Mamatkhujaeva Gulnarahan Najmidinovna

Department of Ophthalmology, Andijan State Medical Institute, Andijan, Uzbekistan

Correspondence to: Mamatkhujaeva Gulnarahan Najmidinovna, Department of Ophthalmology, Andijan State Medical Institute, Andijan, Uzbekistan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Abstract

Refractive errors remain one of the most topical issues in pediatric ophthalmology. Currently, there is an increase in their prevalence among children and adolescents. This article provides information on the incidence of refractive errors in children and adolescents with tuberculosis.Studies have shown that the most common refractive error in children and adolescents with tuberculosis is myopia - in 17.3±0.9% of cases. Astigmatism was detected in 8.0±0.6% of cases, moderate hypermetropia in 6.9±0.6%, and high hypermetropia in 3.5±0.4% of the total number of patients examined.

Keywords:

Refractive errors, Incidence, Children, Adolescents, Tuberculosis, Myopia, Hypermetropia, Astigmatism

Cite this paper: Mamatkhujaeva Gulnarahan Najmidinovna, Incidence of Refractive Errors in Children and Adolescents with Tuberculosis, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 13 No. 12, 2023, pp. 1908-1911. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20231312.19.

1. Introduction

Refractive errors are one of the most common pathologies of the organ of vision and are the main cause of visual impairment in children and adolescents [1,2,5].The relevance of the study of refractive errors, due to the increase in their prevalence among children and adolescents, is growing [6,7,12].One of the main reasons for the development of low vision in children and adolescents is myopia. In young children, the incidence of myopia is 6-8%, and in older children it increases to 25-30% [8,9].Hypermetropia rarely leads to low vision, but it is what underlies the development of concomitant strabismus and amblypoia in children and adolescents [10,11].Astigmatism is also a common refractive error. According to various authors, astigmatism of 0.5 diopters or more in different countries occurs in 9.8 – 27.2% of children [3,4].Purpose of the study: To study the incidence of refractive errors in children and adolescents with tuberculosis.

2. Materials and Methods of Research

A survey was conducted of children and adolescents with tuberculosis aged from 1 year to 17 years who were being treated for tuberculosis at the Andijan regional anti-tuberculosis dispensary.A comprehensive ophthalmological examination included: determination of visual acuity without and with correction, skiascopy, autorefractometry, biomicroscopy, study of binocular functions, direct and reverse ophthalmoscopy.Clinical, biochemical, immunological, microbiological studies and examination by specialists were also carried out.

3. Results and Discussion

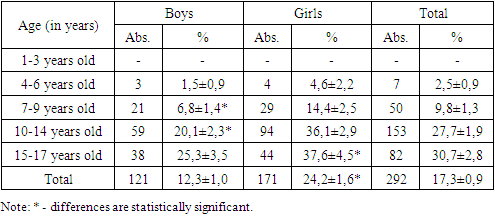

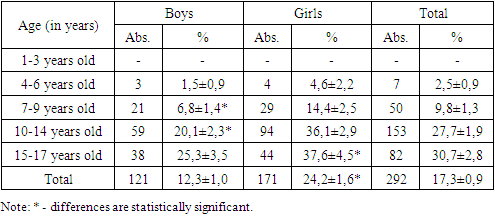

Out of 1690 examined children and adolescents with tuberculosis (985 boys and 705 girls) aged from 1 to 17 years, refractive errors were diagnosed in 603 (35.7%).According to our research, myopia was detected in 292 children and adolescents with tuberculosis, which amounted to 17.3±0.9% of the total number of those examined. Boys accounted for 41.4% (121 people) and girls accounted for 58.6% (171 people) of cases.Таble 1. Analysis of myopia incidence by age reveals the unevenness of its occurrence in individual age groups

|

| |

|

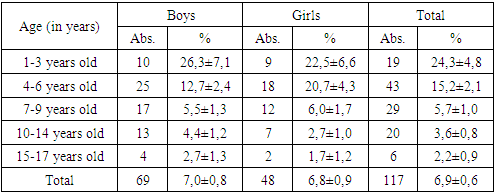

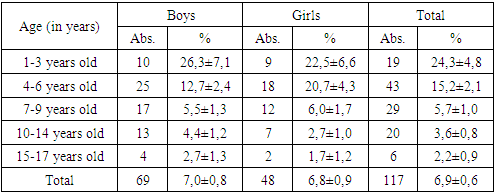

Myopia was not observed in the age group from 1 to 3 years. In the age group of 7-9 years, the frequency of myopia increases, especially among girls from 4.6±2.2 to 14.4±2.5% (P<0.01). In the age groups of 10-14 years and 15-17 years, the frequency of myopia was 36.1±2.9% and 37.6±4.5%, respectively, and these figures were statistically significantly higher than the age group of 7-9 years (p<0.001).Among boys in the age groups of 10-14 years and 15-17 years, the highest detection rate was noted (20.1±2.3% and 25.3±3.5%, respectively). When comparing the frequency of detection of myopia in boys and girls without taking into account age, there is also a statistically significant predominance in girls (24.2±1.6%) compared to boys (12.3±1.0%; P<0.001).Our studies showed that moderate hypermetropia was detected in 117 children and adolescents with tuberculosis, which is 6.9±0.6% of the total number of those examined. In boys it occurred in 69 cases (7.0±0.8%), and in girls - in 48 cases or 6.8±0.9%. The frequency of detection of moderate and high hypermetropia among children and adolescents with tuberculosis is presented in Table 2.Table 2. Detection rate of moderate hypermetropia among children and adolescents with tuberculosis

|

| |

|

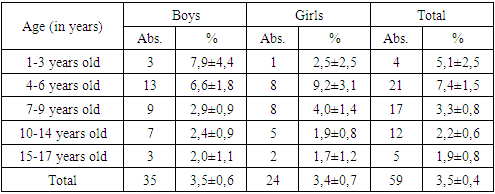

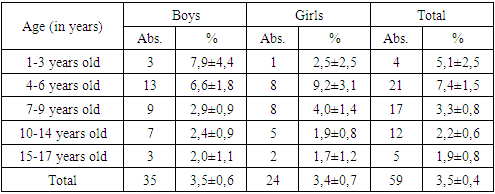

As can be seen from Table 2, moderate hypermetropia was most revealed in the age group from 1 year to 3 years and amounted to 26.3±7.1% in boys and 22.5±6.6% in girls.In the age group from 4 years to 6 years, the incidence of moderate hypermetropia among girls (20.7±4.3%) was 1.6 times higher than among boys (12.7±2.4%).In the age group of 7-9 years, the incidence of moderate hypermetropia was almost the same in boys (5.5±1.3%) and girls (6.0±1.7%).In the age group of 10-14 years, the frequency of moderate hypermetropia was 1.5 times higher in boys (4.4±1.2%) than in girls (2.7±1.0%).In the older adolescent group of 15-17 years old, the incidence of hypermetropia in boys was 1% higher than in girls - 1.7±1.2%, and amounted to 2.7±1.3%. In all age groups, the differences in indicators were statistically insignificant (p>0.05).With hypermetropia of 3.0 diopters and above, all children presented asthenopic complaints. Children complained of a feeling of sand in their eyes, fatigue, pain in the eyes and frontal part of the head.High degree hypermetropia, as can be seen from Table 3, was revealed in 59 children: 35 (59.3%) boys and 24 (40.7%) girls.Table 3. Detection rate of high degree hypermetropia among children and adolescents with tuberculosis

|

| |

|

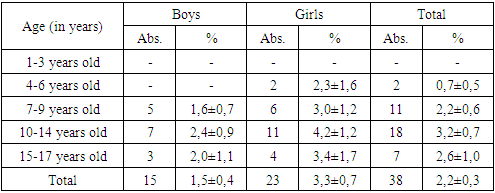

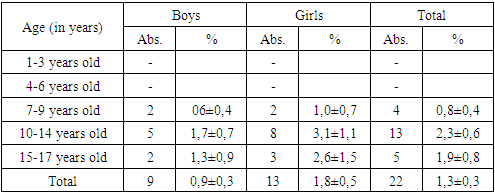

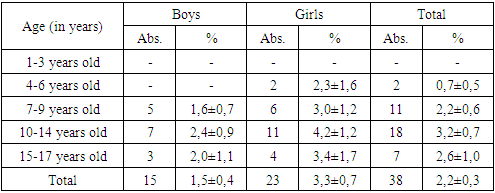

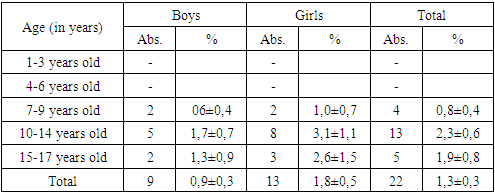

The analysis of detection rate of high degree hypermetropia depending on age and gender showed that in the age group of 1-3 years, the rates for boys were 3.2 times higher than for girls, and amounted to 7.9±4.4% versus 2.5±2.5%. However, these differences were not statistically significant (p>0.05).In the age group of 4-6 years, the ratio of indicators changes: in girls it is higher (9.2±3.1) than in boys (6.6±1.8), by 1.4 times, but statistically the differences are also not significant (p>0.05).In other age groups, no statistically significant differences were found, which indicates that there is no influence of age and gender on the detection rates of high-grade hypermetropia in children and adolescents with tuberculosis.Astigmatism is known to be a congenital condition. In some children and adolescents it may be minor, is physiological and does not interfere with normal vision.In some children and adolescents, astigmatism can be higher than physiological values and significantly reduces distance and near visual acuity.During the examination, we identified astigmatism in 135 children and adolescents with tuberculosis, which is 8.0±0.6% of the total number of those examined. There were 44.4% (60 people) boys, and 55.6% (75 people) girls.In the examined children and adolescents with tuberculosis, all types of astigmatism were detected, namely: simple myopic astigmatism was detected in 38 (2.2±0.3%), complex myopic – in 22 (1.3±0.3%), simple hyperopic – in 25 (1.5±0.3%), complex hyperopic – in 17 (1.0±0.2%), mixed astigmatism was detected in 33 (1.9±0.3%).The detection rate of simple myopic astigmatism depending on the age and gender of the examined is presented in Table 4.As can be seen from Table 4, the detection of simple myopic astigmatism increases from 6 to 14 years; at the age of 15-17 years, this figure decreases slightly. Among girls, simple myopic astigmatism was detected almost 1.5 times more often than in boys - 3.3±0.7% versus 1.5±0.4%, respectively (P<0.01).Table 4. Incidence of simple myopic astigmatism among children and adolescents with tuberculosis

|

| |

|

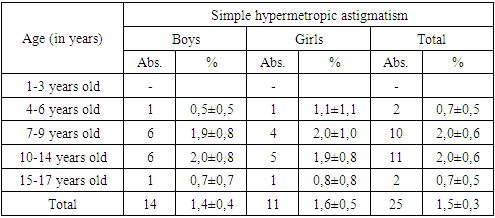

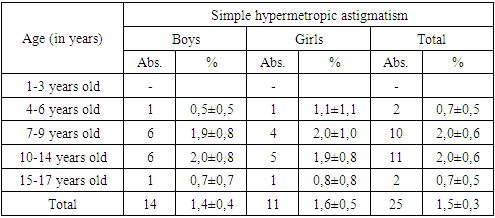

The trends in the incidence of complex myopic astigmatism in the surveyed population (Table 5) are similar to simple ones and girls also predominate over boys by 2 times: 1.8±0.5 versus 0.9±0.3, however, the differences are not statistically significant (P> 0.05).Table 5. Incidence of complex myopic astigmatism among children and adolescents with tuberculosis

|

| |

|

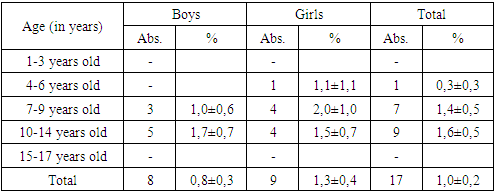

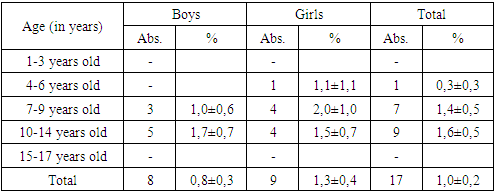

The incidence of simple hypermetropic astigmatism in girls and boys was almost the same, both depending on age and gender and amounted to 1.4±0.4% and 1.6±0.5%, respectively (Table 6).Table 6. Incidence of simple hypermetropic astigmatism among children and adolescents with tuberculosis

|

| |

|

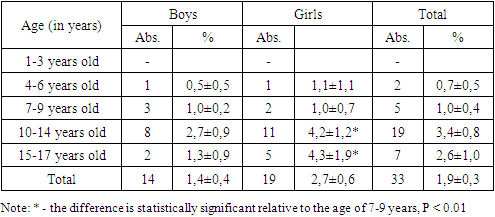

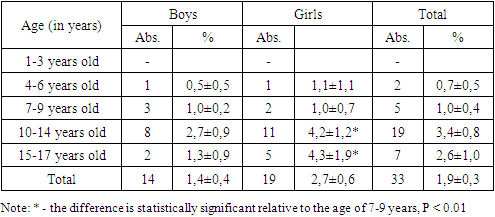

Complex hypermetropic astigmatism among boys was revealed in 0.8±0.3% of cases, among girls in 1.3±0.4% of cases, the differences are not statistically significant (Table 7). The patterns and trends in the detection of complex hypermetropic astigmatism are similar to the characteristics of other types; it should be noted that not a single case of this type of astigmatism was identified in the age group of 15-17 years.Table 7. Incidence of complex hypermetropic astigmatism among children and adolescents with tuberculosis

|

| |

|

The analysis of incidence of mixed astigmatism allows us to conclude that detection rates, depending on age and gender, coincide in level and dynamics with other types of astigmatism in the studied groups (Table 8). Noteworthy is the fact that girls in all age groups have higher rates, and according to the final indicators, 1.9 times more than boys (2.7±0.6% versus 1.4±0.4%).Table 8. Incidence of mixed astigmatism among children and adolescents with tuberculosis

|

| |

|

Decrease in visual acuity in children and adolescents with astigmatism was in all cases accompanied by asthenopic complaints. With visual stress, children noted pain in the eyes, in the forehead and temples, headache, dizziness, irritability, and fatigue. Asthenopic complaints were more often detected in girls.Studies have shown that in children and adolescents with tuberculosis, the highest percentage of detection was simple myopic (2.2±0.3%) and mixed astigmatism (1.9±0.3%).The incidence of astigmatism was statistically significantly higher among girls (10.6 ± 1.1%) than among boys (6.1 ± 0.8%; P < 0.001).

4. Conclusions

Thus, our results showed that the most common refractive error in children and adolescents with tuberculosis is myopia. The incidence of myopia is 17.3±0.9%. Astigmatism was detected in 135 children and adolescents with tuberculosis, which is 8.0±0.6% of the total number of those examined.The incidence of moderate hypermetropia among children and adolescents with tuberculosis was 6.9±0.6%, and high degree hypermetropia – 3.5±0.4%.Refractive errors are the main cause of visual impairment in children and adolescents with tuberculosis and require timely diagnosis and correction to prevent an irreversible decrease in visual acuity.

References

| [1] | Alemayehu A.M., Belete G.T., Adimassu N.F. Knowledge, attitude, and associated factors among primary school teachers regarding refractive error in school children in Gondar city, Northwest Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2018; 13(2): 31–40. - PMC - PubMed. |

| [2] | Aldasheva N. A., Iskakbaeva D. S., Bakhytbek R. B. et al. The structure of refractive errors in schoolchildren. // Point of view. East - West. - 2019. - No. 3. - pp. 24-26. |

| [3] | Botabekova T.K., Aldasheva N.A., Abdullina V.R. and others. Development of a comprehensive program for the prevention and treatment of refractive errors in school-age children. // RMJ. Clinical ophthalmology. 2021. -No. 3. - P. 135-142. |

| [4] | Development of Corneal Astigmatism (CA) according to Axial Length/Corneal Radius (AL/CR) Ratio in a One-Year Follow-Up of Children in Beijing, China / F.Wang, L. Xiao, X. Meng, L. Wang, D. Wang // J. Ophthalmol. – 2018: 4209236; URL: https://www.hindawi.com/journals/joph/2018/4209236/ DOI: 10.1155/2018/4209236. eCollection 2018. |

| [5] | Global and regional estimates of prevalence of refractive errors: Systematic review and meta-analysis /H. Hashemi, A. Fotouhi, A. Yekta, R. Pakzad, H. Ostadimoghaddam, M. Khabazkhoobe // Journal of Current Ophthalmology. - 2018 - Vol. 30, № 1.- P. 3–22. DOI: 10.1016/j.joco.2017.08.009. |

| [6] | Gordeeva S.A., Rykun V.S., Kurenkov E.L. Some clinical and anatomical features of refractive errors in children. // Bulletin of the Council of Young Scientists and Specialists of the Chelyabinsk Region. -2017.-No. 4. pp. 5-8. |

| [7] | Guillon-Rolf R, Grammatico-Guillon L, Leveziel N, Pelen F, Durbant E, Chammas J, Khanna RK. Refractive errors in a large dataset of French children: the ANJO study. Sci Rep. 2022 Mar 8; 12(1): 4069. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-08149-5.5. |

| [8] | Kurganova O.V., Markova E.Yu., Bezmelnitsyna L.Yu. and others. Myopia and other refractive errors in school-age children. // Practical medicine. 2018. - No. 3. – pp. 106-109. |

| [9] | Lorato MM, Yimer A, Kebede Bizueneh F.Prevalence of myopia in school-age children in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. SAGE Open Med. 2023 Oct 6; 11: 20503121231200105. doi: 10.1177/20503121231200105. |

| [10] | Ramírez-Ortiz MA, Amato-Almanza M, Romero-Bautista I, Klunder-Klunder M, Aguirre-Luna O, Kuzhda I, Resnikoff S, Eckert KA, Lansingh VC. A large-scale analysis of refractive errors in students attending public primary schools in Mexico. Sci Rep. 2023 Aug 19; 13(1): 13509. doi: 10.1038/s41598-023-40810-5. PMID: 37598286; PMCID: PMC10439951. |

| [11] | Santiago HC, Rullán M, Ortiz K, Rivera A, Nieves M, Piña J, Torres Z, Mercado Y. Prevalence of refractive errors in children of Puerto Rico. Int J Ophthalmol. 2023 Mar 18; 16(3): 434-441. doi:10.18240/ijo.2023.03.15. |

| [12] | Sheeladevi S, Seelam B, Nukella PB, Modi A, Ali R, Keay L. Prevalence of refractive errors in children in India: a systematic review. Clin Exp Optom. 2018 Jul; 101(4): 495-503. doi: 10.1111/cxo.12689. Epub 2018 Apr 22. PMID: 29682791. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML