-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2023; 13(12): 2045-2047

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20231312.48

Received: Dec. 6, 2023; Accepted: Dec. 23, 2023; Published: Dec. 28, 2023

Teaching Writing Style for Medical Students

Sharipova F. I. , Tolipova Sh. Sh. , Davletyarova N. I., Zakhidova M. F.

Tashkent Pediatric Medical Institute, Uzbekistan

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Writing style in the form of scientific thesis or articles can be challenging for medical students, studying medical English writing and it is especially so for postgraduate medical students, making a research at the of study in the institute. Although medical English language differs from everyday language, it requires more academic in the writing style. Even English language learning program curriculum in Uzbekistan has very little about how to support medical students with writing of academic scientific papers during making a research or experiment at the end of postgraduate course, in our case in the Tashkent Pediatric Medical Institute. Therefore, we organized our research to identify effective academic writing style for medical students, those who are postgraduate. We analyzed their academic writing skills according to purpose, participants, dependent factors, and conclusions. Then, we found out that academic writing style in the postgraduate works of medical students could be improved by academic and linguistic indicators. Analyses of the experiment showed that medical students (regard to the degree and course of the study) who were taught with academic writing style according to our research factors showed progress. The given research shows that the medical students' writing style of their diploma work for a scientific report presentation or in a scientific journal publication. Thus, our research results provide necessity of inclusion of medical students’ writing style research and academic skills development for medical students.

Keywords: Writing style, Medical students, English language, Postgraduate course, Diploma work

Cite this paper: Sharipova F. I. , Tolipova Sh. Sh. , Davletyarova N. I., Zakhidova M. F. , Teaching Writing Style for Medical Students, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 13 No. 12, 2023, pp. 2045-2047. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20231312.48.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The writing syle has a prominent role in higher education and employment [1]. Moreover, writing helps individuals reflect and evaluate their understanding [2]. In recent years, it has not only been used to promote communication skills but also to develop writing knowledge [3].Writing is complex, requiring spontaneous coordination of content, mechanics, and organization and is a learned skill that matures only with instruction and practice [4,5]. The fact that many students struggle with writing is therefore not surprising, and evident in our institute assessments of postgraduate students diploma 2022 report. According to this report, only 27% of postgraduate students achieved proficiency in writing (Tashkent Pediatric Medical Institute, Foreign languages department report, 2022). The cognitive load when writing often overwhelms medical students with low English language background and foundational writing skills (Tashkent Pediatric Medical Institute, Foreign languages department report, 2022). Only 2% of medical students of the Tashkent Pediatric medical institute scored at or above a proficient level in the State English language Exam (Tashkent Pediatric Medical Institute, Foreign languages department report, 2022). The ability to write well is important in science, yet we lack information about how to teach medical students to become proficient writers, especially with respect to expressing conceptual understanding in medicine. Through our study, we aimed to identify and compare approaches to medical writing style. We hypothesized that a combination of sociolinguistic and scientific approaches would likely be beneficial, because medical students are likely under-identified in studies due to many factors, such as limited description of participants in some studies, and the shared challenges that these target groups face when writing. In addition, we hypothesized that effective instructional directions of teaching English writing style would be effective for postgraduate medical students, based on what we know about their specific learning needs and what has been done in previous studies.

2. Materials and Methods

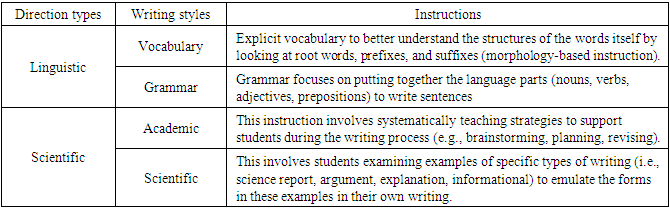

- We identified studies for systematic review using a multistep process following Cooper and Hedges’ [6] guidelines as follows. First, we looked for writing interventions in a science-learning context. Second, at least one outcome variable measured writing style (e.g., writing quality, genre knowledge) or used writing to demonstrate learning (e.g., a science test with short or long responses). Third, we focused on medical students because medical science writing style is different from actual scientific writing. We conducted the search using multiple research databases like Education Source, PsycINFO, and ProQuest and looked for studies published between 1987 and 2019. Different combinations of the following descriptors guided the search: writing style, English language, medical student, science writing, and science education. We derived the following codes based on the type of instructional supports that were present in our sample: direction types, writing styles, vocabulary instruction, grammar instruction, study of exemplar texts and opportunities for practice, and modeling. Then summarized these codes in three categories: (a) linguistis, (b) scientific direction types. Procedural facilitation, modeling, and providing students with opportunities for practice occurred in studies with all learner subgroups, so we categorized them as general writing supports. Table 1 provides information on instructional components in each study. This research study was conducted at the Tashkent Pediatric Medical Institute during one semester with postgraduate students of various specialties. Disciplines taught: for masters and PhD students - "Practical English". A total of 30 people took part in the research. The research methods were the analysis of students' written diploma works, observation, survey (questionnaires, essays on a given topic).

|

3. Results

- Our sample included studies with medical students who are Master degree, where the most medical students predominantly spoke Russian as a first language. About 2% of students had certificates of IELTS 6.0; the other half specified no any English language certificates. Explanations typically focused on describing mechanism(s) causing a given phenomenon. In our studies, students wrote diploma works after carrying out investigations that required them to test hypotheses and collect evidence in response to scientific questions. In these studies, students wrote diploma works using argumentative text structure (e.g., claim, evidence, reason, conclusion). During the research study the medical students, that are on the postgraduate course of the Tashkent Pediatric Medical Institute received systematic scientific education (i.e., strategy instruction), received some combination of general supports in all studies, but they rarely received linguistic supports like vocabulary or grammar instruction, or the study of exemplar texts. Students at Master degree received few specific approaches: linguistic direction occurred once, and scientific support was never provided. The use of lab reports and argumentative writing including questions for sections that are traditionally used in laboratory reports: (a) questions or hypothesis, (b) tests or procedures, (c) observations, (d) claims, (e) evidence, and (f) reflection was most common for medical students, that are on the postgraduate course of the studies. Most students received explicit instruction on the text structure, vocabulary, and grammar instruction. Improvements in the quality of informational texts were reported in the exams and discipline sessions. For example, the department of Foreign languages found that postgraduate students who had intermediate exams wrote higher quality arguments (d = 0.41). Furthermore, students were able to generalize learned skills when writing arguments about topics that were not taught during the intervention (d = 0.57). From 2022 summer diploma representation for Master degree students findings, it appears students who had multiple opportunities to practice using vocabulary while adopting appropriate grammatical structures demonstrated improvement in students’ overall writing quality. However, some students wrote descriptions rather than arguments even after intervention. In sum, these findings demonstrate mixed results for organizational quality, clarity, and overall scientific reasoning.

4. Discussion

- As for the students' written diplomawork itself, it have become more structured and stylistically coherent. Of course, it is premature to claim that there are fewer grammatical errors in the papers, although the tendency to regular work on errors is evident. This gives hope that over time the learner will make such work will become a rule.We had several purposes for this review, initially determining the types of learners and writing tasks in the science writing intervention literature with medical student. We then explored whether researchers embedded recommended instructional supports from prior reviews [7]; and finally, we determined the effects these supports had on students’ written language outcomes. Three major conclusions were drawn from the findings, which relate to differences in (a) tasks provided to learners based on education degree and English language background, (b) prevalence in instructional element use based on writing style focus, and (c) type of learning outcomes associated with task complexity and choice of dependent measures. Taken together, these recommendations provide clear guidelines for the types of writing style that should be given to struggling students in medical high schools. Our first main conclusion is that tasks provided to learners varied based on type of learning challenge and their background, or developmental levels. We also found that meaningful purposes and tasks were more likely to be given to high education degree students (who were more likely to write explanations, arguments, laboratory reports). Such tasks require justification of claims with analysis of scientific ideas or causal connections between variables. In contrast, tasks given to bachelor students focused primarily on genres such as writing informational reports. Our second conclusion is that the type of instructional elements used in interventions appears related to the education degree to which medical students belonged. Although students received at least support in all but our studies (with modeling, multiple opportunities for practice and procedural facilitation commonly occurring), we found interesting patterns. The medical students generally received little systematic cognitive or linguistic supports. Instead, they were given procedural facilitators (i.e., prompts or directions) to plan and organize their writing without modeling. Our third conclusion is that the benefits from these interventions are associated with task complexity and choice of dependent measures. To illustrate, MD students were more likely to receive strategy instruction than bachelor students, and those who did, demonstrated larger effect sizes on general writing outcomes such as organizational quality. Furthermore, postgraduate students benefited from text structure, surprisingly, writing gains for graduate students were less consistent across studies. Although they generally made gains in target areas such as vocabulary or science reasoning, not all made gains in disciplinary writing skills in science. The variability in findings may be due to differences in the intervention, but we cannot rule out the differences in the dependent measures. To be effective, teachers must first examine, analyze, and understand the language expected in the science curricula. Science teachers might include a mini-lesson on text structure, domain-specific vocabulary words, and teach specific linguistic features that define science writing.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

- One of the primary reasons for our review was to identify medical writing style that focuses on the cross-cutting concepts. Our review shows that effective cognitive writing supports [8] were often evident in the science writing style; however, even when present, the language supports did not sufficiently address the language needs. Even more important, it appears that medical students are not always asked to focus on disciplinary or scientific reasoning when asked to write in science. On one hand, it is understandable that some students in these groups need and benefit from instruction that focuses on domain-general tasks such as using writing to demonstrate knowledge of science content. On the other hand, our results also indicate that if high medical schools do not routinely employ both cognitive and linguistic elements in their instruction, these students may not learn to grasp aspects of scientific language. We suspect that many medical postgraduate students are not provided with medical writing style that are centered on the disciplinary demands of science—they are not learning to practice scientific argumentation, at least when judged by the standards and objectives (e.g., teaching students nominalization, or establishing objectivity) outlined here.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML