Kuchimova Charos Azamatovna, Khaydarova Dilorom Safoevna, Abdurazakova Robiya Sheralievna, Ibragimova Muazzam Kholdorovna, Kubaev Rustam Murodullaevich

Samarkand State Medical University, Uzbekistan

Correspondence to: Kuchimova Charos Azamatovna, Samarkand State Medical University, Uzbekistan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Abstract

As the prevalence of affective disorders increases, long-term somatized depressive disorders are receiving increasing attention. According to statistics of the World Health Organization (WHO), by 2030, somatized depression will become the main cause of disability of the world population. According to epidemiological studies, the prevalence of the phenomenon of somatization among the population is 25-30% (Schepank N. et al., 2020), AJ Macdonald et al. (2019), according to R. Kellner (2016), somatized symptoms are observed in physically healthy individuals in 10-80% of cases, in which panic and restlessness are observed. N. Ursin (2017) noted that 40% of patients with “persistent pain compensation” (temporary incapacity) and 40% permanent incapacity were observed in patients whose complaints did not correspond to objective findings. Tendency to somatization is one of the most characteristic symptoms of the modern pathomorphosis of depression, regardless of the nature, depth, and expressiveness of the depressive affect.

Keywords:

Somatized depression, Hypothymia modality, Panic disorders

Cite this paper: Kuchimova Charos Azamatovna, Khaydarova Dilorom Safoevna, Abdurazakova Robiya Sheralievna, Ibragimova Muazzam Kholdorovna, Kubaev Rustam Murodullaevich, Clinical Characteristics and Prognostic Criteria of Somatized Depression in General Somatic Practice, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 14 No. 4, 2024, pp. 1103-1108. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20241404.63.

1. The Purpose of the Study

It consists in determining clinical-psychopathological characteristics and prognostic criteria of somatized depressions in general somatic practice.

2. Research Tasks

1. To determine the clinical-psychopathological characteristics of somatized depression, the laws of its formation;2. To determine the degree of expression of affective symptoms, symptoms of generalized anxiety disorders in the hypothymia modality;3. Assessment of risk factors affecting the chronic course of somatized depression, predictors of the risk of development;4. Based on statistical-catamnestic analyses, to determine the average number of treatment of patients in a mental hospital in five-year periods and the duration of the periods between them;

3. Research Materials and Methods

The research was conducted in the dispensary department and day-patient hospital of the psychiatric hospital of Samarkand region during 2019-2022. A total of 134 patients with affective disorders were examined, in whom mild and moderate levels of somatized depressive disorders were determined by clinical and clinical-psychopathological methods. The criteria for inclusion in the general group consisted of the following:Bipolar affective disorder, mild or moderate depression with somatic symptoms (F31.31); bipolar affective disorder, mild or moderate depression without somatic symptoms (F31.30); the presence of a prolonged subdepressive state in these cases; The duration of the subdepressive state in the patients at the time of the study should not be less than 2 years; Expression of subdepressive symptomatology according to the Hamilton scale is less than 10 points and not more than 26 points (HDRS-21). The age of patients should be older than 18 years; Voluntary consent of patients to participate in research; Availability of outpatient follow-up of patients until the end of the study. Included in the exclusion criteria: Age of patients is less than 18 years; acute hallucinatory - obsessive states of various etiologies; Having acute somatic and neurological diseases; Discontent or inability of the patient to participate in the research; Pregnancy, lactation.

4. Research Methods

Clinical-psychopathological, clinical-typological, clinical-catamnestic, psychometric, experimental-psychological, clinical-genealogical, statistical methods were used in scientific research.

5. Research Results

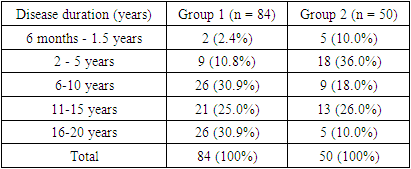

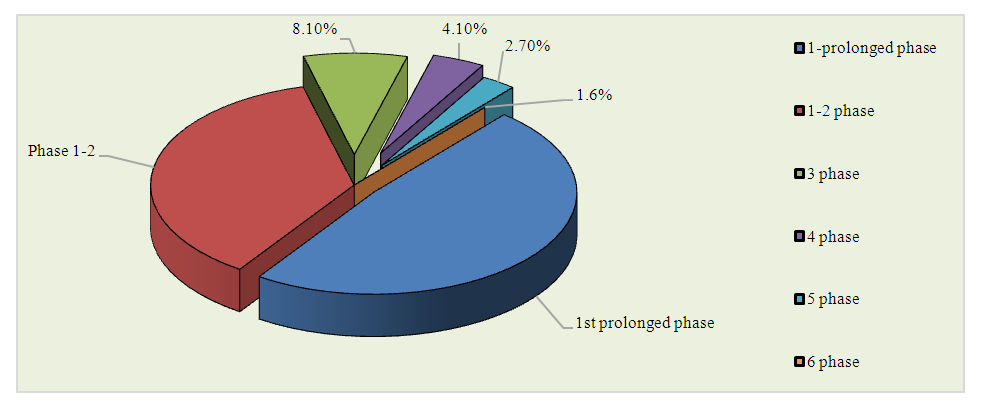

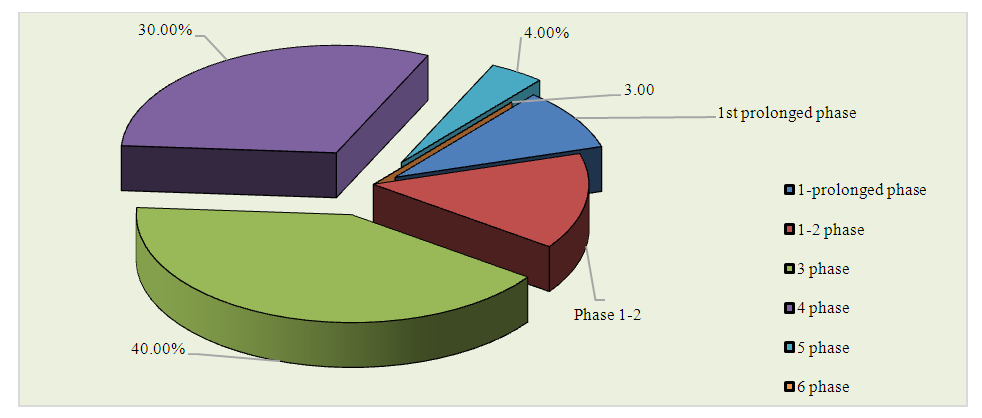

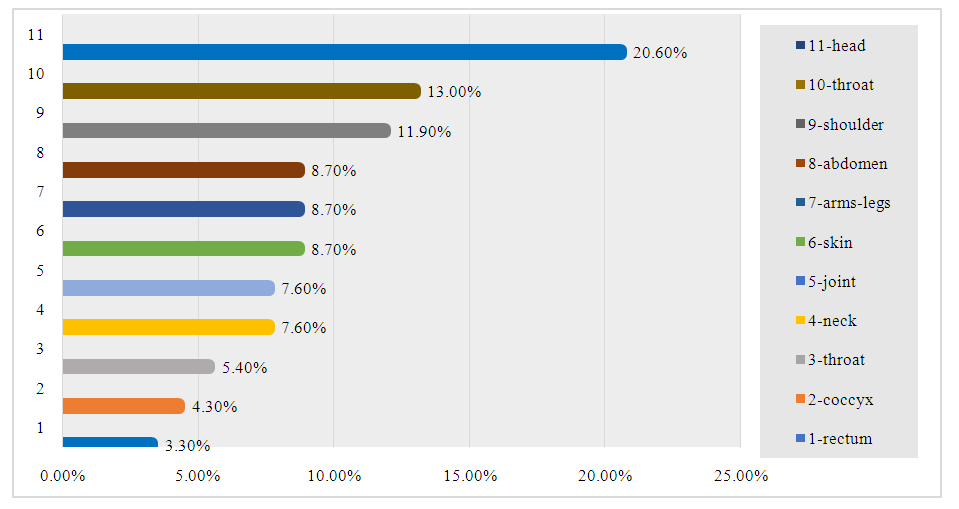

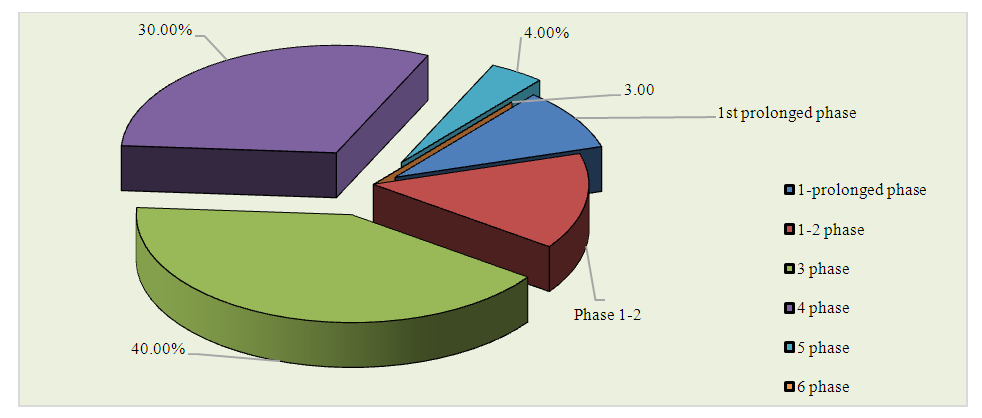

The results of the study were based on the data of the comparative analysis of the main and control groups. When the relationship between the duration of the disease and the number of subdepressive phases in the first group of patients was studied, in 47.6% of cases the disease was prolonged before the onset, that is, the first prolonged subdepressive phase was also considered the debut of the illness. 1 or 2 subdepressive phases were observed before the first protracted phase in 35.9% of cases. (Figure 1). | Figure 1. Number of depressive phases before the first protracted phase in group 1 patients |

In the second group of patients, when the relationship between the duration of the disease and the number of subdepressive phases before the first protracted phase was studied, in 9.0% of cases the disease was protracted before the onset, that is, the first protracted subdepressive phase was also considered the debut of the disease. 1 or 2 subdepressive phases were observed before the first protracted phase in 14.0% of cases.  | Figure 2. Number of depressive phases before the first protracted phase in group 2 patients |

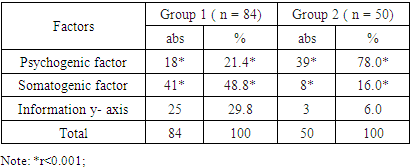

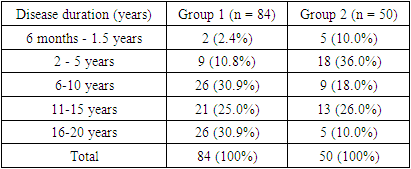

In group 1 patients, the duration of the disease from 6 to 20 years was determined and was 86.8%, and in group 2, the duration of the disease from 2 to 15 years was 80.0% (the average duration of the disease in group 1 patients was 15.4±1.6 years, and in group 2 it was 9.02±2.4 years), (Table 1).Table 1. The duration of the disease in groups

|

| |

|

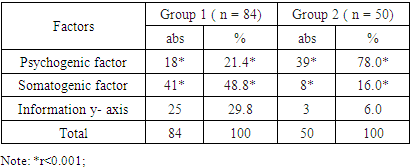

In the distribution of previously observed subdepressive attacks in the groups by duration, 6 months to 2 years (57.1%) were observed in group 1, observations are more reliable in group 2, previous subdepressive attacks were observed from 1.5 months to 3 months (50%). In 42.9% of group 1 and 100% in group 2, attacks were observed from 1.5 to 6 months, that is, they are not considered long-lasting, but 57.1% of group 1 lasted longer than the previous one. In 53.6% of patients of group 1 and in 34.0% of patients of group 2, subdepressive state started acutely. Expressed panic was combined with depressed mood, sleep was disturbed for 3 weeks-1.5 months, appetite was lost, tachycardia attacks appeared, labor activity decreased. After a while, a sense of hopelessness arose and interest waned. Patients immediately referred to a psychiatrist. 46.4% of the remaining patients of group 1 and 66.0% of patients of group 2 had a gradual onset of psychopathological symptoms. For 2.5-4 months, there was a decrease in appetite, irritability, extreme fatigue, crying, headaches, sleep disorders (feeling of lack of rest), and then total night insomnia appeared. A feeling of tension, restlessness was observed episodically. Patients have decreased attention and memory, and their self-confidence has decreased. Low mood, tearfulness, rapid irritability were observed with panic. In addition, sweating, tachycardia attacks, chest pains, constipation, decreased body mass, decreased libido were observed.Remission duration is shorter in prolonged somatized depressive patients. Patients of group 2 experienced complete recovery from subdepressive state, patients of group 1 experienced slight affective changes and residual symptoms. Among the patients of the first group, the somatogenic factor prevailed in most cases compared to the patients of the second group, i.e., 48.8% versus 16.0% (r<0.001). Patients of the second group were more psychogenic compared to patients of the first group, 21.4% vs. 78.0% (r<0.005), (table 2).Table 2. Description of factors affecting patients

|

| |

|

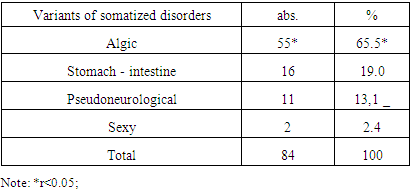

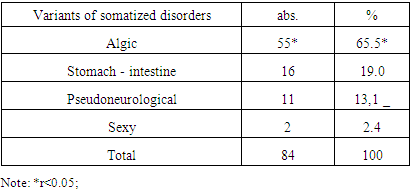

In patients, the main focus was on premorbid exogenous factors of the brain (BMEO). Exogenous factors included perinatal pathology (complicated pregnancy, premature birth, prolonged labor, asphyxia at birth), infections and convulsive conditions at a young age with obvious intoxication, neuroinfections, mild and moderate brain injuries. The performed pathology was observed in group 1 patients: perinatal pathology in 10.7%, childhood infections in 48.8%, brain injuries in 40.5%, in which in 70.1% of cases the performed brain injury was observed with loss of consciousness. Childhood infections had a large number of patients in the first group (48.8%).During the examination, the most frequently observed symptoms were distinguished: hypothymia, loss of interest, extreme fatigue, impressionability, psychomotor inhibition, psychomotor restlessness, suicidal thoughts, disturbed sleep, decreased appetite, diurnal changes, hypochondriac and non-hypochondriac visceral panic. Depressed mood was observed in both groups of patients (85.7% and 88.0%). Vitalization of subdepressive affect in group 2 patients in the form of "suddenly falling" mood ("heaviness in the heart", "sinking, scratching in the chest", "bitter, exhausting heartache", "heartache hurts", "stone in the heart", "presses the chest" ") is observed. In hypothymia, a sad state is reflected ("gloomy mood, everything is against a gray background"). Patients of the 1st group have a sense of panic ("unsettled mind", "as if something bad is happening"). More than half of the patients of group 2 (66.0%) and most of patients of group 1 (94.0%) have visceral panic attacks, hypochondriac content with intracorporeal danger fables, which can be evaluated as symptoms of generalized panic disorders. Hypochondriacal panic attacks had reliable indicators mainly in group 1 patients (r<0.001).Most of the patients of the first and second groups (86.9% and 88.0%) had a loss of interest, and they were often accompanied by a loss of satisfaction (“nothing could please me”, there is no desire to do something, it is done out of compulsion), “no one doesn't care"). Extreme fatigue was observed in all patients, in most cases (94.0%) it was observed in patients of the second group (doing everything with strength", does everything with the eyes, but there is no strength"). Most of the patients of both groups (73.8% and 74.0%) have high sensitivity (affected by everything) along with depressed mood. From the words of the patients, it is observed that they cry over trivial things, bad or good words (86.9% and 60.0%). Psychomotor retardation has an objective description: "the patient is inhibited from the side of movement, speaks little, performs simple movements with difficulty" or "speech slows down, answers with pauses". The symptoms of ideational inhibition are expressed by the patient's complaints of the type "my head seems to be full of something, I think with difficulty." Psychomotor inhibition was equally expressed in both groups of patients. Psychomotor agitation is observed in the form of inability to sit ("I can't find a place to sit") and is often observed in patients of the first group (56.0% and 8.0%, r<0.001).Sleep disorders are observed in both groups of patients, but occur in the undifferentiated type of insomnia. Decreased appetite had almost the same indicators in both groups of patients (82.1% and 82.0%). Diurnal changes were observed among patients: "can't move in the morning, walks a little in the afternoon" was 51.1% of patients of the first group and 72.0% of patients of the second group (p<0.05).Somatized symptomatology includes: painful sensations in at least 4 parts of the body; pain syndrome and pronounced functional disorders of the gastrointestinal tract (nausea, vomiting, inability to tolerate certain products); pain syndrome and functional disorders in the sexual sphere; pseudoneurological symptoms (paraparesis, incoordination, diplopia, something stuck in the throat, aphonia, difficult urination). This is the basis for retrospective evaluation of group 1 patients as algic, gastrointestinal, sexual and pseudoneurological variants. Somatized symptomatology includes: painful sensations in at least 4 parts of the body; pain syndrome and pronounced functional disorders of the gastrointestinal tract (nausea, vomiting, inability to tolerate certain products); pain syndrome and functional disorders in the sexual sphere; pseudoneurological symptoms (paraparesis, incoordination, diplopia, something stuck in the throat, aphonia, difficult urination). This is the basis for retrospective evaluation of group 1 patients as algic, gastrointestinal, sexual and pseudoneurological variants (Table 3).Table 3. Types of somatized disorders in group 1 (n -84)

|

| |

|

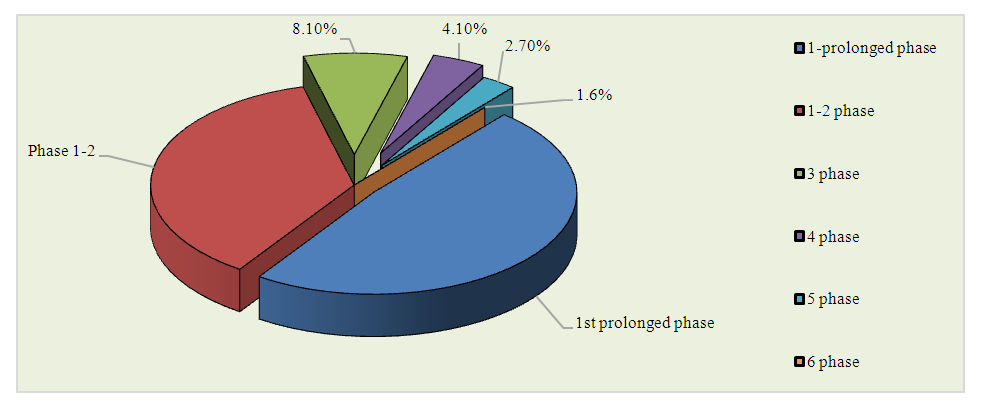

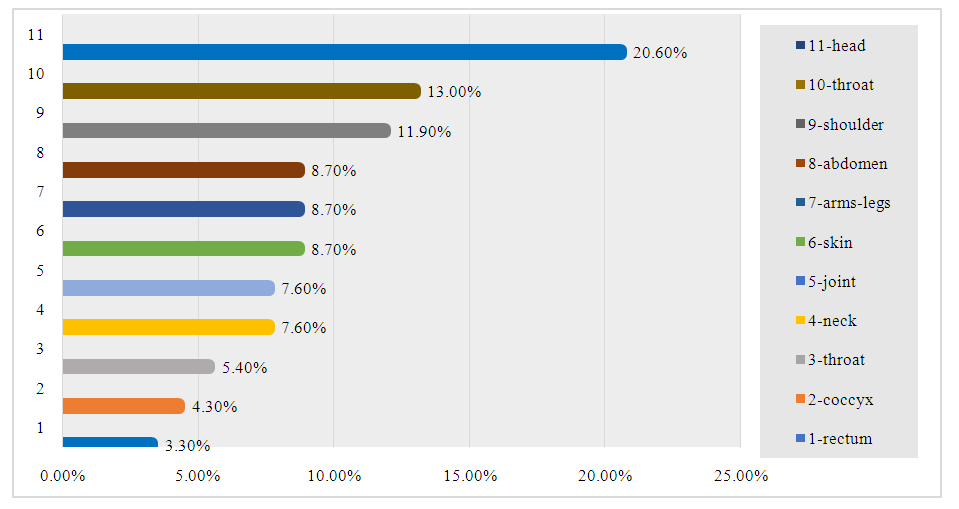

Group 1 patients, that is, somatized subdepressive patients, during the catamenesis, 4 variants of somatized disorders were identified (DSM-IV): algic-55 (65.5%) patients, gastrointestinal -16 (19.0%) patients, pseudoneurological-11 was observed in 1 (13.1%) patients, sexual - 2 (2.4%) patients.In the algic variant of somatized disorders, algopathies have 4 or more localizations in different parts of the body, in different organs. The sensory component of the algic variant of the somatized disorder was represented by algias in 76.1% of cases, and thermal senestopathies in 23.9% of cases. According to J. Glatzel (1967), this variant of subdepressive disorder is characterized by homonymous senestopathies, they are simple and understandable in structure. 34.8% of algopathies are generalized algias (4 or more localizations), 34.8% of algias are 3 or more localizations, combined with monolocal thermal senestopathies, 30.4% of algias are 2 localizations, combined with bilocal thermal senestopathies. The distribution of algopathies in the algic variant of somatized disorders across the body is presented in Figure 3. | Figure 3 |

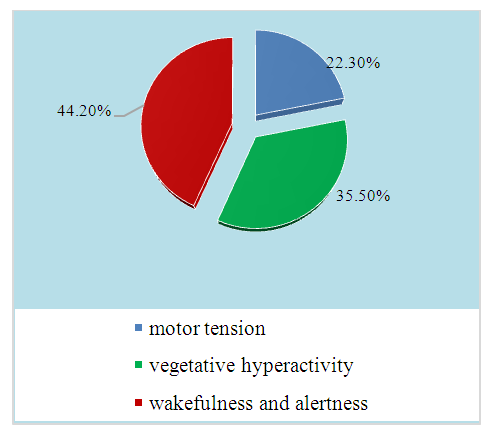

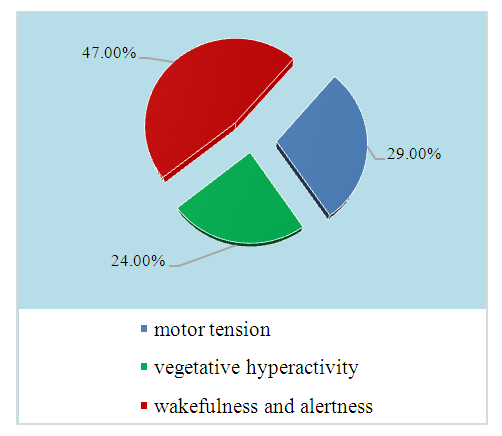

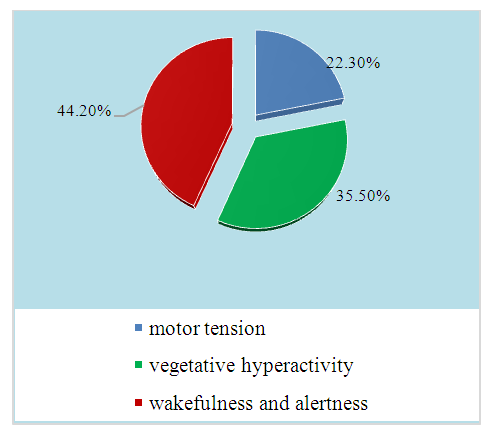

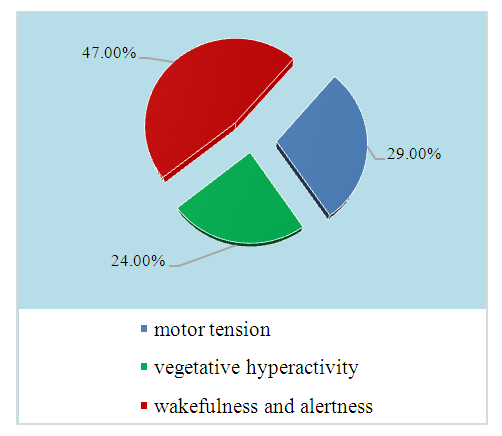

In the diagnosis of panic disorders allows us to identify obsessive panic attacks (non-hypochondriac and hypochondriac content), which is a reflection of mental panic, and helps to assess somatic and autonomic panic. According to DSM-III-R, generalized panic disorder (inadequate or extreme anxiety, prolonged anticipation of two or more life situations) is observed. Most of the patients of group 1 had generalized panic disorder (GVB) according to DSM-III-R. In this case, "alertness and vigilance" covered large levels (44.2%), "vegetative hyperactivity" (33.2%) and "activity" represented 22.3%. In patients of group 2, "alertness and vigilance" (47.0%), "vegetative hyperactivity" and "movement" were expressed at almost the same levels (24.0% and 29.0%) in GVB (Fig. 4-5). | Figure 4 |

| Figure 5 |

6. Conclusions

In the stability of somatized subdepressive disorders, in their progressive course, somatogenic provocations, hypochondriacal sticky panic attacks, presence of vegetodystonia syndrome, metotropic lability, residual cerebral insufficiency in the form of inability to tolerate hot, humid air were considered risk factors. In somatized subdepressive patients, the average number of hospitalizations in a psychiatric hospital during one year and five-year periods increased, and the length of periods between hospitalizations decreased from the second five-year period, observed with reliable signs. In non-somatized subdepressive patients, the average number of hospitalizations decreased slightly in the second five years and remained almost stable in the third and fourth five years.

References

| [1] | Adilay H. U. et al. The correlation of SCL-90-R anxiety, depression, somatization subscale scores with chronic low back pain. – 2018. |

| [2] | Anderson G., Berk M., Maes M. Biological phenotypes underpin the physio-somatic symptoms of somatization, depression, and chronic fatigue syndrome // Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. – 2014. – Т. 129. – №. 2. – С. 83-97. |

| [3] | Brown T.A., Barlow D.H. A proposal for a dimensional classification system based on the shared features of the DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders: implications for assessment and treatment // Psychol. Assessment. 2009. Vol. 21. N3. С.256. |

| [4] | Bukh J.D., Andersen P.K., Kessing L.V. Rates and predictors ofremission, recurrence and conversion to bipolar disorder after the first lifetime episode of depression – a prospective 5-year follow-up study // Psychol. Med. 2016. Vol. 46. N6. С. 1151–1161. |

| [5] | Canales G. D. L. T. et al. Distribution of depression, somatization and pain-related impairment in patients with chronic temporomandibular disorders // Journal of Applied Oral Science. – 2019. – Т. 27. |

| [6] | Clauwaert N. et al. Associations between gastric sensorimotor function, depression, somatization, and symptom-based subgroups in functional gastroduodenal disorders: are all symptoms equal? // Neurogastroenterology & Motility. – 2012. – Т. 24. – №. 12. – С. 1088-e565. |

| [7] | Conradi H.J., Ormel J., De Jonge P. Presence of individual (residual) symptoms during depressive episodes and periods of remission: a 3-year prospective study // Psychol. Med. 2011. Vol. 41. N 6. С. 1165–1174. |

| [8] | Dreher A. et al. Cultural differences in symptom representation for depression and somatization measured by the PHQ between Vietnamese and German psychiatric outpatients // Journal of Psychosomatic Research. – 2017. – Т. 102. – С. 71-77. |

| [9] | Dremencov E., Mansari M., Blier P. Noradrenergic augmentation of escitalopram response by risperidone: electrophysiologic studies in the rat brain // Biol. Psychiatr. 2007. Vol. 61. N 5. P. 671–678. |

| [10] | Edmond S. L., Werneke M. W., Hart D. L. Association between centralization, depression, somatization, and disability among patients with nonspecific low back pain // journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. – 2010. – Т. 40. – №. 12. – С. 801-810. |

| [11] | Fava M. et al. Clinical correlates and symptom patterns of anxious depression among patients with major depressive disorder in STAR* D // Psychol. Med. 2004. Vol. 34. N 7. P. 1299. |

| [12] | Fava M. et al. Difference in treatment outcome in outpatients with anxious versus nonanxious depression: a STAR* D report // Am. J. Psychiatr. 2008. Vol. 165. N. 3. P. 342–351. |

| [13] | Papakostas G.I., Fan H., Tedeschini E. Severe and anxious depression: combining definitions of clinical sub-types to identify patients differentially responsive to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors // Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012. Vol. 22. N 5. P. 347–355. |

| [14] | Ran L. et al. Psychological resilience, depression, anxiety, and somatization symptoms in response to COVID-19: A study of the general population in China at the peak of its epidemic // Social Science & Medicine. – 2020. – Т. 262. – С. 113261. |

| [15] | Robertson D. et al. Associations between low back pain and depression and somatization in a Canadian emerging adult population // The journal of the canadian chiropractic association. – 2017. – Т. 61. – №. 2. – С. 96. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML