-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2023; 13(7): 990-994

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20231307.30

Received: Jun. 29, 2023; Accepted: Jul. 19, 2023; Published: Jul. 26, 2023

Features of the Hysteroscopic Picture of the Endometrium in Postmenopausal Women

Tyan T. V., Alieva D. A.

Republican Specialized Scientific and Practical Medical Center for Obstetrics and Gynecology, Uzbekistan

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The article studied the hysteroscopic picture and immunohistochemistry in postmenopausal patients with uterine bleeding. All patients underwent therapeutic and diagnostic curettage of the uterine cavity with diagnostic hysteroscopy for the purpose of hemostasis.

Keywords: Hysteroscopic, Endometrium, Postmenopausal women, Atypical endometrial hyperplasia

Cite this paper: Tyan T. V., Alieva D. A., Features of the Hysteroscopic Picture of the Endometrium in Postmenopausal Women, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 13 No. 7, 2023, pp. 990-994. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20231307.30.

1. Introduction

- Uterine bleeding is one of the most common reasons for visiting a gynecologist and performing intrauterine interventions [6]. Uterine bleeding is mostly based on hyperplastic processes of the endometrium [8]. As is known, endometrial hyperplasia and uterine bleeding account for 5 to 25% in gynecological pathology, and it is a medical and social problem due to the high incidence of relapses and the possibility of malignancy [1,2,3]. Despite the improvement of treatment methods, in recent years there has been an increase in the incidence of endometrial hyperplastic diseases, which is associated with an increase in the number of women suffering from metabolic disorders, an increase in the number of chronic somatic pathology, a decrease in immunity, as well as an unfavorable environment, and an increase in life expectancy.If at a reproductive age the doctor makes efforts to preserve the uterus in patients even with atypical endometrial hyperplasia, then, as you know, radical treatment is preferable in old age. However, due to the presence of a number of contraindications to surgical treatment, usually available at this age, a properly selected conservative therapy is a treatment option.However, most authors report that the use of hormone therapy is ineffective in about every fifth patient, a partial response was recorded from 8% to 20%, disease progression was recorded up to 3%, relapse was recorded up to 33% of cases [4,5,7,8].Until now the question of the risk of malignant transformation of hyperplastic endometrium remains open. According to studies, the degree of risk of malignancy of various types of endometrial hyperplasia is determined by the morphological state of the endometrium. Thus, the frequency of malignancy of simple endometrial hyperplasia, according to different authors, is only 2-5% [10]. The risk of progression of complex atypical hyperplasia to invasive cancer is 47% [9].It is traditionally believed that the leading role in the development of endometrial hyperplasia belongs to unbalanced estrogen stimulation. However, research data on the possibility of developing endometrial hyperplasia in the absence of hormonal disorders testify in favor of the presence of other mechanisms for the formation of endometrial hyperplasia associated with local dysregulation of cell proliferation [11].The ambiguity of individual pathogenetic mechanisms, the presence of contraindications for hormonal therapy, the recurrent course of the disease, the often negative attitude of patients to hormonal therapy and radical surgical methods of treatment, as well as the organ-preserving direction in modern medicine necessitates an in-depth study of the pathogenesis of uterine bleeding in any age period of a woman's life [10].In turn, the proliferative activity of the endometrium is assigned a leading role in the mechanism of malignant transformation [4]. In this regard, the study of markers of proliferative activity is of certain scientific and practical interest, which will allow predicting possible malignancy, as well as choosing a rational method of treating postmenopausal patients with uterine bleeding (UB).Purpose of the study. To study the hysteroscopic picture and immunohistochemistry in postmenopausal patients with uterine bleeding.

2. Materials and Methods

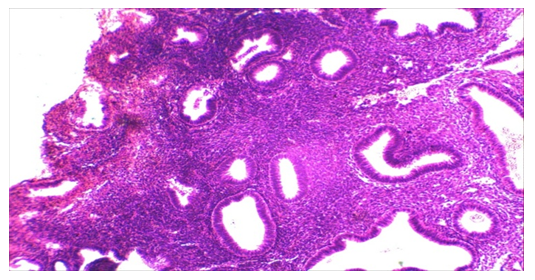

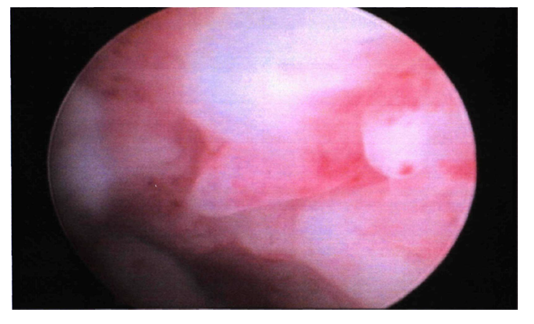

- We studied the clinical and laboratory data of 53 patients admitted to the gynecological department of Republican Specialized Scientific and Practical Medical Center for Obstetrics and Gynecology in the years between 2019 and 2021, with complaints of uterine bleeding in the postmenopausal period of life. The average age of the patients was 66.5±8.2 years, the duration of menopause ranged from 5 to 10 years, on average 7.2±3.3 years.All patients underwent therapeutic and diagnostic curettage of the uterine cavity with diagnostic hysteroscopy for the purpose of hemostasis. Currently the leading method for diagnosing intrauterine pathology is hysteroscopy. Taking into account the literature data and our own results, curettage of the uterine cavity was performed against the background of antibiotic therapy, as well as with the addition of anti-inflammatory, desensitizing, and antianemic treatment to the therapy.The hysteroscopic picture of the endometrium varied depending on the nature and volume of uterine bleeding. The endometrium was thickened, in the form of folds of various heights of a pale pink color. The endometrium is represented by numerous folds of the mucosal surface with a wide base with uneven edges in the form of ridges 10 to 15 mm high. A pronounced vascular pattern was determined. The hue of the folds was determined from pale pink to bright red. Changes in the flow and pressure of the injected fluid changed the rate of movement of the mucous membrane. Focal lesions of the mucosa were registered; the orifices of the fallopian tubes were visualized.Thickening and swelling of the mucous membrane of a pale pink color in the form of numerous folds of various heights, in the form of polypoid growths, the presence of a large number of gland ducts, the undulating movement of the endometrium with a change in the rate of fluid flow into the uterine cavity - the phenomenon of "underwater plants" was detected a little less than in most patients - 41 (77.4%). In some patients, these pictures were found to have endometrial polyps in combination with fragments of endometrium that did not slough off - 18 (22.6%). In 10 (18.9%) patients, the hysteroscopic picture was characterized by the presence of a thin pale endometrium with small hemorrhages in separate areas, the presence of individual fringed patches of pale pink mucosa mainly in the area of the uterine fundus and tubal angles. This hysteroscopic picture occurred among patients with mainly prolonged uterine bleeding.

| Figure 1. Hysteroscopic picture of endometrial hypertrophy |

3. Results of the Study

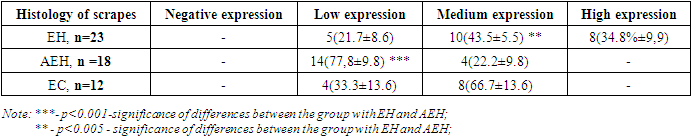

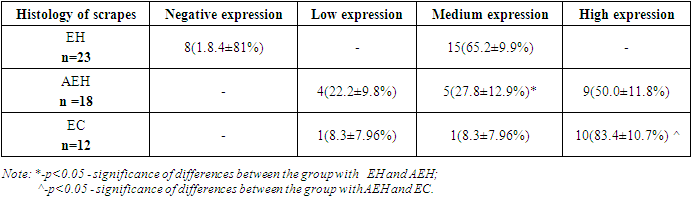

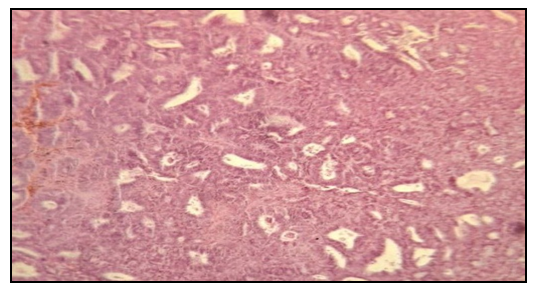

- The study of the morphology of scrapings of the uterine cavity showed the following distribution according to histological diagnoses:1. simple endometrial hyperplasia, n=23 (43.4%);2. atypical endometrial hyperplasia, n = 18 (34%);3. endometrioid carcinoma, n=12 (22.6%).In 23 patients, simple endometrial hyperplasia was histologically verified. In the study medications, there was an absence of separation of the endometrium into compact and spongy layers (Fig. 2). Also, there was no regularity in the distribution of glands in the stroma. Numerous glands of various shapes and sizes are unevenly distributed in the stroma, in separate areas with weakly expressed folds in the direction of the lumen of the glands. There were cystic enlarged glands and unevenly distributed in the stroma, some glands were cystically distended.

| Figure 3. Histological examination. Atypical endometrial hyperplasia. Staining: Hematoxylin eosin 10х10 |

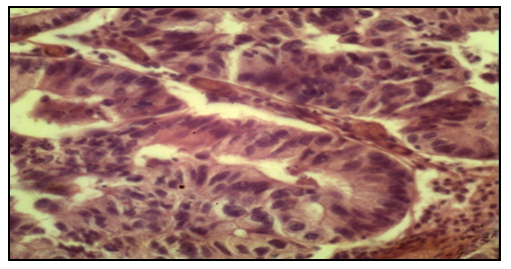

| Figure 4. Histological examination. endometrioid carcinoma. Staining: Hemotaxillin eosin 10х10 |

|

|

|

4. Conclusions

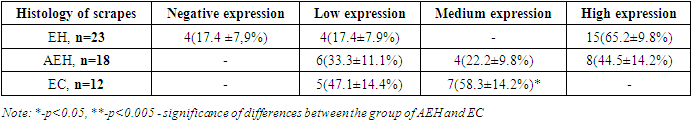

- The study of correlations between the studied indicators of the proliferative activity of endometrial cell populations in postmenopausal women with uterine bleeding in relation to each of the diagnosed endometrial pathologies showed the following.In the group of patients with simple endometrial hyperplasia, a significant positive correlation was found between the indices of CD138, an inflammatory marker, with this pathology of the endometrium (r = 0.73; p<0.05).The results of the study also showed a correlation between CD138, an inflammatory marker, and the presence of endometrioid carcinoma (r=0.87; p<0.05). Also, a positive correlation was noted between p53 and simple endometrial hyperplasia r=0.76 and endometrioid carcinoma r=0.75.A significant positive correlation of the proliferation marker Ki 67 - r=0.86 is observed in endometrioid carcinoma, as well as in simple endometrial hyperplasia - r=0.62. As for endometrial hyperplasia with atypia, all three markers showed the absence of any correlation – r=0.0; r=0.13; r=-0.12.The results of this section of the study indicate a rather high sensitivity of both CD138 - 78% and Ki67 - 83% in the diagnosis of endometrial pathology in postmenopausal women [RI 91.17-97.95].The study of these markers of the proliferative activity of endometrial cell populations enables to use them with a high degree of probability in the diagnosis and choice of tactics for the treatment of uterine bleeding in the postmenopausal period.All patients with atypical hyperplasia and endometrioid carcinoma were sent for a consultation with an oncogynecologist for surgical treatment.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML