-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2023; 13(9): 1317-1321

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20231309.31

Received: Aug. 6, 2023; Accepted: Sep. 1, 2023; Published: Sep. 28, 2023

Mortality Predictions in Elderly Patients with Acute Heart Failure in the Intensive Care Unit

Koyirov Akmal Kambarovich

Head of the Department of Therapeutic Resuscitation of the Republican Emergency Medical Research Center

Correspondence to: Koyirov Akmal Kambarovich, Head of the Department of Therapeutic Resuscitation of the Republican Emergency Medical Research Center.

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Introduction. A number of factors of unfavorable outcome in the acute of chronic heart failure (AHF) have been identified according to research data. The role of geriatric syndromes as predictors of mortality in elderly patients with AHF has not been sufficiently studied. Assessment of the syndrome of senile asthenia as a marker of mortality in patients with AHF in the intensive care unit (ICU) is relevant. Objective: to evaluate and identify the most significant predictors of mortality and prolonged ICU stay in patients with AHF. Materials and methods: 107 patients aged 46-95 years with AHF functional class III-IV were included. 4 groups were formed: 1st - 29 people (53.9 ± 4.5 years), middle age (46-60 years); 2nd - 31 people (68.3 ± 5.0 years) elderly (61-74 years); 3rd - 40 people (81.5 ± 4.1 years) old age (75-89 years). 4th - 7 people (92.4 ± 1.4 years) of the age of centenarians (> 90 years). The patients underwent: examination, echocardiography. Geriatric syndromes were assessed using a comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGE) using the Specialized Geriatric Examination program. Results. The longest duration in ICU was in the old age group- 5.13 ± 1.9 days. Mortality in the ICU on the 1st day was 1.07%, over the whole period - 14%. The most significant independent predictors of mortality in ICU (OR [95% CI]) were terminal stage of CHF (52.5 [4.62; 1419.34], p <0.01), severe frailty with terminal (32.0 [5.59; 608.84], p <0.01), IV functional class NYHA (10.6 [2.72; 70.31], p <0.01). The most significant independent predictors of long-term stay in ICU (OR [95% CI]) were terminal stage of CHF (3.6 [2.57; 5.38], p <0.01), terminal frailty (2.9 [1, 85; 4.59], p <0.01), severe frailty (2.6 [1.72; 3.97], p <0.01). Conclusion. Terminal and severe senile asthenia are independent predictors of a 32-fold increase in mortality and an almost 2.9-fold increase in the duration of stay in ICU of elderly and senile patients.

Keywords: Heart failure, Frailty, Elderly, Senile age, Mortality

Cite this paper: Koyirov Akmal Kambarovich, Mortality Predictions in Elderly Patients with Acute Heart Failure in the Intensive Care Unit, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 13 No. 9, 2023, pp. 1317-1321. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20231309.31.

Article Outline

1. Relevance

- Rapid population aging is occurring worldwide. According to WHO data, the proportion of people over 60 years old is projected to increase from 12% to 22% between 2015 and 2050 [24]. The steady growth in the number of elderly individuals is accompanied by an increase in the prevalence of chronic heart failure (CHF) [4], [5], [8], [12]. Approximately 10% of elderly individuals have this condition [15]. In the future, thanks to advances in medicine, the proportion of patients with CHF will continue to grow, leading to significant healthcare costs. Acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF) holds a special place in the structure of CHF, characterized by the progression of heart failure symptoms, requiring emergency hospitalization and intensive therapy [9]. Over the past decade, there has been a significant increase in hospitalizations due to ADHF. According to the European registry EHFS (EuroHeart Failure Survey), 65% of elderly patients are hospitalized for this reason [1], [2], [7]. Each episode of decompensated heart failure (HF) worsens the prognosis of the patient and requires specialized treatment and temporary correction of previous HF therapy [9]. The annual mortality rate after discharge for such patients reaches 30% [1], [9]. Furthermore, while the average survival rate for patients after the first episode of decompensated HF is 2.4 years, it decreases to 1.4 years after the second episode [11]. As the prevalence of decompensated HF increases, there is a growing need to study the risk factors for mortality. A significant number of risk factors for mortality in decompensated HF have been identified. It has been established that clinical parameters such as a decrease in blood pressure (BP) <100 mmHg, a decrease in glomerular filtration rate (GFR) <50 ml/min/1.73 m2, and the presence of anemia are independent predictors of an unfavorable prognosis [2], [7]. One of the geriatric syndromes widely prevalent among the elderly is the syndrome of geriatric asthenia (GA) [6]. The association between GA and HF has been proven by the results of numerous studies [13], [20], [21]. According to the results of a prospective single-center study, GA was verified in 28% of patients with acute heart failure (AHF). The mortality rate in this group of patients within 1 year was 59.09%, which was twice as high as the mortality rate among individuals without asthenia - 29.09% [15]. According to the FRAIL-HF study, the presence of GA in patients with HF was associated with a 2.13-fold increase in mortality during 1 year of observation [23]. The relevance of this study is justified by the focus on verifying predictors of mortality in the intensive care unit (ICU) among elderly patients with decompensated HF.The aim of this study is to evaluate and identify the most significant predictors of mortality and prolonged stay in the ICU among patients with AHF in old and very old age.

2. Materials and Methods

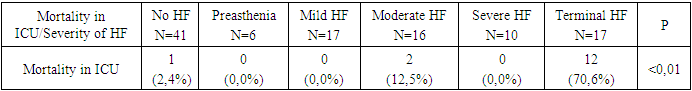

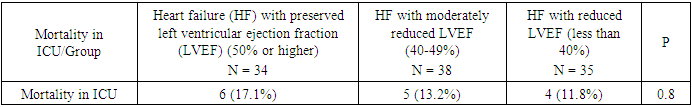

- The study was conducted at the Cardio-Therapeutic Resuscitation Department of the Republican Scientific Center of Emergency Medicine, Tashkent, Uzbekistan. A total of 107 patients aged 46-95 years with NYHA class III-IV heart failure (HF) were analyzed. The patients were divided into four age groups: the first group consisted of 29 individuals of middle age (46-60 years); the second group included 31 elderly patients (61-74 years); the third group comprised 40 elderly patients (75-89 years). The fourth group consisted of 7 long-lived individuals (over 90 years). Due to the small size of the long-lived group (only 7 people), these patients were only represented at the descriptive statistics level and were not included in intergroup comparisons. In the current study, patients were classified into six groups based on the severity of geriatric asthenia (GA): the first group included 41 patients without GA; the second group consisted of 6 patients with pre-asthenia; the third group included 17 patients with mild GA; the fourth group consisted of 16 patients with moderate GA; the fifth group was represented by 10 patients with severe GA; the sixth group included 17 patients with terminal GA. Additionally, all patients were divided into three groups based on the left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF): the first group consisted of 34 patients with preserved LVEF (50% or more); the second group included 38 patients with moderately reduced LVEF (40-49%); the third group was represented by 35 patients with reduced LVEF (less than 40%).HF was verified according to the criteria recommended by the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) [9]. Exclusion criteria from the study included severe liver dysfunction (Child-Pugh class C), chemotherapy in patients with oncopathology, patients on renal replacement therapy with end-stage chronic kidney disease (glomerular filtration rate <15 ml/min), acute myocardial infarction, acute cerebrovascular events, massive pulmonary embolism, acute phase of inflammatory diseases, and any clinical conditions that, in the opinion of the physician, could hinder the patient's participation in the study.A comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) was performed for all patients to verify the GA syndrome, using the specialized geriatric examination software "Gerontolog" [3]. Each section contains more than 10 questions, which are scored. The scores are automatically calculated, and the degree of GA syndrome is determined.All patients underwent echocardiography (EchoCG) using a portable ultrasound device (Philips) to assess the LVEF using the Simpson's method. In the study cohort, the mortality rate within the first 24 hours of ICU stay and throughout the entire period of ICU stay was evaluated.

3. Statistical Data Processing

- The analysis of the obtained data was performed using the statistical computing environment R 4.1.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Differences were considered statistically significant at p <0.05.The selection of predictors (from those mentioned above) for obtaining a multifactor logistic regression model was performed using the inclusion-exclusion method based on AIC (Akaike Information Criterion).

4. Results

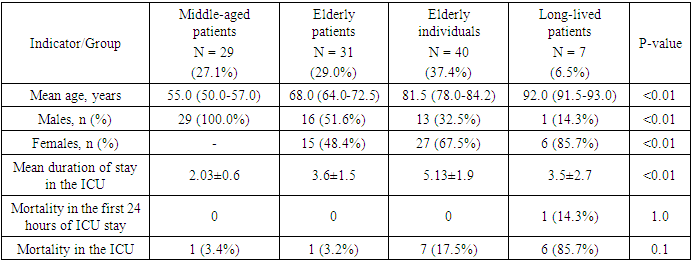

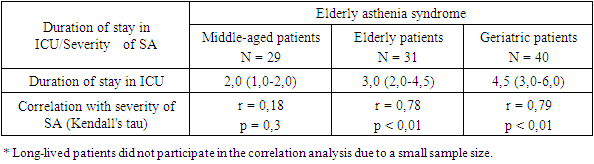

- The study included 107 patients admitted to the ICU with a diagnosis of decompensated heart failure. Depending on age, 4 groups were formed, in which significant gender differences were noted (p <0.01). The first group included middle-aged patients (n = 29), all of whom were male. The second group consisted of elderly patients (n = 31) and included 16 (51.6%) males and 15 (48.4%) females. The third group, consisting of elderly individuals (n = 40), had a predominance of females (67.5%). The long-lived patients (n = 7) formed the fourth group, where there was also a predominance of females (87.5%) (Table 1).During the observation period in the ICU, 15 (14%) patients died. One patient died within the first day of ICU stay. There were no significant differences in mortality within the first day of ICU stay between the groups (p = 1.0). The age groups also did not differ significantly in terms of ICU mortality (p = 0.1). However, higher mortality was observed among the long-lived patients. During the ICU stay, 6 (85.7%) patients older than 90 years died (Table 1).The duration of ICU stay was calculated. With increasing age, there was a significant tendency towards longer ICU stay (p <0.01). The average duration of ICU stay for middle-aged patients was 2.03 ± 0.6 days. For elderly individuals, this indicator was slightly higher - 3.6 ± 1.5 days. The group of elderly individuals showed the longest duration of ICU stay - 5.13 ± 1.9 days. For individuals older than 90 years, the average duration of ICU stay was 3.5 ± 2.7 days (Table 1).

|

|

|

|

|

|

5. Discussion

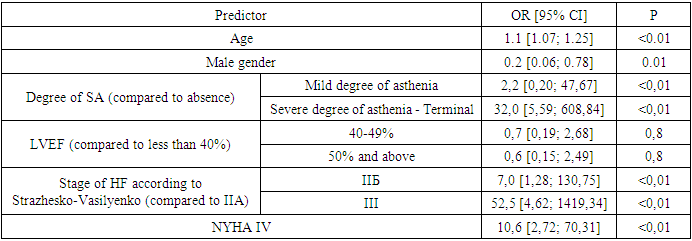

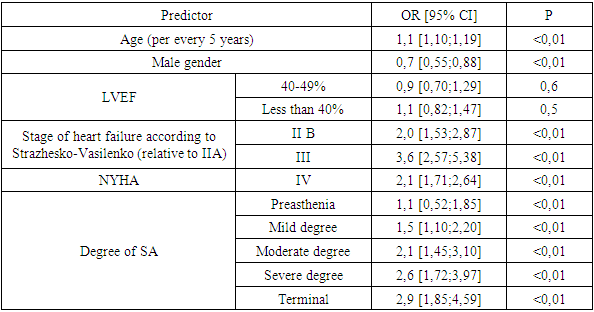

- The present study identified the influence of SA on an increase in fatality in ORIT in patients with decompensated CHF. The highest fatality in ORIT was observed in the group of patients with terminal asthenia (70.6%).Data from other studies also show an increase in fatality when CHF and SA are combined. In the study by Boxer et al., by the fourth year of observation, the relative risk of death in patients with CHF and SA increased by 1.5 times [13]. According to the Health Aging and Body Composition Study (HABC), after 9 years of observation, the risk of death in the group of patients with a combination of CHF and three criteria of elderly asthenia reaches 100%, while with the presence of one criterion, it is 55% [14], [19].Despite the small sample size, the present study is the first to consider SA as a predictor of fatality in ORIT. The presence of terminal/severe SA increased the risk of fatality in patients with decompensated CHF by 32 times. Along with SA, the presence of terminal stage of CHF (III according to Strazhesko-Vasilyenko) and IV FC according to NYHA also had an influence on fatality in ORIT.By the current moment, there are numerous studies dedicated to identifying risk factors for fatality in patients with CHF. According to the OPTIMIZE-HF registry, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) is the strongest independent predictor of in-hospital fatality, but only up to a level of 38%. Beyond 38%, the reliability of this indicator diminishes [17]. S. Pocock et al. conducted an analysis of the CHARM registry and identified 21 independent predictors of fatality in CHF. The most significant prognostic factors were age (patients over 60 years old had a 46% increased fatality rate for every subsequent 10 years), decreased LVEF (patients with LVEF of 45% had a 13% increased fatality rate for every 5% decrease in LVEF), and the presence of diabetes [22]. According to the results obtained by R. Goldberg et al., the strongest influences on the risk of fatal outcomes were patient age and the time period since the first hospitalization [17]. However, the influence of geriatric status of the patient has not received sufficient attention.In the present study, significant differences in the length of stay in ORIT were observed. The group of elderly patients had the longest length of stay in ORIT - 5.13±1.9 days. For elderly patients, the influence of SA on the length of stay in ORIT was identified for the first time. A strong and significant correlation between SA and the duration of observation in ORIT was established for elderly patients (r = 0.78 and r = 0.79, p <0.01).The SA syndrome is also considered for the first time as a predictor of longer stay in ORIT. The presence of terminal and severe SA increased the duration of stay in ORIT by 2.9 and 2.6 times, respectively. Other significant predictors of prolonged stay in ORIT were terminal stage CHF (III according to Strazhesko-Vasilyenko) and NYHA class IV.The identification of SA in patients with CHF is clinically significant. The SA syndrome is likely to be considered as a factor that hinders the stabilization of patients' condition and is associated with a longer stay in ORIT. Prolonged stay in ORIT (more than 72 hours), in turn, leads to new complications such as Post-Intensive Care Syndrome (PICS). Additionally, in a previous study conducted by us, the role of SA as a factor exacerbating and worsening the prognosis in patients with CHF was established [10].

6. Conclusions

- 1. The highest fatality in ORIT was observed in the group of patients with terminal asthenia - 70.6%.2. Three strongest predictors of fatality in ORIT were identified: terminal stage CHF increased fatality in ORIT by 52 times, the presence of severe/terminal SA increased fatality by 32 times, and NYHA class IV was associated with a 10.6-fold increase in fatality in ORIT.3. For elderly patients with decompensated CHF, terminal stage CHF, and the presence of terminal and severe SA are predictors of longer stay in ORIT. The presence of terminal stage CHF increased the duration of stay in ORIT by 3.6 times. Terminal and severe SA increased the period of observation in ORIT by 2.9 and 2.6 times, respectively.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML