3].The most common symptom of PLO is acute lower back pain due to bone marrow edema and vertebral fractures. MRI reveals multiple vertebral fractures (VF) and, less commonly, various types of hip joint involvement [3,4,5]. Pregnancy, childbirth, and lactation cause a series of changes in calcium metabolism and bone tissue. Disruptions in calcium metabolism can trigger the development of osteopenia or osteoporosis in the absence of adequate treatment [6,7,8]. In Uzbekistan, research concerning pregnancy and lactation-associated osteoporosis has not been conducted previously.

2. Purpose of the Study

- In this study, we report a case of osteoporosis associated with pregnancy and lactation.

3. Materials and Methods

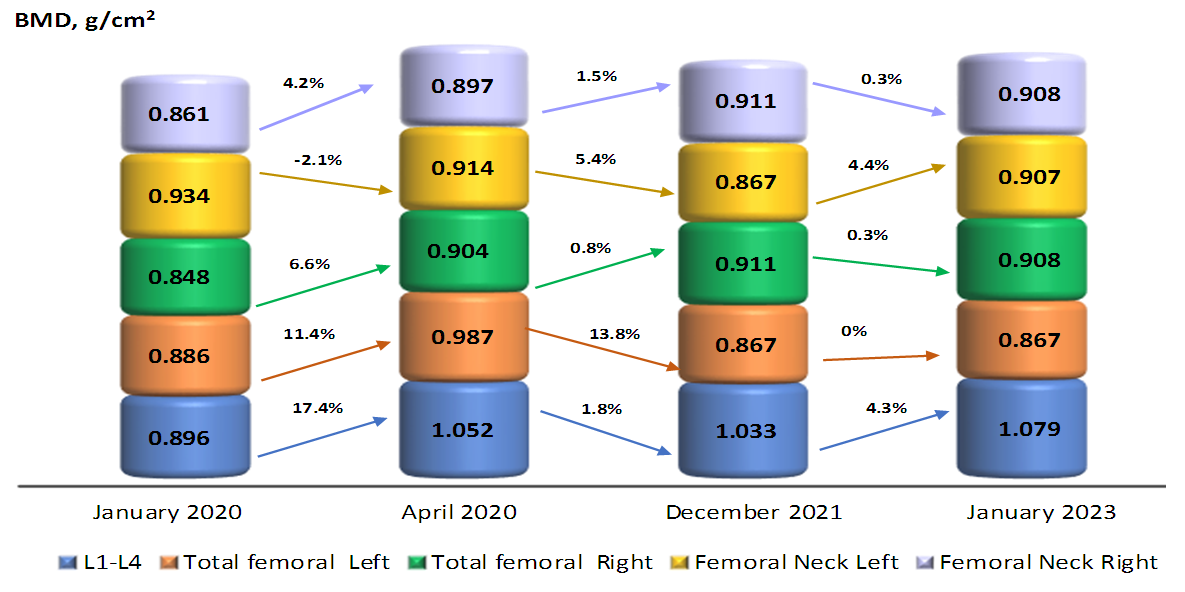

- Laboratory biochemical studies included: determination of total calcium, phosphorus, vitamin D, alkaline phosphatase, parathyroid hormone (PTH), creatinine, ALT, and AST levels in the blood, as well as biochemical markers of bone remodeling - β-CrossLaps, NTx (N-telopeptide), osteocalcin, OPG, RANKL, P1CP, hormone D, and calcitonin (determined using an automatic ELECSYS analyzer through electrochemiluminescent analysis and ELECSYS kits).Bone mineral density was assessed by dual-energy absorptiometry (DEXA) using the Prodigy bone densitometer by GE Lunar Corporation, USA. This study evaluated the effectiveness of the treatment being conducted.The measurement results were expressed in absolute values of BMD (bone mineral density - g/cm²) and as a T-score, according to the WHO's generally accepted criteria for diagnosing osteoporosis. Measurements were taken in two standard skeletal regions: the lumbar spine (first four vertebrae L1-L4) and the proximal femur. In interpreting the data for osteoporosis diagnosis of the spine, the Total indicator is assessed in standard deviation units. For evaluating the increase in BMD against the background of osteoporosis pharmacotherapy, the absolute BMD indicator reflecting bone mineral density was used.

4. Results

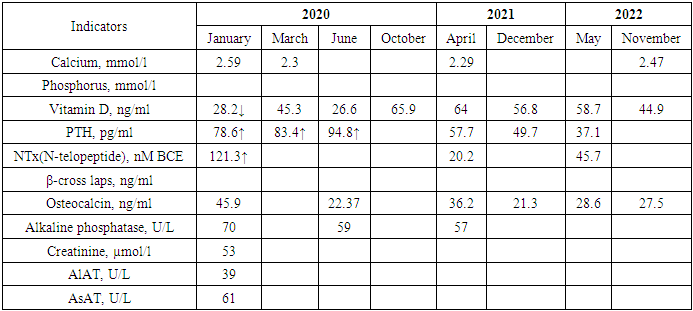

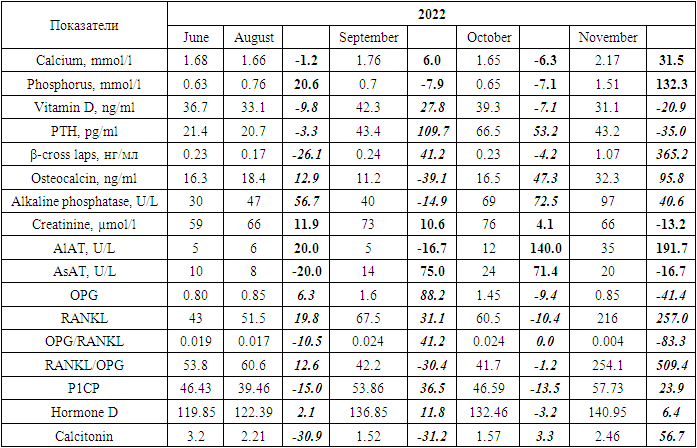

- The first pregnancy occurred at the age of 22. During pregnancy, there was no toxicosis. The delivery was natural at 37-38 weeks of pregnancy. Breastfeeding duration was 3 months. A 23-year-old woman presented with complaints of moderate back pain, which began in the last trimester of pregnancy. A week after delivery, the back pain intensified, interfering with childcare and daily activities. Two months postpartum, the patient consulted an orthopedic surgeon, who referred her for an MRI of the lumbosacral spine. The MRI conclusion indicated signs of a compression fracture of the Th2 vertebral body. The patient was recommended to consult an endocrinologist.Laboratory tests, including measurements of calcium, phosphorus, vitamin D, parathyroid hormone, N-telopeptide, β-cross laps, osteocalcin, alkaline phosphatase, creatinine, and liver enzymes, revealed a vitamin D deficiency and elevated levels of N-telopeptide, as well as a tendency toward increased PTH levels over a 4-month period (Table 1).

|

|

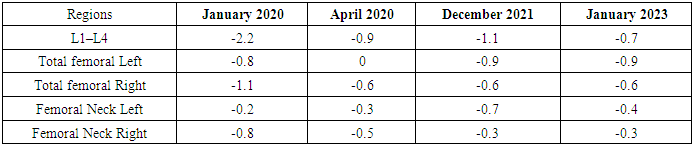

| Figure 1. Dynamics of BMD changes and percentage of increase |

|

5. Discussion

- Pregnancy and lactation-associated osteoporosis (PLO) is a rare condition characterized by fractures occurring in late pregnancy or the postpartum period. Its etiology is undetermined, and its treatment and natural course are poorly understood. Although the exact cause remains unclear, risk factors have been identified, including having first-degree relatives with PLO, low BMI, physical inactivity, poor nutrition, insufficient calcium intake, and smoking [9].Pregnancy and breastfeeding lead to temporary bone loss because calcium is transferred from the mother to build the skeleton of the fetus and infant [7,10]. PLO is characterized by high bone turnover, initially manifesting as a loss of trabecular bone, where the bone surface area to volume ratio is greatest [10].Back pain resulting from vertebral fractures can be acute or chronic. Early diagnosis and treatment are crucial to prevent further fractures and chronic pain, as well as to optimize bone structure [11]. PLO is more common during the first pregnancy than in subsequent pregnancies [12].The goal of treatment was to improve bone mineral density to a level that would allow the patient to undergo another pregnancy and subsequently breastfeed with minimal risk of new vertebral fractures. Interdisciplinary monitoring was important to ensure rapid treatment and recovery to normal activity levels.There is no universally agreed-upon opinion or guideline for treating this condition. Treatment options are limited to those practiced in documented cases. Most cases recommend cessation of breastfeeding [13,14]. Other options include calcium and vitamin D supplementation [15], bisphosphonates [9], teriparatide [16], strontium ranelate [17], and kyphoplasty for treating postpartum vertebral fractures [18].Thus, PLO is associated with significant morbidity, a high prevalence of recognized osteoporosis risk factors, and a risk of recurrence in subsequent pregnancies. Bisphosphonate therapy, administered shortly after the onset of symptoms, significantly increases spinal bone density in patients with PLO [9].It is crucial to monitor and evaluate the effectiveness of treatment, which determines the success or failure in managing PLO. In our case, with regular follow-up, education, and monitoring, the patient was able to achieve a normal level of 25(OH)D3. During follow-up, attention should be given to assessing new fractures both clinically and visually. Since vertebral fractures differ from hip and forearm fractures, which often occur without clinical symptoms and with a clear history of falls, they are easily missed during diagnosis. Therefore, spinal imaging is an effective method for detecting new fractures during follow-up.

6. Conclusions

- PLO is a rare clinical condition and should be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients with lower back pain during or after pregnancy. Although not listed as a diagnostic criterion, excluding other causes of osteoporosis and understanding the progressive clinical course is necessary and beneficial in the diagnostic process. At the same time, monitoring and assessing the effectiveness of PLO intervention is also very important.Fractures associated with PLO can be a significant cause of long-term disability. Early diagnosis and treatment with calcium and vitamin D, as well as regular monitoring of these cases, are particularly important for preventing fractures and improving the quality of life for patients.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML