-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2024; 14(2): 514-516

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20241402.71

Received: Feb. 9, 2024; Accepted: Feb. 25, 2024; Published: Feb. 27, 2024

Electromyographic Study of Muscles in Patients with Epilepsy

Makhmudov M. B., Salimov O. R., Akhmedov M. R.

Tashkent State Dental Institute, Uzbekistan

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This study investigated the electromyographic activity of masticatory and facial muscles in 37 epilepsy patients and 18 healthy individuals. Results indicated significant impairment in muscle function among epilepsy patients, influenced by the disease's form, tooth loss, and dental arch defects. Findings underscore the importance of considering electromyographic results in treatment decisions for epilepsy patients, especially in dental care planning. The study highlights alterations in the balance between excitatory and inhibitory processes in muscle function, along with disruptions in bioactivity phases. These findings emphasize the necessity of tailored dental care strategies for epilepsy patients to address their specific oral health needs.

Keywords: Epilepsy, Electromyography, Masticatory muscles, Dentition defects

Cite this paper: Makhmudov M. B., Salimov O. R., Akhmedov M. R., Electromyographic Study of Muscles in Patients with Epilepsy, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 14 No. 2, 2024, pp. 514-516. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20241402.71.

1. Introduction

- Pathological processes in the tissues of the oral cavity become foci of chronic infection and, by disrupting many functions of the stomatognathic system, lead to impaired function of internal organs and exacerbation of chronic diseases. As a result, a persistent vicious circle is formed in the body of such patients.One of the most serious and ancient disorders that impact people is epilepsy. In epileptic patients, seizures dramatically change the central nervous system's (CNS) functioning condition. It's critical to keep in mind that during seizures, CNS fatigue may be building. [3,4]. Patients suffering from epilepsy often experience dental caries affecting the stomatognathic system, as well as disruption of the integrity of dental arches and teeth due to mechanical, chemical, thermal, and other factors related to both dietary habits and medical treatment. Consequently, the function of the masticatory apparatus is compromised in epilepsy patients, and the majority of them require dental prosthetic treatment.But while creating dental prostheses and performing other dental procedures, the previously described qualities of the prosthetic bed's organs and tissues are frequently disregarded. [5,6].It is crucial to address these issues and consider the unique challenges presented by epilepsy in dental treatment planning to ensure the best possible outcomes for patients. Additionally, incorporating preventive measures and tailored dental care strategies can help mitigate the impact of epilepsy-related dental issues on overall oral health and quality of life.

2. Materials and Methods

- Electromyography was used to examine the masticatory and face muscles in 18 virtually healthy people and 37 epileptic patients. The bioelectrical activity of the masticatory muscles was observed during intentional chewing, maximal contraction of the muscles, and rest. Based on the state of their dental arches, all epilepsy patients were split into two groups: those with intact dental arches and those with defects in their dental arches made up the first group.

3. Research Results

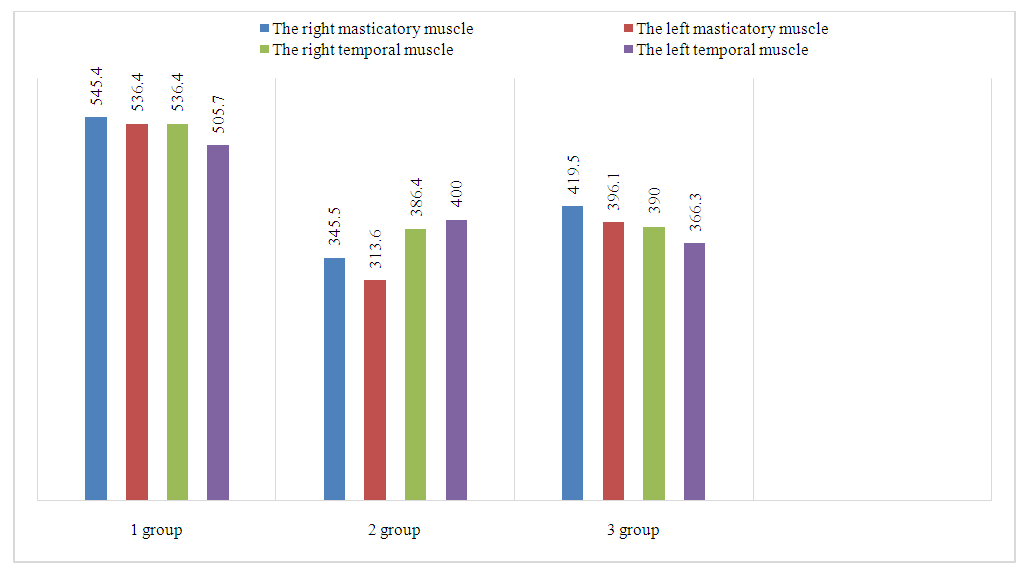

- The study's findings demonstrated that the amplitude at rest ranged from 5 to 10 μV in essentially healthy people with minor abnormalities and intact dental arches. The amplitude of the masseter muscles on the right side was 493.1 ± 26.3 μV, and on the left side it was 505.7 ± 31.9 μV. These values were obtained during maximal contraction in individuals with intact dental arches. The masticatory muscles of the right Temporalis were 545.4 ± 38.7 μV, while the left Temporalis was 536.4 ± 31.2 μV. The maximum contraction amplitude in the control group's members who had partial dental arches defects was as follows: for the masticatory muscles, on the right side it was 419.5 ± 32.4 μV, and on the left side it was 396.1 ± 27.5 μV; for the temporalis muscles, on the right side it was 390.0 ± 21.9 μV, and on the left side it was 366.3 ± 20.5 μV (Figure 1).

| Figure 1. Electromyographic examination during maximum contraction |

4. Conclusions

- Thus, based on the conducted electromyographic studies of the masticatory and temporalis muscles in epilepsy patients, significant impairment of their functional state has been established. This impairment is determined by the form of the disease in combination with tooth loss and the extent of dental arch defects. Consequently, there are alterations in the balance between excitatory and inhibitory processes of muscle function, an increase in the contractile ability of masticatory and temporalis muscles, disruption of the phase of bioactivity and bioelectrical rest. Additionally, changes in the symmetry of masticatory muscle function are noted.The results of electromyographic studies of the masticatory and temporalis muscles in epilepsy patients should be taken into account when choosing orthopedic dental tactics for prosthetic treatment in this patient population.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML