-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2024; 14(4): 1040-1043

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20241404.49

Received: Apr. 2, 2024; Accepted: Apr. 16, 2024; Published: Apr. 19, 2024

Comparative Analysis of the Effectiveness of Combined Treatment of Osteogenic Sarcoma in Tubular Bones in Children

Iskandarov Kamol Zayniddinovich1, Islomov Sarvar Temurovich2, Sayitov Begali Shokir Ugli3, Rustamova Xilola Mirzakarimovna3

1Head of the Department "Oncology and Hematology", National Children's Medical Center, 294 Parkent street, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

2Scientific Researcher, Department "Oncology and Hematology", National Children's Medical Center, 294 Parkent Street, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

3Department "Oncology and Hematology", National Children's Medical Center, 294 Parkent street, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

Correspondence to: Iskandarov Kamol Zayniddinovich, Head of the Department "Oncology and Hematology", National Children's Medical Center, 294 Parkent street, Tashkent, Uzbekistan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

One of the most prevalent primary malignant bone tumours in children and adolescents is classical osteosarcoma. The metaphysis accounts for 90% of tumour localization in long tubular bones, with the diaphysis accounting for 9% and the epiphysis accounting for a very rare occurrence of tumours. The clinical, radiographic, and histological diagnosis of classical (conventional) osteosarcoma in children and adolescents is covered in this article. Genetic abnormalities, differential diagnosis, and the prognosis for this pathology are also briefly discussed.

Keywords: Osteosarcoma, Method, Diagnosis, Treatment, Children and adolescents

Cite this paper: Iskandarov Kamol Zayniddinovich, Islomov Sarvar Temurovich, Sayitov Begali Shokir Ugli, Rustamova Xilola Mirzakarimovna, Comparative Analysis of the Effectiveness of Combined Treatment of Osteogenic Sarcoma in Tubular Bones in Children, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 14 No. 4, 2024, pp. 1040-1043. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20241404.49.

1. Introduction

- Osteosarcoma is a malignant osteogenic tumor consisting of neoplastic cells that produce osteoid or a substance histologically indistinguishable from it in at least one visual field [1]. According to the WHO classification, there are several options:1. Central osteosarcoma (low-grade).2. Classic (conventional) osteosarcoma.3. Telangiectatic osteosarcoma.4. Small cell osteosarcoma.5. Secondary osteosarcoma.6. Paraosteal osteosarcoma.7. Periosteal osteosarcoma.8. Superficial osteosarcoma (high-grade).

2. Mаtеriаls аnd Mеthоds

- Classic osteosarcoma is an intraosseous malignant tumor whose cells produce bone. It is considered primary if it develops in unchanged bone, and secondary if it develops against the background of radiation, Paget’s disease, etc.Classic osteosarcoma is the most common high-grade primary sarcoma affecting bone [2]. Despite this, it accounts for less than 1% of all malignant tumors occurring in the US population [2,3]. The incidence rate is from 10 to 26 new cases per 1 million population of the planet per year [4]. Has a bimodal age distribution. The first peak is in the age group of 10-14 years, the second - at the age of over 40 years. It is extremely rare in children under 5 years of age [5]. Gender distribution favors the male population with a ratio of 1.35:1. As a result of malignant transformation, Paget's disease occurs in approximately 1% of cases, more often in patients with multiple bone lesions, with a peak in the 7th decade of life and accounts for up to half of all cases of osteosarcoma in patients over 60 years of age. Osteosarcoma is the most common radiation-induced sarcoma (2.7–5.5% of all osteosarcomas), most often in patients over 40 years of age. Less commonly associated with benign tumors and tumor-like bone lesions (fibrous dysplasia, simple bone cyst) and metal prostheses. In the study by L. Mirabello et al [3], primary osteosarcoma was 88%, secondary - 10%, and as a consequence of Paget's disease - 2%. Cases of secondary osteosarcoma in children after complex treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia and gamma/delta T-cell lymphoma have been described [2].

3. Rеsults аnd Disсussiоn

- The etiology of osteosarcoma is unknown. It occurs de novo without any predisposing factors. May appear after injury or foreign body (orthopedic implants) [1]. There is evidence of an increased risk of osteosarcoma in children with a birth weight of more than 4046 g and height above average [3]. It is believed to develop from a mesenchymal stem cell with minimal osteoblastic differentiation, but the “cell of origin” remains unknown [4]. It is observed more often among various genetically determined syndromes: Li-Fraumeni, congenital retinoblastoma, Rothmund-Thomson, Diamond Blackfan anemia, Bloom, Werner syndrome and others [5].May occur in various bones. However, more often in the long tubular bones of the extremities [3], especially in the distal part of the femur (30%), proximal part of the tibia (15%), and proximal part of the humerus (15%). These localizations are due to the greatest proliferation of the “growth plate”. In long tubular bones, the tumor is usually localized in the metaphysis (90%), less often in the diaphysis (9%) and extremely rarely in the epiphysis. Tumors localized in the jaws, pelvic bones and vertebrae are usually observed in older age groups. When the jaws are affected, the tumor is more common in the lower jaw than in the upper jaw (58 and 42%, respectively) [1]. Involvement of small skeletal bones in the pathological process is rare [2]. Multifocal lesions occur in Paget's disease in 15-20% of cases. However, the question still remains open whether this is a primary multiple or metastatic lesion.Clinically manifested by a progressive increase in the volume of the affected part of the body. The concern is deep, growing pain, sometimes for several weeks or months. The skin over the tumor may be hyperemic, edematous, with an accentuated venous pattern. In advanced cases, ulceration of the skin over the tumor is observed (Fig. 1).

| Figure 1. Classic osteosarcoma of the humerus with damage to the soft tissues of the shoulder and an extensive ulcerative skin defect. Boy, 9 years old |

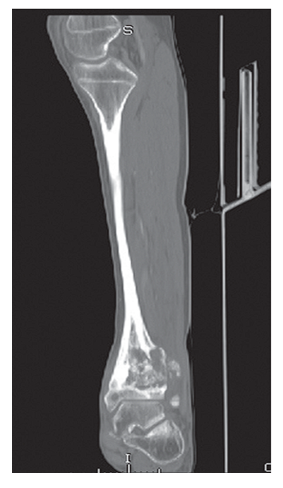

| Figure 2. Classic osteosarcoma of the distal epiphysis and metaphysis of the tibia. The destruction of the periosteum is determined, the soft tissue component of the tumor is clearly visible |

4. Соnсlusiоns

- The prognosis of osteosarcoma depends on many factors: age, gender, size (volume) of the tumor, location, cleanliness of the surgical resection margin and stage. For example, localized distal involvement of more than 90% of chemotherapy-induced tumor necrosis in combination with radical resection provides a 5-year survival rate of more than 80% of cases. For example, there are studies showing a correlation between the amount of tumor necrosis and prognosis [1], the level of VEGF expression with a worse prognosis and the possibility of using targeted therapy [2]. Some authors report a better prognosis if morphometric examination reveals “large and round” nuclei of neoplastic cells [3]. The prognosis is worse with proximal or axial localization of the tumor, large size, presence of metastases and poor response to preoperative chemotherapy, with tumor localization in the pelvic bones, deviation from the normal body mass index on the body. ment of diagnosis. There are reports on the relationship between the intensity of apoptosis of neoplastic cells and prognosis.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML