-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2023; 13(3): 271-275

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20231303.16

Received: Feb. 6, 2023; Accepted: Mar. 6, 2023; Published: Mar. 15, 2023

Our Experience with the Use of Regional Anesthesia in the Treatment of Multiple Atherosclerotic Lesions of the Carotid Arteries in Patients with Coronary Heart Disease

Shavkat Karimov1, Akmal Irnazarov2, Abdurasul Yulbarisov1, Hojiakbar Alidjanov1, Doniyor Nurmatov1, Sarvar Abduraxmonov1

1Republican Specialized Center of Surgical Angioneurology, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

2Tashkent Medical Academy, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Introduction: Anesthesia for carotid endarterectomy (CEA), general or regional, has been an issue of debate in literature. The aim of this study was to evaluate the influence of regional anesthesia on perioperative mortality and morbidity in patients with ischemic heart disease undergoing carotid surgery. Material and methods: This prospective study included 117 consecutive patients with co-excisting multiple atherosclerosis of carotid and coronary arteries operated under cervical plexus block. Results: Shunt placement rate was 3.3%, and all patients had a good outcome. The average carotid clamping time was 19 minutes. Pulmonary complications were not observed. There was 1 death (0.9%) due to myocardial infarction. Two patients (1.7%), both symptomatic, had a small ipsilateral ischemic stroke with good recovery. Conclusion: Carotid artery endarterectomy can be safely performed in the awake patient, with low morbidity and mortality rates.

Keywords: Anesthesia, Carotid surgery, Ischemic heart disease, Perioperative mortality, Coronary arteries, Cervical plexus block, Concomitant pathology, Atherosclerosis

Cite this paper: Shavkat Karimov, Akmal Irnazarov, Abdurasul Yulbarisov, Hojiakbar Alidjanov, Doniyor Nurmatov, Sarvar Abduraxmonov, Our Experience with the Use of Regional Anesthesia in the Treatment of Multiple Atherosclerotic Lesions of the Carotid Arteries in Patients with Coronary Heart Disease, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 13 No. 3, 2023, pp. 271-275. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20231303.16.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- One of the options for the surgical treatment of patients with atherosclerosis, in particular with a combined lesion of the carotid and coronary arteries, is the reconstruction of both vascular regions – simultaneous or staged carotid endarterectomy (CEA) and coronary artery bypass surgery. The choice of such a surgical strategy is due to the fact that combined lesion of the carotid and coronary arteries often leads to the occurrence of such complications as myocardial infarction (MI) after CEA and stroke after cardiac surgery [1-3]. As a result, the anesthesiologist faces the difficult task of ensuring the safety of the patient with impaired cerebral and cardiac circulation, and it is the anesthetic management that becomes the factor determining the outcome of the operation [4,5].Perhaps no other surgical intervention in modern anesthesiology is not associated with such a diametral divergence of opinions about the optimal method of anesthesia, as CEA. The main subject of discussion is the possibility of alternative use of either general or regional anesthesia.Objective: to study the results of carotid endarterectomy under regional anesthesia in patients with a multiple atherosclerotic lesion of carotid and coronary arteries.

2. Material and Methods

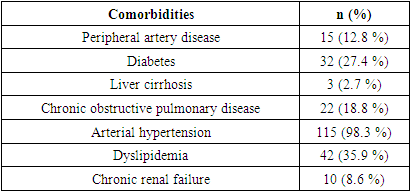

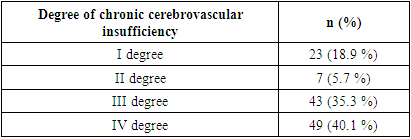

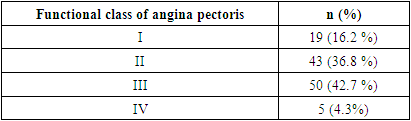

- From August 2020 to December 2021, 122 consecutive carotid endarterectomies were performed on 117 patients with co-excisting atherosclerosis of carotid and coronary arteries under loco-regional anesthesia at the Republic Specialized Center of Surgical Angioneurology and Department of Vascular Surgery, Tashkent Medical Academy, Uzbekistan. All patients were included in a prospective registry, and signed a written informed consent form before surgery. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Tashkent Medical Academy. Patients were between 41 and 93 years old, the average age of patients was 59±7.8 years. There were 90 male (73.8%) and 32 (26.2%) female patients. All patients had various comorbidies, such as diabetes, hypertension, peripheral artery disease, dyslipidemia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and chronic renal failure, which are listed in Table 1.

|

|

|

3. Results

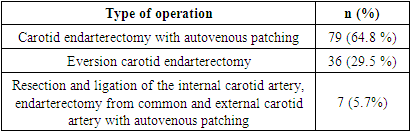

- The carotid endarterectomies were performed with loco-regional anesthesia in 117 patients undergoing 122 surgeries: no patient required conversion to general anesthesia. Types of operation are listed in Table 4.

|

4. Discussion

- Atherosclerosis is the disease of the century, both past and present. Atherosclerotic lesions of the carotid and coronary arteries are the leading cause of such a common catastrophe as stroke and myocardial infarction. Even for the USA with advanced medicine, where national programs for the prevention of atherosclerosis are implemented, the incidence of ischemic stroke is 1 per 100 population in terms of all age groups, and the ratio for the age group over 70 years is 10 times higher [1]. No other surgical intervention in modern anesthesiology is associated with such a diametral divergence of opinions about the optimal method of anesthesia, as CEA. The main subject of discussion is the possibility of alternative use of either general or regional anesthesia. The discussion about the optimal method of anesthesia continues today, and the arguments from both sides look quite convincing [9-11]. So as positive points of general anesthesia, her supporters indicate the following [12-14]: a) reliable control of the airway; b) the ability to control and manipulate the level of CO2 in the blood; c) the possibility of immediate pharmacological protection of the brain using barbiturates; d) overall comfort of the operation for the patient (and for the surgeon), regardless of the duration of the procedure. The disadvantages of the general anesthesia method are also well known and obvious [13,14]. These include: a) the difficulty of early diagnosis of cerebral ischemia at the stage of crossclamping, as well as some complications of the early postoperative period (early postoperative thrombosis, hyperperfusion syndrome); b) stress associated with tracheal intubation and extubation; c) significantly higher frequency of cardiovascular disorders in the perioperative period, such as acute myocardial infarction, arterial hypertension, severe cardiac rhythm disturbances, compared with regional anesthesia. Supporters of regional anesthesia bring its following benefits [15,16]: a) the highest level of neuro-monitoring in terms of informativeness and ease of implementation is dynamic neurological monitoring, which allows immediate diagnosis of developing cerebral ischemia at the stage of crossclamping and in early postoperative period. This also eliminates the use of expensive and time-consuming modalities of neuro-monitoring, thereby saving time and money. b) significantly lower frequency of using temporary inraarterial shunt. c) lower incidence of severe cardiovascular disorders in the perioperative period compared with general anesthesia. d) avoiding intubation and extubation of the trachea with their inherent stress. e) shorter stay of the patient, both in the intensive care unit and in the clinic as a whole. The disadvantages of regional anesthesia include the following points [17,18]: a) emotional discomfort experienced by the operated patients present at their operation. b) risk of so-called "mosaic blockade" or simply insufficient analgesia (significantly reduced when using a neurostimulator). c) possibility of respiratory depression, including due to the blockade of the phrenic nerve on the side of anesthesia. In addition, it should be remembered that regional anesthesia by itself does not have a cardio-protective effect on myocardial ischemia, but only reduces the number of stressful situations (for example, intubation and extubation of the trachea) [19]. The GALA (General Anesthesia vs Local Anesthesia) study is the largest randomized surgical and anesthesiological study, involving 3,526 patients treated in 95 centers in 24 countries. This bidirectional, in parallel groups, a multicenter randomized controlled trial was organized to determine whether the type of anesthesia affects perioperative overall mortality and mortality from stroke, the quality of life in the short term, and the absence of strokes and heart attacks during one year of observation. Analysis of the results has shown that neurological complications on the contralateral side in case of occlusion of the contralateral artery were more likely in the general anesthesia group (54% vs 29%). Thus, local anesthesia had an advantage in patients with contralateral occlusion. Observation during the year in the GALA study showed a slightly lower incidence of end-point detection in patients operated on under local anesthesia (p <0.094) [20]. It should be noted that the incidence of complications for groups with both general and local anesthesia was significantly lower than in NASCET and ECST studies, and this is evidence of a significant improvement in CEA results in recent years [20]. Despite a significant amount of researches, published in the literature, which analyzes the advantages and disadvantages of both approaches, including comparative studies, the conclusion about the advantages of one of the methods has not yet been made.

5. Conclusions

- The high risk of general anesthesia associated with concomitant and underlying diseases such as severe forms of coronary heart disease, chronic lung disease raises the necessary question of performing carotid endarterectomy under regional anesthesia in this category of patients. The use of regional anesthesia in carotid surgery in patients with multiple atherosclerotic lesion of the carotid and coronary arteries leads to a significant decrease in anesthetic risk, cerebral, pulmonary and cardiac complications.

Declaration of Interest

- The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

Funding Sources

- This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML