-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2024; 14(3): 669-674

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20241403.28

Received: Jan. 8, 2024; Accepted: Jan. 28, 2024; Published: Mar. 9, 2024

Essential Tremor in Children (Review of Literature)

Sadykova G. K.1, Adambaev Z. I.2, Mirjuraev Zh. E.1

1Tashkent Pediatric Medical Institute, Uzbekistan

2Urgench Branch of the Tashkent Medical Academy, Uzbekistan

Correspondence to: Adambaev Z. I., Urgench Branch of the Tashkent Medical Academy, Uzbekistan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Introduction. Essential tremor (ET) is one of the most common movement disorders in adults. ET in children has been little studied, which was the purpose of our study. Objective. We conducted a systematic review of the literature to comprehensively characterize the clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment of ET from a childhood perspective. Methods. A systematic review of literature published primarily in English between 1984 and 2022 was conducted. Results. 36 studies were selected for analysis. There was significant heterogeneity in study design, statistical approaches, and patient cohorts among the included studies. Information about the epidemiology, etiological aspects, diagnosis, stages and effectiveness of treatment for ET is provided. Conclusion. A systematic review of the literature allows us to conclude that essential tremor in children and adolescents is relatively less common than in adults; children are more likely to have a genetic predisposition to its development. The disease tends to gradually increase symptoms with age. There are some difficulties in differential diagnosis with other types of tremor. In children, due to their age and not quite pronounced tremor, there are no radical treatment methods leading to complete recovery. All this requires further research into essential tremor.

Keywords: Essential tremor, Essential tremor in children, Conservative and neurosurgical treatment, Systematic review of the literature

Cite this paper: Sadykova G. K., Adambaev Z. I., Mirjuraev Zh. E., Essential Tremor in Children (Review of Literature), American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 14 No. 3, 2024, pp. 669-674. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20241403.28.

Article Outline

1. Relevance

- Essential tremor (ET) is one of the most common movement disorders worldwide and occurs in approximately 1% of the world's population [1]. ET is defined as a syndrome of isolated tremor involving bilateral upper extremities, sometimes accompanied by tremor elsewhere for at least 3 years, which occurs in the absence of other neurological symptoms such as ataxia and parkinsonism [2].According to a literature review [3] 9 literature sources were identified, among 9 adult populations the age of onset of ET was described, which ranged from 27.0 to 56.7 years (weighted mean 41.6 years). In one adult sample, it was reported that 13% of all cases of ET developed by age 14 years, and 21.8% of all cases of ET by age 18 years. In this review, only one sample would report information on ET diagnosis among pediatric patients with a mean age of 9.7 years.A previously published US population-based analysis (using data collected between 1935 and 1979 in Rochester, Minnesota) found an age- and sex-adjusted incidence rate of ET of 23.7 per 100,000 (1965–79) and a prevalence of 305. 6 per 100,000 in the USA [4]. Among patients aged 0–19 years in this sample, the incidence rate was much lower, at 2.9 per 100,000 over the same period [3]. Studies from other countries have reported prevalence rates of ET in children that were very low or close to zero in the pediatric population [5,6].According to literature sources, the prevalence of ET increases with age. Thus, the prevalence of ET among adults was estimated at 2.6%; among people aged 65 years and older, this prevalence increases to almost 6% [7], and at the age of 85 years and older it is 8.2% [8]. Despite the fact that the prevalence of ET tends to increase with age, there are 2 age periods of onset of the disease - the second and sixth decades [9]. According to some researchers, the early peak of the onset of the disease may be predominantly due to familial (genetically predisposed) cases of ET, while the late peak – to sporadic cases of ET [9]. According to the same authors, up to 50% of familial cases of ET began before the age of 18 years.There is very little information on the prevalence of ET in children. Among rare studies in patients aged 0-19 years, the incidence rate was much lower compared to adults and was less than 1% [9].The prevalence of potential cases of ET in Turkish adolescents aged 14-18 years was 1.2% (n = 52/4330), ET - 0.41% (n = 18/4330). The ratio of boys to girls in ET was 5:1 (boys = 15 and girls = 3). ET cases were subclassified as follows: 10 (55.5%) overt ET, 3 (16.6%) probable ET, and 5 (27.7%) possible ET [10].A retrospective review study that examined children with ET deserves special attention. Of the 211 children with ET, the mean age at onset was 9.7 years, and the mean age at presentation was 14.1 years. Moreover, 13% of children indicated that they were not sure about the timing of the onset of the disease, while 29% reported the onset of the disease during the first decade of life and 57% in the second decade. The majority of patients (71%) did not require drug treatment for ET, and functional impairment associated with ET was not observed in the charts of 45% of all patients. None of the 211 children with ET showed any disability that would interfere with daily activities [11].

2. Etiology and Pathogenesis

- Essential tremor often runs in families with a typical autosomal dominant pattern. According to the relevant literature, family history is predominant and important for the diagnosis and clinical presentation of ET. In numerous studies, the diagnosis of ET in close relatives in the family averaged 50% [7]. To date, the existence of several independent genetic variants of ET has been established, which confirms the idea of the heterogeneity of this disease [12]. For some of the candidate loci that have been identified as responsible for the development of ET, promising candidate genes have been identified, however, these data are ambiguous [13].Recent reports link the genes LINGO1, FUS, TENM4, SLC1A2 and STK32B to ET [14,15,16,17].Thus, it has already been proven that ET is not a monogenic disease; however, insufficient knowledge of the etiological factors in ET does not allow the use of mutations and polymorphisms identified to date in clinical practice as diagnostic or prognostic criteria.

3. Clinical Manifestations

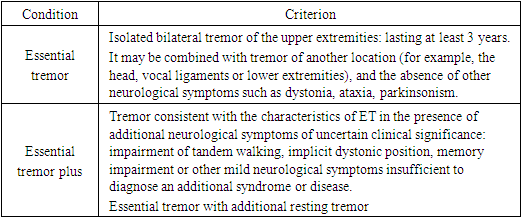

- The main clinical manifestation of the disease is bilateral action tremor in the hands, which appears during movement (kinetic tremor) and/or when voluntarily holding a certain position (postural tremor).Tremor usually appears in both hands at once or first in one, and then with a short delay (no more than several months) in the other, but its amplitude in one hand may be higher than in the other, so the symmetry of the tremors can be relative [18]. Moreover, in a number of familial cases (4.4%) with an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance, patients with both bilateral and unilateral tremor were observed. However, sporadic cases of unilateral action tremor are not usually classified as ET. Initially, the tremor involves the distal parts of the arms, then the trembling spreads in the proximal direction and to the axial parts (head, larynx, rarely torso).It is believed that ET is characterized by a benign, slowly progressive course [12], however, in 15% of cases it leads to severe disability [19]. It is worth noting that in more than 80% of patients who sought medical help, tremor caused difficulties in daily activities, for example, limiting the ability to eat or dress independently. About ¼ of patients who came to the diagnostic center were forced to leave work due to tremor [19]. We did not find any reports of disability in children due to ET in the literature.Tremors in the hands most often include flexion/extension of the hands, abduction/extension of the fingers, much less often it has a rotatory nature (pronation/supination), which is more characteristic of parkinsonian tremor. The oscillation frequency during ET is 6-10 Hz. As the patient's age increases, there is a tendency for the tremor frequency to decrease to 4 Hz.Head tremor is observed in approximately 30% of patients with ET [20]. Head shaking can be represented by a “yes-yes” or “no-no” oscillation.At a later stage, tremor involves the vocal cords (about 20% of cases), face/jaw (about 10%), tongue (about 20%), trunk (about 5%) and lower extremities (about 10%) [20]. Due to tremor of the tongue, soft palate, and vocal folds, patients may experience mild dysarthria, but it is rarely observed before 65 years of age.During the day, due to the daily rhythms of physiological processes and changes in the emotional state, fluctuations in the amplitude (but not frequency) of tremor are possible. Under the influence of stress, overwork, increased temperature, or taking psychostimulants, the severity of trembling may temporarily increase. Like other extrapyramidal syndromes, tremors decrease or disappear completely during sleep.With the classic version of ET, there are no other neurological manifestations, however, in the clinic there are often cases where trembling, similar to ET, is accompanied by other neurological symptoms. Among them are cerebellar (impaired tandem walking, intention tremor, dysmetria), dystonic symptoms (head posture, writer's cramp, blepharospasm), symptoms of parkinsonism (rest tremor, hypomimia, bradykinesia, tendency to achyrokinesis). These are usually “mild symptoms” that are not clinically significant, i.e. not reaching the degree of severity that allows diagnosing a particular neurological syndrome. In recent years, in such cases it has been customary to diagnose ET-plus [21]. The recently published diagnostic criteria for ET developed by the International Parkinson's Disease and Movement Disorder Society include the definition of ET-plus for the first time (see table).

|

4. Diagnostic Criteria for Essential Tremor

- In some patients with ET, in addition to kinetic-postural tremor, rest tremor is observed in the absence of rigidity or bradykinesia [22]. These patients have more pronounced and widespread postural-kinetic tremors. It should be taken into account that rest tremor during ET has some peculiarities, being only a continuation of pronounced postural-kinetic tremors, has the same frequency characteristics, and does not decrease with movement. In this regard, it is more correct to define this type of tremor as “tremor at rest.”Approximately 1/3 of patients with ET have impaired tandem walking, which may indicate cerebellar dysfunction [18]. In recent years, researchers have been particularly interested in studying non-motor manifestations in ET.In many studies [19] with ET, moderate cognitive impairment was detected. The profile of cognitive impairment suggests possible dysfunction of the frontostriatal or cerebellar-thalamocortical systems. In addition, a connection was established between cognitive impairment and late onset of the disease and the severity of dementia: at the onset of the disease at the age of 65 years, 70% of patients had a cognitive defect [19]. However, we did not find cognitive impairment in ET in children in the literature.

5. Diagnostics

- The issue of neurodiagnosis of ET is complex, especially in children. However, several lines of evidence point to cerebellar dysfunction. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy showed decreased levels of N-acetyl aspartate in the cerebellum, indicating neuronal dysfunction. Some of the pathological studies showed loss of Purkinje cells in the cerebellum; γ-aminobutyric acid dysfunction has also been reported in the cerebellum of people with ET. The pathophysiology of ET involves rhythmic activity in the cortical-pontocerebello-thalamo-cortical loop, although the origin of the oscillations is unknown. Cerebellar metabolism is high at rest, increases with arm extension, and decreases with ethanol (which suppresses ET).The following diagnostic criteria are used to diagnose ET [23].Main criteria:• Bilateral action tremor of the hands and forearms (but not resting tremor);• No other neurological symptoms other than cogwheel;• There may be isolated head tremor without signs of dystonia.Secondary criteria:• Long term (> 3 years);• Positive family history;• Favorable response to alcohol.Primary exclusion criteria:• Other abnormal neurological signs or history of recent neurological trauma preceding the onset of tremor;• Presence of known causes of increased physiological tremor (drugs, anxiety, depression, hyperthyroidism);• History of psychogenic tremor;• Sudden onset or stepwise progression;• Primary orthostatic tremor;• Isolated tremor depending on position or task, including occupational tremor and primary written tremor.For the differential diagnosis of ET, magnetic resonance imaging of the brain is performed and the levels of serum copper (Cu), ceruloplasmin, T3, T4 and thyroid-stimulating hormone are measured.Secondary exclusion criteria:• Abnormal test result(s).

6. Treatment

- The goal of treatment for ET is to minimize functional limitations associated with tremor and reduce social maladjustment. Therapy may include physical therapy, behavioral psychotherapeutic interventions, lifestyle changes, medications and surgery. ET therapy is symptomatic and does not cure, prevent or slow the rate of disease progression. In cases where the patient does not have functional or psychosocial impairments, no treatment is required [19].In a significant number of cases, especially at an early stage, drug treatment is not required: it is enough to reassure patients, who often experience discomfort not so much due to the tremor itself, but rather due to fears about the expected onset of a severe disabling disease (most often Parkinson's disease).Most patients with moderate tremor are able to minimize functional and social disability by mastering adaptive techniques: using pens, knives or eating utensils with comfortable thick handles, scissors with safety blunt ends, a voice-controlled telephone, etc. Methods of physical influence include the use of special orthoses, which can be used to limit the range of motion of the wrist joint [24].In cases where tremor leads to limitation of professional or household activities, drug treatment is indicated, the choice of drugs for which is carried out taking into account their expected safety and effectiveness. The safest and most effective medications (level of evidence A), according to the expert committee of the American Academy of Neurology include the β-blocker propranolol and the anticonvulsant primidone. Primidone and propranolol are the cornerstones of supportive drug therapy for essential tremor. These drugs give a good effect, reducing the amplitude of tremor in approximately 50–70% of patients [25]. Second-choice drugs (level of evidence B) include alprazolam, sotalol, atenolol, gabapentin, topiramate. Benzodiazepines and GABAergic drugs – Gabapentin and clonazepam are almost equally effective in the short term. However, due to concerns about drug dependence with long-term use of clonazepam, gabapentin is the drug of choice in this class [26].Injections of botulinum toxin A for the treatment of ET are indicated in cases resistant to conservative treatment, more often with severe tremor of the head and voice. It should be taken into account that the use of botulinum toxin to treat voice tremors may cause problems with breathing, articulation and swallowing. The effectiveness of botulinum toxin A in the treatment of limb tremors in ET is usually moderate and is often accompanied by dose-dependent weakness of the wrist extensors. To maintain the effect, repeated injections are necessary after 3-6 months [27].In the most severe cases of hand tremor that are resistant to pharmacological treatment, stereotactic intervention is used on the ventral intermediate nucleus of the thalamus: implantation of electrodes on one or both sides followed by chronic stimulation or thalamotomy [28]. Surgery may include deep brain stimulation (DBS) or magnetic resonance-guided focused ultrasound (MRgFUS) thalamotomy. DBS has demonstrated a strong therapeutic effect [29,30,31], however, possible complications associated with DBS have been noted, including intracranial and intracerebral hemorrhage, infection and malposition of DBS, paresthesia, headache, dysarthria, dyskinesia and ataxia [32]. Moreover, the invasive nature of DBS influences patients' decisions to undergo treatment.Stimulation is not indicated for the treatment of axial tremor (head and vocal cords). With asymmetric tremor on the corresponding side, thalamotomy is possible, but on both sides, due to the risk of side effects, it is not allowed. There is insufficient evidence for the long-term effectiveness of gamma knife thalamotomy.A promising neurosurgical method in the treatment of ET is ultrasound thalamotomy under MRI control. Due to the high prevalence of essential tremor, diagnostic difficulties and the lack of complete medical correction of the pathology, unilateral thalamic thermal ablation using focused ultrasound under visual control of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has begun to prove itself at the present stage, which has contributed to a significantly greater reduction in hand tremor and improvement quality of life over 12 months [33,34,35]. However, cost and potential side effects limit the usefulness of this treatment for ET [36].It should be noted that in children with ET the severity of tremor is low and it does not have disabling consequences, therefore surgical and neurosurgical interventions for ET are not carried out and we have not found them in the literature.

7. Conclusions

- A systematic review of the literature allows us to conclude that essential tremor in children and adolescents is relatively less common than in adults; children are more likely to have a genetic predisposition to its development. The disease tends to gradually increase symptoms with age. There are some difficulties in differential diagnosis with other types of tremor. In children, due to their age and not quite pronounced tremor, there are no radical treatment methods leading to complete recovery. All this requires further research into essential tremor.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors are grateful to: Mirjuraev Zh.E. for collecting and analyzing literary sources for writing the article, Adambaev Z.I. in writing the article, Sadykova G.K., in the correction of the article. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest when writing this article. The publication is funded from its own funds.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML