-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2023; 13(12): 1997-2001

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20231312.38

Received: Nov. 24, 2023; Accepted: Dec. 17, 2023; Published: Dec. 23, 2023

Obliteration and Stricture of the Urethra in Children: Improvement of Surgical Treatment Results

Kh. A. Akilov, Sh. A. Nizomov, B. S. Shukurov

Center for the Development of Professional Qualifications of Medical Workers, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The aim of the study was to improve the treatment results of post-traumatic strictures and urethral obliterations in children using a two-diameter drainage catheter. Introduction. Prostate and bladder neck injuries are more common in childhood. The difficulty of treating urethral injuries is due to lifelong urinary complications (re-formation of strictures, urinary incontinence and erectile dysfunction). In spite of the successes achieved in surgical removal of strictures and obliterations, the percentage of unsuccessful outcomes is still very high and they range from 25 to 50%. Material and methods. The clinical material is based on a retrospective analysis of the treatment of 100 boys aged 3 to 15 years who were treated at the clinic of the Center for the Development of Professional Qualifications of Medical Workers from 2005 to 2021. If the urinary tract infection was “controllable,” surgical treatment was performed (modified Marion-Holtsov surgery with the installation of a two-diameter catheter). Results. According to urethrograms, the length of strictures and obliterations averaged 1.9 ± 0.2 cm. The performed local manipulations and the technique of the surgery caused a smooth course of the early postoperative period. Neither general nor local complications were observed. The wounds healed initially, which allowed the removal of a special drainage catheter from the urethra no later than 8-9 days. Discussion. Common causes of unsuccessful outcomes of the posterior urethra strictures and obliterations of traumatic origin surgical treatment are incomplete removal of scar tissue, unsuccessful suturing of the anastomosis, strong tension on the anastomosis line in the immediate postoperative period, as well as ineffective drainage of the bladder, catheter-associated urinary tract infection. Conclusions. The correct implementation of providing the first aid algorithms for urethral injuries, careful preparation and correct execution of the urethral anastomosis surgical manipulation stages using a two-diameter drainage catheter, with the correct selection of antimicrobial agents for parenteral and topical use allowed to achieve good results in 98.0% of cases, including cases of repeated correction at recurrent strictures and obliterations of urethra.

Keywords: Obliteration, Stricture, Urethra, Marion-Holtsov surgery

Cite this paper: Kh. A. Akilov, Sh. A. Nizomov, B. S. Shukurov, Obliteration and Stricture of the Urethra in Children: Improvement of Surgical Treatment Results, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 13 No. 12, 2023, pp. 1997-2001. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20231312.38.

1. Introduction

- Prostate and bladder neck injuries are more common in childhood. Injuries of the posterior urethra occur in 4-19% due to pelvic fractures because of a vehicle injury. Injuries of the anterior urethra occur due to trauma to the penis or penetrating wound. The difficulty of treating urethral injuries is due to lifelong urinary complications (re-formation of strictures, urinary incontinence and erectile dysfunction) [1,2].A comparative analysis of Clinical Recommendations on urogenital System Injury by the European Association of Urologists (EAU), the American Association of Urologists (AUA) and the Société Internationale d'urologie (SIU) showed that multicenter studies are still relevant today. It is necessary to optimize, improve the quality and increase the degree of evidence of these documents both for the diagnosis and treatment of urethral injuries [3]. In spite of the successes achieved in surgical removal of strictures and obliterations, the percentage of unsuccessful outcomes is still very high and they range from 25 to 50% [4-10]. Moreover, the range of unsuccessful outcomes causes is very diverse, ranging from violations in primary care and diagnosis, ending by imperfections and sins of surgical technique and postoperative management [11-13]. In this regard, the issue of preventing the formation of post-traumatic strictures and their recurrence remains a particularly urgent problem of pediatric surgery.The aim of the study was to improve the treatment results of post-traumatic strictures and urethral obliterations in children using a two-diameter drainage catheter.

2. Material and Methods

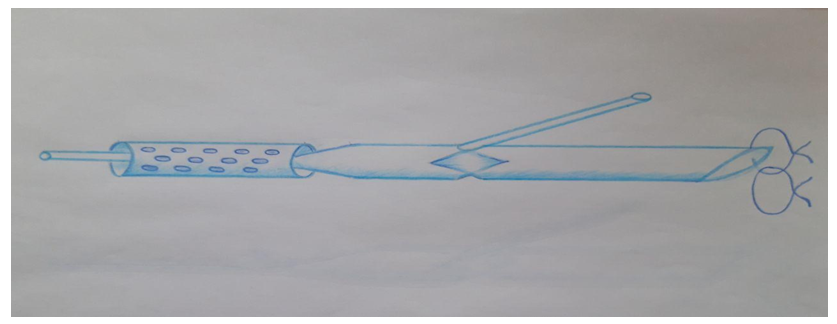

- The clinical material is based on a retrospective analysis of the treatment of 100 boys aged 3 to 15 years who were treated at the clinic of the Center for the Development of Professional Qualifications of Medical Workers from 2005 to 2021. The age of the patients varied as follows: from 3 to 7 years (n=10), from 7 to 12 years (n=56), and from 12 to 15 years (n=34). 34 (34%) of them had strictures and 66 (66%) had obliterations. By localization: in the membranous part (n=23 (46%)), in the prostatic (n=24 (24%) or in both parts of the urethra (n=28 (28%)). One (2%) patient had a complete separation of the urethra from the neck of the bladder followed by the development of the posterior urethra stricture. In 72 (72%) cases, pelvic bone injuries were the cause of damage, in 28 (28%) children - a fall from a height. Previously, 62 (62%) patients were operated in clinics at the place of dislocation: strictures and obliterations were recurrent when they admitted to our hospital. 34 of them were operated according to the Marion-Holtsov method, 28 patients - according to Cross-Fronstein technique. After these surgeries, 34 patients were performed prolonged unsuccessful urethral bougienage. The remaining 38 (38%) patients were not operated on before being admitted to our hospital. All patients were performed ascending and descending urethrography, ultrasound of the urethra and bladder, urethroscopy, and possibly mictional cystourethrography. If necessary, the neck of the bladder, the inner opening of the urethra and the urethra sections proximal to the affected area were examined through a cystostomy fistula. Control uroflowmetry was performed after surgery when catheters and drains were removed. Erectile function was also evaluated by the presence of a morning spontaneous erection of the penis in the boy.All 100 patients already had suprapubic cystostomy drainage upon admission. After taking urine for bacteriological examination, drainage replacement and sanitation of the urinary tract were performed. When urinary tract infection was "controllable", a modified Marion-Holtsov surgery with the installation of a two-diameter catheter was performed (patent IDP No. 05277, 19.11.2001 (Fig. 1)).

| Figure 1. Two-diameter catheter for urethra and bladder drainage |

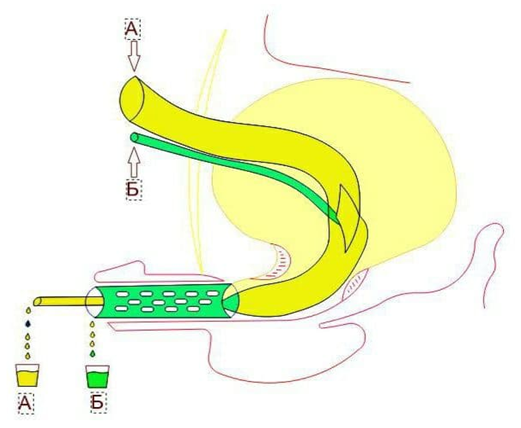

| Figure 2. Catheter functioning scheme |

3. Results

- According to urethrograms, the length of strictures and obliterations averaged 1.9 ± 0.2 cm. Intraoperatively, altered areas of the urethra were released with great care. The scar-altered part of the urethra was cut off as close as possible to the pathological areas. After excision, the diastasis between the proximal and distal parts averaged 3.8 ± 0.2 cm. That is why, maximum mobilization of the distal part of the urethra was performed to reduce the tension of the anastomosis line. In one case, mobilization of the bladder neck was performed in a patient with separation of the urethra from the bladder neck. The next step was to install a two-diameter polyvinyl chloride catheter, the dimensions of which were selected individually for each case. Then an anastomosis was performed - monofilament sutures were placed evenly around the circumference, as it was mentioned above.Early postoperative treatment did not differ from generally accepted principles. But at the same time, we especially focused on three factors. The first factor was the selection of a parenteral antibiotic, when the basis was not only the result of a bacteriological study, but also the features of the microbial landscape of the entire cohort of patients. Nosocomial flora prevailed in our patients, when a protected antibiotic with bactericidal abilities in relation to nosocomial strains with a sufficient evidence base should be chosen.The second factor was our proposed constant irrigation of the bladder with sterile solutions containing an antiseptic component. Chlorhexidine bigluconate or dioxidine was used for this purpose.The third factor was regular irrigation of the urethral anastomosis site, followed by the introduction of antibiotics through the microcatheter we have proposed. By other words, we carried out systematic local rehabilitation of the wound and local treatment of infection.For parenteral administration, cephalosporin antibiotics of the third generation were chosen, in particular, Ceftriaxone and Ceftriaxone Sulbaktam. At insufficient efficiency of antibacterial therapy (increased body temperature and uncontrolled infection according to staged urine analysis), they were replaced to Cefoperazone sulbactam. Aminoglycosides – gentamicin - were used for topical application. In cases of Candida presence, 50 mg/day fluconazole was included.Irrigation of the bladder was carried out using a sterile saline solution (0.9% sodium chloride solution) with an antiseptic. Chlorhexidine bigluconate (in all age groups) or Dioxidine (only in the older age group) was used as an antiseptic component. Irrigation of the anastomosis zone was carried out with 0.5% dioxidine solution ( hydroxymethyl quinoxalindioxide) through a catheter drainage tube from 10 to 50 ml, depending on the transparency and purity of the washing waters 2 times a day. The treatment course was 7-9 days, daily, until the catheter was removed.Thanks to the use of a special draining catheter, local complications of infectious genesis were not observed in any case, which allowed to prevent relapse, as other surgeons noted. A recurrence of stricture was observed only in two cases. It was a repeated surgery, when during the intervention a large extent of diastasis was detected between the healthy ends of the urethra. It turned out to be more than 6 cm, and this patient, for technical reasons, had to be used to restore the urethra with a flap of scrotum skin on the vascular pedicle.The performed local manipulations and the technique of the surgery caused a smooth course of the early postoperative period. Neither general nor local complications were observed. The wounds healed initially, which allowed the removal of a special drainage catheter from the urethra no later than 8-9 days. After the surgery, the maximum volume of the bladder, the thickness of its wall, the volume of residual urine and the time of urination were monitored. The results of these studies revealed no deviations from the age criteria of the norm. Also, no significant differences with the data from long-term examinations were observed. 98 children had no complaints, the urine stream was normal, the data of the simplified uro-flowmetric index (Goldberg B.B., 1974) were within normal limits (14.3 + 3.3 ml/s after removal of the catheter on the 10th day after surgery; 23.6+4.9 ml/s 3-6 months after surgery; 24.9+5.8 ml/s 12 months after surgery, P > 0.05). Taking into account all objective data, recurrence of stricture at the site of anastomosis was excluded. The results of the surgery in the long-term period after 3-6 months (n=44) and 1 year (n=36) were checked by interview, direct checkup and examination.

4. Discussion

- The problem of treating urethral strictures in children is a very difficult task. Today, there are various methods of treatment, ranging from endoscopic procedures, ending with open surgical interventions. Urethral strictures in children have a huge impact on the future life of children if they are not treated properly. The problem has not only a material side, but also an equally important psychological aspect, both for the child and the whole family. Therefore, the main goal of the surgeon is to find a minimally invasive procedure with a short cure time. V.N. Tkachuk, B.K. Komyakov (1990) in their works, noted relapses in 56% of operated patients due to posttraumatic strictures of the urethra. During the Marion-Holtsov surgery in the posterior urethra, 3 patients out of 7 cases had a relapse (Kudryavtsev L.A., 1993). A.Ahmed, G.S.Kalay (1997) noted a relapse in 20.9% of cases after end-to-end anastomosis of the urethra, which were then re-operated.We prepared a questionnaire For a retrospective analysis of the causes of unsuccessful treatment of 62 patients with recurrent strictures. Possible reasons were divided into groups: technical, local and general. Intraoperative errors were attributed to technical reasons: incomplete removal of scarred tissues (55%), unsuccessful suturing of the anastomosis (46%), poor-quality suture material (34%), strong tension of the anastomosis line (33%) and ineffective drainage of the bladder (65%). Local causes included stagnation in the area of anastomosis, local urinary infection. The general ones included the lack of a systematic approach at the prehospital stage, when iatrogenic injury or aggravation of damage was often observed as a result of multiple and sometimes violent attempts to catheterize the urethra at the initial stages of emergency care (45% of cases). This is the result of non-compliance with the standards of emergency care, where retrograde urethrography is the primary diagnostic procedure of choice for a specific assessment of possible injury of the urethra and determining the subsequent actions of specialists [14]. Another factor leading to the inefficiency of urethral strictures surgical treatment should be considered the occurrence of spontaneous erections in the early postoperative period (53%). In our observations, the most frequent pathogens of infectious and inflammatory diseases of the urinary system were microorganisms of the Enterobacteriaceae and Proteus families, less often St. saprophiticus. A similar spectrum of microorganisms in the microbiological examination of urine was obtained by most authors [15, 16, 17]. Proper selection of antimicrobial therapy components in the preoperative and postoperative period, achievement of controllability of urinary tract infection, effective drainage in the early postoperative period and washing of the anastomosis zone prevents its infection and has a beneficial effect on the healing processes and is the main feature of relapse prevention.The next main task is adequate drainage and irrigation of the bladder cavity, and most importantly, the anastomosis zone and the lumen between the drainage and the urethral wall. Our offered catheter solves these problems. 98.0% from 100 operated children had good results due to the use of a two-decameter drainage catheter. Only two patients had a relapse, which was re-operated with good long-term results. There were no other significant complications associated with the underlying disease.

5. Conclusions

- Careful preoperative preparation, gentle and economical resection within healthy tissues of well-mobilized anastomosed ends of the urethra and the use of a two-diameter drainage catheter allowed us to reduce the degree of tension of the anastomosis line both intraoperatively and in the early postoperative period (by preventing spontaneous erections).Prevention of local complications of urinary tract infection can prevent relapses of elimination of the posterior urethra strictures and obliterations of traumatic origin in children. The correct implementation of providing the first aid algorithms for urethral injuries, careful prepara-tion and correct execution of the urethral anastomosis surgical manipulation stages using a two-diameter drainage catheter, with the correct selection of antimicrobial agents for parenteral and topi-cal use allowed to achieve good results in 98.0% of cases, including cases of repeated correction at recurrent strictures and obliterations of urethra. The authors declare no conflict of interest. This study does not include the involvement of any budgetary, grant or other funds. The article is published for the first time and is part of a scientific work.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML