-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2024; 14(8): 1966-1970

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20241408.03

Received: Jul. 13, 2024; Accepted: Jul. 30, 2024; Published: Aug. 2, 2024

Analysis of Eating Disorders Using the Dutch Questionnaire DEBQ in Young Obese Patients

Khaydarova Feruza Alimovna, Latipova Maftunakhon Abbos Qizi

Republican Specialized Scientific and Practical Medical Center of Endocrinology of the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Uzbekistan named after Academician. Y.H. Turakulova, Department of Clinical Endocrinology, Tashkent, Republic of Uzbekistan

Correspondence to: Khaydarova Feruza Alimovna, Republican Specialized Scientific and Practical Medical Center of Endocrinology of the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Uzbekistan named after Academician. Y.H. Turakulova, Department of Clinical Endocrinology, Tashkent, Republic of Uzbekistan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

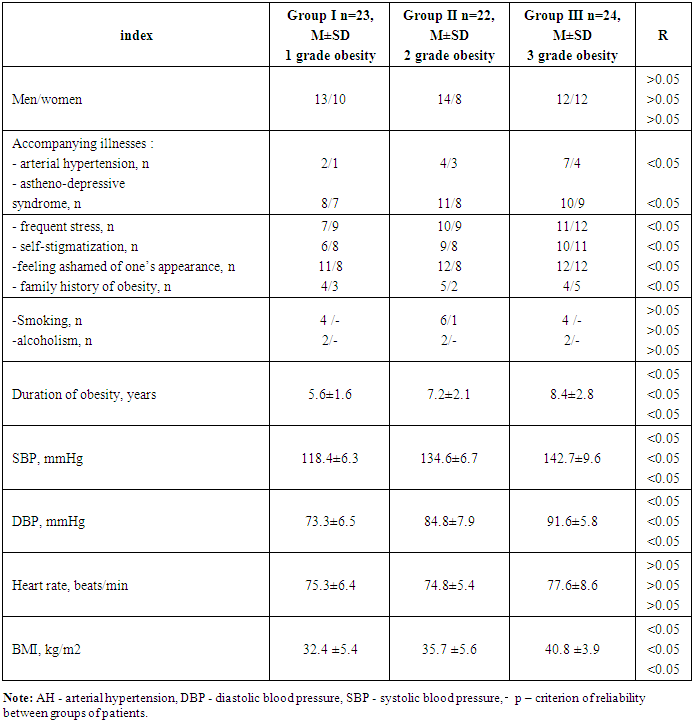

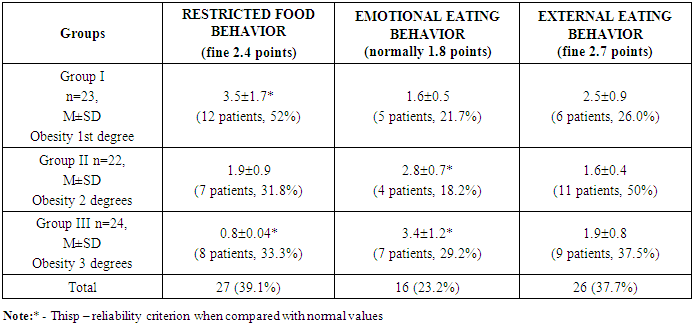

Purpose of the study - study the value of international questionnaires in assessing eating disorders in young obese individuals. Material and research methods. The study included 190 patients with grade 1-3 obesity. Of these, 69 patients were selected (30 women, 39 men, mean age 32.8±1.7 years) according to the study protocol. The control group consisted of 20 healthy individuals. Patients were divided into 3 groups depending on BMI: group I, n=23, BMI>= 30 AND < 35 kg/m2, group II, n=22, BMI>= 35 AND < 40 kg/m2, III group, n=24, BMI> 40 kg/m2. Blood tests were performed to assess blood biochemical parameters (ALT, AST, bilirubin, lipid spectrum, etc.) The study also used instrumental examination methods - ultrasound of internal organs, indicators of the quality of life of patients (Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnairea questionnaire developed by us), as well as statistical methods. Research results. From Table 3 it follows that in patients of group 1, in 52% of cases, DEBQ questionnaire scores were more likely to have restrictive eating disorder – more than 50% of observations (p < 0.05). In 2, external eating disorder was more common (50% of observations). In group 3 patients, external eating disorder was also more common (37.5%). In general, among the 69 selected individuals, restrictive eating disorders were more common -27 (39.1%). Conclusions. 1. Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ) is the most sensitive and informative for determining the quality of life and the presence of anxiety disorders in obese patients. 2. Assessment of quality of life by The questionnaire we developed can act as a preliminary questionnaire for screening patients with latent forms of eating disorder.

Keywords: Obesity, Eating disorders, DEBQ questionnaire

Cite this paper: Khaydarova Feruza Alimovna, Latipova Maftunakhon Abbos Qizi, Analysis of Eating Disorders Using the Dutch Questionnaire DEBQ in Young Obese Patients, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 14 No. 8, 2024, pp. 1966-1970. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20241408.03.

Article Outline

1. Background

- Eating in response to negative emotions (NE) may be a factor in the weight gain experienced by many dieters. Possible causes of NE include severe dietary restrictions, poor awareness of one's own needs, difficulty expressing oneself, dysregulation of emotions, and dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) stress axis. NE can also be the result of inadequate upbringing or depressive feelings in combination with a genetic predisposition. There is also strong evidence that NE mediates the relationship between depression and obesity.Additionally, calorie-restricted diets are known to be ineffective for overweight patients in the short term. Over the long term, most of the lost body weight is regained, and some patients even begin to weigh more than before the diet [1,2]. Chronic dieting, the tendency to restrict food intake to maintain or reduce body weight, has been shown repeatedly in population samples to even predict future weight gain [3].There are a number of studies that have shown the concept of emotional eating (eating in response to negative emotions or stress [4,5] as a possible explanatory factor for weight gain in many dieters.Eating disorders are mental health disorders combined with somatic and psychosocial diseases; only about 50% of patients achieve lifelong remission [6]. The DSM-5 identifies eight “eating and eating disorders” [7], however, the authors disproportionately study anorexia nervosa (AN) and, to a lesser extent, bulimia nervosa (BN) and binge eating disorder (BED).The worldwide lifetime prevalence of any eating disorder ranged from 0.74 to 2.2% in men and 2.58 to 8.4% in women. The estimated lifetime prevalence of eating disorders ranged from 2.58 to 8.4% among women and girls. [8,9]The etiology of eating disorders is complex but includes a genetic basis, and indeed, AN and BN exhibit a genetic diathesis [10]. Recently, a genome-wide association study identified eight significant loci for AN [11], and epigenetics has also been implicated in the etiology of eating disorder [12]. Other biological, social, cultural and psychological factors contribute to the etiology of eating disorders [13], and gut microbes modulate a variety of biological processes that influence the clinical manifestations of eating disorders, the details of which have been discussed in a number of studies.Additionally, weight-related stigma has significant adverse impacts on the lives, health, and treatment utilization of people with higher weights. Weight stigma can lead directly to eating disorders through complex neurobiological mechanisms or to reduce the emotional distress it causes. There is active research into the neurobiological mechanisms of weight stigma and its association with eating disorders [14–16]. Understanding and addressing weight stigma is critical to caring for higher weight individuals. Experiences of weight stigma, body shame, or other negative emotions such as guilt are traumatic and may contribute to and worsen eating disorders in people with eating disorders [17,18].Three types of eating disorders can be measured using the Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ [19]). Although eating styles can also be measured using other instruments (references in Barrada et al. [20]), the DEBQ was the first instrument to capture the three eating styles using unidimensional scales. The tool is widely cited (>2300 citations in Google Scholar) and translated into more than 15 languages (e.g. German [21], Chinese [22], Spanish [23]). The three scales have good reliability, dimension validity, and predictive validity, respectively, for stress-induced food intake [24,25], eating in response to food signals [26] and eating less food than you would like [27] and DEBQ. rated "adequate" or "good" by the Dutch Committee for Testing and Testing (COTAN) on all EFPA (European Federation of Psychological Associations) criteria (e.g. norms, reliability (internal consistency, test-retest) test) and validity (dimensional validity , construct validity and criterion validity) (COTAN, [28])).The DEBQ consists of three subscales that examine important aspects of problematic eating, namely emotional eating (food consumed due to negative emotional states), external eating (food consumed due to external circumstances regardless of internal hunger) and restrictive eating. nutrition (limiting calorie intake for weight loss). Inhibition theory suggests that chronic calorie restriction as a method of weight loss is unsustainable for many people and may eventually lead to disinhibited eating caused by external or internal stimuli.The DEBQ has been validated in Taiwan, Spain, Korea and Japan.The DEBQ consists of 20 items and assesses three types of eating behaviors [28]. The first is emotional eating and consists of seven items focusing on negative emotions, for example: “If you feel depressed, do you feel like eating?” The second type is external eating (six items), which asks whether food consumption is caused by external circumstances, for example: “Do you feel hungry when you see or taste good food?” Finally, restrained eating (seven items) refers to consciously restricting food intake to maintain or control weight, for example: “Have you ever tried to avoid eating after dinner to lose weight?” Items were rated using a point scale (never, rarely, sometimes, often, very often) on which scores ranged from 0 to 1b. High total scores for each eating behavior indicate greater support for that behavior.Purpose of the study - analyze eating disorders in 75 obese young people using the Dutch DEBQ questionnaire.

2. Material and Research Methods

- The study included 1098 patients (644 men and 454 women) with grade 1-3 obesity, examined in 4 pilot regions of the Republic of Uzbekistan: Tashkent, Samarkand, Jizzakh and Andijan regions. Of these, 600 patients (average age 32.8±1.7 years) were selected using a questionnaire developed by us, according to the study protocol. Next, out of 600 patients using a questionnaire DEBQ selected 195 young people with eating disorders and varying degrees of obesity, of whom 69 completed all studies. The control group consisted of 20 healthy individuals of the appropriate age (10 men and 10 women).Inclusion criteria: obesity grade 1-3, men and women, age from 18 to 35 years.Exclusion criteria: diabetes mellitus type 1 and 2, acute and chronic diseases of the kidneys, liver and heart, connective tissue diseases, vasculitis, cancer, children, adolescents, people over 44 years of age.At both baseline and follow-up assessments, weight (kg), height and waist circumference (cm), hip circumference (cm), neck circumference (cm) were measured on the same day and immediately before the psychological assessment.Blood tests were performed to evaluate levels of total cholesterol (and high-density lipoprotein (HDL) and low-density lipoprotein), triglycerides, alanine aminotransferase, glucose, and glycated hemoglobin. In addition, blood insulin levels were examined. Vital signs such as diastolic blood pressure and systolic blood pressure were also assessed. Statistical calculations were carried out in the Microsoft software environment Windows using the Microsoft Excel-2007 and Statistica version 6.0, 2003 software packages. The data obtained are reflected in the dissertation in the form M ± m, where M is the average value of the variation series, m is the standard error of the mean value. The significance of differences between independent samples was determined using the Mann-Whitney method.

3. Results of Own Research and Their Discussion

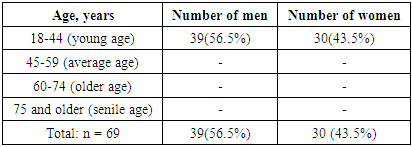

- Table 1 shows the distribution of examined patients by gender and age.

|

|

|

4. Conclusions

- 1. Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ) is the most sensitive and informative for determining the quality of life and the presence of anxiety disorders in obese patients. 2. Assessment of quality of life by The questionnaire we developed can act as a preliminary questionnaire for screening patients with latent forms of eating disorder.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML