-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2024; 14(1): 69-74

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20241401.16

Received: Dec. 24, 2023; Accepted: Jan. 10, 2024; Published: Jan. 12, 2024

Dental Examination of Deaf-Mute Children: Experience and Research Results in Bukhara Region

Yuldashev Farrux Farxod Ogli1, Quryozov Akbar Quramboyevich2, Khabibova Nazira Nasulloevna3

1Independent Researcher of Bukhara State Medical Institute, Uzbekistan

2Associate Professor of Urganch Branch of Tashkent Medical Academy, Uzbekistan

3Professor of Bukhara State Medical Institute, Uzbekistan

Copyright © 2024 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The article presents the results of a cross-sectional study conducted at the Dental Department of the Bukhara State Medical Institute, the purpose of which was to assess the oral health and treatment needs of children with hearing and speech impairments. The study involved 124 students from two specialized boarding schools in the Bukhara region, including 78 boys and 46 girls in the age range from 6 to 18 years with an average age of 12.95 years. Particular attention was paid to the study methodology, including conducting a pilot study on 30 children to test questionnaires and clinical examination methods. The study results provide valuable data on the oral health status and need for dental intervention in this unique group of children, highlighting the importance of a specialized approach in pediatric dentistry.

Keywords: Children, Hearing impairment, Speech impairment, Oral health, Dental examination, Treatment needs

Cite this paper: Yuldashev Farrux Farxod Ogli, Quryozov Akbar Quramboyevich, Khabibova Nazira Nasulloevna, Dental Examination of Deaf-Mute Children: Experience and Research Results in Bukhara Region, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 14 No. 1, 2024, pp. 69-74. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20241401.16.

1. Introduction

- Oral health, being part of general health, influences the overall well-being of a person [1]. Oral and dental diseases affect various aspects of quality of life, and oral diseases can have a particularly negative impact on the overall health of people with certain systemic problems or conditions [2]. The Director-General of the World Health Organization rightly stated in 2000 that all people should be equal in matters of health, but people with disabilities have historically faced discrimination. Their participation in public life and social events is limited, which needs to change [3].A child with a disability can be defined as a person who, because of his or her disability, is limited from full participation in normal activities for his or her age [4]. According to 2018 WHO estimates, approximately 466 million people worldwide suffer from hearing loss, of which 34 million are children [5]. In India, according to the 2011 census, more than 3 million people have hearing loss and more than 1.2 million people have speech disabilities [6]. The consequences of hearing loss include the inability to interpret speech sounds, resulting in decreased ability to communicate, delays in language acquisition, economic and educational inequality, social isolation and stigma [7]. Visual impairment includes both low vision and blindness; blindness is defined as visual acuity less than 3/60 or a corresponding reduction in visual field to less than 10 degrees in the better eye with the best possible correction [8]. There are approximately 6 million visually impaired people in India out of 38 million blind people in the world [9].Oral diseases can have a direct and devastating impact on the health of people with certain systemic diseases or conditions [10]. Dental care is the most common unmet health care need among children with disabilities. It has been noted that dental treatment is the most underserved medical need of people with disabilities, as their families are so emotionally, physically and financially involved in the patient's medical condition that they find it difficult to focus on dentistry [11]. Consequently, cost of treatment, accessibility of facilities, fear of disease, acceptability of dentistry, and children's and parents' perception of the need for dental care are barriers to receiving dental care [12].Deaf, mute, and blind children with special needs are at increased risk for developing oral health problems and present unique challenges in managing their dental care. Therefore, it is necessary to develop an effective pre-planned primary prevention approach with the primary goal of alleviating and preventing diseases in our society by primary care providers [13]. These children are observed to have relatively poorer oral hygiene and an increased prevalence of gum disease and dental caries. Effective assessment of their oral health needs can enhance their primary health care, which is considered the foundation of an effective health care system, including accessible and affordable oral health outcomes. Therefore, the present study is conducted to assess the oral health status, treatment needs, knowledge, attitude and oral hygiene practices of deaf and mute children in Bukhara region.

2. Materials and Methods

- A cross-sectional study was conducted to assess the oral health status and treatment needs of children with hearing and speech impairments at the Dental Department of the Bukhara State Medical Institute.The study was conducted among the population of the Bukhara region, where there are two schools where deaf and dumb children are educated. All children registered in these schools were screened and the sample size was 124 children, of which 78 were boys and 46 were girls. A pilot study was also conducted on 30 children to determine the feasibility and applicability of the questionnaire and clinical examination.Permission to conduct research with these children was obtained from the parents of the observed children. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Republic of Uzbekistan and the Supervisory Board of the Bukhara State Medical Institute. Before the clinical examination of the study participants, informed consent was obtained in the state or Russian language from the directors of the respective schools.QuestionnaireA structured questionnaire was designed to collect information on demographics, dietary habits, sugar exposure, knowledge, attitudes and oral hygiene practices. All questions were explained in the children's native language, and the answers were recorded by the examiner himself.Clinical examinationThe oral health status and treatment needs of all children were assessed according to the WHO Oral Health Assessment Form (1997) [14]. Children sat upright in a chair and were examined in ample natural daylight using Type III examination. The examination was carried out using a dental speculum and a Community Periodontal Index (CPI) probe, and the instruments were sterilized in an autoclave before examination of the children.Statistical analysisData were analyzed using SPSS v16.0 software package. Cohen's kappa statistics were used to assess examiner reliability. Descriptive statistics such as mean, standard deviation and percentage were used for analysis. Associations were assessed using the chi-square test. Any P value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

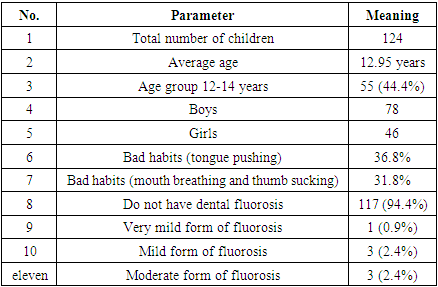

- Table 1 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants. The study was conducted among 124 schoolchildren aged 6 to 18 years with hearing and speech problems, with an average age of 12.95 years. Of the 124 children, the majority, 55 (44.4%), were in the age group of 12-14 years.

|

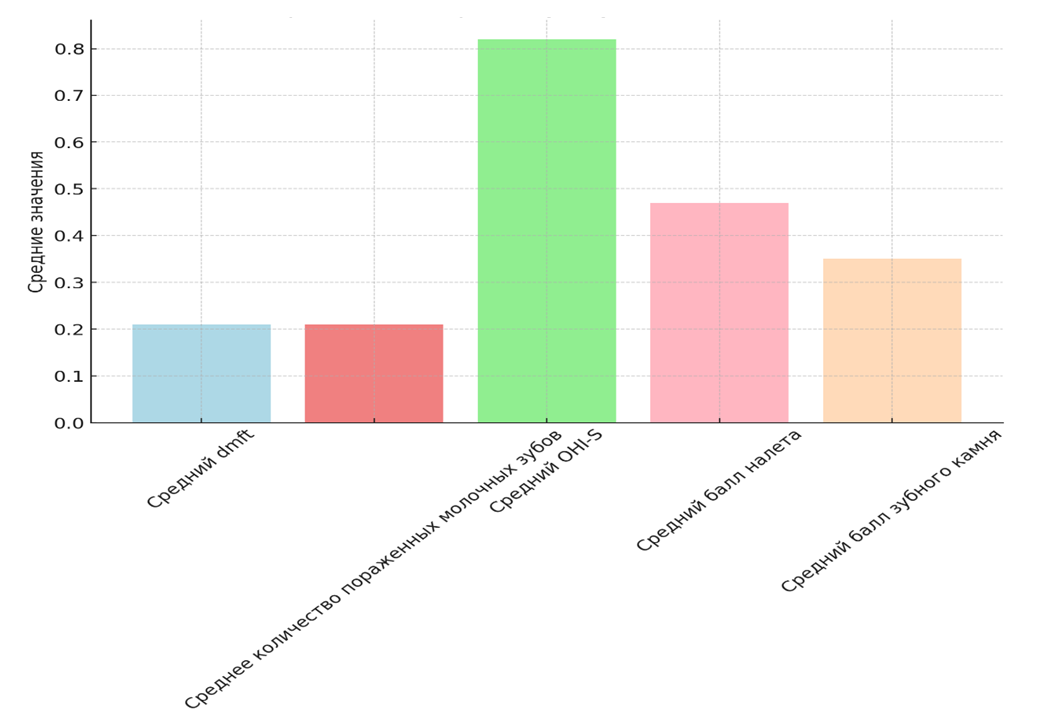

| Figure 1 |

| Figure 2 |

|

|

4. Discussion

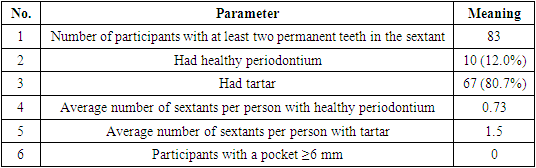

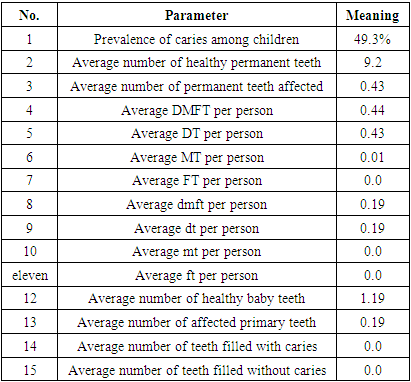

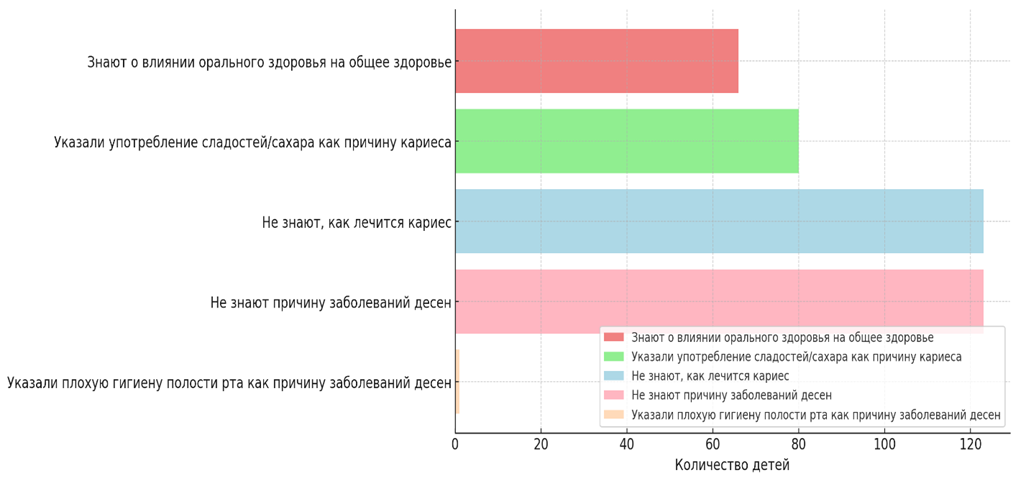

- Oral health is an integral part of overall health and well-being. People with special needs have the same rights to good oral health as everyone else in the country. Unfortunately, due to their condition and lack of awareness of oral health, dental diseases in these children often go undiagnosed, leading to a high unmet need for dental care [16]. With this in mind, the present study was conducted to assess the oral health status and treatment needs of deaf, mute children in Bukhara region.The key to good oral health is maintaining good oral hygiene habits, which should be practiced from childhood. In our study, the majority, 85.7% of deaf and mute children, used a toothbrush, while 14.3% brushed their teeth with their fingers. This is similar to the results of another study conducted among deaf and mute children in Russia, where 85.3% used a toothbrush to brush their teeth, and 14.67% used their finger [17]. Opposite results were found in another study in Inliya, where 97.37% of children used a toothbrush to brush their teeth, which may be due to greater awareness of oral health in more developed sections of society [18].Dental fluorosis was found in 5% of study participants, which is consistent with the results of a study conducted in Kuwait among disabled children and young adults, where 10% of study participants suffered from dental fluorosis [19].In our study, in children with hearing and speech impairments, dental calculus was detected in 78.5%. These data coincide with the results of another study conducted among adolescents with special needs in India, where 96% of children had hearing and speech impairments - 91.7% [20]. A similar study conducted in Delhi and Gurgaon found a high prevalence of poor gum health among deaf participants at 71.5% and among deaf participants at 49.6% [21]. The mean number of healthy sextants in our study was 1.75, which is consistent with the results of a study conducted in Udaipur, where the mean number of periodontally healthy sextants was 3.02 (±2.39). The average number of sextants with a stone in our study was 3.59, in contrast to the Udaipur study, where the average number of sextants with a stone was 0.51 (±0.98) [22]. Thus, our study showed a higher prevalence of periodontal disease at 87.4%, in contrast to the Udaipur study, where the prevalence of periodontitis was 67% [22]. Poor periodontal health was also found to be more common in children with hearing and speech impairments (83%), which may be due to difficulties in maintaining oral hygiene in these children, which in turn could exacerbate the effects of periodontal hormones.According to previous reports, current results indicate that children and adolescents with hearing loss can learn and perform oral hygiene practices as well as any other child, provided their caregiver is knowledgeable about the possible limitations that may arise [23]. The physician must get to know his patient and adapt his behavior and techniques to the patient's unique needs.Similar results were found in a study in South Canara, Karnataka, where the average DMFT score for deaf and dumb children was 2.6. This may be due to poor oral health in these children. Thus, poor oral health combined with poor oral hygiene practices increases the risk of dental caries. In another study conducted in Birmingham, UK, the mean DMFT score for a group of deaf and mute children was 1.76, which is higher than the results of this study.In this study, it was noted that 36.3% of children required superficial fillings, 4.2% of children required a crown for any reason, 2% of children required pulp therapy and restoration while only 1% of children required extraction tooth These results contrasted with another study conducted among children with disabilities. Lack of understanding of good oral hygiene practices among participants, low motivation, low priority of dental health in society, lack of initial and regular oral health monitoring and timely treatment, poor socio-economic status of parents or guardians and cost of treatment may be factors contributing to the accumulation of therapy needs.A dental education program should also be established, especially for educators, so that they can educate deaf and dumb children, impart to them the importance of oral health, and ultimately help them achieve the goal of dental wellness. In this study, the oral health of children with hearing and speech impairments was found to be at a fairly high level. Thus, better oral health in deaf and mute children may be associated with their ability to evaluate their oral hygiene, esthetics, and oral hygiene measures and practices more effectively. Since there are not many studies on the oral characteristics of children and adolescents with hearing impairments, it is suggested that additional studies such as the present one be conducted to obtain a general understanding of the oral characteristics of children and adolescents with hearing impairments.

5. Conclusions

- Children with hearing and speech impairments have been found to have a higher prevalence of dental caries, poorer oral hygiene status, a greater risk of poor periodontal health, and a significant unmet need for dental treatment compared to healthy children• Children with special needs are often neglected and given less priority in treatment, highlighting the need to improve access to oral health services for them.• Further efforts should be directed toward improving oral health education for children with disabilities, educating parents of such children regarding oral health care, and increasing the use of topical fluoridation and other effective methods of caries prevention.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML