-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2024; 14(7): 1852-1855

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20241407.27

Received: Jun. 20, 2024; Accepted: Jul. 16, 2024; Published: Jul. 20, 2024

Catheter Ablation of Left-Sided Accessory Pathways by Transseptal Versus Transaortic Access

Rakhim Amirkulov, Khurshid Fozilov, Bakhtiyor Amirkulov, Berdimurat Sultanov, Shokhrukh Erkabayev

Department of Electrophysiological Study and Surgical Treatment of Complex Arrhythmias, Republican Specialized Scientific and Practical Medical Centre of Cardiology, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

Correspondence to: Rakhim Amirkulov, Department of Electrophysiological Study and Surgical Treatment of Complex Arrhythmias, Republican Specialized Scientific and Practical Medical Centre of Cardiology, Tashkent, Uzbekistan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

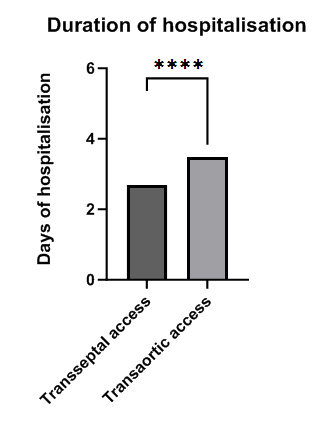

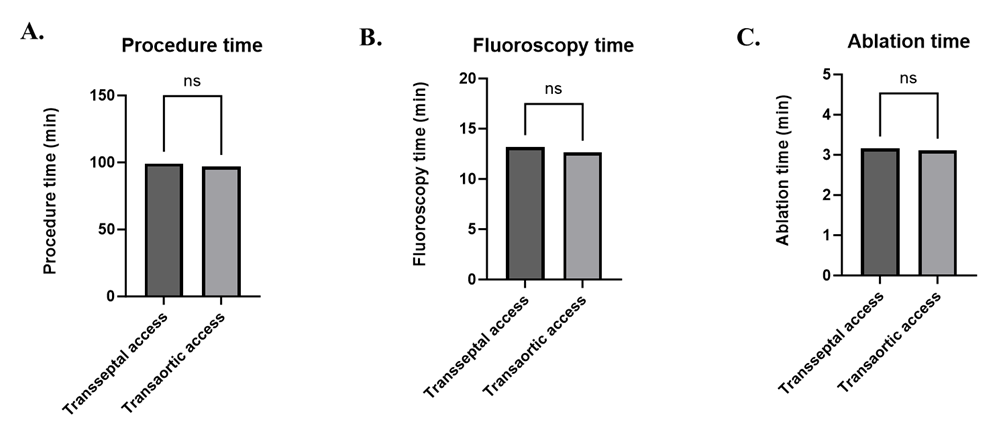

There are 2 approaches for ablation of left-sided APs in adults: transseptal (TS) and transaortic (TA). Our study aimed to compare distinct types of accesses (TS vs TA) in the ablation of left-sided APs. Ninety-three patients with left-sided APs were ablated by TS or TA, or both accesses between February 2016 and January 2019. Forty-two and 51 patients were ablated via TS (group I) and TA (group II) accesses, respectively. Acute success rate, duration of hospitalisation, procedure, fluoroscopy, and ablation time, and 5-year follow-up were evaluated. There was no significant difference in acute success rates of ablation between TS and TA accesses (p=1). Moreover, these approaches complement each other in cases when one particular access was ineffective. The duration of hospitalisation was significantly longer when using TA compared to TS access (p<0.0001). The procedure, fluoroscopy, and ablation time did not differ significantly between 2 approaches in this study. Five-year follow-up did not reveal significant difference in the recurrence rate between these accesses. There were no significant differences in terms of the studied indicators between 2 accesses. Both approaches should be used if one of them fails.

Keywords: Radiofrequency ablation, Accessory pathways, Transseptal access, Transaortic access, Electrophysiological study

Cite this paper: Rakhim Amirkulov, Khurshid Fozilov, Bakhtiyor Amirkulov, Berdimurat Sultanov, Shokhrukh Erkabayev, Catheter Ablation of Left-Sided Accessory Pathways by Transseptal Versus Transaortic Access, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 14 No. 7, 2024, pp. 1852-1855. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20241407.27.

1. Introduction

- Accessory pathways (APs) are the tracts connecting atria and ventricles parallelly to the atrioventricular (AV) node and can result in AV reentry tachycardia (AVRT) [1]. Because of the AP’s extremely high conduction qualities, cardiac pre-excitation may cause sudden cardiac death in less than 1% of people [2]. Pre-excitation affects 0.1% to 0.3% of the general population [3, 4]. About 60% of the pathways are located along the mitral valve and are called “left-free wall pathways”. Approximately 25% run along the septal side of the tricuspid or mitral valve and are classified as septal pathways. The remaining 15% are right-free wall pathways [5]. Catheter ablation is a primary choice for the treatment of APs, recent guidelines suggest ablation as a class I recommendation for symptomatic patients [3]. Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) is a procedure when AP is destroyed by utilising thermal energy from radiofrequency energy [6]. RFA is curative in approximately 95% of patients, however, it can fail sometimes due to different reasons, particularly, AP’s location. Utilising different types of catheters and accesses can improve the results of the ablation procedure. Right-sided APs can be ablated from the following accesses: subclavian or femoral veins, while there are 2 approaches for ablation of left-sided APs: transseptal (TS) and transaortic (TA). These approaches are distinct in terms of materials, technique, and complications. Usually, the approach can be chosen individually according to the operator’s preference. However, there is no clear proposed recommendation on the optimal access for catheter ablation of left-sided APs [7]. Our study aimed to compare distinct types of accesses (TS vs TA) in the ablation of left-sided APs.

2. Materials and Methods

- Ninety-three patients with both concealed and manifest left-sided single APs were ablated by TS or TA, or both accesses between February 2016 and January 2019. Fourty-two and 51 patients were ablated via TS (group I) and TA (group II) accesses, respectively. Both approaches were employed if catheter ablation failed with any particular access. Measurements such as the time of the procedure (measured from the moment of the first puncture until all sheaths are removed) and fluoroscopy, as well as the total duration of RF energy application were analysed. In a state of conscious sedation, all patients had electrophysiological (EP) study followed by ablation. When anesthesia was required, midazolam and propofol were administered. Written informed consent was signed by each patient. We compared the duration of the procedure, ablation and fluoroscopy, the success and complication rates associated with the procedure, as well as the recurrence rate at 5-year follow-up. All previously administered antiarrhythmic medications had been stopped for at least five half-lives before the procedure. Procedure detailsElectrophysiologic studyAll EP studies was performed utilizing the Labsystem Pro EP Recording System, (Bard electrophysiology, Boston Scientific). Patients with manifest APs were identified using a surface ECG, whereas the concealed form was revealed during the EP study. The following diagnostic catheters were used in all patients: the 6-F Webster decapolar diagnostic catheter (Biosense Webster) that was positioned inside the coronary sinus via the right internal jugular vein and the AVAIL Quadripolar Fixed Shape diagnostic Catheter (Biosense Webster) that was inserted apically into the right ventricle. To confirm the left-sided location of AP, the aforementioned diagnostic catheters, and also a 3.5 mm tip externally irrigated (Celsius ThermoCool electrophysiology catheter, Biosense Webster, CA) catheter, were used. This ablation catheter was inserted into the left heart by TS access through the femoral vein and/or retrogradely by TA access through the femoral artery. Wenckebach cycle lengths for the ventriculoatrial (VA) and atrioventricular (AV) conductions were measured, in addition to PR, QRS, QT, and basal cycle length. Since in most cases the cells of the APs have similar EP properties as cardiomyocytes, prolongation of the VA interval (decremental property of the AV node) during programmed stimulation of the right ventricle indicated the absence of a concealed AP. The shortest VA interval during AVRT and/or ventricular pacing was utilized in patients with manifest and concealed APs, while the shortest AV interval during sinus rhythm or atrial pacing was used to determine the ablation site in patients with only manifest AP. In the TS group, the right femoral vein was used to insert a TS 8.5-F sheath (SL1, St. Jude Medical, St. Paul, MN, USA) into the left atrium through either a TS puncture or a patent foramen ovale. Successful TS puncture was verified with the appearance of contrast material and bubbles in the left atrium during fluoroscopy and transesophageal echocardiography, respectively. After the dilator and needle were removed, the manually navigated catheter was positioned on the atrial side of the mitral annulus. In the TA group, the right femoral artery was used to insert the ablation catheter. Under the fluoroscopic control, the manually navigated catheter was passed through the aortic valve into the left ventricle, then the tip of the electrode was bent in the cranial direction so that it was directed to the ventricular side of the mitral annulus. As soon as left heart was achieved, heparinization was performed on each patient using 100–150 units/kg.Radiofrequency ablationThe 3.5 mm tip externally irrigated manually navigated catheter was used to perform ablation using an RF generator Stockert (Biosense Webster Inc.) at a maximum power of 40 W for 60-90 seconds. After the target site was located, the ablation catheter was used to deliver RF energy, unless the criteria for successful ablation were noted within 15 seconds, energy delivery discontinued. If the bidirectional conduction block through the AP was reached and maintained for 30 minutes the procedure was deemed effective. Statistical analysisProcedural success, ablation, fluoroscopy, and overall procedure times, complication and recurrence rates were all analysed for each case, stratified by type of access. GraphPad Prism 9 and Microsoft Excel 2013 were used for statistical analysis. The mean ± standard deviation (SD) was used to present continuous data. A percentage was used to display categorical data. The unpaired two-tailed Student's t-test was utilised to compare continuous data. When necessary, chi-square or Fisher's exact test analysis was used to ascertain the link between the categorical variables. P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.IRB approval This study was conducted in compliance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study’s protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB no. 11). Informed consent was obtained from all patients participating in the study.

3. Results and Discussion

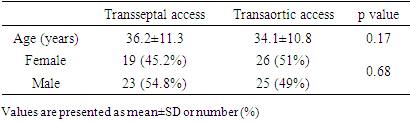

- Characteristics of the patients are presented in Table 1. All patients were elder than 18 years. The mean age was 36.2±11.3 years in group I and 34.1±10.8 in group II (p=0.17). There was no significant difference in sex distribution between the groups.

|

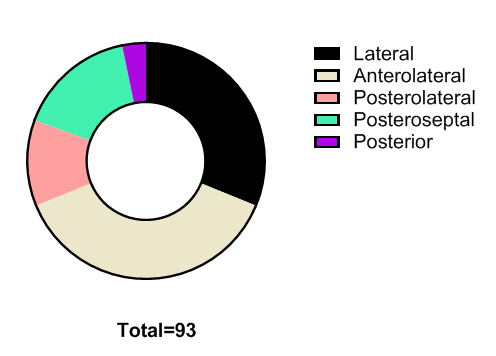

| Figure 1. Classification of accessory pathways depending on localization |

| Figure 2. Duration of hospitalisation of patients with ablation of accessory pathway via transseptal and transaortic accesses. ****p<0.0001 |

| Figure 3. Comparison of procedure (A), fluoroscopy (B), and ablation (C) times in ablation via transseptal or transaortic access |

4. Conclusions

- Both methods demonstrated similar performance in ablation of left-sided APs. It is preferable to use both accesses if one of them is ineffective.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML