-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2024; 14(7): 1940-1944

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20241407.44

Received: Jul. 4, 2024; Accepted: Jul. 22, 2024; Published: Jul. 26, 2024

Comprehensive Management of Gastroduodenal Bleeding and Pecularities of Gastroduodenal Lesions in Patients with Liver Cirrhosis

Salamov N. I., Urakov Sh. T., Abdurakhmanov M. M., Abdurakhmanov Z. M.

Department of Surgical Diseases and Intensive Care, Bukhara State Medical Institute, Bukhara, Uzbekistan

Correspondence to: Abdurakhmanov Z. M., Department of Surgical Diseases and Intensive Care, Bukhara State Medical Institute, Bukhara, Uzbekistan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

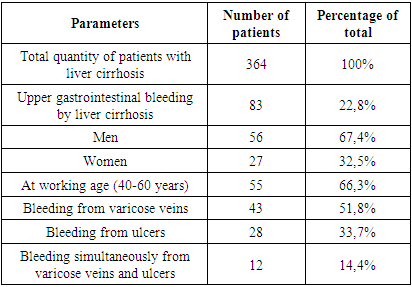

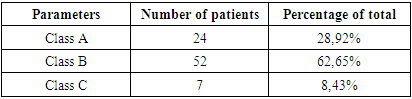

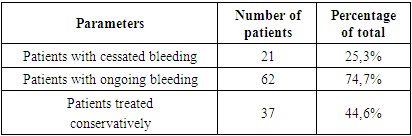

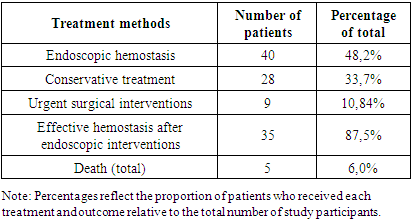

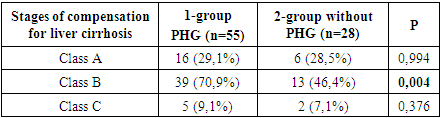

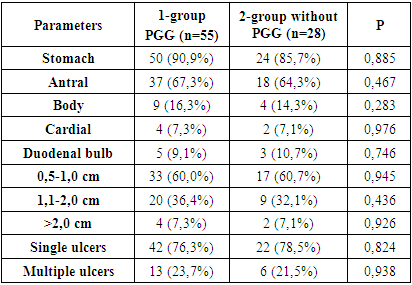

Clinical diagnosis of gastroduodenal erosions and ulcers in patients with liver cirrhosis is difficult due to the lack of unique symptoms and anamnestic data. Treatment of ulcer bleeding of patients with intrahepatic portal hypertension is still no solved sophisticated issue of the urgent surgery. Differentiated approach to the treatment of bleeding of the gastroduodenal zone could play the core role in this regard. Objective. To study treatment results for patients with bleeding from erosive and ulcerative lesions of the gastric and duodenal mucosa among patients with varicose veins of the esophagus and stomach and the features of erosive and ulcerative lesions of the gastroduodenal zone in patients with cirrhosis of the liver in combination with or without portal hypertensive gastropathy. Materials and methods. In the period from 2021 to 2023, 364 patients with suffering from cirrhosis of the liver, erosive and ulcerative lesions of the gastroduodenal zone, of whose 83 patients (23% of the total number of subjects) were included in the study who experienced bleeding from erosions and ulcers of the gastrointestinal tract and varicose veins of the esophagus and stomach. The study participants were divided into two groups: the patients with (n=55) and without portal hypertensive gastropathy (PHG) (n=28). Results. The age of the patients ranged from 25 to 75 years. In 28 patients (37,73%), the source of bleeding was ulcers of the stomach and duodenum, among which 7 cases related to the stomach and 21 to the duodenum. In the remaining 12 patients (14,4%), bleeding occurred simultaneously from varicose veins and gastroduodenal ulcers. 21 patients (25,3%) showed signs of cessated bleeding on admission, while 62 patients (74,7%) had ongoing bleeding. In 40 of these patients (48,2%), suffering from active bleeding, underwent endoscopic hemostasis, the goal of which was to stop bleeding from both varicose veins of the esophagus and stomach, and from gastroduodenal ulcers. Effective hemostasis was achieved in 35 cases (87,5%) and no death was observed. In cases where the source of bleeding was varicose veins of the esophagus and stomach, endoscopic sclerotherapy sessions were performed using a 3% solution of ethoxysclerol. 9 patients (10,8%) underwent emergency surgery. Of the group of patients who underwent urgent surgical interventions, 2 patients (22,2%) had recurrent bleeding from varicose veins of the esophagus and stomach, resulted in death due to worsening liver failure. In 28 patients (33,7%), bleeding was successfully stopped using conservative treatment methods. However, in this group, 3 patients had a fatal outcome due to acute hepatic-renal failure (10,7%). Patients with Child-Pugh class B liver cirrhosis was more likely to experience erosive and ulcerative lesions of the gastroduodenal zone compared to patients of the same class without PHG (p=0,004). There were no differences in the localization, the size and number of ulcers of the gastroduodenal zone and in the frequency of ulcerative bleeding in liver cirrhosis patients with PHG and without PHG (p>0,05). Conclusions. The choice of treatment tactics in patients with gastroduodenal bleeding requires an integrated approach. It is important to consider not only the intensity of bleeding and the degree of liver failure, but also to determine the presence of one or more sources of hemorrhage. This includes a detailed examination of all potential causes of bleeding and an individual approach to each case. No differences in the localization, the size and number of ulcers of the gastroduodenal zone and in the frequency of ulcerative bleeding in liver cirrhosis patients with PHG and without PHG highlight the importance of further study in this area.

Keywords: Portal hypertension, Liver cirrhosis, Bleeding, Portal hypertension gastropathy, Erosion and ulcer

Cite this paper: Salamov N. I., Urakov Sh. T., Abdurakhmanov M. M., Abdurakhmanov Z. M., Comprehensive Management of Gastroduodenal Bleeding and Pecularities of Gastroduodenal Lesions in Patients with Liver Cirrhosis, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 14 No. 7, 2024, pp. 1940-1944. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20241407.44.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- A complete understanding of the mechanisms of formation of erosions and ulcers in patients with cirrhosis of the liver remains the subject of research. There is only limited data on the features of gastroduodenal lesions in cirrhosis with portal gastropathy. The development of hepatogenic ulcers is associated with stagnation of blood in the gastroduodenal zone, changes in blood composition, a decrease in oxygen saturation of the tissues of the stomach and duodenum, leading to ischemia of their walls and acidemia, as well as, to a lesser extent, with acid-peptic factor [1,17]. Jean Auroux and others (2003) show the presence of gastroduodenal ulcers in 23,4% of patients [2], while Shafi F. et al. found gastroduodenal ulcers in 9,6% of patients with cirrhosis of the liver [14]. In recent studies, stomach ulcers in cirrhosis were more common in 27,3 % [19] and in 33% cases [18].A relationship was found between the frequency of ulcerative lesions and the stage of compensation for cirrhosis of the liver, especially in class B according to Child-Pugh [10]. Literature data showed that gastroduodenal ulcerative bleeding was observed in a wide range from 2% to more than 40% of patients with cirrhosis of the liver [12,13,15,16].In Uzbekistan, like other regions, there are differences in the quality of medical care when dealing with such cases. Traditionally used wait-and-see tactics based on conservative treatment often do not bring the desired results, which indicates the need to improve treatment approaches.The improvement of therapeutic results is possible through the integration and optimization of existing hemostasis methods and the development of comprehensive therapeutic programs, including timely surgical interventions and correction of impaired body functions.As part of an extensive study of ulcerative bleeding associated with cirrhosis of the liver, Kolosovych and his colleagues (2023) point out that erosions and ulcers in the upper gastrointestinal tract are often the result of exposure to cirrhosis of the liver, although it was previously thought that they could be manifestations of portal hypertension [11]. In the context of this issue, it is important to note that the frequency of ulcerative lesions of the gastroduodenal zone does not demonstrate a direct connection with Helicobacter pylori infection [4,7]. However, alcohol consumption, as studies have shown, significantly increases the risk of developing such gastroduodenal erosions [7].In general, research in this area highlights the difficulty of diagnosing and choosing therapeutic tactics for ulcerative bleeding in patients with cirrhosis of the liver [8,12]. The treatment approach should take into account not only the features of cirrhosis, but also possible complications associated with it, such as ulcerative lesions of the stomach and duodenum [3]. This requires a comprehensive approach, including both drug treatment and, if necessary, surgical intervention, especially in situations of severe disease. Thus, the characteristics of erosive and ulcerative lesions of the gastroduodenal zone in patients with cirrhosis of the liver, especially in the context of ulcerative bleeding, are still insufficiently studied [9]. In particular, there are few such studies in the Republic of Uzbekistan.

2. Materials and Methods

- The study, conducted from 2021 to 2023 in the surgical department of the Bukhara branch of the Republican Scientific Center for Emergency Medical Care, included 364 patients with cirrhosis of the liver. Upon admission, to assess the condition of the mucous membrane of the esophagus, stomach and duodenum in all patients, oesophagogastroduodenoscopy was performed according to a standard technique using the “FUJINON” device (Japan). During the examination, the localization of erosive and ulcerative lesions, the size of ulcers and the intensity of bleeding from them were evaluated, classifying them according to the classification of J.A. Forrest [7]. The severity of portal hypertensive gastropathy (PHG) was assessed according to the criteria of Baveno III [6]. The Child-Pugh classification was used to determine the stage of compensation for cirrhosis of the liver [5]. The study participants were divided into two groups: the patients with and without PHG (comparison group). The analysis of the collected data was carried out using the SPSS 22.0 statistical package. To test statistical hypotheses, a criterion with a critical significance level of p<0,05 was used.

3. Results and Discussion

- Of the 364 patients diagnosed with liver cirrhosis, 83 patients (approximately 23%) had bleeding from erosive ulcerative lesions of the stomach and duodenum, who were included in this study. The age group of these patients ranged from 25 to 75 years, while the majority of them 55 (66,37%) were of working age, that is, in the range from 40 to 60 years. Men made up the majority of this group (67,47%, or 56 patients), while there were 27 women (32,53%).43 of these patients (51,8%) suffered from bleeding caused by varicose veins of the esophagus and stomach. In 28 patients (37,7%), the source of bleeding was ulcers of the stomach and duodenum, among which 7 cases related to the stomach and 21 to the duodenum. In the remaining 12 patients (14,4%), bleeding occurred simultaneously from varicose veins and gastroduodenal ulcers (Table 1).

|

|

|

|

|

|

4. Conclusions

- Based on extensive research, the following key aspects can be identified regarding the diagnosis and treatment of patients with erosive and ulcerative lesions of the stomach and duodenum against the background of liver cirrhosis.The incidence of gastric and duodenal ulcers in patients with liver cirrhosis is approximately 22,8%. This figure is consistent with the results obtained in other studies, highlighting the prevalence of this pathology in this category of patients.The choice of treatment tactics in patients with gastroduodenal bleeding requires an integrated approach. It is important to consider not only the intensity of bleeding and the degree of liver failure, but also to determine the presence of one or more sources of hemorrhage. This includes a detailed examination of all potential causes of bleeding and an individual approach to each case.Data analysis supports the importance of endoscopic hemostasis as the preferred treatment method in these cases. Endoscopic hemostasis not only provides effective stoppage of bleeding, but also allows for minimally invasive intervention, reducing the risk of complications and accelerating the patient’s recovery process.Thus, the present study highlights the importance of an individualized approach in the diagnosis and treatment of peptic ulcer disease in patients with liver cirrhosis. This confirms the need for a careful analysis of each clinical case, taking into account the characteristics of the pathology and the general condition of the patient, in order to achieve the most effective and safe treatment results.Although there were no statistically significant differences in localization, size and number of ulcers of the gastroduodenal zone, ulcer bleeding rates between groups with and without PHG or between different Child-Pugh cirrhosis classes, the study results highlight the importance of further study in this area.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- All authors have made significant contributions to the design, execution, analysis and writing of this study, and will share responsibility for the published material. Conflicts of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.Ethics approval: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of institute, Uzbekistan.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML