-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2024; 14(7): 1784-1787

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20241407.12

Received: Jun. 17, 2024; Accepted: Jul. 8, 2024; Published: Jul. 10, 2024

Methods for Improving Surgical Outcomes of Posttraumatic Strictures in Children

Kh. A. Akilov, S. Shukurov, Sh. A. Nizomov

Center for Development of Professional Qualification of Medical Workers, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The aim of the study was to improve the treatment results of posttraumatic urethral strictures and urethral obliteration. Background. Posterior urethral injuries occur in 4-19% due to pelvic fractures as a result of motor vehicle trauma. Anterior urethral injuries occur during penile trauma. The difficulty of treatment is based on the following urinary complications: recurrent strictures, urinary incontinence and erectile dysfunction. Material and methods. The material was based on the treatment results of 70 children with post-traumatic urethral strictures aged from 5 to 13 years. All patients had previously been operated on in other medical institutions using Marion-Holtsov technique before they admitted to the pediatric surgical department. All patients were performed a modified Marion-Holtsov surgery with placement of a double-diameter catheter of our own modification. Results. The satisfactory results were observed in 69 (98.6%) children. Only 1 patient had recurrence of stricture and subsequently he was performed urethral repair from the scrotum skin. Discussion. Due to the use of a special drainage catheter, no local complications of infectious genesis were observed in any case and it allowed to prevent recurrence. Conclusion. The efficient drainage and washing of the anastomosis area with the use of a drainage catheter prevents its infection and has a beneficial effect on tissue healing processes.

Keywords: Urethra, Trauma, Stricture, Treatment

Cite this paper: Kh. A. Akilov, S. Shukurov, Sh. A. Nizomov, Methods for Improving Surgical Outcomes of Posttraumatic Strictures in Children, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 14 No. 7, 2024, pp. 1784-1787. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20241407.12.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Surgical treatment of posttraumatic strictures and urethral obliteration in pediatric practice has good results. Injuries of the prostate and bladder neck appear to be more frequent. Posterior urethral injuries occur in 4-19% due to pelvic fractures as a result of motor vehicle trauma. Anterior urethral injuries occur during penile trauma. The difficulty of treatment is based on the following urinary complications: recurrent strictures, urinary incontinence and erectile dysfunction [1,2]. A comparative analysis of the Clinical Guidelines for genitourinary trauma of the European Association of Urology (EAU) and the Société Internationale d'Urologie (SIU) showed that multicenter studies are still relevant today. It is necessary to optimize, improve the quality and increase the diagnostics and treatment of urethral injuries [3]. In spite of the progress achieved in surgical elimination of strictures and obliterations of traumatic origin of the membranous and prostatic urethra, the percentage of unsuccessful outcomes is still very high, and they range from 25 to 50% [4-10]. The reasons for unsuccessful outcomes are diverse, ranging from violations in primary care and diagnosis to imperfections and errors in surgical technique and postoperative management. In this regard, the issue of preventing the formation of posttraumatic strictures and their recurrence remains a particularly urgent problem of pediatric surgery. The aim of the study was to improve the treatment results of posttraumatic urethral strictures and urethral obliteration.

2. Material and Methods

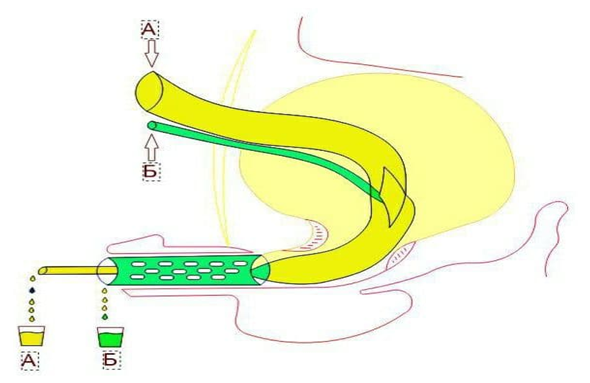

- Treatment results of 70 children aged from three to 15 years who were treated in the clinic of the Center for the Development of Professional Qualification of Medical Workers were analyzed. 27 (39%) of them had strictures and 43 (61%) had obliterations. By localization, we observed the following: in the membranous section - in 33 (47%) patients, in the prostatic section - in 17 (24%) or in both sections of the urethra - in 19 (27%). One patient (2%) had complete separation of the urethra from the bladder neck with subsequent development of a posterior urethral stricture. Pelvic bone injuries were the cause in 51 children (73%) and falls from height - in 19 (27%). The ages of the children varied as follows: 5 children were from 3 to 7 years, 38 - were from 7 to 12 years, and 37 ones were from 12 to 15 years old. Previously, 51 (73%) children had been operated on in the clinics of their place of residence. Thus, their strictures and obliterations were recurrent when they addressed our center. Twenty-seven of them were operated according to the Marion-Holtsov technique, and 24 patients were operated according to the Kroyss-Fronstein technique. After these surgeries 17 patients were performed a prolonged unsuccessful urethral bouginage. The remaining 19 (27%) patients had only an epicystostomy applied before hospitalization to our clinic.All patients were performed ascending and descending urethrography, ultrasound of the urethra and bladder, and urethroscopy. Fifty-five patients were performed voiding cystourethrography. Nineteen patients were examined for bladder neck, internal urethral orifice through cystostomy fistula. After surgery, when catheters and drains were removed, control uroflowmetry was performed. All 70 patients already had suprapubic cystostomy drainage upon admission. After collecting urine for bacteriological examination, drainage was replaced and the urinary tract was sanitized. In case of "controllability" of urinary tract infection we performed surgical treatment - a modified Marion- Holtsov surgery with the installation of a special catheter (patent IDP № 05277, 19.11.2001). We used a perineal incision strictly along the midline, giving wide access to the posterior urethra. In contrast to the previous incision, the muscles are not damaged when deepening this incision. After dissecting the skin, subcutaneous tissue and exposing the surface of the bulbospongiosus muscle, it was separated from the spongy tissue of the urethral bulb. Then we retracted the muscle on both sides, preserving it as much as possible from damage, because damage to this muscle is fraught with the subsequent development of erectile dysfunction.We separated the spongiosa together with the urethra from the fixation site by dissecting the ligament attaching the lower edge of the pubic bones. At the same time, we do not separate the spongiosal tissue from the urethra, because the wall of the pediatric urethra is very thin and delicate. We continued the release of the bulbous part of the urethra in depth along with the membranous part to the prostate gland. After that, we cut off the urethra from the scarred part (in case of strictures and obliterations of the membranous section) or as close as possible to the scarred part of the urethra (when there is a stricture or obliteration in the prostatic section, or in cases of separation of the urethra from the bladder neck). It must be remembered that every millimeter of non-scarred tissue of the urethral wall is very valuable for protecting the anastomotic line from tension. In cases of repeated surgery, due to numerous adhesions and scars of surrounding tissues, as well as due to complete obliteration of the membranous, prostatic or both of these parts of the urethra, it is not possible to punctually follow the principle of topographic-anatomical surgeries. For this reason, at this stage of the surgery, the main focus should be on carefully releasing of the urethra distal part and cutting it off from the obliterated or stricturally changed part of the urethra. Proximal scar removal should be started from the inner surface of the symphysis pubis in order to avoid injury of the prostate as much as possible. After cutting off the scar tissue and finding the blunt end of the proximal part of the urethra, its wall was carefully dissected and their ends were freed from the surrounding tissue.After careful preparation of both ends of the urethra for end-to-end anastomosis, the bladder was drained with a two-diameter vesicourethral tube. The proximal end (diameter 0.5-0.6 cm) was brought out to the suprapubic area, at the level of Lieto triangle. From the initial part of the bladder neck, the wall of this tube becomes thinner (diameter 0.15- 0.18 cm) and another catheter with an outer diameter of 0.4-0.5 cm, with small multiple drainage holes on its wall, was placed on it. The end of both catheters was brought out through the external orifice of the urethra at 5-6 cm (Fig. 1).

3. Results

- Postoperative treatment did not differ from generally accepted guidelines. But at the same time, we especially focused on the following factors: selection of a parenteral antibiotic, when the basis was not only the result of a bacteriological study, but also the features of the microbial landscape of the entire cohort of patients. Nosocomial flora was predominant in our patients, when a protected antibiotic with bactericidal ability against nosocomial strains with sufficient evidence base should be chosen. We used constant irrigation of the bladder with sterile solutions with antiseptic component. Chlorhexidine bigluconate or dioxidine was used for this procedure.We also used regular irrigation of the urethral anastomosis site followed by antibiotic administration through our proposed microcatheter. In this way we performed systematic local wound sanitation and local treatment of infection.Microbiological examination of urine to determine the pathogen and sensitivity to antibacterial drugs was performed in 66 (100%) patients. In urine examination, no microflora growth was found in 15 (22.7%) children, positive result of urine culture was in 51 (77.3%) patients. In 31 (47.1) of them, growth of microorganisms of the Enterobacteriaceae family was detected, in 15 (22.7%) patients growth of microbes of the Proteus family, in 3 (4.5%) - St. saprophiticus and in 2 (3.0%) - Candida was detected. We explain this variant of uropathogen seeding by the fact that 15 (22.8%) children received antibacterial treatment prior to hospitalization.Sensitivity analysis of isolated microorganisms was performed only with regard to antibacterial drugs approved for the use in pediatric practice. Irrigation of the anastomotic area was carried out with sterile saline (0.9% sodium chloride solution) with an antiseptic. Chlorhexidine bigluconate (in all age groups) or Dioxidine (in the older age group only) were used as the antiseptic component. For antiseptic treatment of the urethral wound site (anastomosis) 0.5% sterile solution was prepared by diluting the drug 1:40 in 0.9% physiological solution (sodium chloride) with sterile glycerin. A special feature of this solution is its ability to increase the sensitivity of bacteria to chloramphenicol, kanamycin, neomycin, and cephalosporins. For irrigations, 5-10 ml of the solution was injected through the drain into the anastomosis area, usually 2-3 times a day. The treatment course was 7-9 days, daily, until the catheter was removed.

4. Discussion

- Due to the use of a special drainage catheter, no local complications of infectious genesis were observed in any case, which allowed to prevent recurrence. Only in one case we observed recurrence of stricture. A greater extent of diastasis between the healthy ends of the urethra was found at reoperation. It was larger than 6cm, for technical reasons we had to use a scrotal skin flap on a vascular pedicle to repair the urethra in this patient. Local manipulations and surgical technique determined a smooth course of the postoperative period: wounds healed initially, which allowed to remove a special drainage catheter from the urethra not later than 8-9 days. After surgery, the maximum bladder volume, bladder wall thickness, residual urine volume and urination time were monitored. The results of these studies did not reveal any deviations from the age-related norm criteria. Also, no significant differences with the data from long-term examinations were observed. In 69 children there were no complaints, urine flow was normal, the data of simplified uroflowmetric index (Goldberg B.B., 1974) were within normal limits (14.3+3.3 ml/s after catheter removal on the 10th day after surgery; 23.6+4.9 ml/s 3-6 months after surgery; 24.9+5.8 ml/s 12 months after surgery, p > 0.05). Considering all objective data, no recurrence of the stricture was noted.

5. Conclusions

- Careful preparation and correct execution of the stages of surgical manipulation of urethral anastomosis with the use of a special drainage catheter, with correct selection of antimicrobial agents for parenteral and local application allowed to achieve good results in 98.6% of cases, including cases of repeated correction in cases of recurrent strictures and urethral obliterations. The proposed special drainage catheter suggests encouraging results for widespread use.

Conflict of Interests’ Statement

- The authors declare no conflict of interest. This study does not include the involvement of any budgetary, grant or other funds. The article is published for the first time and is part of a scientific work.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors express their gratitude to the management of the multidisciplinary clinic of Center for Development of Professional Qualification of Medical Workers for the material provided to our study.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML