-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2023; 13(5): 721-729

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20231305.37

Received: May 11, 2023; Accepted: May 25, 2023; Published: May 27, 2023

Phantom Bite Syndrome: Awareness, Knowledge and Attitude of Some Dental Consultants

Chikamaram O. Okino1, Benjamin O. Okino2, Emmanuel Chukwuma2, Chukwudi O. Onyeaso3

1Department of Oral Pathology and Medicine, University of Port HarcourtTeaching Hospital, Port Harcourt, Nigeria

2Department of Child Dental Health, University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital, Port Harcourt, Nigeria

3Department of Child Dental Health, Faculty of Dentistry, College of Health Sciences, University of Port Harcourt/University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital, Port Harcourt, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Chukwudi O. Onyeaso, Department of Child Dental Health, Faculty of Dentistry, College of Health Sciences, University of Port Harcourt/University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital, Port Harcourt, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Background: Although Phantom Bite Syndrome patients are not common, the consequences of not promptly diagnosing the phenomenon when it presents and attempting misguided management of such could be severe both to the patient and the poorly informed dental surgeon. Objective: This study aimed at assessing the awareness, knowledge and attitude of some dental consultants/examiners toward Phantom Bite Syndrome (PBS). Materials and Methods: Self-administered questionnaire with 14 questions were distributed to the dental consultants/examiners that participated in the October 2022 examinations of the West African College of Surgeons held at the University College Hospital, Ibadan. Some who did not participate in the examinations were contacted online through their social (WhatsApp) platforms using Google forms. The survey lasted between October, 2022 and April, 2023. The data was analyzed using Statistical Package of Social Sciences (SPSS) version 25, while descriptive statistics, chi-square test and one-sample T-test were employed with a significance level set at P < 0.05. Results: Generally, significant poor awareness (P = 0.000) and significant poor knowledge of the symptoms of PBS (P = 0.000) were obtained among the dental specialists, which significantly remained the same irrespective of how long ago when they graduated from the dental schools. They showed an encouraging positive attitude towards improving awareness and knowledge of this syndrome in the sub-region. Conclusion: This study has determined poor awareness and knowledge of Phantom bite syndrome among dental consultants, but their encouraging positive attitude toward the promotion of the awareness and knowledge of this phenomenon in our region, including the future dental surgeons and psychiatrists.

Keywords: Phantom Bite Syndrome, Awareness, Knowledge, Dental Consultants/Examiners

Cite this paper: Chikamaram O. Okino, Benjamin O. Okino, Emmanuel Chukwuma, Chukwudi O. Onyeaso, Phantom Bite Syndrome: Awareness, Knowledge and Attitude of Some Dental Consultants, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 13 No. 5, 2023, pp. 721-729. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20231305.37.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Phantom Bite Syndrome (PBS) was first described by Marbach over 40 years ago as a mono-symptomatic hypochondriacal psychosis [1,2]. He used the term to describe a prolonged syndrome in which patients report that their ‘bite is wrong’ or that ‘their dental occlusion is abnormal’ with this causing them great difficulties. This strong belief about ‘their bite’ being the source of their problems leads to them demanding, and subsequently getting, various types of dentistry carried out by multiple dentists and ‘specialists’ [3].Unfortunately, even after exhaustive, painstaking, careful treatment, none of the dental treatments manages to solve their perceived ‘bite problems,’ and it takes a toll on their quality of life causing, career disruption, financial loss and suicidal thoughts [3,4]. This is because they suffer from a psychiatric illness involving a delusion into which they continue to lack insight, despite the failures of often sophisticated dental treatments [4]. Dental practitioners, or other specialists, who suspect that they might be dealing with such a problem should refer these patients early on for psychological or psychiatric specialist management by an appropriate specialist such as a general dental practitioner or an orthodontist or oral medicine specialist, etc within the secondary care settings, preferably before they get trapped in the time-consuming quagmire of their management [4].Phantom Bite Syndrome (PBS), also called occlusaldysesthesia, is characterized by persistent non-verifiable occlusal discrepancies [5]. In general, patients with PBS are quite rare but distinguishable if ever encountered [4]. Since Marbach reported the first two cases in 1976 [1], there have been dozens of published cases regarding this phenomenon [4]. Despite the lack of official classification and guidelines, many authors agreed on the existence of a PBS "consistent pattern" that clinicians should be made aware [4]. Nevertheless, the treatment approach has been solely based on inadequate knowledge of aetiology, in which none of the proposed theories are explained in all the available cases [4,5]. The clinically focused review by Tu et al [4] affirmed the critical role of enhancing dental professionals' awareness of this condition and suggested a comprehensive approach for PBS, provided by a multidisciplinary team approach of dentists, psychiatrists and psychotherapists. According to Watanabe et al. [6], Phantom bite syndrome (PBS) is considered as the preoccupation with dental occlusion and the continual inability to adapt to changed occlusion. These patients constantly demand occlusal corrections and undergo extensive and excessive dental treatments [6]. Watanabe et al [6], reported that their patients were strongly convinced that occlusal correction was the only solution to their symptomsincluding the symptoms of discomfort in other body parts. Their misleading perceptions were persistent, and repeated dental treatments Hitherto, exacerbated their complaints. Moreover, the dentists overlooked the psychotic histories of the patients, while the comorbid psychosis resulted in a strict demand for dental treatment by the patients [6]. Psychological distress is remarkable even in PBS cases without any psychiatric history and could result in serious consequences on patients' life, even suicidal thoughts [3,4].Typical dental treatments normally make the PBS symptoms worse, even if they could achieve temporal improvement [3,7]. PBS is rare but distinguishable, if ever encountered, and for affected patients’ dental treatment would not be effective and should be avoided, since it often affects patients iatrogenically for the worse [4,8]. In addition, after the initial reports byMarbach [1,2], there have been several other related publications from different countries [9-19]. Previously, there is no known related report from Nigeria just like most African countries. There is need to increase awareness of this condition among dental teachers/trainers and during dental education, at least in the West African sub-region. This is desirable due to the growing globalization and to prevent extensive, iatrogenic, or non-sustainable dental treatment being undertaken the affected patients in a vain attempt to treat their supposed dental problems when, in fact, these are really due to underlying mental health issues [3,4,6]. Therefore, this study aimed at assessing the awareness, knowledge and attitude of some dental consultants/examiners towards Phantom Bite Syndrome because they are the teachers/trainers of both undergraduate and postgraduate dental students in Nigeria and other West African countries.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population Design

- A questionnaire-based cross-sectional study design was conducted among the Dental Consultants involved in the training and examination of resident (postgraduate) dental surgeons in the West African sub-region both for the West African College of Surgeons and the National Postgraduate Medical College of Nigeria.

2.2. Sample Collection

- The period of data collection lasted between October 2022 and April 2023, using a questionnaire with 14 questions. Both physical and online (Google forms) distributions of the questionnaire were used within the 6-month period. Most of the sample was gathered during the October 2022 Examinations period of the West African College of Surgeons at the University College Hospital (UCH), Ibadan, Oyo State, Nigeria. During this period, 47 out of the 49 dental consultants/examiners who participated in the examination were served the questionnaire (see the Attachment). Thirty-four (34) of them filled and returned the questionnaire, giving initial response rate of 72.34%. Additional 14 respondents (consultants who could not be reached to fill the questionnaire at Ibadan and some that did not participate as examiners at Ibadan) were reached online using the Google forms through their personal social (WhatsApp) platforms. They all filled and returned the questionnaire online.The final sample (49 consultants) was drawn from the following eleven (11) training centres in West Africa: University College Hospital (UCH), Ibadan, Nigeria, Lagos University Teaching Hospital (LUTH), Lagos, Nigeria, ObafemiAwolowo University Teaching Hospital (OAUTH), Ile-Ife, Nigeria,University of Benin Teaching Hospital (UBTH), Benin City, Nigeria, University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital (UNTH), Enugu, Nigeria, University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital (UPTH), Port Harcourt, Nigeria, University of Calabar Teaching Hospital (UCTH), Calabar, Nigeria, Amino Kano Teaching Hospital (AKTH), Kano, Nigeria, Usman Danfodio Teaching Hospital (UDTH), Sokoto, Nigeria, Teaching Hospital Conakry, Guinea, and Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital, Ghana.

2.3. Objectives of the Study

- 1. To determine the level of awareness of the PBS among dental consultants in the region2. To determine the knowledge of PBS among the dental consultants3. To determine the attitude of the dental consultants towards the PBS

2.4. The Null Hypotheses

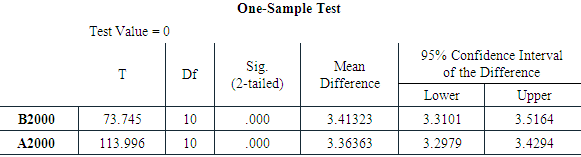

- The following null hypotheses were generated and tested:There would be a significantly poor general awareness of the Phantom Bite Syndrome among the dental trainers and teachers (dental consultants) in the West African sub-region, including the knowledge of the first author of Phantom Bite Syndrome (Ho1).There would be significantly poor general knowledge of the symptoms of Phantom bite syndrome among the dental consultants (Ho2).There would be no significant difference in the knowledge of the symptoms of Phantom bite syndrome between those who graduated from the dental school before and after the year 2000 (Ho3).There would be no positive attitude among these specialists towards increasing the awareness and knowledge of Phantom bite syndrome in the region (Ho4).

2.5. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

2.5.1. Inclusion Criteria

- 1. Only dental consultants, that is, dental professionals who have postgraduate qualifications of either the West African College of Surgeons or that of the National Postgraduate College of Nigeria and are registered as specialists by the Medical and Dental Council of Nigeria (MDCN) in any dental specialty, and are involved in the teaching and training of undergraduate and/or postgraduate dental resident dental surgeons.2. Such a dental consultant could be an examiner or yet to be one in the postgraduate examinations of either the Dental Faculties of the West African College of Surgeons or the National Postgraduate Medical College of Nigeria or both.

2.5.2. Exclusion Criterion

- Any dental professional who is yet to obtain any postgraduate qualifications and as such not registered by the Medical and Dental Council of Nigeria (MDCN) as a dental specialist.

2.6. Weighting or Scoring of the Questionnaire Options

- Every Correct Answer received 5 scores; ‘Do not know’ option had 3 scores, while each Wrong Answer got 2 scores.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

- The Statistical Package for Social Sciences (IBM SPSS) version 25 was used to analyze the data. In addition to the descriptive statistics used, the Chi-square test and One-sample T-test were employed in the analysis as appropriate. The significance level was set at P < 0.05.

3. Results

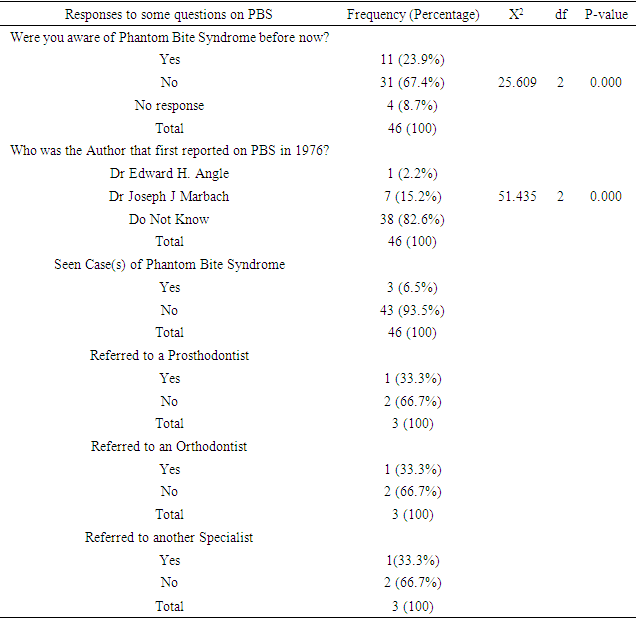

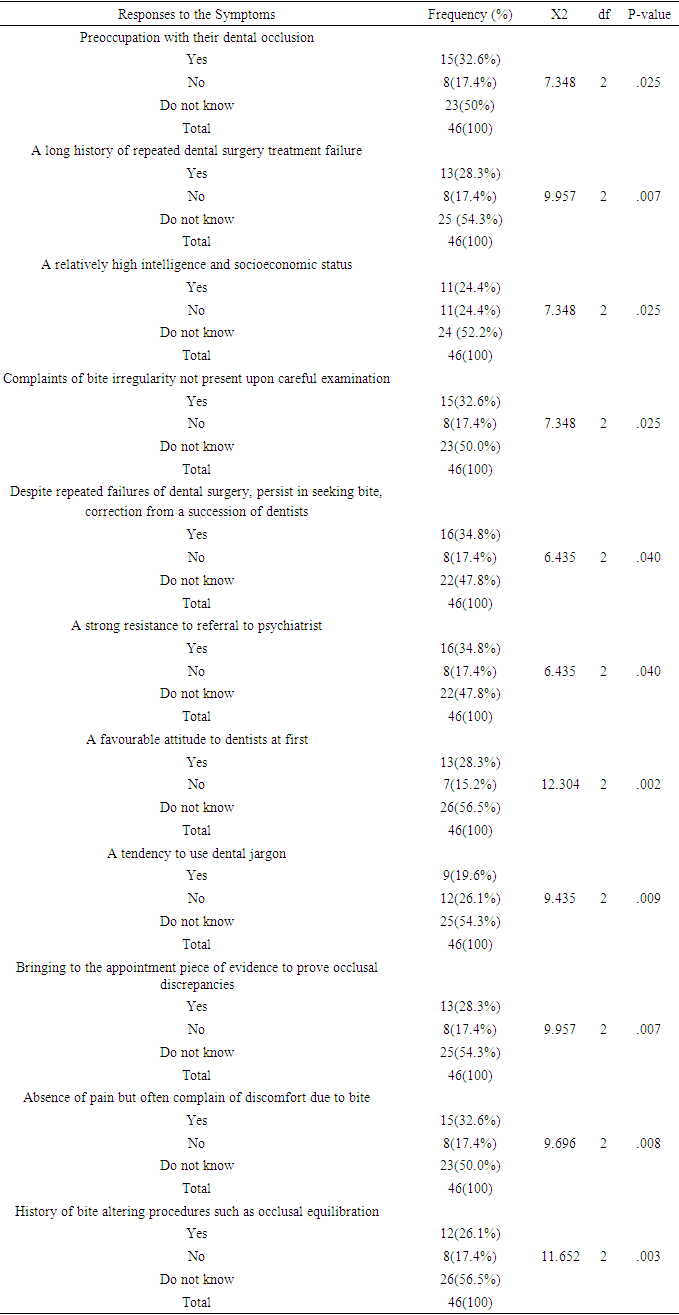

- A total of forty-six (46) participants were recruited into the study consisting of 29 (63%) males and 17 (37%) females with the age range of 40 to 72 years (mean age of 53.20 ± 8.13). The percentage distribution of the participants (Dental Consultants) based on the specialty are as follows: 15(32.61%) Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons, 10(21.74%) specialists in Conservative Dentistry and Prosthodontists, 7(15.22%) Oral Pathologists and Oral Medicine specialists, 7(15.22%) Periodontologists, 4(8.69%) Paedodontists and 3 (6.52%) specialists in Community Dentistry.Table 1 below provides the responses of the participants to some of the questions on Phantom Bite Syndrome, with a highly significant number of the participants not being aware of the syndrome before this study (P = 0.000), as well as not knowing the author who first reported on this syndrome in 1976 (P = 0.000). In addition, only 3(6.5%) claimed they had seen at least a case of the syndrome before this study. The first null hypothesis is hereby accepted.

|

|

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

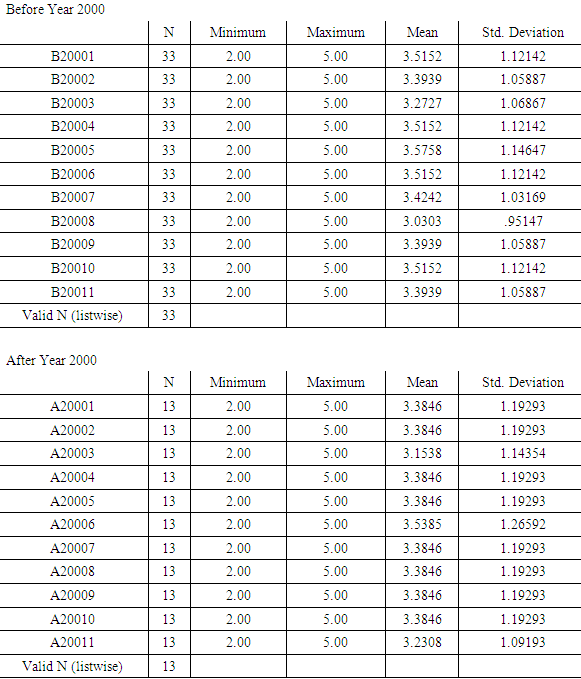

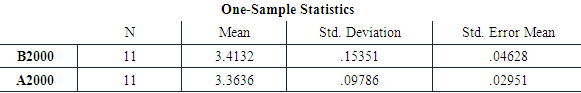

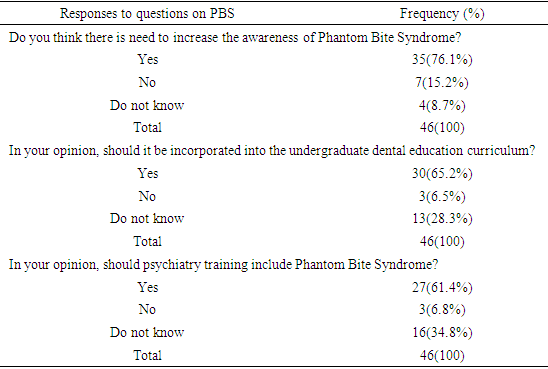

- This first ever study from Nigeria and possibly from Africa on Phantom Bite Syndrome (PBS) has clearly shown that there is a significant poor awareness of this syndrome among dental consultants studied including the knowledge of the author who first reported on this syndrome in 1976 [1]. In addition, this study has shown significantly poor knowledge of the symptoms of the condition among the dental specialists (dental consultants), as well as significantly no difference in their knowledge based on the period of graduation from the dental school. Also, this study has revealed generally positive attitude towards increasing knowledge of PBS in the sub-region by the participants.In a relatively recent publication by Tu et al [4], the critical role of enhancing dental professionals’ awareness of this phenomenon was emphasized for the successful management of such patients. The very significant poor awareness of this phenomenon revealed in this Nigerian study is an affirmation of the rationale or importance of this study. Although the syndrome is rare, the serious consequences on such patient’s quality of life, personal relationships that could lead to financial loss, career disruption or even suicidal thoughts makes it so crucial that dental consultants must be aware of it and pass across the necessary information to their students and trainees. Also, this will help them to be ready to take the right decisions concerning such patients when they are seen. In addition, the generally noted significantly poor knowledge of the symptoms of the phenomenon among the studied dental consultants means a serious justification of this study to fill up the knowledge gap. Comparatively, even the fact that their poor knowledge of the symptoms of this condition between those who graduated from dental schoolsbefore the year 2000 (older graduates) and those who graduated after the year 2000 (relatively recent graduates from our dental schools) was found to be significantly the same means that there is need for a change of the narrative among the dental professionals.It must be noted that a good number of the consultants graduated from the older dental schools in Nigeria established in the 1970s. The year 2000 was chosen as a separating year because the initial dental curricula of the dental schools have changed in recent years. It would seem to be a good guide to know if the earlier curricula of our dental schools gave some exposure to the older consultants on PBS or vice versa. Therefore, this study has shown that there was nothing like that from the results of the knowledge of the two groups of dental graduates analyzed in this study. Accordingly, the participants showed generally positive attitude towards the PBS as they mostly indicated interest in increasing awareness of this phenomenon, would want its teaching incorporated in the dental undergraduate curriculum, as well as supporting that it should be part the curriculum in psychiatry education in our medical schools. This finding is encouraging and consistent with most recent publications [3-6,8-19]. According Kelleher and Canavan [5], the psychiatric hypothesis has been challenged and alternative explanations have been proposed with the postulations that the condition might be an intraoral sensory disorder that can occur spontaneously; or in conjunction with an underlying autoimmune disorder; or with trigeminal neuropathic pain. Much earlier in 2003, Clark and Simmons [18] in proposing their theory of altered oral kinesthetic ability as another possible mechanism of PBS did not invalidate Marbach’s theory of diagnosable psychiatric disorders but rather agreed with Green and Gelb [19], stating that although patients’ symptom and behaviours have certain psychological impact, the main underlying cause would be the unknown alterations in proprioceptive input transmission. Although there is improved understanding of this condition presently, it remains a real challenge for clinicians to recognise the symptoms and provide appropriate psychological therapy, psychiatric medications and possible neurological treatment. Since PBS patients mainly complain of occlusal discomfort and rarely present severe psychiatric comorbidities (depression, anxiety disorder, insomnia, somatic symptom disorders), they seldom are provided active psychiatric treatment [4]. Therefore, dental surgeons must avoid unwarranted repeated occlusal treatments or adjustments often requested by the patients. The findings of this study have indeed adequately met the objectives. The Strengths and Limitation of this StudyAlthough not every dental trainer or examiner in West African region responded to this questionnaire, the representative nature of the study sample for the study population is a major strength of this work. Therefore, the findings of this study could be seen as a fare reflection of the knowledge and attitude of the target population towards the subject matter, and their views about incorporating the subject into dental curriculum could be taken seriously. In addition, the questions in the questionnaire concerning the symptoms of PBS resulted from the consistent findings of different studies [4,5,6,8,9,13-19] on this subject. However, it must be noted that the study is limited by the fact that the questionnaire was not subjected to validity testing through face or content validity prior to distribution of the questionnaire.

5. Conclusions

- 1. This study has revealed a significantly poor general awareness of the Phantom Bite Syndrome among the dental trainers and teachers (dental consultants) in the West African sub-region, including the knowledge of the first author of Phantom Bite Syndrome.2. Significantly poor general knowledge of the symptoms of Phantom bite syndrome among the dental consultants has been shown.3. No significant difference in the knowledge of the symptoms of Phantom bite syndrome between those who graduated from the dental school before and after the year 2000, that is, between older and younger consultants.4. Significant positive attitude among these specialists towards increasing the awareness and knowledge of Phantom bite syndrome in the region was observed.

6. Recommendations

- Based on the findings of this first Nigerian study on the PBS and all available literature on this subject, the following are recommended:• Dental consultants, who are the teachers and trainers in our Universities and Teaching Hospitals, should ensure that lectures on PBS are incorporated in the undergraduate curricula of our dental schools and postgraduate dental training programmes.• Considering the current views on pathophysiology of the condition, other dental consultants must work closely with the oral medicine specialists/orthodontists and the psychiatrists to ensure that such a patient when diagnosed receives the best care in this part of the world.• The dental consultants should go further to equip themselves with the details of management of such a patient as indicated in the cited literature, while increasing vigilance for such patients in our environment.

Attachment

- QUESTIONNAIRE ON PHANTOM BITE SYNDROMEPlease, your help as you freely participate in this study is highly appreciated. This is purely for research purposes only and your responses will be confidently handled accordingly. Thanks a lot for providing your honest responses in this questionnaire. God bless you richly.SECTION A1. Age ------- 2. Gender --------3. Name of Hospital where you work: ------------------------4. Profession: Dental Surgeon ----------------------------- 5. Year of undergraduate graduation: ------------ 6. Consultant / Specialist in -------------------------------7. How long have you been practising Dentistry? ----------------------------SECTION BWhere you aware of Phantom bite syndrome before now? Yes ------- No ----------Which of these researchers (authors) reported Phantom bite first in 1976? (a) Dr Edward H. Angle ------ (b) Dr Joseph J. Marbach ------(c) Clark et al -------- (d) Jagger and Korszun -------------- (e) Do not know ----------------------------- Have you ever seen any case(s) of Phantom bite syndrome before? Yes ----- No ------If Yes, how did you manage it?Referred to a Prosthodontist? Yes --------- No ----------------Referred to another Orthodontist? Yes ------------- No ------------Referred for psychological evaluation? Yes --------- No -----------Referred to another Specialist? Yes ----------- No -------------------Sent back to the referring doctor? Yes --------- No ------------------Started orthodontic treatment? Yes ----------- No -------------------Mounted models, did occlusal analyses, gave orthodontic treatment Yes ---- No ---Referred to the Dental Practitioners Yes ------- No --------------Others (please specify) ----------------------------------------------------------------------Do you know the symptoms of Phantom bite syndrome? Yes ------- No -----------Which of these is/are part of the symptoms of Phantom bite syndrome?Preoccupation with their dental occlusion and an enormous belief that their dental occlusion was abnormal: Yes ---------------- No. --------- Do not know -------------A long history of repeated dental surgery treatment failures with persistent requests for the occlusal treatment that they are convinced they need: Yes -------- No --------- Do not know ------------------A relatively high intelligence and socioeconomic status enabled them to undergo endless costly and time consuming dental treatments: Yes --- No ---- Do not know -------Complaints of bite irregularity not present upon careful examination: Yes -- No ---Do not know ------------Despite repeated failures of dental surgery, persist in seeking bite correction from a succession of dentists: Yes ---------- No --------- Do not know ----------------A strong resistance to referral to psychiatrists and stick to dental procedures: Yes --------- No ----------- Do not know --------------A favourable attitude to dentists at first, gradually blaming them for the exacerbated symptoms, finally dropping out with disappointment: Yes --------- No --------- Do not know -----------A tendency to use dental jargon: Yes ----------- No -------- Do not know -----------Bringing to the appointment pieces of evidence to prove occlusal discrepancies (radiographs, study cast, temporary crowns, mouthpieces, etc.): Yes ----- No –--- Do not know ----------Absence of pain but often complaints of discomfort due to bite: Yes -- --No –--- Do not know --------History of bite-altering procedures such as occlusal equilibration, multiple restorations or repeated orthodontic treatments: Yes ---- No ---- Do not know ------a. In your opinion, do you think there is need to increase awareness of Phantom bite syndrome in Nigerian orthodontic/dental/ psychiatric practice? Yes ------ No ------- Do not know --------------------------------b. In your view, should undergraduate dental education curriculum include Phantom bite syndrome? Yes ---------------- No --------------------- Do not know -------------------c. In your view, should Psychiatry training include Phantom bite syndrome? Yes ----- No --------- Bo not know ------------------- THE END

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML