-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2023; 13(5): 559-568

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20231305.04

Received: Mar. 28, 2023; Accepted: Apr. 14, 2023; Published: May 12, 2023

Iraqi Experts’ Consensus on Diagnosis and Management of Functional Constipation in Infants and Children

Razzaq Jameel Altuwaynee1, Hassan Al-Timimi2, Ahmed Shemran Alwataify3, Alaa Jumaah Nasrawi4, Amal Adnan Rasheed5, Mohammed Enghadh Attallah6, Rasim Mohammed Khamass7, Mohammed Hussein Assi8, Abdul Hadi Aljuraisy9, Ziad Bassil10, Hayder Fakhir Mohammad11

1Department of Pediatrics, University of Thi-Qar, College of Medicine, Nasiriyah, Iraq

2Department of Pediatrics, Child and Birth Hospital, Misan, Iraq

3Department of Pediatrics, Babylon Hospital for Children and Maternity, University of Babylon, Babylon, Iraq

4Department of Pediatrics, College of Medicine, University of Kufa, Kufa, Iraq

5Department of Pediatrics, Azadi Teaching Hospital, Kirkuk, Iraq

6Department of Pediatrics, Al-Ramadi Teaching Hospital for Maternity and Children, Ramadi, Iraq

7Department of Pediatrics Nephrology, Al-Karama Teaching Hospital, Baghdad, Iraq

8Al-Mustansiriya University, College of Medicine, Baghdad, Iraq

9Department of Pediatrics, Ibn Bildy Teaching Hospital, Baghdad, Iraq

10Department of Pediatrics and Neonatology, Saint Joseph Hospital, Beirut, Lebanon

11Department of Pediatrics, College of Medicine, University of Sulaymaniyah, Sulaymaniyah City, Kurdistan Region, Iraq

Correspondence to: Hayder Fakhir Mohammad, Department of Pediatrics, College of Medicine, University of Sulaymaniyah, Sulaymaniyah City, Kurdistan Region, Iraq.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

In light of the current situation of poor medical practice in Iraq, we urgently need to update our clinical practice guidelines and unify our diagnostic criteria for pediatric functional constipation (FC). In addition, functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) in general have been on an increasing trend in the last few years, especially in the middle-east region. Therefore, we aim to offer children with FC the best management for their constipation, update pediatricians/primary care physicians (PCPs) knowledge in GIDs in general, and establish guidelines for all Iraqi and regional pediatricians/PCPs for the management of FC. Ten pediatric consultants attended two advisory board meetings to discuss and address the current challenges, provide solutions, and reach an Iraqi national consensus for the management of pediatric FC. Experts Meetings resulted in 24 consensus statements that serve as recommendations for clinical practice. Our recommendations cover clinical approach, diagnostic criteria, predisposing factors, health-related outcomes, and management plan (including non-pharmacological and pharmacological treatment options).

Keywords: Functional constipation, Infantile constipation, Constipation, Functional gastrointestinal disorders, Iraq, Consensus, Formula

Cite this paper: Razzaq Jameel Altuwaynee, Hassan Al-Timimi, Ahmed Shemran Alwataify, Alaa Jumaah Nasrawi, Amal Adnan Rasheed, Mohammed Enghadh Attallah, Rasim Mohammed Khamass, Mohammed Hussein Assi, Abdul Hadi Aljuraisy, Ziad Bassil, Hayder Fakhir Mohammad, Iraqi Experts’ Consensus on Diagnosis and Management of Functional Constipation in Infants and Children, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 13 No. 5, 2023, pp. 559-568. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20231305.04.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Non-specific gastrointestinal symptoms such as constipation, diarrhea, colic, and recurrent vomiting showed a high prevalence among infants and children, especially in countries of the Arabian Gulf region [1]. Gastrointestinal disorders (GIDs) are classified based on their etiology into organic and functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs). Their defined etiology recognizes organic GIDs as Crohn's disease or celiac disease. On the contrary, FGIDs include a wide range of GI symptoms that cannot be attributed to any apparent organic cause after the appropriate medical examination and investigations [2]. Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and functional constipation (FC) are the most common FGIDs in general, while regurgitation, colic, dyschezia, and FC are the most frequent FGIDs occurring during infancy [3,4]. Vague and non-specific symptoms usually manifest in infants and children suffering from FGIDs; therefore, their diagnosis is a challenging process. The diagnostic approach of infants/children with FGIDs is based on the full history including the onset of symptoms, course of the disease, duration, severity, aggravating or relieving factors, previous history of the same condition, and any family history of the same condition. That is why investigations have a very limited indication in the diagnosis of FGIDs. However, they are used to rule out OGIDs. The diagnostic approach of FGIDs is mainly established by the application of Rome IV criteria [5]. Constipation is categorized into several types – based on the etiology – including functional (non-organic), anatomic, abnormal intestinal motility (due to intestinal nerve abnormality), drug-related (iatrogenic), metabolic (such as hypokalemia or hypercalcemia), and hormone-related constipation (endocrinal) [6]. Epidemiological data from the literature suggest that FC is accounted for 90-95% of all cases of infantile constipation globally [7-9]. FC showed fluctuating incidence rates in many previous studies, ranging from 9.6% among European infants/toddlers to 31.4% among African children [10-12]. Iraq is the 4th largest Arabic country in population, with 37% of its population under 14 years. However, there is a scarcity of published epidemiologic data, clinical characteristics, and management approaches of FGIDs in Iraq [13]. Most of the FGIDs manifested during infancy stop around the age of 1 year, unlike FC, which is manifested throughout different age groups. For instance, an infant’s colic discontinues at the age of 4-5 months, dyschezia stops at the age of 8-9 months, and regurgitation stops at 12 months [14]. FGIDs are managed by different therapeutic options including milk formulas, pharmacological treatment, behavioral therapy, and complementary therapeutic approaches [15]. However, the availability of these multiple treatment options for FGIDs does not eliminate the need for more effective treatment in order to encounter their increasing worldwide prevalence. This consensus is developed in order to reach an Iraqi national consensus for practical considerations and clinical implications of pediatric FC. Our objectives from these experts’ recommendations include helping children to have the best management for their constipation, updating pediatricians/primary care physicians (PCPs) knowledge in gastrointestinal disorders in general, and establishing guidelines for all Iraqi and regional pediatricians/PCPs for the management of pediatric FC. This manuscript is intended to provide solutions for the current challenges regarding the prevalence and management of FC among Iraqi infants and children. Also, we highlighted the current status of FGIDs in general in Iraq from the clinical perspectives of the participating experts.

2. Consensus Development

- To address the current challenges, provide solutions, and reach a national consensus for the management of constipation in Iraqi infants and children, an advisory board meeting was held virtually on May 2021. Ten Pediatric experts (from different regions of Iraq) shared their opinions through the Delphi method of communication to develop the current Iraqi consensus. Each expert was invited to be part of this panel group and to participate in this meeting to share his opinions and expertise through rounds of anonymous electronic voting with group discussion, correction, and modification of statements [16]. The second round of voting was conducted after the open discussion between the experts’ panel members. All members of the experts’ panel have extensive clinical experience in the management of FGIDs among infants and children. Also, most of the panel group have previous research experience or publications in infants’ gastrointestinal disorders. The voting process was conducted in two separate stages. After finishing the first stage of individual voting, a virtual meeting was held to modify each statement according to participants’ comments and recommendations. Then, the 2nd round of voting was conducted to reach a final consensus on all of the proposed statements. All experts agreed to consider the statement validation if they reached more than 80% agreement.

3. Results

- The panel experts’ group developed 24 statements for the initial round of voting. Of these 24 statements, 12 have entered the second round of voting after group discussion and re-evaluation. These two rounds resulted in 24 statements proceeding to the final approval, and only one statement did not reach a consensus and was excluded. The final approved statements are presented below alongside their corresponding recommendations.

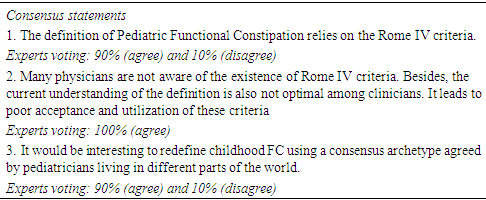

3.1. Rome IV Criteria

- FGIDs are highly prevailing among infants and toddlers around the world. They comprise a wide range of GI disorders manifested by recurrent, chronic, and non-specific symptoms that cannot be related to any physical or biochemical aberration [2]. Rome IV criteria is the gold standard diagnostic tool used for FGIDs diagnosis worldwide. The last version of Rome IV diagnostic criteria for FC in infants and children (up to 4 years) stated that in order to diagnose FC in an infant/child, the patient should manifest at least two of the following symptoms for more than one month: (1) two or fewer defecations/week, (2) history of excessive stool retention, (3) history of painful or hard bowel movements, (4) history of large diameter stool, and (5) presence of a large fecal mass in the rectum [17]. These criteria are mainly applied to the non-toilet trained children, while in the toilet trained children, they added another two criteria: (6) presence of at least one episode of incontinence/week and (7) history of large diameter stool that may obstruct the toilet [17]. The items of Rome IV criteria can be applied from birth till adolescence (including neonates, infants, toddlers, and adolescents).Although the Rome IV is a global diagnostic tool for FC in infants and children, yet many Iraqi pediatricians and PCPs are not aware of its application. Reports showed that Iraqi physicians do not usually follow the clinical practice guidelines in their practice [18]. The experts of the panel group endorsed the use of Rome IV criteria in FC diagnosis and highlighted that the current application of Rome IV criteria is not optimal among Iraqi clinicians, which will result in poor acceptance and utilization of these criteria.

3.2. The Diagnostic Approach for Infants and Children with Functional Constipation

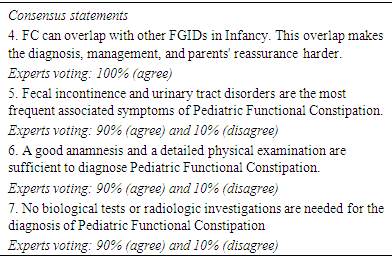

- Diagnosis of FC is a diagnosis of exclusion (i.e., exclusion of the presence of any organic cause). The diagnostic approach of FC begins with full detailed history (including diet and bowel habits) and a complete physical examination. The alarming signs (Red flags) must be checked carefully by the physician before reaching the diagnosis of FC as they indicate the presence of underlying pathology (organic cause). These red flags include the inability of the newborn to pass meconium in the first 24 hours after delivery, abdominal distention, bilious vomiting, failure to thrive, presence of bloody or mucoid stool, delayed neurological development, anal or sacral abnormalities, and presence of any other signs of other organic causes (such as fever or urinary tract infections) [9,19]. Multiple FGIDs share the same pathophysiological mechanisms; therefore, patients may present with a combination of FGIDs [20]. For example, Bellaiche et al. reported that most infants (25-50%) present with a combination of symptoms of FGIDs such as constipation, regurgitation, colic, and gas/bloating [12]. Such symptomatic overlapping will make the diagnostic track and parents’ reassurance more challenging. Fecal incontinence and urinary tract disorders are the most frequent associated symptoms with pediatric FC [21-23]. A large systematic review conducted by Summeren et al. reported that bladder and lower urinary tract symptoms are very common among children with FC [24]. The reported prevalence varied considerably among the included studies, ranging from 2% to 47% for single bladder symptoms, 37% to 64% for lower urinary tract symptoms, and 6% to 53% for urinary tract infections [24]. Fecal incontinence is considered a key symptom of pediatric constipation [25]. In a cross-sectional study conducted in Sri Lanka, authors reported the presence of constipation among 81.8% (N= 45) of children who suffered from fecal incontinence [26]. They also noticed a higher prevalence of fecal incontinence among children exposed to recent stressful events (such as family-related events or school bullying). Children with fecal incontinence and FC reported lower health-related quality of life (HR-QOL) scores than children with constipation alone [27]. The pediatrician or PCP should examine every infant or child presented with constipation and search for the presence of any alarming signs. The infant or child examination should start by looking for any anatomic abnormalities or any anal/sacral abnormalities. Then, the physician should proceed to the complete physical examination to exclude failure to thrive and the presence of any anatomic gastrointestinal problems suggested by abdominal distension or vomiting. The experts' group members stated that good history and detailed physical examination are sufficient tools to diagnose pediatric FC. They added that biological tests and radiological investigations are not indicated for the diagnosis of FC. However, they are used to exclude the suspicion of organic causes.

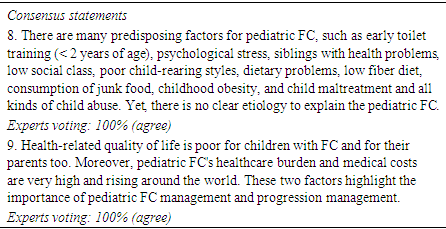

3.3. Predisposing Factors and Health-related Outcomes of Functional Constipation

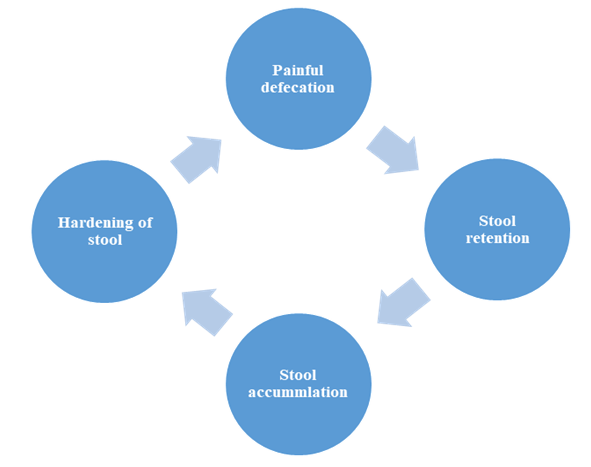

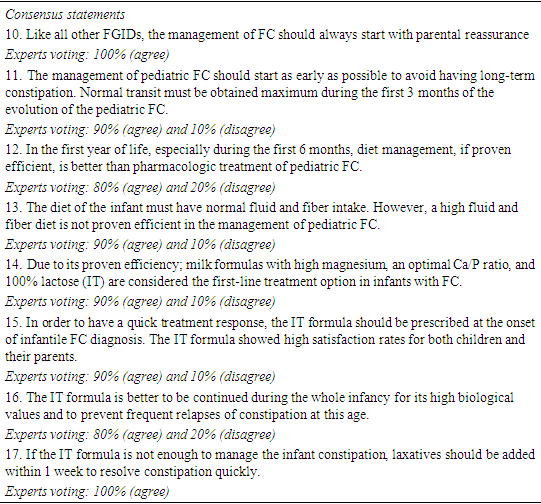

- The vicious cycle of FC pathophysiology is initiated by a sense of painful defecation that may result in stool withholding. This stool withholding state will eventually form a hard stool that will lead to a more painful defecation “Figure 1” [28]. Therefore, identifying the predisposing factors that start this cycle is a crucial step to prevent the development of FC. In a cross-sectional survey conducted in Korea to study the risk factors for FC in young children, authors revealed that children with a maternal history of constipation and a history of painful defecation before age 1 year have a higher risk of developing FC [29]. Also, a higher risk of FC was reported among children with a history of painful defecation during toilet training or sedentary activities of more than 2 hours /day [29]. Moreover, children with some dietary habits such as no meat consumption and intake of less than 500 ml water/day showed a higher risk of developing FC [29]. Children with stressful life events and psychological troubles tended to develop FC and suffered from more constipation episodes than other children [26,30,31]. Discrepancies have been projected in the literature on early toilet training and the risk of constipation. In a cohort study by Heron et al., authors reported a non-significant association between the age of toilet training, breastfeeding, birth weight, and the risk of constipation in children at school age (4-10 years) [32]. On the other hand, Hodges et al. showed that starting toilet training early (< 2 years) carries a higher risk of developing dysfunctional voiding and constipation [33]. Therefore, expert panel members recommend against toilet training in children younger than 2 years.

| Figure 1. The vicious cycle of functional constipation pathophysiology |

3.4. Management of Infants/Children with Functional Constipation

3.4.1. Non-Pharmacological Treatment Options

- Management strategy for infants and children with FC comprises non-pharmacological and pharmacological interventions. Non-pharmacological therapy comprises parental reassurance, education, diet management, and milk formulas [39]. North America Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition (NASPGHAN) and European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) 2014 guidelines for the management of infants/children with FC stated that; normal fiber intake, sufficient fluid intake, and regular physical activity are considered first-line non-pharmacological treatment options in infants/children with constipation [7]. Parental reassurance and education were proposed in the literature as an initial step in the management strategy for all cases of pediatric FC [7,40]. Parental education should include general information related to FC such as its prevalence, clinical presentation (symptoms), predisposing and risk factors, possible complications, available therapeutic options, and disease prognosis [39]. This information is sufficient to change the public concepts that might interfere with the management strategy [41]. Both parental reassurance and education showed high efficacy in the treatment of mild cases [40,41]. Dietary measures are another recommended treatment option to be started in infants with FC in their first year of life – especially in the first 6 months. Opposite to the common practice, instructing patients with constipation to increase their fluid and fiber intake is not recommended [7]. As per Ziegenhagen et al. and Chung et al., increasing the fluid intake in constipated patients produced no effects on stool consistency and resulted only in increasing the urine output [42,43]. Also, another study conducted in the USA reported no improvement in stool consistency or frequency in constipated patients had been noted with a 50% increase in fluid intake [44]. Adequate fiber intake is another recommended dietary measure to decrease the risk of constipation [45]. Cocoa Husk – a dietary rich fiber – has reduced the intestinal transit > 50 percentile in constipated children compared to placebo [46]. Dietary measures are preferable over pharmacological treatment to avoid adverse drug events (AEs), especially in the first 6 months of life. A key step in the management of pediatric FC is an early and adequate therapeutic intervention. The early management protects the constipated infant/child from developing long-term constipation. Milk formulas that contain high Magnesium have been reported to increase stool frequency and decrease stool consistency, i.e., formation of loose stool and improve defecation pain than other comparators [47]. Other than being effective, Mg-rich formula is also safe, increases the level of parents’ satisfaction, and improves the QOL of both parents and infants. These promising results, alongside the high parents’ satisfaction, resulted in the desire of almost all parents to adhere to the Mg-rich formula after one month of formula intake [47]. The ideal calcium: phosphorus (Ca/P) ratio is that of breast milk [48]. A body of evidence found that the Ca/P ratio less than the breast milk ratio increases the risk of constipation [48]. For instance, cow’s milk – which has a Ca/P ratio of 1.2:1 – is a possible risk factor for infants to develop hard stool. Novalac Mg-enriched formula [improved transit (IT)] is a magnesium-enriched formula that has proved its efficacy in pediatric constipation. The Novalac formula reduced stool consistency, increased stool frequency, and increased stool weight compared to the strengthened regular formula [49]. A recent study conducted in the Middle-East region reported the same results regarding the Novalac Mg-enriched formula and reported a significant improvement in stool characteristics in the Mg-rich formula’s (Novalac formula) group compared to the control group (Similac Comfort) [47]. Experts’ panel members recommend using the IT formula at the onset of diagnosis of infantile FC to obtain the best treatment outcomes. For its high biological values, good health outcomes, and to decrease the risk of relapses, experts also recommend continuing on the Mg-enrich formula (IT formula) during the whole infancy period. To get the best clinical outcomes, laxatives are advised to be added to the IT formula if the formula fails to achieve the complete symptomatic resolution.

3.4.2. Pharmacological Treatment Options

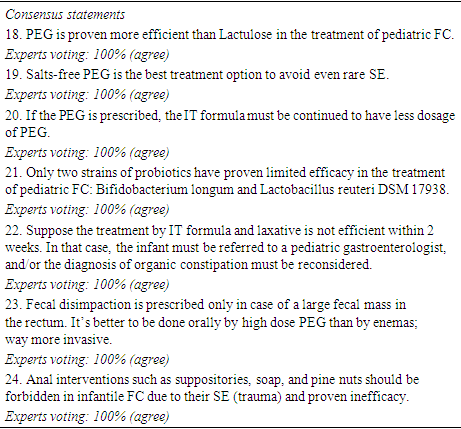

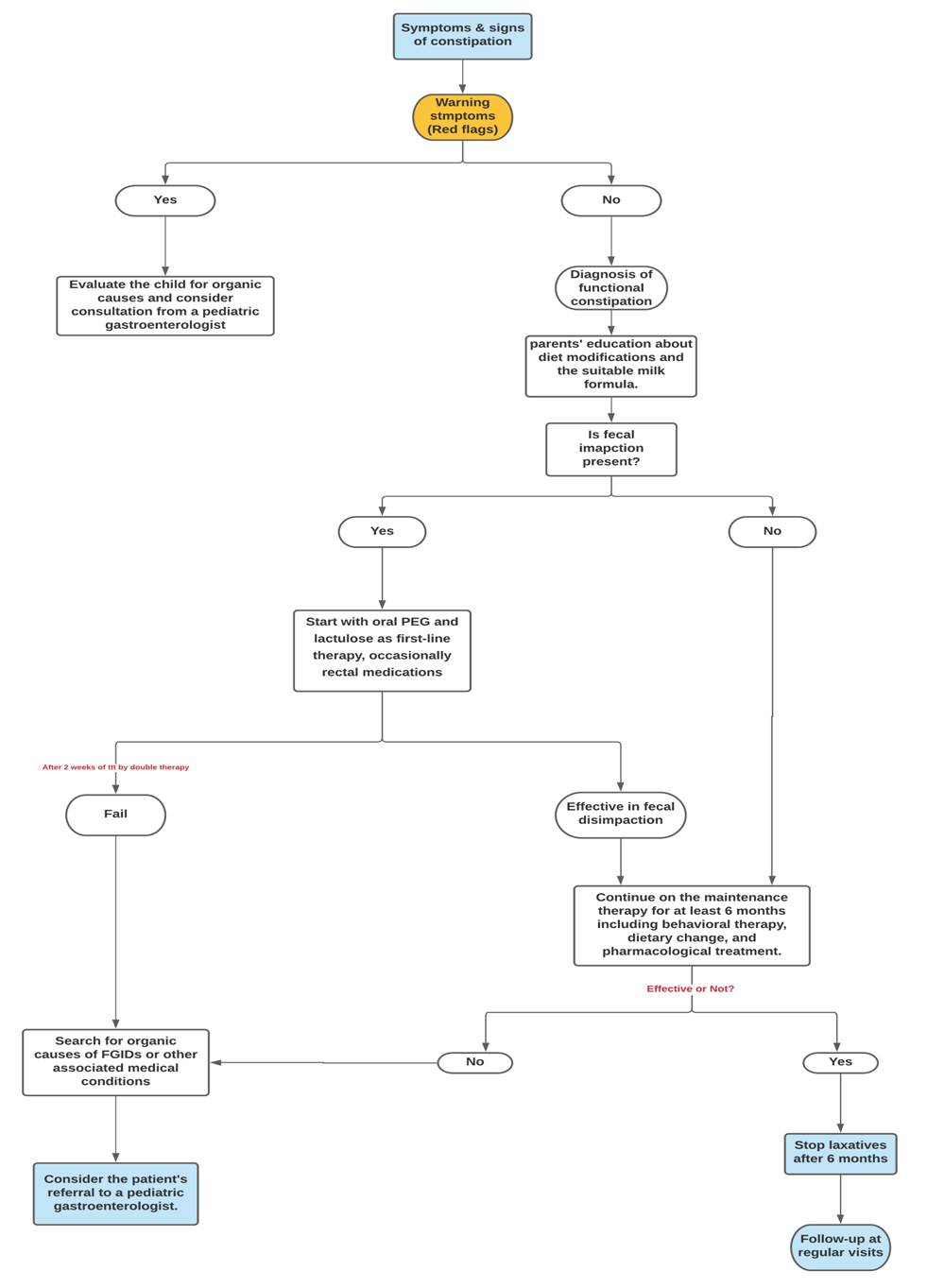

- According to their reported efficacy and safety profile, new treatments have replaced the old ones as a first-line pharmacological treatment for pediatric FC in recent years. For example, lactulose – one of the most commonly used laxative drugs – has been replaced by polyethylene glycol (PEG) as a first-line treatment option in cases of fecal disimpaction due to the high frequency of side effects (SE) associated with lactulose use. PEG displayed higher clinical outcomes in stool disimpaction rate and stool frequency among constipated infants compared to lactulose [50]. On the other hand, lactulose use in the treatment of pediatric constipation has experienced an acute decline in the last years due to its reported SE such as nausea, vomiting, flatulence, abdominal pain, and bloating as a result of gas production [51]. In terms of patients’ safety, salt-free PEG (PEG 3350 solution) is an osmotic laxative that carries no risk of electrolyte imbalance and hence no/minimal risk of SE [52]. In a prospective, double-blind, parallel study by Youssef et al., higher doses of PEG 3350 daily for 3 days showed a high level of patients satisfaction alongside a high disimpaction rate among constipated children compared to the lower doses [53]. Treatment with probiotics and prebiotics is another treatment option for pediatric FC that has been discussed in the literature. Probiotics are living microorganisms (mostly bacteria) found in certain food or supplements, while prebiotics are non-digested carbohydrate fibers that serve as a nutrient for gastrointestinal microbiota [54]. If administered in an adequate amount, they can improve the health status of the human body [55]. Seven core probiotic strains are mostly used in therapeutic products; however, only two probiotic strains (Bifidobacterium longum and Lactobacillus reuteri DSM 17938) have been tested in clinical trials and showed limited efficacy in the treatment of pediatric FC [56-58]. In a systematic review by Tabbers et al. [59], the authors included two trials that studied the effectiveness of probiotics or prebiotics in the treatment of pediatric FC. According to their GRADE evaluation, the quality of the present evidence is very limited to support the routine use of prebiotics or probiotics in the treatment of pediatric constipation. These findings align with ESPGHAN and NASPGHAN clinical practice recommendations for prebiotics and probiotics use in childhood constipation [7]. Experts agreed that constipated infants/children who are not responding to a dual therapy by IT formula and laxative should be referred to a pediatric gastroenterologist for consultation and reevaluation. As per ESPGHAN and NASPGHAN clinical practice guidelines, if the dual therapy (i.e., IT formula and laxative) for 2 weeks is not effective, the diagnosis of organic causes of FGIDs must be reconsidered [7]. Untreated or chronic cases of constipation are usually complicated by fecal impaction. Fecal impaction occurs when a large fecal mass gets stuck in the colon and obstructs the colonic movement. In a randomized clinical trial by Bekkali et al, authors studied the efficacy and safety of rectal enemas versus high doses of oral PEG in the treatment of rectal fecal impaction in children [60]. Both PEG and rectal enemas have shown a successful disimpaction rate (68% and 80%, respectively). Authors also recommend that PEG and rectal enemas should be considered first-line therapeutic options in cases of fecal impaction [60]. The panel group experts agreed by consensus that anal interventions such as suppositories, soap, and pine nuts should be avoided in infantile FC due to their SE related to trauma and their proven inefficacy. “Figure 2” displays our recommended management algorithm for pediatric FC.

| Figure 2. Management algorithm of pediatric functional constipation |

4. Conclusions

- The diagnosed cases of FGIDs in infants/children have increased significantly in the last few years in Iraq. Many infants/children presented to the clinic complaining of combined symptoms of FGIDs. The diagnosis of pediatric FC is a diagnosis of exclusion, meaning that we have to exclude the presence of any alarming symptoms or signs before reaching the diagnosis of FC. The diagnostic approach of FGIDs is mainly established through the application of Rome IV criteria (the gold standard diagnostic tool). Diagnostic investigations such as biological or radiological investigations are not needed to diagnose a case of FC – except in limited indications to exclude organic causes – that is why the items of Rome IV criteria are entirely clinical symptoms. The clinical practice in Iraq is mainly experience-based, as most Iraqi physicians are not aware of the application of Rome IV criteria. Therefore, it would be interesting to redefine childhood FC using a consensus archetype agreed by pediatricians living in different parts of the world. Management of childhood FC mainly depends on the stage of clinical presentation and the presence of any alarming signs. Initially, the child must be evaluated for the presence of any organic causes of childhood constipation if the child is showing any alarming symptoms/signs. First-line non-pharmacological treatment options (including parental education, diet modifications, and milk formula) should be considered in all cases with pediatric FC, and they are usually sufficient to manage early non-complicated cases. While, pharmacological treatment options (including oral PEG, lactulose, or occasionally rectal medications) should be started in late cases complicated with fecal impaction. Our management recommendations are intended to be used nationally by all Iraqi pediatricians and PCPs.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- Consensus panel experts would like to thank Novalac, MENA region for their technical support, providing the required approvals for such a national meeting to occur. In addition, all members of the experts’ group appreciate the efforts exerted by RAY-CRO in drafting and writing the consensus statements. Dr. Ahmed Salah Hussein – an employee of RAY-CRO, Egypt – compiled the authors' comments and supported the writing of this manuscript.

Disclosure

- Conflict of interest All authors declare no conflict of interests. Each author has revised and approved the final version of the manuscript independently. Authors’ contributions All authors contributed equally in drafting or revising the manuscript for intellectual content and published evidence. Each author approved the final version of the manuscript.Financial support This consensus was conducted under the sponsorship of Novalac, Middle-East and North Africa (MENA) region, which did not intervene in the design, voting process, writing, interpretation, preparation, and drafting of this document for publication.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML