-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2022; 12(5): 451-454

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20221205.01

Received: April 21, 2022; Accepted: May 8, 2022; Published: May 10, 2022

Estrogen (ER-α) and Progesterone (PR-α) Receptors Expression in Egg Endometriosis

Israilov Rajab Israilovich1, Juraeva Gulbakhor Baxshillaevna2

1Director of the Republican Pathological Anatomical Center, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

2Candidate of Medical Sciences, Head of the Department of Pathological Anatomy, Bukhara, Uzbekistan

Correspondence to: Juraeva Gulbakhor Baxshillaevna, Candidate of Medical Sciences, Head of the Department of Pathological Anatomy, Bukhara, Uzbekistan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2022 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This paper examines the degree of expression of estrogen (ER-α) and progesterone (PR-α) receptors in both glandular epithelium and stromal structures in ovarian endometriosis. As a material, ovarian tissue from 28 patients was immunohistochemically examined. Immunohistochemical examination of ovarian endometriosis revealed differences in the expression of estrogen (ER-α) and progesterone (PR-α) receptors in both epithelial cells and stromal structures. The sensitivity of these tissue structures to hormones during endometriosis, and the formation of specific protein receptors indicates the high rate of expression of the ER-α receptor relative to the PR-α receptor in epithelial cells that have become endometriotic glands relative to stroma structures indicates that the role of the hormone estrogen in the mechanism of endometriosis development is highly important.

Keywords: Ovary, Endometriosis, Immunohistochemistry, Estrogen, Progesterone, ER-a, PR-a receptors

Cite this paper: Israilov Rajab Israilovich, Juraeva Gulbakhor Baxshillaevna, Estrogen (ER-α) and Progesterone (PR-α) Receptors Expression in Egg Endometriosis, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 12 No. 5, 2022, pp. 451-454. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20221205.01.

1. Introduction

- In the study of endometriosis by morphological, histochemical, and immunohistochemical methods, it is important to know the histogenesis of the origin of the endometrial glands and epithelial glands of organs and tissues where endometriosis develops. After all, the metaplastic theory of the development of endometriosis plays a key role. The ovarian and Mueller tubes of the ovary arise from the selemic mesothelium, so the germinative epithelium of the ovary becomes the endometrial glands. However, because the mesothelium of the peritoneal serous membrane is a multipotent tissue, abdominal endometriosis develops from in-situ metaplasia of the mesothelium [1,2].In the study of the pathogenesis of endometriosis, Sampson advanced the theory of implantation. Because menstrual blood contains endometrial cells, they are implanted in the abdomen and other organs, proliferate, and lead to endometriosis. Hence, retrograde shortening of the fallopian tube causes retrograde menstruation and is a confirmation of the development of endometriosis in the fallopian tube and abdominal cavity [3,4,5]. It is estimated that the dissemination of endometrial cells through lymph and blood vessels causes extragenital forms of endometriosis.Sex hormones play a key role in the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Several clinical and experimental studies have confirmed that endometriosis is an estrogen-dependent disease. As evidence of this, endometriosis does not develop in girls until menopause begins. Endometriosis is often confirmed to develop due to high levels of estrogen, estrogenic obesity, and the artificial introduction of estrogen medication.Immunohistochemical examination detects protein-type receptors located on the surface of estrogen and progesterone-sensitive cells, i.e., antigen-specific antibodies. Because the epithelium of other organs and tissues outside the uterus originates from the selemic epithelium, receptors sensitive to specific estrogen and progesterone hormones appear, affecting them as the number of sex hormones in the body increases [3,4]. Detection of these receptors by antigen-antibody reaction in the immunohistochemical examination, their positive staining with a specially marked antibody confirms the presence of these receptors, the development of endometriosis. The results of this immunohistochemical method are evaluated by the following accepted terms: "strong positive reaction", "false positive reaction", "negative reaction" and "false negative reaction".

2. Materials and Methods

- As a material, a total of 28 patients with an average age of 28.5 ± 4.2 years who underwent surgery in the RPAС of the Republic of Uzbekistan biopsy diagnostics department in 2016-2021 underwent macroscopic examination of ovaries surgically removed with a diagnosis of endometriosis and incisions were made from areas where endometriosis-specific glands and cysts had grown. Biopsy sections were incubated for 48h in 10% neutralized formalin. Dehydration was carried out at increasing concentrations of alcohols and chloroform. Histological incisions were initially stained with hematoxylin and eosin to determine topography. Then a series of cuts from paraffin bricks were carried out in a specially automated system Ventana Benchmark XT, Roche, Switzerland, deparaffinization, dehydration, demasking, and staining in antigens. Receptors sensitive to estrogen (ER-α) and progesterone (PR-α) were identified using specially labeled antibodies. These receptors for weak, moderate, and strongly positively stained glandular epithelium and stromal cells were calculated by the following formula: HS = 1a + 2b + 3c, where a is the percentage of weakly stained cells, b is the percentage of moderately stained cells, and s is the percentage of strongly stained cells. The results were calculated on the following points: 0-10 points - no expression, 11 - 80 points - slow expression, 81 - 140 points - average expression, 141 - 300 points - strong expression. Statistical analysis of the obtained quantitative indicators is a practical statistical analysis program (Statistica Windows 10.0, SPSS Statistics 22, Microsoft Excel). In the groups, the performance of the characters was assessed using the Manna-Whitney test, and the statistical evaluation of the characters was performed at p≤0.05.

3. Results and Discussion

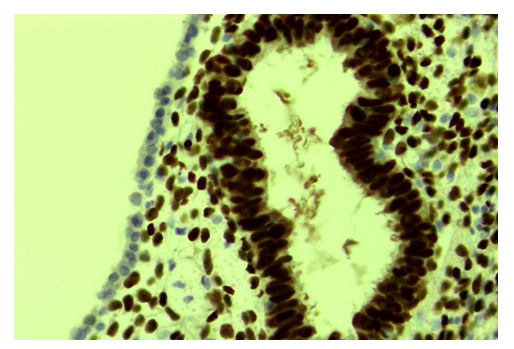

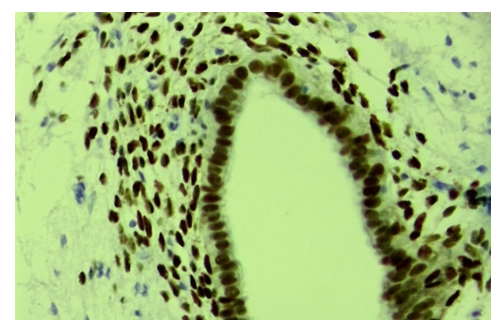

- The results of the study were determined as a percentage of slow, moderate, and high levels of estrogen (ER-α) and progesterone (PR-α) receptor expression. Estrogen (ER-α) receptor expression in the ovarian glandular epithelium was strong in 72.6% of 28 patients - an average of 286.4 points, 19.2% - 138.6 points, and 8.2% - 56.8 points. expressed. In cases of strong expression of the estrogen (ER-a) receptor, the epithelium of endometriotic gland structures growing under the outer mesothelium of the ovary is located in 2-3 rows, and both the cytoplasm and the nucleus of the ER-a receptor are strongly brown (Fig. 1). In the single-layered prismatic epithelium covering the outer surface of the ovary, it is observed that this receptor is almost not expressed. ER-α receptors are also relatively well expressed in the cells of the stroma-vascular structures around the gland.

| Figure 1. Strong expression of the ER-α receptor in ovarian endometriotic glands. Stain: immunohistochemical method. X400 |

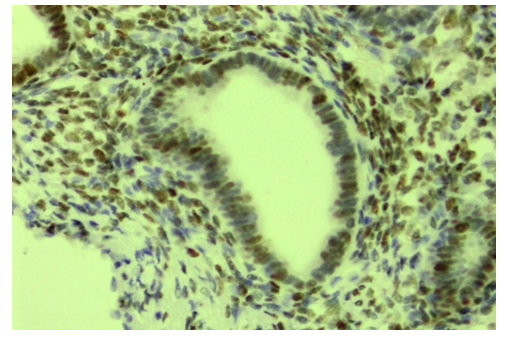

| Figure 2. Slow expression of the ER-α receptor in ovarian endometriosis glands. Stain: immunohistochemical method. X400 |

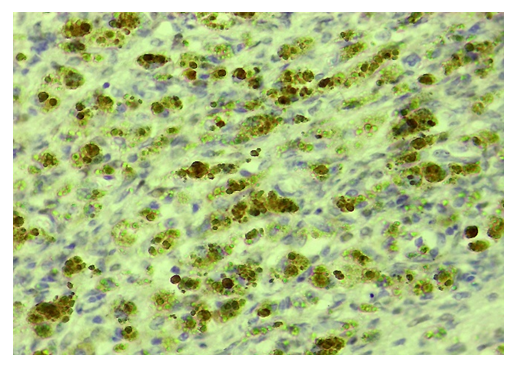

| Figure 3. Ovarian endometriosis, good expression of ER-α receptor in stroma cells. Stain: immunohistochemistry. X450 |

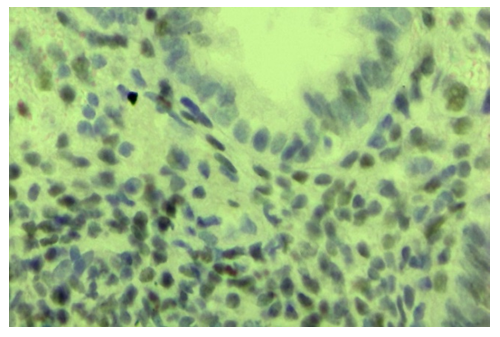

| Figure 4. Ovarian endometriosis, slow expression of the ER-α receptor in stroma cells. Stain: immunohistochemistry. X650 |

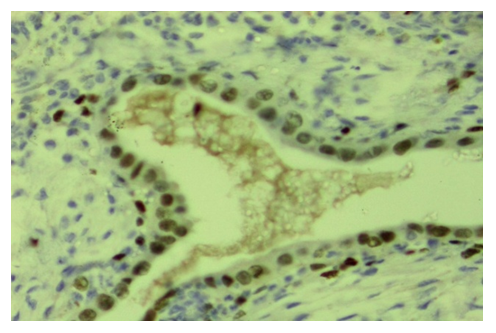

| Figure 5. Ovarian endometriosis, expression of progesterone (PR-a) receptors in both epithelial and stromal cells. Stain: immunohistochemistry. X400 |

| Figure 6. Ovarian endometriosis, expression of progesterone (PR-a) receptors in both epithelial and stromal cells. Stain: immunohistochemistry. X400 |

4. Conclusions

- Immunohistochemically examination of ovarian endometriosis revealed differences in the expression of estrogen (ER-α) and progesterone (PR-α) receptors in both epithelial cells and stromal structures. The sensitivity of these tissue structures to hormones during endometriosis, and the formation of specific protein receptors indicates the high rate of expression of the ER-α receptor relative to the PR-α receptor in epithelial cells that have become endometriosis glands relative to the stroma structures indicates that the role of the hormone estrogen in the mechanism of endometriosis development is highly important. A deeper study of the composition of these receptors at the level of molecular biology will help to determine what macromolecular reactions underlie the pathogenesis of endometriosis.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML