-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2023; 13(2): 165-169

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20231302.29

Received: Feb. 9, 2023; Accepted: Feb. 25, 2023; Published: Feb. 28, 2023

Choosing the Optimal Size for the Nephrostomy Tube after Standard Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy: A Randomized Trial

Sh. T. Mukhtarov1, 2, F. R. Nasirov1, 2, Y. U. Safaev1

1Republican Specialized Scientific and Practical Medical Center of Urology, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

2Tashkent Medical Academy, Department of Urology, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

Copyright © 2023 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

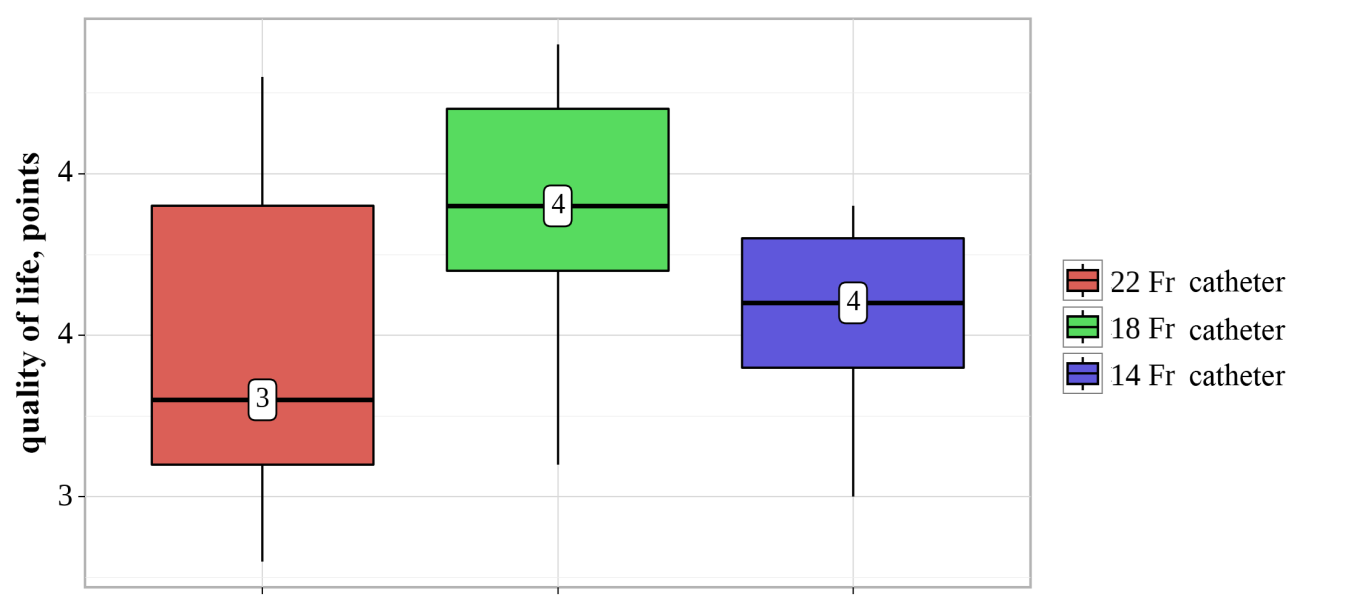

The aim of the study was an analysis and evaluation of the standard percutaneous nephrolithotomy results depending on the size of the nephrostomy tube. Background. Urolithiasis is the most frequent and recurrent urological disease. According to the literature, patients with this disease spend almost half (48.3%) of the bed-days of all urological diseases in the hospital. According to international guidelines on urology, percutaneous nephrolithotomy is the main method of surgical treatment for kidney stones larger than 2 cm. It is used for almost any size of stones located in the upper urinary tract, and this technique has proven to be less traumatic, less risky for the patient. Material and methods. This study includes the results of 300 procedures in patients with complex kidney stones performed in the period from 2020 to 2022. The patients were divided into 3 groups by randomization. Each group included 100 patients who were installed with a nephrostomy tube (22, 18 and 14 Fr, respectively,) after completion of standard percutaneous nephrolithotomy. In all cases access to the kidney was performed according to the Mannheim technique and surgical tubes 26 Fr were used. Results. The mean stone size in the groups was 34.1±11.6, 33.4±8.6 and 33.6±10.5, respectively. The surgery time in the groups was 66.7±15.4, 62.3±16.7 and 72.4±21.3 min, respectively. A statistically significant difference was observed between the results of group 2 and 3. The duration of hospital stay of patients in the groups was 3.9±1.2, 3.6±0.9 and 4.7±1.6 days, respectively. Conclusion. The presence of randomization ensured a relatively uniform distribution of patients into groups. The postoperative decrease of hemoglobin level was significantly less in Group I (22 Fr). Postoperative pain was the least (VAS=3.1) in patients with a smaller (14 Fr) drainage size.

Keywords: Urolithiasis, Percutaneous nephrolithotomy, Nephrostomy tube

Cite this paper: Sh. T. Mukhtarov, F. R. Nasirov, Y. U. Safaev, Choosing the Optimal Size for the Nephrostomy Tube after Standard Percutaneous Nephrolithotomy: A Randomized Trial, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 13 No. 2, 2023, pp. 165-169. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20231302.29.

1. Introduction

- Urolithiasis is the most frequent and recurrent urological disease. According to the literature, patients with this disease spend almost half (48.3%) of the bed-days of all urological diseases in the hospital [1]. There was a paradigm shift in the surgical treatment of urolithiasis with the invention of percutaneous nephrolithotomy (PNL). According to international guidelines on urology, PNL is the main method of surgical treatment for kidney stones larger than 2 cm. It is used for almost any size of stones located in the upper urinary tract, and this technique has proven to be less traumatic, less risky for the patient. Such treatment methods as extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) and retrograde intrarenal surgery (RIRS) can be considered for stones smaller than 2 cm [2,3].PNL has been developing since 1976 and has undergone many changes and improvements in methods and tools to maximize stone-free status with minimal complications. One of them is the miniaturization of tools. However, there is a huge proportion of complex kidney stones that require standard PNL. Standard PNL involves the use of percutaneous access to work with a tool size from 24 to 30 Fr and the installation of a nephrostomy tube after the surgery is completed [4].Despite the minimally invasive nature of the technique, it can cause significant pain in the postoperative period, and sometimes lead to life-threatening complications, such as bleeding from the kidney (wounds), sepsis and damage to surrounding organs [5]. The reported incidence of PNL-related bleeding ranges from 3.8% to 17.5% for patients who required a blood transfusion, and from 0.9% to 1.3% for those who require endovascular embolization [6]. The results of the surgery are influenced by many factors. They can be divided into two groups: factors that cannot be changed, and factors that can be influenced. The first group includes such factors as the size and location of the stone, the type of pelvicalyceal system, body mass index. The second group includes: the site of percutaneous access, the method of contact lithotripsy, the surgeon's experience and, of course, the type of nephrostomy tube that is installed at the end of the operation, and can potentially affect postoperative bleeding and pain [7]. There are enough publications data where the role of the surgeon's experience and the method of contact lithotripsy have been evaluated.The aim of the study was an analysis and evaluation of the standard percutaneous nephrolithotomy results depending on the size of the nephrostomy tube.

2. Material and Methods

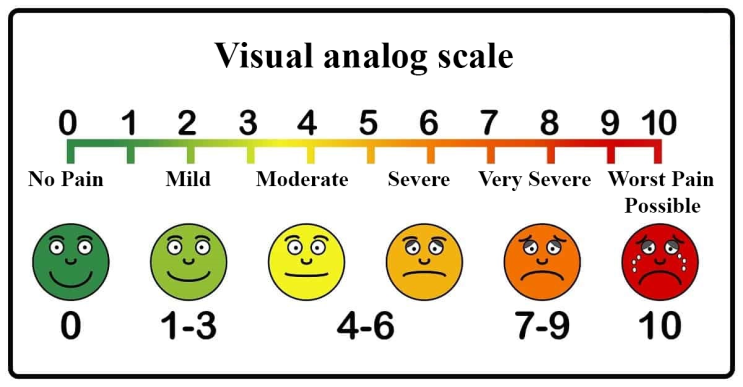

- This study includes the results of 300 procedures in patients with complex kidney stones performed at Republican specialized scientific and practical medical center of urology in the period from 2020 to 2022. The examination of the patients included the collection of anamnesis, physical examination, laboratory and radiological studies.The exclusion criteria were: secondary stones of the upper urinary tract, the absence of kidney function according to the urogram, the presence of perforation of the pelvicalyceal system, significant bleeding during surgery, and clinically significant residual stones after surgery.The patients were divided into 3 groups by randomization. The patients were divided into 3 groups by randomization. Each group included 100 patients who were installed with a nephrostomy tube (22, 18 and 14 Fr, respectively,) after completion of standard PNL. All surgeries were performed by surgeons with sufficient experience (more than 2000 percutaneous kidney surgeries). Procedures were performed under one of the anesthetic aids’ types (endotracheal anesthesia, spinal anesthesia) accepted in the clinic. The anesthetic risk of procedures was determined by the classification of the assessment of the objective status of the patient, adopted by the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA). In all cases access to the kidney was performed according to the Mannheim technique and surgical tubes 26 Fr were used. Pneumatic and ultrasonic methods were used to perform contact lithotripsy. Lithotripsy was conducted using a pneumatic and ultrasonic lithotripter of the company “EMS SA” Swiss Lithoclast (Switzerland). The duration of the surgical procedure was recorded from the beginning of access to the stone to the installation of a nephrostomy tube in the kidney. The postoperative decrease in blood hemoglobin compared to the initial value was evaluated between two groups on the 3rd day after surgery. Postoperative pain was evaluated using a visual analogue scale (VAS) 24 hours after the procedure. The adequacy of the nephrostomy tube function in the postoperative period was estimated by ultrasound examination. The standard course of the postoperative period corresponded to:- minor (not intensive) staining of urine with blood by nephrostoma which does not form blood clotting, does not violate its drainage function and does not require additional infusion (more than 1 liter), diuretic therapy and the prescription of hemostatics;- an increase in the patient's body temperature to 37.9°C without chills for no more than 48 hours, not requiring antipyretic and infusion therapy (more than 1 liter);- clinically insignificant residual stones.Statistical analysis was carried out using the IBM SPSS Statistics v 21 program. The comparison of two groups by a quantitative indicator, the distribution of which differed from the normal one, was performed using the Mann-Whitney U-test. Comparative differences were considered statistically significant with values of p <0.05.

3. Results

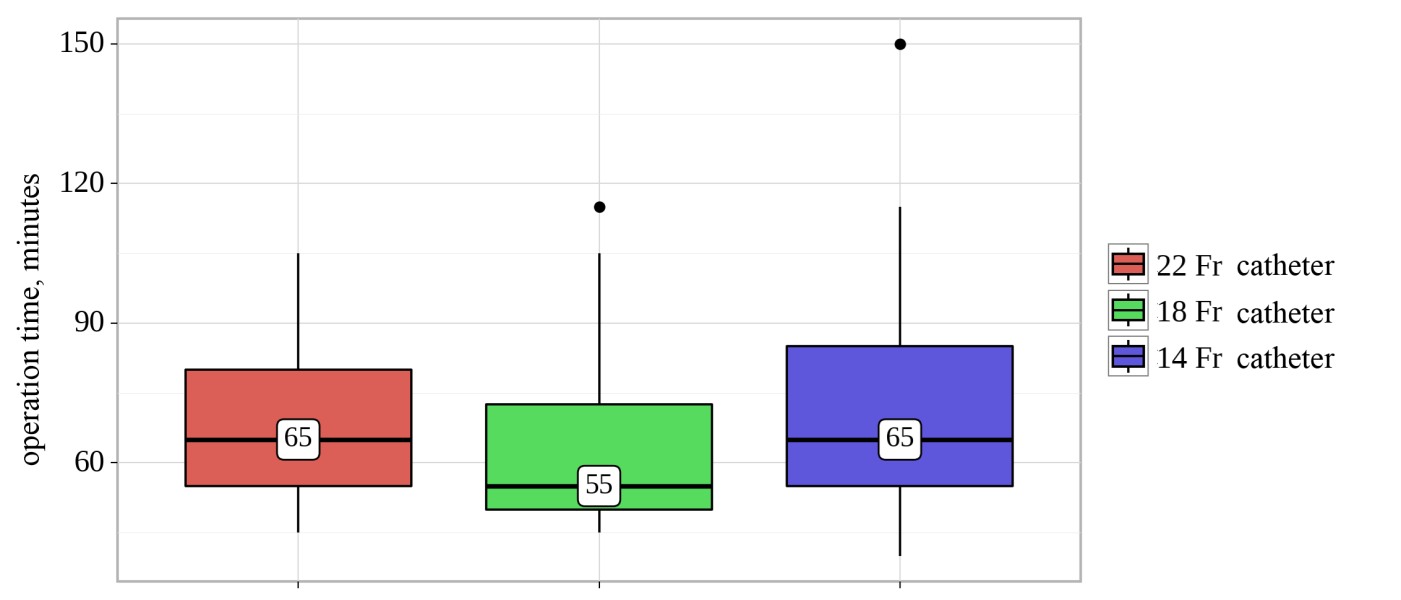

- The mean age of patients in Group I with 22 Fr catheters was 38.1 ± 14.9 years. In Group II (with 18 Fr catheters) and in Group III (with 14 Fr catheters) the mean age was 39.5 = 13.9 and 40.2 = 14.3 years, respectively.The mean stone size in the groups was 34.1±11.6 mm, 33.4±8.6 mm and 33.6±10.5 mm, respectively. The duration of surgery time in the groups made up 66.7±15.4 min, 62.3±16.7 min and 72.4±21.3 min, respectively. A statistically significant difference was observed between the results of group II and III (Fig.1).

| Figure 1. Surgery time indicators |

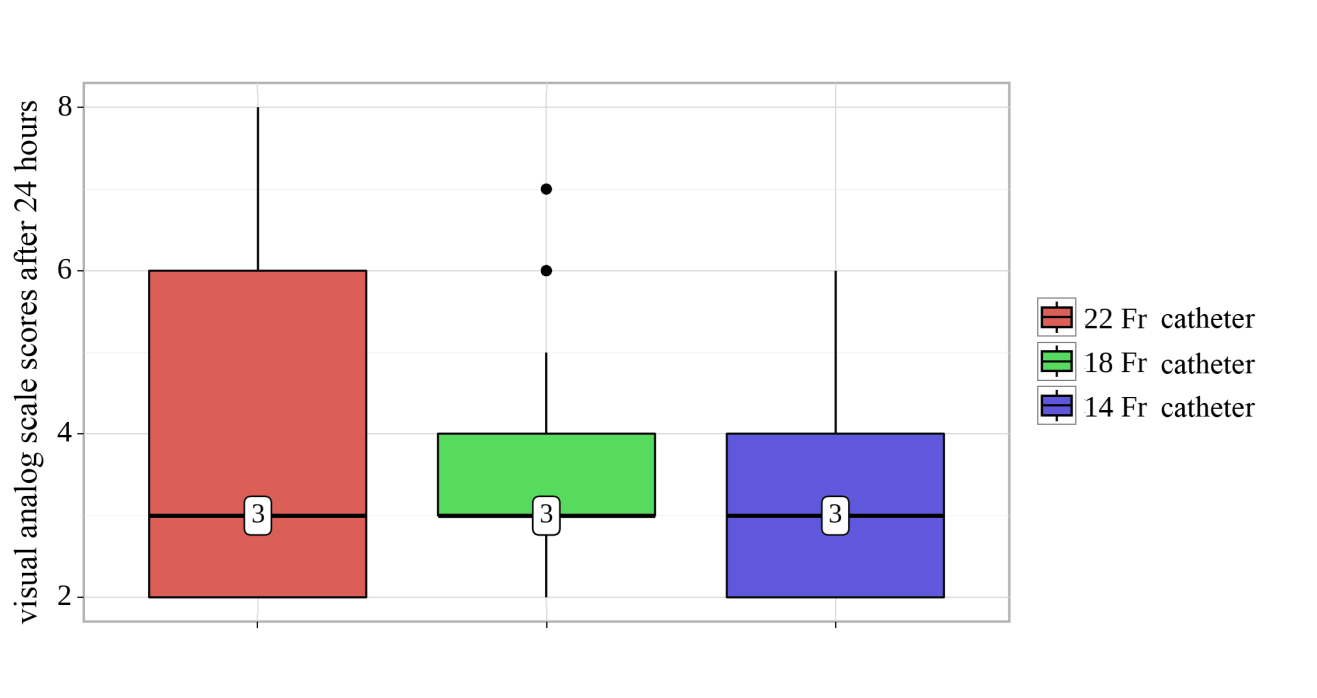

| Figure 2. Visual analogue scale (VAS) scores |

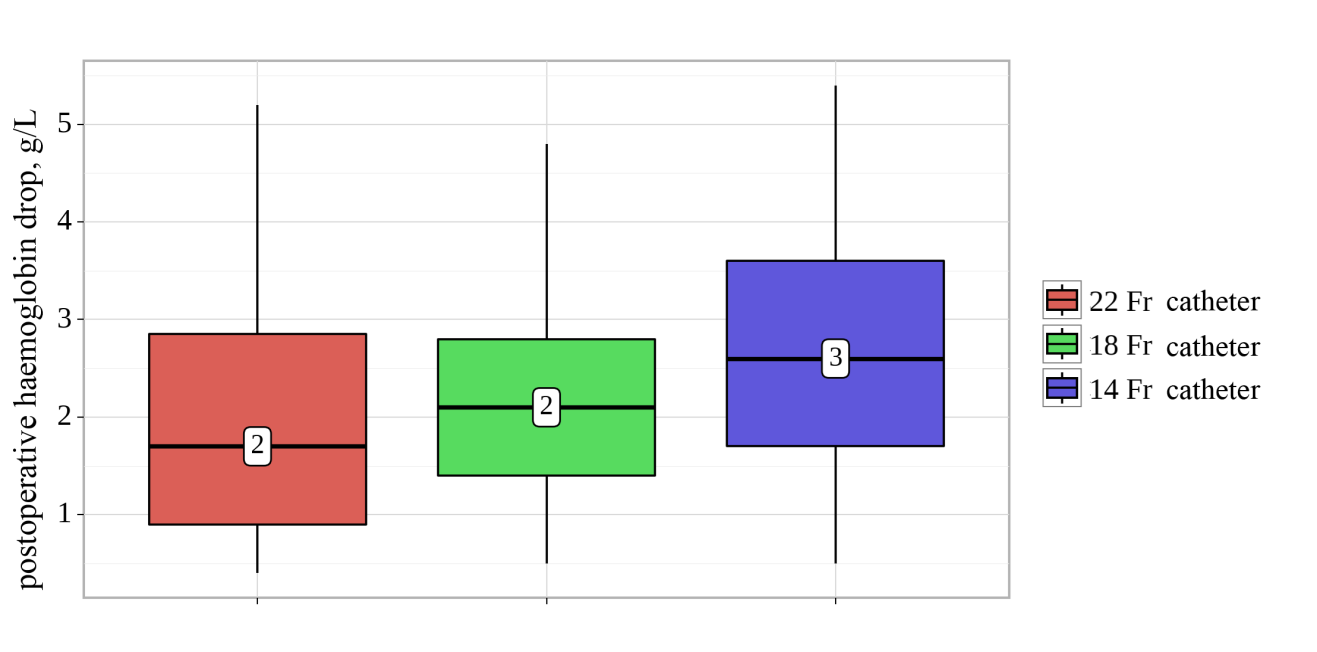

| Figure 3. Postoperative decrease of hemoglobin level |

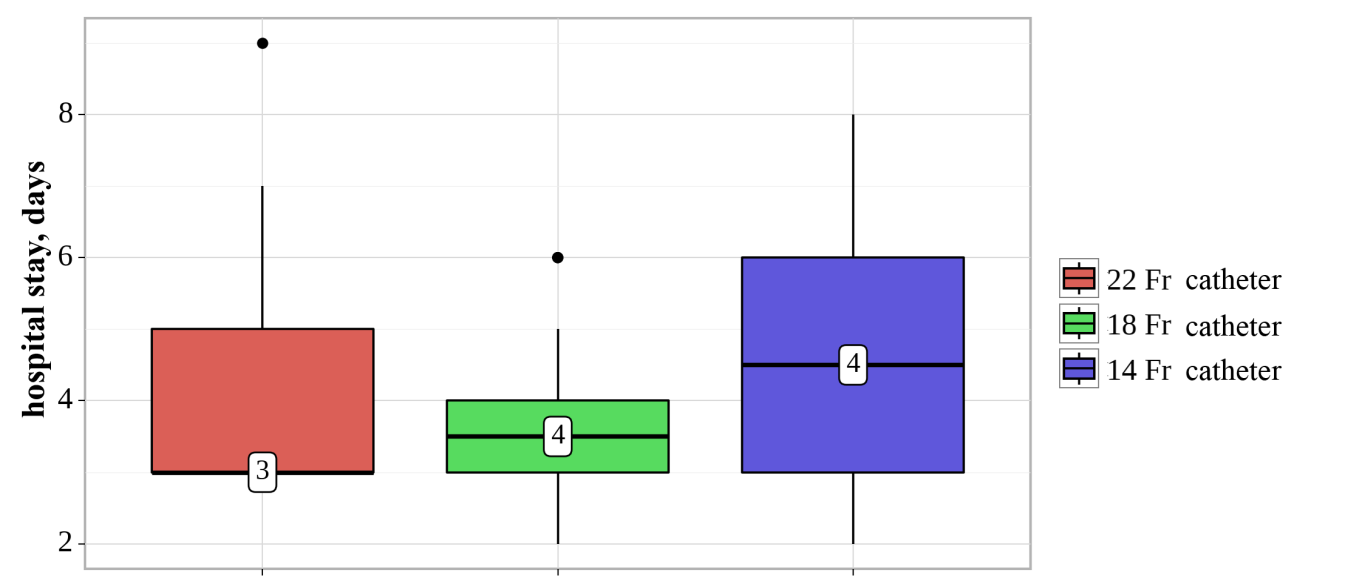

| Figure 4. The of duration of hospital stay |

| Figure 5. Life quality indicators |

4. Discussion

- The first published case of using a percutaneous drainage tube was recorded in 1943, when Davis DM installed a 14 Fr rubber catheter during an open ureterotomy. Subsequently, many new designs of tubes for percutaneous drainage were introduced, including Malecot, Foley and Councill catheters, etc. [8].In 2000 Maheshvari published the results of a study where 20 patients were performed 28 Fr nephrostomy tubes after standard PNL, and the remaining 20 were with 10 Fr nephrostomy tubes [9]. The authors note that the group with small tubes had significantly less analgesics consumed. The disadvantages of the study include the lack of randomization and pain assessment by means of a visual-analog scale (VAS) (Fig.6).

| Figure 6. An example of a visual-analog scale questionnaire |

5. Conclusions

- The presence of randomization ensured a relatively uniform distribution of patients into groups. The postoperative decrease of hemoglobin level was significantly less in Group I (22 Fr), which possibly associated with the hemostatic effect of a large catheter. Postoperative pain was the least (VAS=3.1) in patients with a smaller (14 Fr) drainage size. The hospital stay was also significantly longer in patients with a smaller (14 Fr) drainage size, which was due to a longer staining of urine through the tube in the postoperative period.The course of the postoperative period as a whole was significantly better in patients with nephrostomy drainage (14 Fr) in comparison with the groups of patients with drains 22 and 18 Fr, respectively.The authors declare no conflict of interest. This study does not include the involvement of any budgetary, grant or other funds. The article is published for the first time and is part of a scientific work.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML