-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2023; 13(6): 775-786

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20231306.03

Received: Jun. 1, 2023; Accepted: Jun. 12, 2023; Published: Jun. 14, 2023

Awareness, Knowledge, Attitude and Clinical Experience of Consultant Orthodontists and Orthodontic Resident Doctors about Phantom Bite Syndrome

Emmanuel Chukwuma 1, Benjamin O. Okino 1, Chikamaram O. Okino 2, Elfleda A. Aikins 3, Chukwudi Ochi Onyeaso 4

1Department of Child Dental Health, University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital, Port Harcourt, Nigeria

2Department of Oral Pathology and Medicine, University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital, Port Harcourt, Nigeria

3Senior Lecturer/Consultant Orthodontist, Department of Child Dental Health, Faculty of Dentistry, College of Health Sciences, University of Port Harcourt/University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital, Port Harcourt, Nigeria

4Professor of Orthodontics/Consultant Orthodontist Department of Child Dental Health, Faculty of Dentistry, College of Health Sciences, University of Port Harcourt/University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital, Port Harcourt, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Chukwudi Ochi Onyeaso , Professor of Orthodontics/Consultant Orthodontist Department of Child Dental Health, Faculty of Dentistry, College of Health Sciences, University of Port Harcourt/University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital, Port Harcourt, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Background: Available information show that dental treatments of PBS patients have led to the worsening, if not the main trigger, of this condition, thereby underscoring the need for its prompt diagnosis. This study aimed at assessing the awareness, knowledge, attitude and clinical experience of Nigerian Orthodontic community with PBS patients. Materials and Methods: Using the Nigerian Association of Orthodontists (NAO) social platform, a 14-item questionnaire was served both online (Google Forms) and by physical distribution with 64 of the served 112 filling and returning the questionnaire, giving a response rate of 57.1%. The data collection lasted for 6 months and was analyzed with SPSS version 25, using both descriptive, Pearson Chi-square statistics and One-Sample T test as the significance level was set at P < .05. Results: Both the consultant orthodontists and the orthodontic resident doctors had very poor awareness of PBS, which was very significant with respect to the first author of PBS (P < .000). Although the orthodontic consultants had insignificant better knowledge than the orthodontic residents, both had generally significant poor knowledge of PBS symptoms (P < .000). Their attitude towards increasing the awareness and knowledge of PBS in Nigeria was generally significantly very positive (P < .000), but with significantly low clinical experience (P < .000). Conclusion/Recommendation: The participants had poor awareness with significantly poor knowledge and clinical experience with PBS, but had encouraging positive attitude towards promoting awareness and knowledge of the condition. Nigerian Consultant orthodontists should play central role in ensuring the incorporation of PBS into the orthodontic education curriculum in the country.

Keywords: Phantom Bite Syndrome, Nigeria Orthodontic Community, Awareness, Knowledge, Attitude, Clinical Experience

Cite this paper: Emmanuel Chukwuma , Benjamin O. Okino , Chikamaram O. Okino , Elfleda A. Aikins , Chukwudi Ochi Onyeaso , Awareness, Knowledge, Attitude and Clinical Experience of Consultant Orthodontists and Orthodontic Resident Doctors about Phantom Bite Syndrome, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 13 No. 6, 2023, pp. 775-786. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20231306.03.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- About 46 years ago, Marbach [1] described what he then called a subgroup of so-called temporomandibular joint (TMJ) patients who nomadically pass from one dentist to another seeking “bite correction.” According to him, while this behaviour may start at any time, it often begins in late adolescence following completion of initial orthodontic treatment. He then referred to the condition as a mono-symptomatic hypochondriacal psychosis, and raised three important questions in the understanding of the condition from the histories of the patients he presented as follows: (1) what does the notion of a “correct bite” symbolize or mean to these patients, and why does it start in adolescence? (2) Why do they inexorably pursue, often for many years and at great cost, this goal of a “correct bite”? (3) why do not the repeated treatment failures discourage the patients from pursuing further treatment? These led to the development of the Marbach’s seven diagnostic indicators of phantom bite syndrome patients with the additional comments from Kelleher et al [2,3,4]. The seven diagnostic indicators [4] are: (1) Perceived dental knowledge - intensely involved and have some knowledge of dental anatomy, physiology and dentistry. They often know bits of dental jargon, and use abbreviations or terminology regarding occlusion. Will talk endlessly about their 'bite' or 'occlusal' problems, or their 'issues around' the shape, colour and contour of their teeth, or various restorations and suggest how they should be changed, or altered, to correct their problems; (2) Keep study casts and detailed clinical records - these patients often present at the first, or at subsequent, appointments with numerous diagnostic casts that they have accumulated over the years. They will point at which parts of which cusps need adjustment to fix the problem. Diagrams, some beautifully illustrated, are sometimes presented for inspection; (3) Severe symptoms all being due to their occlusion - Complain of, or believe that, they have a serious bite or cosmetic defect. They have an ongoing and unshakeable belief that their 'bite or occlusion' is wrong, or that their bite looks wrong; (4) Sustained delusion - The delusion is sustained for many years in spite of sympathetic explanations and careful reassurance. Apart from the initial placebo effect these particular patients’ symptoms are rarely improved by occlusal splint therapy, orthodontics, occlusal adjustments or 'equilibration', or prosthodontic interventions of different types by different dentists or various specialists; (5) Unwilling to accept referral to, or help from, psychiatrists - Resist the suggestion very strongly that their problem is psychiatric in origin and therefore they refuse to accept psychiatric help, or to be referred for psychiatric assessment. Patients are convinced that previous dentists have caused their problems and that further 'bite' or orthodontic or prosthodontic treatment, or surgical treatment, if it were just to be done correctly, would rectify all their bite and/or other issues; (6) Socio-economic status - High socio-economic status patients undergo extensive restoration of the occlusion indefinitely (because they can afford it). Patients of more moderate means are limited by financial constraints but still have uncontrollable impulses to have various people 'correct their bite', in the belief that the right occlusal therapy, or the right articulator, will solve their agony. Such dilemmas produce desperate people and they often seek multiple referrals to hospitals where treatment might be free, or they sometimes borrow money in order to have treatment of varying complexity, stability or irretrievability; and (7) Intelligent Quotient (IQ) - These problems often occur in patients with above average intelligence and often very articulate or literate about their problems and what needs to be done.There is no known prevalence or incidence of Phantom bite syndrome [4], but considering the fact that ‘incorrect occlusion’ or ‘incorrect bite’ is usually the central complaints of such patients and the desire for ‘ideal’ bite is also usually the case here, it becomes very necessary that orthodontists should be aware of such patients so as to avoid unnecessary active treatments that could worsen their complaints. In 2011, Ligas et al [5] carried out a survey of 4,000 orthodontists in America with only 337 completing the survey, and only 50% of this group were familiar with the term ‘phantom bite’. Despite the increasing attention in the literature [6-23] about the Phantom bite syndrome or occlusal dysesthesia (dysaesthesia) because of the obvious management implications when not diagnosed on time, there is paucity of published data on this from Africa, especially Nigeria. Therefore, this study aimed at assessing the awareness, knowledge, attitude and possible clinical experience of Nigerian orthodontic community about Phantom bite syndrome (occlusal dysesthesia).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population and Design

- A questionnaire-based a cross-sectional study design was conducted among the orthodontic community in Nigeria – specialists and orthodontic residents. The orthodontic resident doctors are currently undergoing postgraduate trainings at the various postgraduate training institutions in Nigeria (teaching hospitals), and are preparing for the professional examinations of either the West African College of Surgeons or the National Postgraduate Medical College of Nigeria or both. The consultant orthodontists are those who had earlier passed the final specialist examinations of either the West African College of Surgeons or the National Postgraduate Medical College of Nigeria or both who are mostly employed in the Universities and tertiary healthcare institutions as Consultants Orthodontists for patient care, training of younger doctors, research activities and community service.

2.2. Sample Collection

- Using a 14-item questionnaire (See Appendix), the data collection lasted between October 2022 and April 2023. Both physical and online (Google forms) distributions of the questionnaire were used within the 6-month period, while ensuring that no respondent filled the questionnaire more than once. The official platform of the Nigerian Association of Orthodontists (NAO) had 115 members (both Consultants Orthodontists and Orthodontic Resident doctors) as at the time of this survey. One hundred and twelve (112) of them were served the questionnaire and 64 of them filled and returned the questionnaire, giving a response rate of 57.1%. The final sample (64 participants) was drawn from the following training centres in Nigeria: University College Hospital (UCH), Ibadan, Oyo State, Lagos University Teaching Hospital (LUTH), Lagos, Lagos State, Lagos State University Teaching Hospital, Lagos State, Obafemi Awolowo University Teaching Hospital (OAUTH), Ile-Ife, Osun State, University of Benin Teaching Hospital (UBTH), Benin City, Edo State, University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital (UNTH), Enugu, Enugu State, University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital (UPTH), Port Harcourt, Rivers State, University of Calabar Teaching Hospital (UCTH), Calabar, Cross River State, Amino Kano Teaching Hospital (AKTH), Kano, Kano State, and the Usman Danfodio Teaching Hospital (UDTH), Sokoto, Sokoto State.

2.3. Objectives of the Study

- 1. To determine the level of awareness of the PBS among Consultant Orthodontists and Orthodontic Resident doctors.2. To determine the knowledge of PBS among Consultant Orthodontists and Orthodontic Resident doctors.3. To determine the attitude of the Consultant Orthodontists and Orthodontic Resident doctors towards the PBS.4. To determine the clinical experience of Consultant Orthodontists and Orthodontic Resident doctors in Nigeria with PBS.

2.4. The Null Hypotheses

- The following null hypotheses were generated and tested:1. There would be a significantly poor general awareness of the Phantom Bite Syndrome among the Consultant Orthodontists and the Orthodontic Resident doctors in Nigeria, including the knowledge of the first author of Phantom Bite Syndrome (Ho1).2. There would be significantly poor general knowledge of the symptoms of Phantom bite syndrome among the Consultant Orthodontists and the Orthodontic Resident doctors (Ho2).3. There would be no significant difference in the knowledge of the symptoms of Phantom bite syndrome between the Consultant Orthodontists and the Orthodontic Resident doctors (Ho3).4. There would be no positive attitude among the Consultant Orthodontists and the Orthodontic Resident doctors towards increasing the awareness and knowledge of Phantom bite syndrome in Nigeria (Ho4).5. There would not be significant proportion of the Consultant Orthodontists and the Orthodontic Resident doctors with clinical experience about PBS cases (Ho5).

2.5. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.5.1. Inclusion Criteria

- 1. Only the qualified Orthodontists, that is, dental professionals who have postgraduate.2. Qualifications of either the West African College of Surgeons or that of the National Postgraduate College of Nigeria or both in Orthodontics and are registered as specialists by the Medical and Dental Council of Nigeria (MDCN), and Orthodontic Resident doctors registered as dental surgeons by the MDCN were involved in this work.3. Such an Orthodontist must have been employed or qualified to be employed as a lecturer in a Nigerian University and/or a Consultant Orthodontist in a teaching hospital or any hospital, while the Orthodontic Resident doctor must be formally employed in an accredited training institution in Nigeria for the postgraduate orthodontic education programmes of either the West African College of Surgeons or the National Postgraduate Medical College of Nigeria or both.

2.5.2. Exclusion Criterion

- Any dental professional who was yet to obtain any postgraduate qualifications in orthodontics, as well as those who were not formally admitted into residency programme in orthodontic education in any accredited institution in Nigeria.

2.6. Weighting or Scoring of the Questionnaire Options

- Every Correct Answer received 5 scores; ‘Do not know’ option had 3 scores, while each Wrong Answer got 2 scores.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

- The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (IBM SPSS) version 25 was used to analyze the data. In addition to the descriptive statistics used, the Pearson Chi-square test and One-Sample T-test were employed in the analysis as appropriate. The significance level was set at P < 0.05.

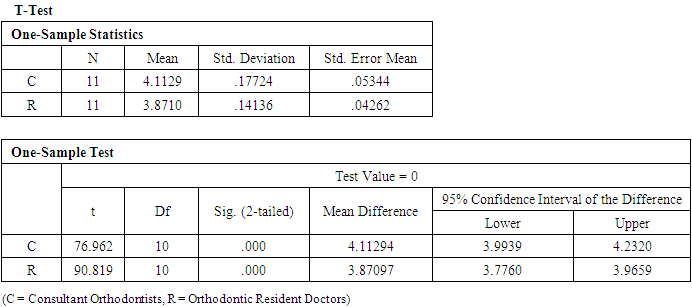

3. Results

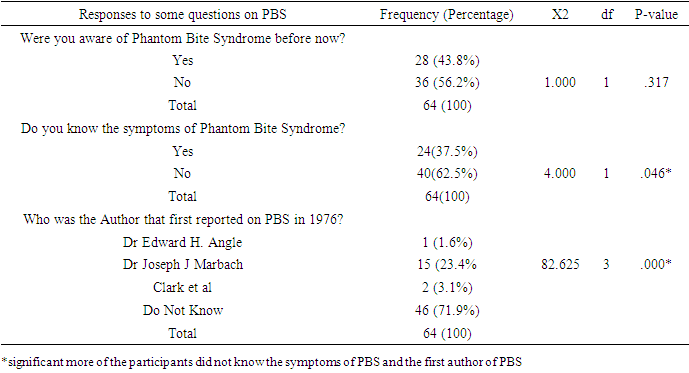

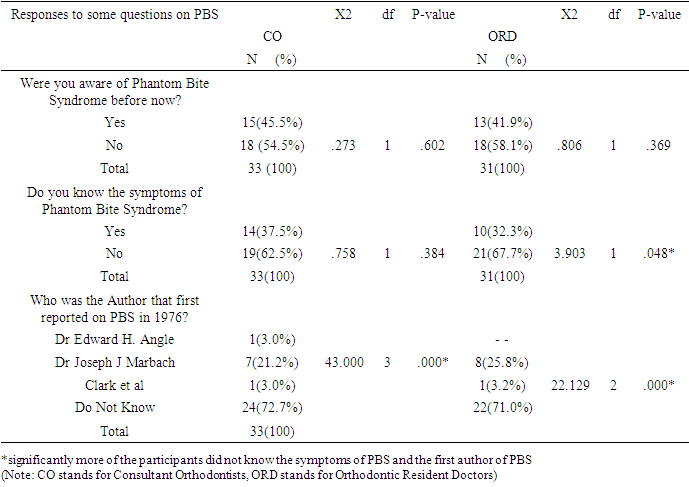

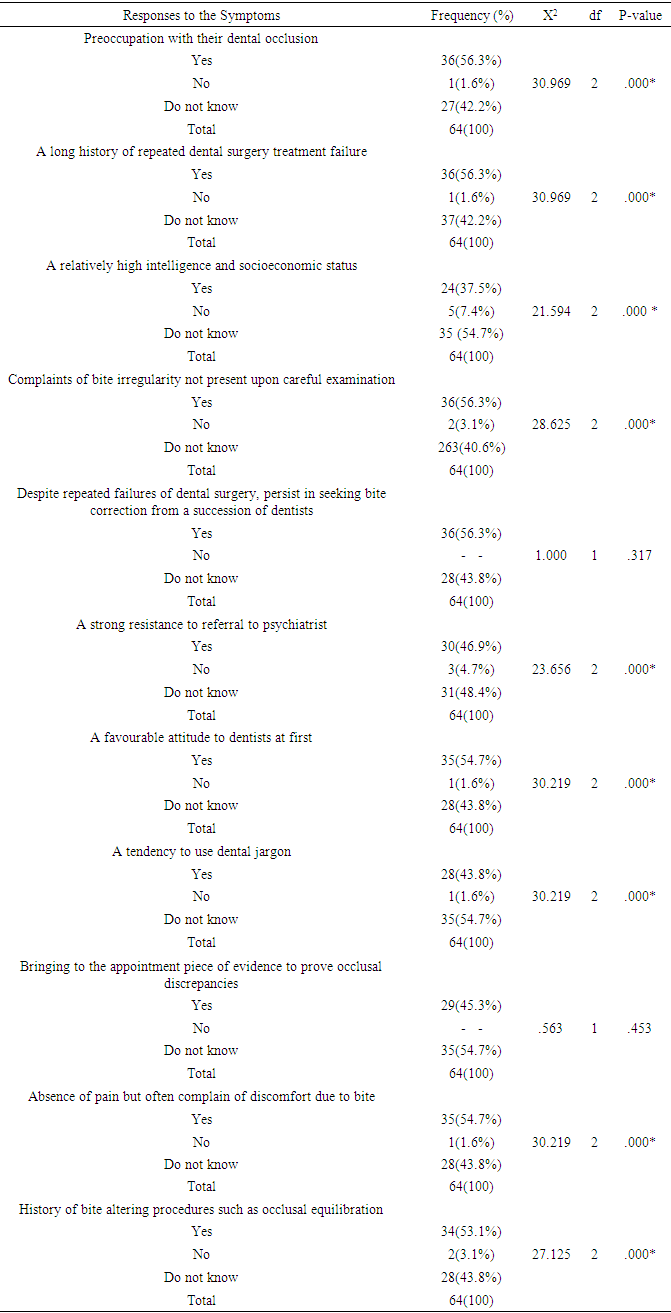

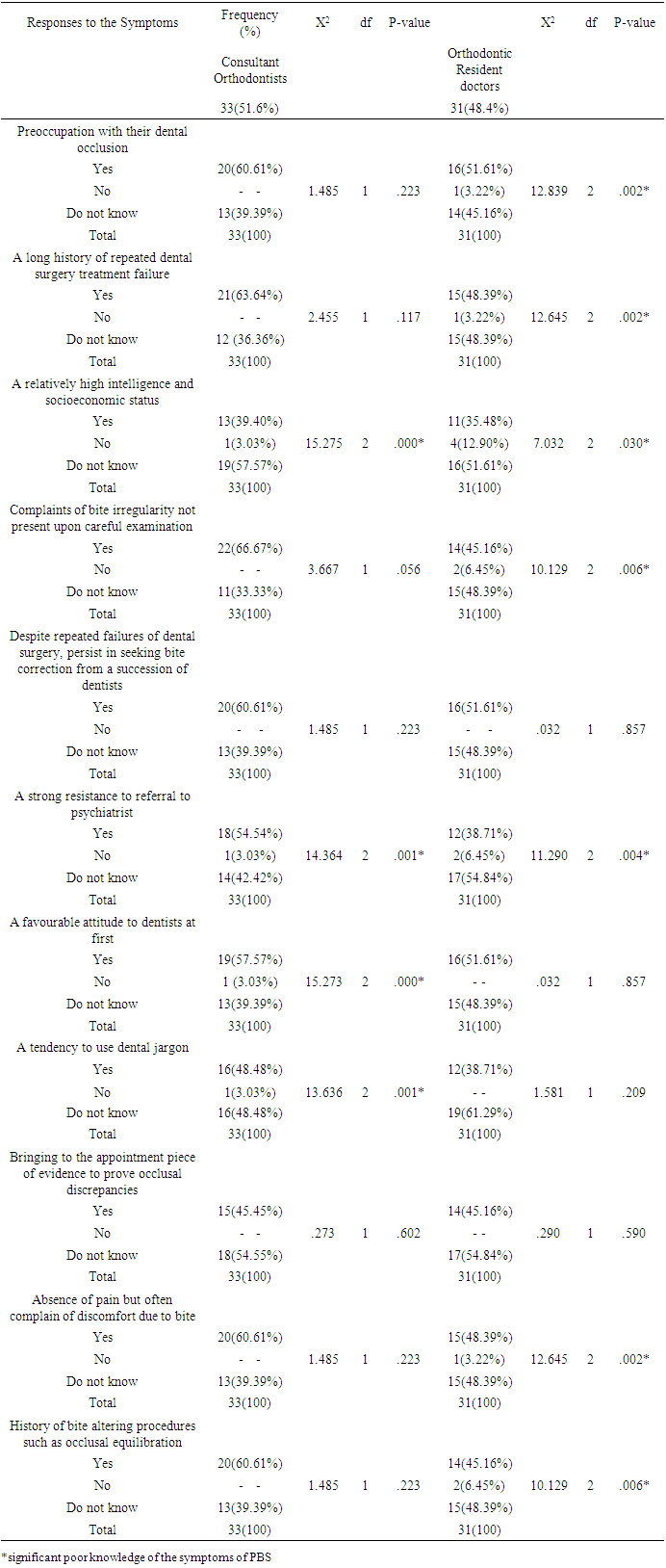

- A total of sixty-four (64)) participants were recruited into the study consisting of 36 (56.25%) females and 28 (43.75%) males with the age range of 28 to 65 years (mean age of 43.44 ± 9.68 SD). Tables 1a and 1b show the responses of the participants to the questions on awareness of Phantom Bite Syndrome (PBS) and the knowledge of the first author concerning PBS. There was no statistically significant (P > 0.05) difference between those who claimed to have been aware of PBS before this study and those who claimed otherwise. Meanwhile, significantly low proportion of the participants claimed to know of PBS symptoms and first author of PBS. The first hypothesis of this study is accepted.

|

|

|

|

|

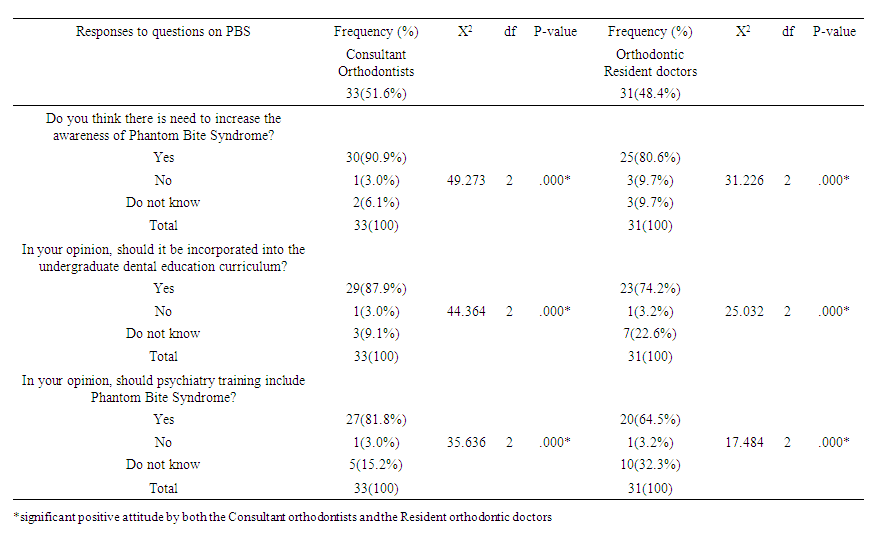

| Table 5. Attitude of the Participants (Consultants) to Phantom Bite Syndrome (PBS) |

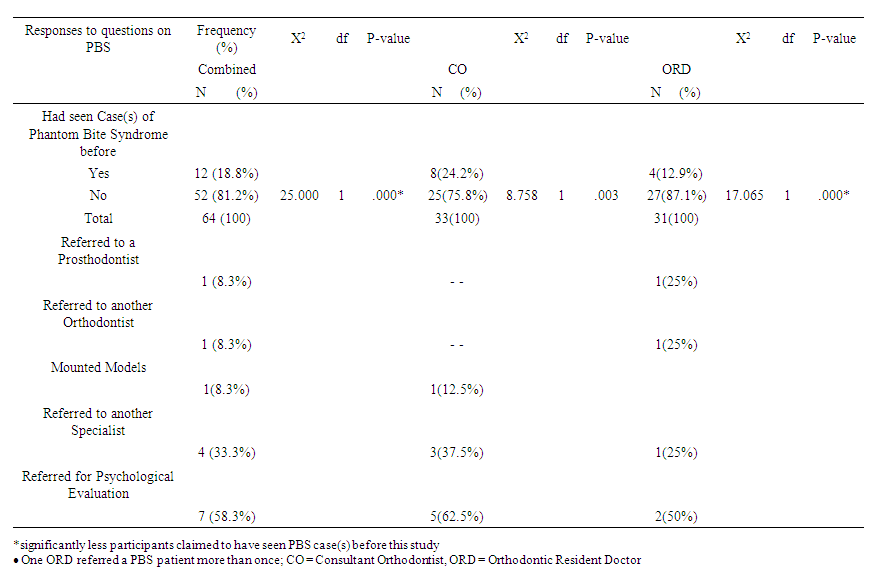

| Table 6. Clinical experience of the participants with PBS patients |

4. Discussion

- The present study on Phantom Bite Syndrome (PBS) with respect to the Nigerian orthodontic community has shown that the consultant orthodontists and the orthodontic resident doctors were unaware of PBS before the current survey and significantly not aware of the first author of PBS in 1976. The same participants significantly had poor knowledge of the symptoms of PBS, which was significantly not difference between the professional consultants and the resident doctors. However, their clinical experience with PBS was found to be significantly low. Meanwhile, both the consultant orthodontists and the orthodontic resident doctors exhibited encouraging positive attitude towards increasing the awareness and knowledge of this phenomenon in Nigeria through the incorporation of the teaching of it through the dental and medical curricula in Nigerian dental and medical schools. In 2011, Ligas et al [5] reported that approximately 50% of the responding orthodontists in the United States of America (USA) were unfamiliar with Phantom bite syndrome (PBS). The current Nigerian study found over 56% of the orthodontists and the orthodontic resident doctors (postgraduate orthodontic doctors) were unaware of this condition before the survey, while over 54% of the consultant orthodontists showed that they were ignorant of the condition, as over 76% of the Nigerian respondents did not know about Dr Joseph J. Marbach who first reported on this phenomenon in 1976. Considering the fact that the teaching and practice of orthodontics is relatively young in Nigeria when compared with the USA, the current finding of this Nigerian study is not surprising. Although the pattern of clinical experience with PBS could be comparable to that of Ligas et al [5] findings, it is clear that the US orthodontists saw more PBS cases than the figure in our present Nigerian study.The importance of the knowledge of the symptoms of PBS has been severally highlighted to avoid initiating unwarranted dental treatments for such a patient or complicating already bad situations [2-23]. The current generally poor knowledge of PBS symptoms calls for intentional plan to increase awareness and knowledge of this syndrome among dentists, especially the orthodontists so as to sharpen their consciousness and ability to diagnose such cases because of the fact that many of such patients complain of occlusion and often demand orthodontic care. Relatively recent report of PBS cases by Watanabe et al [17] revealed that all the patients who were attended to in their clinics strongly were convinced that occlusal correction was the only solution to their symptoms, including the symptoms of discomfort in other body parts. The findings of our present study concerning the clinical experience of the orthodontists show clearly that this is very limited and there could have been more of such patients but were possibly missed due to the present poor awareness and knowledge of the condition leading to the invariably low index of suspicion by the orthodontic community for such patients.Watanabe et al [17] commented that the misleading perceptions of their patients were uncorrectable, and repeated dental treatments exacerbated their complaints. Moreover, the dentists overlooked the psychotic histories of the patients, while the comorbid psychosis resulted in a strict demand for dental treatment by the patients. The comorbid psychosis or psychological factors involved in such patients have been highlighted by many other authors [3-23]. Interestingly, most of the cases indicated by the orthodontic professionals in this survey received referrals for psychological evaluation. In addition, our respondents in this study showed positive attitude towards PBS by agreeing that psychiatry curricula in our medical schools should incorporate the teaching of PBS. In addition, the positive attitude of the respondents in this Nigerian study is encouraging as significant majority of them agreed that our dental schools should incorporate PBS teaching in their curricula, which holds the potential of increasing the awareness and bridge the observed knowledge deficit about this phenomenon for better management of such cases when they are diagnosed. This Nigerian study revealed that one consultant orthodontist mounted a model for one the cases, which could reinforce the erroneous belief that orthodontic treatment was necessary to address the patient’s perceived occlusal problem. This is obviously not a correct management attempt. Imhoff et al [20] reported that one of the treatments for PBS is nontreatment apart from dental treatments in order to avoid unnecessary change in occlusal contacts. According to Watanabe et al [17], dentists should keep in mind that the clinical characteristics of underlying psychosis may also affect patients complaining of PBS more persistently, and hidden psychosis could be reflected by uncorrectable wrong convictions, unreasonable attitude, strict persistence, and belligerent demands. In addition, they reported that all the cases presented iatrogenic orthodontic progression that generally produced substantial occlusal changes overall, especially for the cases with long psychotic history or young onset of psychosis and the presence of medically unexplained symptoms, dentists should be more cautious before providing orthodontic treatments [17]. In summary, their report presented PBS cases with psychosis that suggested that repeated dental treatments and comorbid psychosis exacerbate PBS. In addition, the PBS patients’ persistent demands were a reflection of comorbid psychosis that led dentists to perform numerous procedures. In the management of PBS, several patients with PBS respond to psychopharmacotherapy with antidepressants [12,14,17]; however, treatment with antidepressants for PBS would become extremely difficult when the patients have comorbid psychosis. It is important to note that early detection of underlying psychosis or psychiatric disorders and avoidance of damage to occlusion are integral, while the prompt diagnosis and collaboration betweenpsychiatrists and orthodontists or dentists are central to help prevent complications in PBS cases with psychosis. The absence of dental triggers for PBS would predict the presence of psychiatric comorbidities [12]. Dentists should request further psychiatric history; furthermore, they should not skip this portion of history-taking or underestimate the self-declaration of patients of the same [17].The Strengths and Limitations of this StudyThe good representative nature of the study sample is a plus as the participants were drawn from all the accredited training institutions in Nigeria for both the West African College of Surgeons and the National Postgraduate Medical College of Nigeria located in every part of the country. Although the questionnaire was a product of extensive research on the subject, it was not subjected to face or content validity.

5. Conclusions

- 1. The consultant orthodontists and the orthodontic resident doctors were generally very much unaware of PBS, which was very significant in relation to the first author of PBS in 1976.2. Although the consultant orthodontists had generally fairly better knowledge of the symptoms of PBS than the orthodontic resident doctors, both had significantly poor knowledge.3. All the participants had significantly positive attitude towards increasing the awareness and knowledge of PBS in Nigeria through the incorporation of PBS teaching in the curricula of our medical and dental schools.4. The clinical experience of all the participants about PBS was found to be significantly low generally.

6. Recommendations

- As a result of the findings of this survey, the following recommendations could be helpful:1. Consultant orthodontists should seriously consider making sure that this subject matter is incorporated into the training curricula of both undergraduate and postgraduate orthodontic education programmes of our dental schools and the West African College of Surgeons and the National Postgraduate Medical College of Nigeria.2. Although the PBS involves every discipline in dentistry, the Nigerian orthodontists should try and play a major role in increasing the awareness of this phenomenon in the country because of the usual complaints of such patients about their occlusion.3. Considering the growing aetiological theories of this condition and the need for multidisciplinary team approach in the management of such patients, the Consultant Orthodontists should play a central role in coordinating such team management by ensuring that the Psychiatrists, Psychologists, Neurologists, Oral Medicine specialists, other dental specialties, etc are involved for the best possible care of PBS patients.4. Nigerian Association of Orthodontists (NAO) could help in creating awareness and knowledge of this phenomenon through routine seminars and professional public lectures, especially for the General dental Practitioners.

Appendix

- QUESTIONNAIRE ON PHANTOM BITE SYNDROMEPlease, your help as you freely participate in this study is highly appreciated. This is purely for research purposes only and your responses will be confidently handled accordingly. Thanks a lot for providing your honest responses in this questionnaire. God bless you richly.SECTION A1. Age ------- 2. Gender -------- 3. Name of Hospital where you work: ------------------------4. Year of undergraduate graduation: ------------ 5. Consultant Orthodontist ----------- / Resident in Orthodontics ----------------------6. How long have you been practising orthodontics/Dentistry? ----------------------------SECTION B7. Where you aware of Phantom bite syndrome before now? Yes ------- No ----------8. Which of these researchers (authors) reported Phantom bite first in 1976? (a) Dr Edward H. Angle ------ (b) Dr Joseph J. Marbach ------ (c) Clark et al -------- (d) Jagger and Korszun -------------- (e) Do not know ----------------------------- 9a. Have you ever seen any case(s) of Phantom bite syndrome before? Yes ----- No ------9b. If Yes, how did you manage it? a. Referred to a Prosthodontist? Yes --------- No ----------------b. Referred to another Orthodontist? Yes ------------- No ------------c. Referred for psychological evaluation? Yes --------- No -----------d. Referred to another Specialist? Yes ----------- No -------------------e. Sent back to the referring doctor? Yes --------- No ------------------f. Started orthodontic treatment? Yes ----------- No -------------------g. Mounted models, did occlusal analyses, gave orthodontic treatment Yes ---- No ---h. Referred to the Dental Practitioners Yes ------- No --------------i. Others (please specify) ----------------------------------------------------------------------10. Do you know the symptoms of Phantom bite syndrome? Yes ------- No -----------11. Which of these is/are part of the symptoms of Phantom bite syndrome?a. Preoccupation with their dental occlusion and an enormous belief that their dental occlusion was abnormal: Yes ---------------- No --------- Do not know -------------b. A long history of repeated dental surgery treatment failures with persistent requests for the occlusal treatment that they are convinced they need: Yes -------- No --------- Do not know ------------------c. A relatively high intelligence and socioeconomic status enabled them to undergo endless costly and time consuming dental treatments: Yes --- No ---- Do not know -------d. Complaints of bite irregularity not present upon careful examination: Yes -- No --- Do not know ------------e. Despite repeated failures of dental surgery, persist in seeking bite correction from a succession of dentists: Yes ---------- No --------- Do not know ----------------f. A strong resistance to referral to psychiatrists and stick to dental procedures: Yes --------- No ----------- Do not know --------------g. A favourable attitude to dentists at first, gradually blaming them for the exacerbated symptoms, finally dropping out with disappointment: Yes --------- No --------- Do not know -----------h. A tendency to use dental jargon: Yes ----------- No -------- Do not know -----------i. Bringing to the appointment pieces of evidence to prove occlusal discrepancies (radiographs, study cast, temporary crowns, mouthpieces, etc.): Yes ----- No –--- Do not know ----------j. Absence of pain but often complaints of discomfort due to bite: Yes -- --No –--- Do not know --------k. History of bite-altering procedures such as occlusal equilibration, multiple restorations or repeated orthodontic treatments: Yes ---- No ---- Do not know ------12. In your opinion, do you think there is need to increase awareness of Phantom bite syndrome in Nigerian orthodontic/dental/ psychiatric practice? Yes ------ No ------- Do not know --------------------------------13. In your view, should undergraduate dental education curriculum include Phantom bite syndrome? Yes ---------------- No --------------------- Do not know -------------------14. In your view, should Psychiatry training include Phantom bite syndrome? Yes ----- No --------- Do not know -------------------THE END

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML