-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2023; 13(12): 2029-2031

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20231312.45

Received: Oct. 15, 2023; Accepted: Nov. 12, 2023; Published: Dec. 28, 2023

Clinical Course of Chronic Fascioliasis in a Patient

Laziz N. Tuychiev 1, Mashrabjon K. Shokirov 2, 3, Jakhongir A. Anvarov 1, Shoira B. Mukhidinova 3, Bakhtiyor Soliyev 3

1Tashkent Medical Academy, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

2Fergana Regional Department of Sanitary-Epidemiological Welfare and Public Health Service, Fergana, Uzbekistan

3Fergana Medical Institute of Public Health, Fergana, Uzbekistan

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Fascioliasis is infection with the liver fluke Fasciola hepatica, which is acquired by eating contaminated watercress or other water plants. Clinical manifestations include abdominal pain and hepatomegaly. Diagnosis is by detection of eggs of parasite in stool, duodenal aspirates, or bile specimens. Treatment is with triclabendazole or possibly nitazoxanide. Acute fascioliasis infection can cause abdominal pain, hepatomegaly, nausea, vomiting, intermittent fever, urticaria, malaise, and weight loss due to liver damage. Chronic infection may be asymptomatic or lead to intermittent abdominal pain, cholelithiasis, cholangitis, obstructive jaundice, or pancreatitis.

Keywords: Foodborne trematodes, Human fascioliasis, Fasciola hepatica, Liver damage, Eosinophilia, Cholangitis

Cite this paper: Laziz N. Tuychiev , Mashrabjon K. Shokirov , Jakhongir A. Anvarov , Shoira B. Mukhidinova , Bakhtiyor Soliyev , Clinical Course of Chronic Fascioliasis in a Patient, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 13 No. 12, 2023, pp. 2029-2031. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20231312.45.

1. Introduction

- Fascioliasis is a zoonotic disease caused by the foodborne trematodes Fasciola hepatica and Fasciola gigantica. Fasciola hepatica are found all over the world since their snail vectors are present everywhere, but Fasciola gigantica is limited to Africa and Asia [1]. Significant economic losses and expenditures are caused by fascioliasis infestation in cattle, including impaired fertility, decreased meat, milk, and wool production, cost of anthelmintic medications, reduced weight gain, and loss from death. Around 17 million individuals are infected with Fasciola globally [2,3]. And those parasites have become a new public health problem in countries such as Southeast Asia and Latin America [4,5]. These parasites play a significant role in the occurrence of various manifestations and severity of pathological reactions in various organs and systems of the macroorganism, even in cases of subclinical course of the disease [5,6,7,8].Human fascioliasis mainly occurs in areas where agriculture and animal husbandry are widespread, as well as in areas where rivers, canals and streams flow, which are widely used in agriculture and for household use. However, due to the lack of awareness of medical personnel about this disease, patients are treated in different hospitals for a long time with various misdiagnoses. And when the condition worsens, there is a need for surgical intervention [9,10,11].The main goal for Fasciola hepatica becomes to securely gain a foothold and stay on the walls of the ducts of the biliary tract of the host's liver. The life span of sexually mature Fasciola hepatica in the human body is up to 5 years or more. The incubation period is from 1 to 8 weeks [10,11,12]. The main pathological changes in the human body are usually associated with the migration of the parasite through the liver parenchyma, which lasts up to 6 weeks or more. At the same time, in the migratory phase, due to the development of sensitization of the body with larval antigens, as well as tissue damage along the way, corresponding to the early stage of the disease, it is characterized by severe toxic-allergic reactions, signs of fever, leukocytosis with eosinophilia. After the completion of the migration stage, the sexually mature parasite, having reached the bile duct, can lead to the development of proliferative cholangitis [12].Confirmation of the diagnosis is possible by microscopic examination of feces or duodenal contents with the detection of parasite eggs in them, which are detected no earlier than 3 months after infection [13].For deworming is usually prescribed to the patient after the symptoms of inflammation subside. Before deworming, pathogenetic and symptomatic therapy, enzyme preparations, choleretic and antihistamines, drugs that affect intestinal motility, probiotics, and, if necessary, detoxification therapy are prescribed. The drug of choice for deworming according to the WHO recommendation is triclabendazole, the effectiveness of which is assessed by the disappearance of fasciola eggs in the duodenal contents after 4-6 months [14,15].Early diagnosis of fascioliasis will allow timely therapy and recovery without surgical intervention. With a high-intensity invasion by fasciola or the addition of a secondary bacterial infection, due to the pathogenetic development of immunodeficiency conditions, the prognosis for the patient can be serious, up to death [10]. We present in this article a clinical case demonstrating the difficulty of diagnosing chronic fascioliasis in a patient who used snail therapy.

2. Clinic Case Presentation

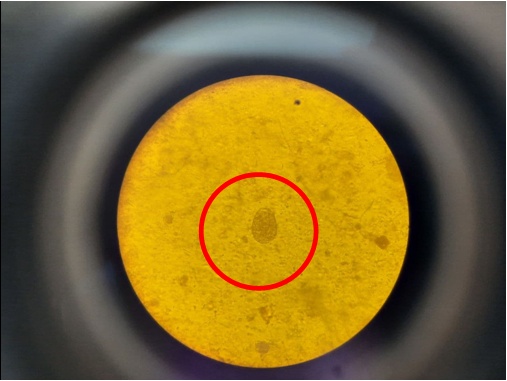

- The patient was born in 1984, lives in the city of Fergana. Works in a beauty salon, deals with snail therapy. According to the patient, she has been ill for 4 years. For the first time in August 2016, an attack developed with localization of pain in the right hypochondrium, in the chest, abdomen and lumbar region, the appearance of rashes on the skin of the face and body.An epidemiological examination revealed the following: the patient was in contact with relatives (close family members) who did not have any signs of the disease. The patient lives in a multi-apartment building in the Fergana city. Uses centralized water as drinking water. She buys food (vegetables, fruits and herbs) mainly at the market. The patient has not left the city for the last 6 months; no guests have come from abroad. The patient does not associate the disease with anything. In the Fergana city the patient went to a city hospital to the gastroenterological department, where after instrumental and laboratory investigations, the patient was diagnosed with acute cholecystitis, for which she received outpatient treatment. However, there were no significant changes in the general condition of the patient, occasionally pains occurred. During the attack, she took analgesics. On December 14, 2019, the patient, due to the appearance of pronounced attack of stabbing pain in the right hypochondrium, shoulder, back, and chest, as well as in the abdomen, called an ambulance, which took the patient to the Fergana General Hospital. Based on the above complaints, a sharp decrease in working capacity, general malaise, nausea, vomiting, the presence of icterus of the sclera and skin, loss of appetite, the appearance of darkening of the color of urine (choluria) and acholic feces, she was hospitalized in the department of abdominal surgery with a diagnosis of choledocholithiasi, mechanic jaundice, and biliary hypertension. An objective examination of the general condition of the patient is severe, in clear mind. The musculoskeletal system is without deformation. Sclera and skin are icteric (++). Tissue turgor is preserved. Peripheral lymph nodes and peritoneal lymph nodes are not enlarged. Vesicular breathing is auscultated in both lungs. Heart sounds are rhythmic, clear, pulse is 102 beats per minute, medium filling and tension. Arterial pressure is 120/70. Tongue wet, white coating. The abdomen is soft on palpation, sensitive in the right hypochondrium and in the epigastric region. Ortner’s and Murphy’s symptoms are positive. Shchetkin-Blumberg’s symptom is negative. The liver and spleen are not enlarged. Intestinal peristalsis is preserved, the stool is acholic, the color of urine is dark. Meningeal symptoms are all negative. On December 16, 2019, the patient underwent an examination of the analysis of feces and bile (duodenal content) in the parasitological laboratory of the Center for Sanitary and Epidemiological Welfare and Public Health of Fergana Region. In the analysis of feces, parasites and helminths were not found. Fasciola hepatica eggs were found in the duodenal aspirate (Fig. 1).

| Figure 1. Fasciola hepatica egg in duodenal aspirate |

| Figure 2a. Fasciola hepatica which removed during ERPCG |

| Figure 2b. Fasciola hepatica which removed during ERPCG |

3. Conclusions

- 1. The presented clinical case demonstrates the difficulties that doctors have to face in the diagnosis and treatment of fascioliasis. Late treatment of the patient for medical help and untimely diagnosis of the disease can lead to a severe course of the disease;2. The clinical case shows that it is rather difficult to suspect this invasion only on the basis of clinical data, because a similar clinical picture can also be characteristic of other diseases of an infectious and non-infectious nature. It becomes expedient to conduct a study of the patient’s feces, using a standard and publicly available technique for the presence of helminth eggs, which will allow timely elimination of this invasion;3. Epidemiological alertness, careful history taking, and competent analysis of clinical and laboratory data are help to put an early diagnosis and choose the right therapy of this diseases.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML