D. A. Ochilova

Bukhara State Medical Institute, Bukhara, Uzbekistan

Correspondence to: D. A. Ochilova, Bukhara State Medical Institute, Bukhara, Uzbekistan.

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Abstract

The paper studied anthropometric indicators of adolescents with Down syndrome and conducted a comparative analysis with indicators of healthy adolescents. Based on the results obtained, weak anthropometric indicators have been identified in adolescents with Down syndrome.

Keywords:

Down syndrome, Anthropometry, Adolescents, Physical development

Cite this paper: D. A. Ochilova, Comparative Analysis of Anthropometric Indicators of Physical Development of Adolescents and Healthy Adolescents with Down Syndrome, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 14 No. 6, 2024, pp. 1546-1549. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20241406.16.

1. Introduction

High interest in trisomy-Down syndrome (DS) on the 21st pair of chromosomes is explained by its frequent occurrence, limited clinical signs, as well as better survival compared to other chromosomal syndromes, and for this reason – the possibility of early diagnostics. DS is considered a treatable or postnatal irreparable, socially significant disease that manifests itself in a huge problem for the family and society as a whole. Up to 40% of the beds fund in the children's home and disabled home is occupied by DS-available patients.A number of scientific studies conducted to study the frequency of occurrence of DS (Chebotarev A.N., Lunga I.N. et al.), peculiarities of Mosaic variants (Belyakova T.K., Gavrilova V.I. et al.), immune status (Schwarz E.I., Ostrovsky A.D. et al.), reproductive function (Kristesashvili D.I. et al.), blood system (Agarwal B.R., Chijova Z.P., Jurgu-tis R.P., Popnikolov B.C. et al.), metabolism (Davidenkova E.F., Shtil-Bane I.I., Berlinskaya D.K. et al.) and others, and many new scientific data were obtained. Alternatively, the detected changes are not being adequately considered in terms of the possibility of their use in clinical practice.Objective: to study anthropometric parameters and identify age-specific weak anthropometric indicators in adolescents with Down syndrome.Tasks: to determine the indicators of the physical development of adolescents with Down syndrome and compare with the indicators of healthy adolescents.Conducting comparative morphometry of body parts in adolescents with Down syndrome and healthy adolescents of the same age, identifying weak anthropometric indicators, taking into account the age of adolescents with Down syndrome.

2. Materials and Methods

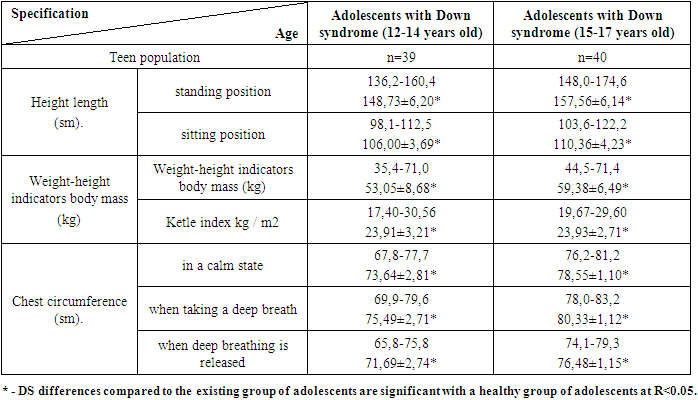

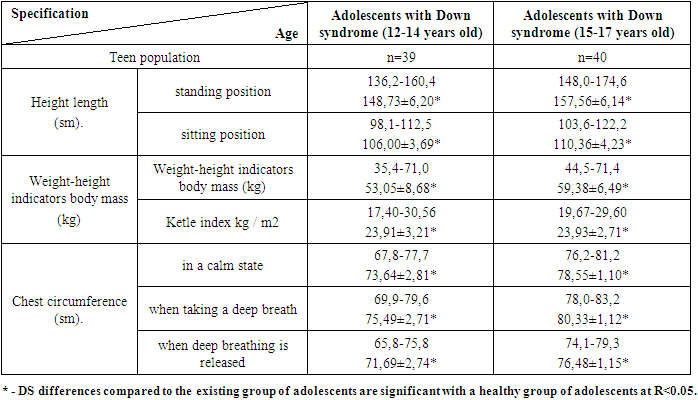

During the studies, 79 adolescents aged 12 to 17 years with Down syndrome living in Bukhara, Navoi and Kashkadarya regions were involved in the examinations. Also, for the control group, 100 of the School No. 17 in Bukhara were selected by random selection from 1,248 healthy adolescents aged 12-17 (Owen 1966). The studies revealed the upper and lower mucosa, chest, height, weight, and Ketle index of the adolescents involved.The Ketle index was determined using the formula TVI=weight/height2 and expressed in kg/m2 after adolescents ' body weight and standing height lengths were measured. The results obtained were evaluated under the WHO (1997) classification: weight deficit at TVI < 18.5; normative body weight at TVI – 18.6-24.9; excess body weight at TVI – 25.0-29.9; obesity Grade I at TVI 30-34.9; obesity at TVI – 35.0 – 39.9; obesity Grade II at TVI > 40.The results of the study and their analysis: as the main anthropometric indicators of physical development, indicators such as height, body weight, Ketle index and chest circumference were studied in adolescents with Down syndrome in the study group.We can observe that in adolescents with Down syndrome, the height indicators increase in age-appropriate both in a sitting and standing position, but it was found in our studies that the growth trend is significantly lower than in healthy adolescents.Analysis of body weight and Ketle index indicators in adolescents with Down syndrome in research groups showed that, along with increasing body weight in accordance with age, the Ketle index recorded almost the same results in both the 12-14-year-old group and the 15-17-year-old group (23.91 and 23.93, respectively).DS in existing adolescents we can observe that the index of chest circumference increases in a calm state, when breathing and exhaling, in accordance with age in different age groups.Table 1. DS anthropometric indicators of the physical development of existing adolescents

|

| |

|

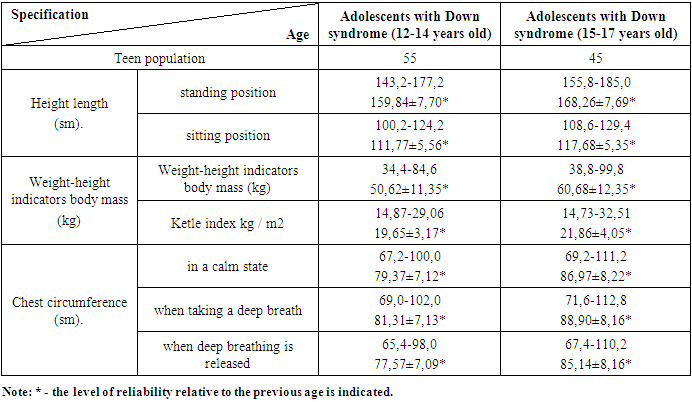

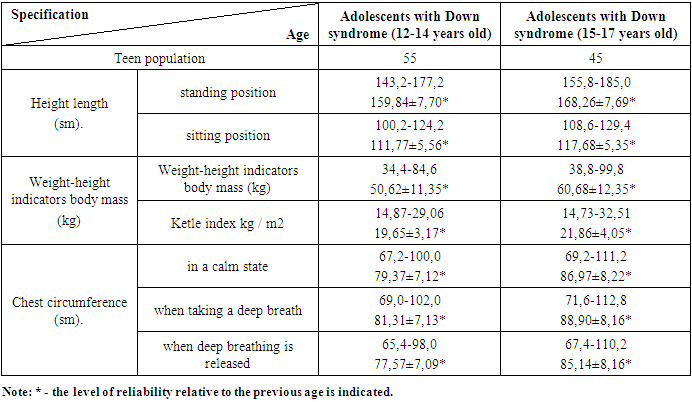

In healthy adolescents, height indicators were observed to increase with age in a sitting and standing position. It has been found that this growth trend is significantly higher in healthy adolescents than in adolescents in the main research group. In the analysis of body weight and Ketle index indicators, an increase in body weight and Ketle index was observed in healthy adolescents in the control group in accordance with age, however, it should be noted that among adolescents aged 12-14 years, body weight showed a higher result in healthy adolescents, while in adolescents with Down syndrome in the 15-17 year old group, high In contrast, the ketle index was noted to be statistically higher in adolescents in the primary study group with Down syndrome, both in the 12-to 14-year-old group and in the 15-to 17-year-old group.In healthy adolescents, it was noted that the index of chest circumference when inhaled and exhaled in a calm state increased with age in different age groups. Especially in the group of healthy adolescents aged 15-17 years, it seemed that the trend of growing these indicators was higher.Table 2. Anthropometric indicators of the physical development of healthy adolescents

|

| |

|

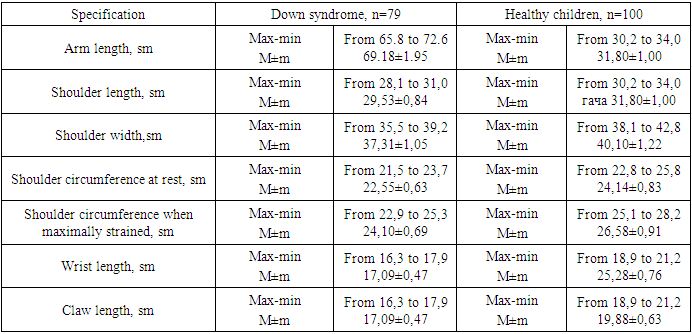

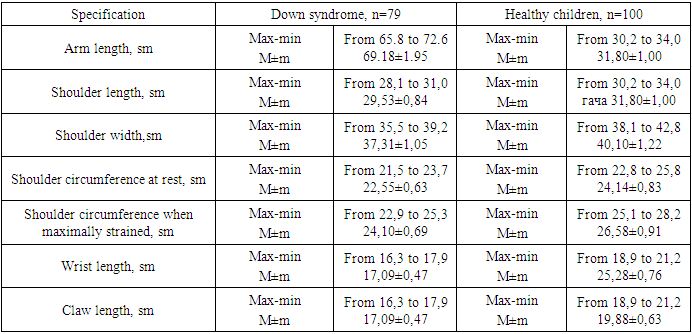

In our research work, we studied the peculiarities of anthropometric indicators in patient adolescents who are healthy and have DS. According to our data, DS in existing patient adolescents, the indicators of physical development lag behind those of healthy adolescents.It can be said that DS was found in our studies that the height of existing adolescents is slightly lower in all age groups compared to healthy adolescents (148.7 and 159.8, respectively). According to body weight and Ketle index indicators, in contrast DS recorded statistically significantly higher results in existing adolescent groups than healthy adolescents (23.9 and 21.8, respectively). Chest circumference based on the results of the examination according to different periods of adolescents there are DS in adolescents aged 12-14 years, the chest circumference in different cases (when breathing calmly, deeply, and so on).) lower scores compared to healthy adolescents (73.6 and 79.3 respectively) can be observed, whereas in adolescence, 15-17 years of age, we can observe a statistically plausible increase in this difference (78.5 and 86.7 respectively). All the results obtained indicate a radical change in the physical formation of the body in DS, which is clearly manifested in the 15-17 year old period of adolescence.DS was found to be 1.17 times lower in height (17.0%) in existing adolescents due to poor development of muscle tissue and low asthenic body structure. There is a great influence of children and adolescents on the level of physical development, lifestyle, environment and educational system.DS-present adolescents showed an increase in body weight and height proportionality-i.e. the Ketle index-by 1.19 times (19%) compared to otherwise healthy adolescents. This proves that DS has an imbalance in physical development rates in existing adolescents. In adolescents with DS mvjud, an increase in the Ketle index is reduced by a decrease in basal metabolic rate, low levels of physical activity and poor diet. Correcting these changes early on reduces the risk of developing future medical consequences associated with DS.The circumference of the chest was found to be an average of 73.64±2.81 sm (7.78% less than healthy adolescents) in adolescents with DS aged 12-14, as well as an average of 78.55±1.10 CM (10.71% less than healthy adolescents) in adolescents with DS aged 15-17 years.In healthy adolescents aged 12-14 years, the circumference of the chest was found to be on average 79.37±7.12 sm, while in healthy adolescents aged 15-17 years, the average was 86.97±8.22 during studies. DS has been observed to have an increased lag in the chest circumference indicator compared to healthy adolescents with an increase in age in existing adolescents.Studies have shown that the arm length of DS existing adolescents was 69.18±1.95 sm (65.8 sm to 72.6 sm), shoulder length was 29.53±0.84 sm (28.1 sm to 31 sm), shoulder width was 37.31±1.05 sm (35.5 sm to 39.2 sm). The shoulder circumference is 22.55±0.63 sm (21.5 cm to 23.7 sm) in a calm situation, and 24.88±0.70 sm (23.7 sm to 26.1 sm) in maximum tension, wrist length 24.10±0.69 sm (22.9 sm to 25.3 sm), claw length 17.09±0.47 sm (16.3 sm to 17.9 sm) was found to constitute.Healthy adolescents are known to have an arm length of 74.19±2.37 sm (70.1 sm to 79.3 sm), An shoulder length of 31.80±1.00 sm (30.2 sm to 34.0 sm), and an shoulder width of 40.10±1.22 sm (38.1 sm to 42.8 sm). In a calm situation, the shoulder circumference is 24.14±0.83 sm (22.8 sm to 25.8 sm), while in maximum tension it is 26.58±0.91 sm (25.1 sm to 28.2 sm), wrist length is 25.28±0.76 sm (24.3 sm to 26.8 sm), and claw length is 19.88±0.63 sm (18.9 smto 21.2 sm) the equivalent of has found evidence in research.Table 3. Anthropometric indicators of high rates of patients and healthy adolescents present in DS

|

| |

|

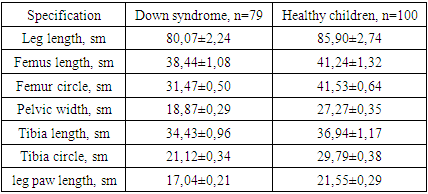

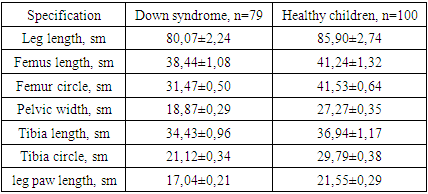

In healthy adolescents, DS was found to grow 1.19 times the total length of the arm (19.0%) to 1.15 times the length of the shoulder (15.0%), 1.21 times the width of the shoulder (21.0%), 1.24 times the circumference of the shoulder (24.0%) to 1.17 times the length of the wrist (17.0%), and 1.22 times the length of the claw (22.0%).DS existing adolescents have legs ranging in length from 76.2 sm to 84.0 sm, averaging 80.07±2.24 sm, thigh length from 36.6 sm to 40.3 sm, averaging 38.44±1.08 sm, thigh circumference from 30.8 sm to 32.1 sm, averaging 31.47±0.50 sm. The tube varies in width from 18.2 sm to 19.5 sm, averaging 18.87±0.29 sm, the calf length from 32.8 sm to 36.1 sm, averaging 34.43±0.96 sm, while the calf circumference increases from 20.6 sm to 21.7 sm, averaging 21.12±0.34 sm, the ankle length varies from 16.6 sm to 17.5 sm, averaging 17.04±0.21 sm it has been found to constitute ni.Healthy adolescents have a leg length of 81.4 sm to 91.8 sm, with an average of 85.90±2.74 sm, a thigh length of 39.1 sm to 44.1 sm, an average of 41.24±1.32 sm, a thigh circumference of 40.6 sm to 43.0 sm, and an average of 41.53±0.64 sm. The tube varies in width from 26.8 CM to 27.9 cm, growing to an average of 27.27±0.35 sm with a calf length of 35.0 sm to 39.5 sm with an average of 36.94±1.17 sm, and a calf circumference of 29.2 sm to 30.3 sm, growing to an average of 29.79±0.38 sm, with a toe length of 21.0 sm to 22.0 sm, with an average of 21.5±0.29 sm equality was observed.Table 4. Anthropometric indicators of the lower mucosa of existing and healthy adolescents 15-year-old DS

|

| |

|

3. Conclusions

DS found that existing patient adolescents had lower height compared to healthy adolescents. DS-present adolescents showed an increase in body weight and height proportionality-i.e. the Ketle index-by 1.19 times (19%) compared to otherwise healthy adolescents. This proves that DS has an imbalance in physical development rates in existing adolescents.Down syndrome has patient adolescents the length of the upper and lower mucosa is short compared to the length of the upper mucosa of healthy adolescents, and Lagging was mainly due to a decrease in the length of the shoulder, the growth of the hip and calf circles.

References

| [1] | Akhmedova R.M. Assessment of the quality of life of adolescents suffering from endocrine diseases // Pediatrician. - 2016. - Vol. 7., No. 1. - pp. 16-21. |

| [2] | Gnetetskaya V.A., G.G. Guzeev, I.V. Kanivets, S.A. Korostelev, H.A. Semenova. Chromosomal micromatrix analysis in the practice of modern genetic counseling. // Children's Hospital. -2013, No. 4 (54), pp. 56-62. |

| [3] | Denisova E.G. Assessment of dental status in children with Down syndrome. Abstract. PhD, 2022 Moscow. 32 pages. |

| [4] | Semenova N.A. The state of health of children with Down syndrome. Abstract. PhD 2014. Moscow. 43 pages. |

| [5] | Chubarova A.I., H.A. Semenova. What do the numbers say? Physical development of children of the first year of life with Down syndrome. // Down syndrome. XXI century. -2022. -№2 (9), pp. 12-21. |

| [6] | Modeling of Down syndrome // Down syndrome XXI century. – 2009; 2: 6. |

| [7] | Bull M.J. Down Syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2020 Jun 11; 382(24): 2344-2352. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1706537. PMID: 32521135. |

| [8] | Hatch-Stein J.A., Zemel B.S., Prasad D., et al. Body composition and BMI growth charts in children with Down syndrome. Pediatrics 2016; 138(4): e20160541 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Growth charts for children with Down syndrome (https://www.cdc .gov/ncbddd/birthdefects/downsyndrome/ growth-charts.html). |

| [9] | Tsou A.Y., Bulova P., Capone G., Chicoine B., Gelaro B., Harville T.O., Martin B.A., McGuire D.E., McKelvey K.D., Peterson M., Tyler C., Wells M., Whitten M.S. Global Down Syndrome Foundation Medical Care Guidelines for Adults with Down Syndrome Workgroup. Medical Care of Adults With Down Syndrome: A Clinical Guideline. JAMA. 2020 Oct 20; 324(15): 1543-1556. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.17024. PMID: 33079159. |

| [10] | Antonarakis S.E., Skotko B.G., Rafii M.S. et al. Down syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primer. 2020; 6:9. DOI: 10.1038/s41572-019-0143-7. |

| [11] | Demikova N.S., Podolnaya M.A., Lapina A.S. et al. Dynamics of the frequency of trisomia 21 (Down syndrome) in the regions of the Russian Federation in 2011–2017. Pediatrics. 2019; 98(2): 43–48 (in Russ.)]. DOI: 10.24110/0031-403X-2019-98-2-42-48. |

| [12] | Cuckle H. Rethinking second-trimester Down-syndrome screening in the cell-free DNA era. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2019; 54:431–436. DOI: 10.1002/uog.20360. |

| [13] | Yaqoob M., Manzoor J., Hyder S.N. et al. Congenital heart disease and thyroid dysfunction in Down syndrome reported at Children`s Hospital, Lahore, Pakistan. Turk J Pediatr. 2019; 61: 915–924. DOI: 10.24953/turkjped.2019.06.013. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML