Z. M. Nizamkhodjaev, R. E. Ligai, R. R. Omonov, A. O. Tsoi, E. I. Nigmatullin, O. A. Fayzullaev, A. D. Abdukarimov, M. S. Koriev

Republican Specialized Center of Surgery Named after Acad. V.Vakhidov, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

Copyright © 2022 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Abstract

Aim of the research was to study the possibilities of minimally invasive endoscopic methods of treatment of patients with non-operable stages of esophageal cancer. Dysphagia is the most common clinical symptom of esophageal cancer; its consequence is often severe alimentary cachexia and poor quality of life. The average survival of patients with stage IV of esophageal cancer without treatment is less than 6 months. Reducing dysphagia is an important aim for this type of patients, but the volume of any intervention should be as small as possible and with minimal risk of postoperative complications. The article presents the treating experience of 464 patients with inoperable stages of esophageal cancer. The causes of inoperable behavior in this type of patients have been identified. 249 patients were performed various options of minimally invasive interventions: endoscopic tunneling, endoscopic bougienage and stenting. The installation of self-expanding metal stents is a safe, effective and fast treatment option for dysphagia relief in compare with other methods. A radioactive stent is preferred due to its greater efficiency in controlling dysphagia in patients with a longer life span.

Keywords:

Esophageal cancer, Minimally invasive treatment, Endoscopic tunneling, Endoscopic bougienage, Esophageal stenting

Cite this paper: Z. M. Nizamkhodjaev, R. E. Ligai, R. R. Omonov, A. O. Tsoi, E. I. Nigmatullin, O. A. Fayzullaev, A. D. Abdukarimov, M. S. Koriev, Stenting Results of Patinets with Esophageal Tumors Complicated by Dysphagia, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 12 No. 3, 2022, pp. 342-347. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20221203.24.

1. Introduction

The morbidity of esophageal cancer (EC) has increased over the past decades: takes the 7th place in the world and in many countries of Central and East Asia and the 19th - in Europe (UK - 6.6 per 100,000 people) [1-2].Low survival rates and poor prognosis are explained by the fact that half of patients deal with inoperable stages of tumors or they cannot undergo radical surgery consequently, there is a need for palliative, symptomatic treatment to overcome progressive dysphagia [3-4]. There are 3 categories of patients with esophageal cancer: patients suitable for surgery with a resectable tumor; non-operable patients due to non-operable tumor or metastases; patients with tumor recurrence [5]. Non-operable patients with locally advanced tumors or metastatic disease, as well as patients with tumor recurrence, require palliative care. Progressive dysphagia is present in more than 80% of these patients [6].Dysphagia is the most common clinical symptom of EC; its consequence is often severe alimentary cachexia and poor quality of life [7].The average survival of patients with stage IV of EC without treatment is less than 6 months. The goal of symptomatic, palliative therapy is to control the symptoms of the disease, to improve the quality of life and prolong survival as much as possible [8]. Reducing dysphagia is an important aim for this type of patients, but the volume of any intervention should be as small as possible and with minimal risk of postoperative complications.Various symptomatic treatment options for malignant dysphagia are available, including chemotherapy and / or radiation therapy, esophageal bougienage, diathermocoagulation, photodynamic therapy (PDT), brachytherapy and resection or bypass grafting, esophageal stents - all of these methods have their limitations [9].Options for controlling dysphagia and ensuring adequate nutrition in this case include self-expanding metal stents (SEMS) or gastrostomy (or jejunostomy) performed in a classical or minimally invasive way. Gastrostomy tubes do not relieve dysphagia, but may improve nutritional status [10].Clinical stage (cTNM), comorbidities, patient nutritional status, tumor characteristics, sufficient experience of surgeons, endoscopists and patient preferences are factors that determine treatment tactics.Aim of the research was to study the possibilities of minimally invasive endoscopic methods of treatment of patients with non-operable stages of esophageal cancer.

2. Material and Methods

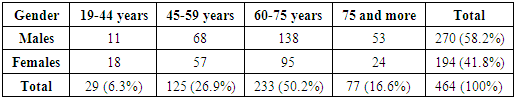

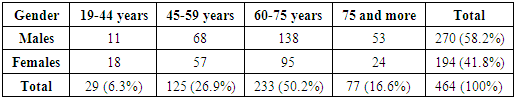

464 patients with non-operable stages of esophageal cancer were treated in the Department of the Esophagus and Stomach Surgery of the Republican Specialized Center of Surgery named after acad. V.Vakhidov for the period from 1996 to 2021. There were 270 males (58.2%) and 194 females (41.8%). The distribution of patients by gender and age is presented in Table 1.Table 1. The distribution of patients by gender and age

|

| |

|

The majority of patients were elderly and senile patients - 64.5%. However, taking into account the nature of the studied pathology, the fact of a rather high proportion of patients of young and mature working age deserves attention - 6.7% and 28.7%, respectively. The distribution of 464 patients with advanced stages by the duration of the disease showed that 111 (23.9%) were admitted within 3 months, 154 (33.2%) - from 3 to 6 months, 146 (31.5%) - from 6 months to 1 year and 53 (11.4%) patients - over 1 year.The main reason for the treatment of patients was dysphagia the degree of which, according to A.A. Chernyavsky (1991), was as follows: degree I – in 56 (12.1%) cases, degree II – in 321 (69,2%) patients, degree III – in 70 (15,1%) and degree IV – in 17 (3,7%) patients.The second most common complaint was weight loss: up to 5kg – in 167 (36%), up to 10 kg – in 149 (32.1%), up to 15kg – in 58 (12.5%), up to 2kgг – in 57 (12.3%) and over 20kg – in 33 (7.1%) patients. Thus, the majority of patients were admitted with symptoms of cancerous and alimentary cachexia.All patients were performed a comprehensive examination, which included endoscopy, polypositional X-ray contrast examination of the esophagus and stomach, ultrasound, computed tomography, MSCT and morphological examination of biopsies.The distribution of patients by anatomical localization of esophageal tumors was as follows: the cervical region - in 3 (0.7%), the upper third of the thoracic region - in 12 (2.6%), the upper and middle third of the thoracic region - in 26 (5.6%), the middle third of the thoracic region - in 151 (32.5%), the middle and lower third of the thoracic region - in 143 (30.8%), the lower third of the thoracic region - in 103 (22.2%) and the lower third of the thoracic region with extension to the cardioesophageal junction - in 26 (5.6%) patients. Thus, the majority of patients had intrathoracic lesions, especially in the middle and lower third.The length of the tumor process was evaluated endoscopically and by X-ray contrast study. The distribution of patients by length was as follows: up to 3 cm – in 33 (7,1%), 4-6 cm - in 149 (32.1%), 7-9 cm - in 143 (30.8%), 10-12 cm - in 81 (17.5%), over 12 cm - in 22 (4.7%) and in 35 (7.5%) cases it was not possible to accurately determine the length due to complete obstruction for barium suspension and water-soluble contrast.

3. Results and Discussion

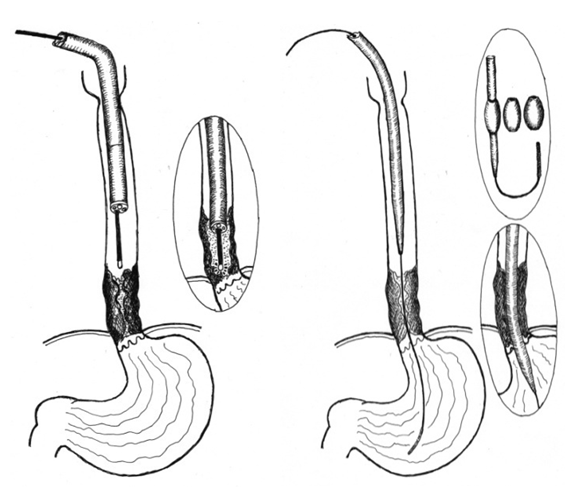

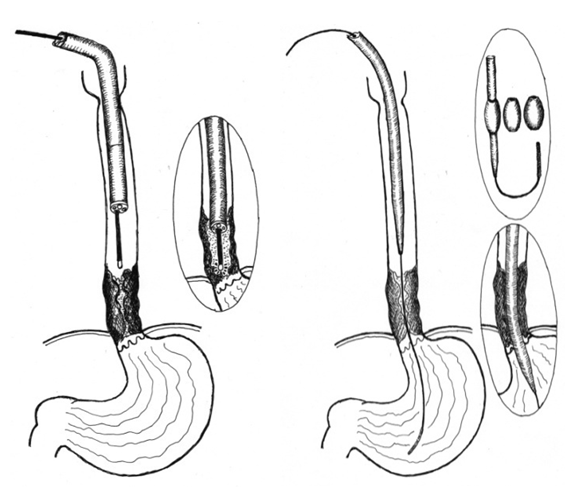

The treatment tactics depended on the condition of the patients and the results of a comprehensive examination on the basis of which 464 patients were conditionally divided into the following groups:Group I: 111 (23.9%) patients - no signs of inoperability were found according to the data of a comprehensive examination, however, 48 of them flatly refused surgery and other methods of treatment. Diagnostic interventions were performed in 61 patients (exploratory laparotomy (n=36) and thoracotomy (n=25)), in whom unresectability was revealed only intraoperatively: multiple liver metastases in 12, abdominal cancyromatosis (n=5), invasion into the aorta (n=15), in the lung parenchyma (n= 6), invasion into the main bronchi and the root of the lung (n=37), invasion into the trachea (n=9). Most patients had two or more complications of esophageal cancer.Group II: 353 (76.1%) patients in whom inoperability was determined at the stage of a comprehensive examination: the patient's age was over 75 years - in 67 (17.9%) cases, decompensation of concomitant diseases - in 84 (23.7%) patients, multiple metastases in the liver - in 48 (13.9%) observations, carcinomatosis of the abdominal cavity - in 32 (9.2%), invasion into the trachea - in 45 (13%), invasion into the aorta - in 53 (15.3%), multiple metastases in the lungs - in 59 (17.1%), and invasion into the main bronchi and the root of the lung - in 124 (35.8%) cases. It should be noted that the number of reasons for inoperability is much greater than the number of patients, as one patient in most cases had one, two or more complications of the main disease.This group of patients were performed the following treatment options:- the imposition of gastrostomy for nutrition – in 13(2,8%) cases;- symptomatic treatment – in 144(31%) cases;- minimally invasive endoscopic interventions – in 225(48,5%) cases.Gastrostomy in patients with inoperable stages of esophageal cancer was performed only in 13(2.8%) patients, although in the 70-90 years of the XX century it was the most common intervention to restore nutrition. Currently, the introduction of modern endoscopic technologies has significantly limited the indications for gastrostomy.Symptomatic treatment was performed in 144 patients after a comprehensive examination. After a comprehensive examination those patients were carried out symptomatic therapy with further observation and treatment in specialized oncological institutions.Patients with non-operable stages of esophageal cancer should strive to restore enteral nutrition to improve the quality of the rest of their lives. If earlier preference was given to gastrostomy, now modern minimally invasive endoscopic interventions have significantly limited the indications for gastrostomy, which is psychologically difficult to tolerate by patients and has its own surgical complications. Minimally invasive interventions were performed in 225 (48.5%) patients, as well as in 24 of 59 patients after diagnostic exploratory laparotomy and thoracotomy. Thus, minimally invasive methods of restoring enteral nutrition were used in 249 of 464 patients, which amounted 60.1%.Minimally invasive endoscopic interventionsWe used the following types of endoscopic interventions: endoscopic diathermotunnelization (EDT) - in 38 (15.3%), endoscopic bougienage (EB) - 18 (7.2%) and endoscopic stenting (ES) - in 193 (77.5%) patients. EDT and EB are relatively safe minimally invasive interventions; however, they only provide temporary nutritional restoration and require repeated sessions due to progressive tumor growth. Currently, EDT and EB (Fig. 1) are used only to expand the lumen of the tumor as a preparation for stenting. For EB we used a set of standard bougies and replaceable olive of our own design with a diameter of 0.9 cm to 2.0 cm (patent for a useful model "Esophageal bougie" FAP 01130). | Figure 1. The scheme of performing EDT and EB |

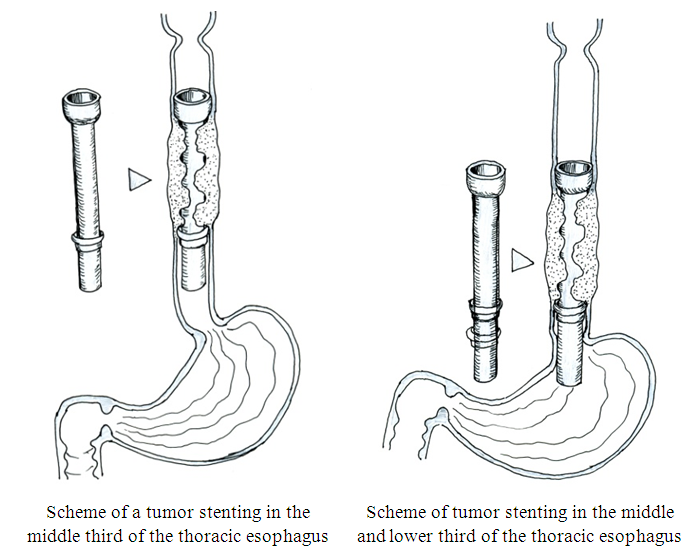

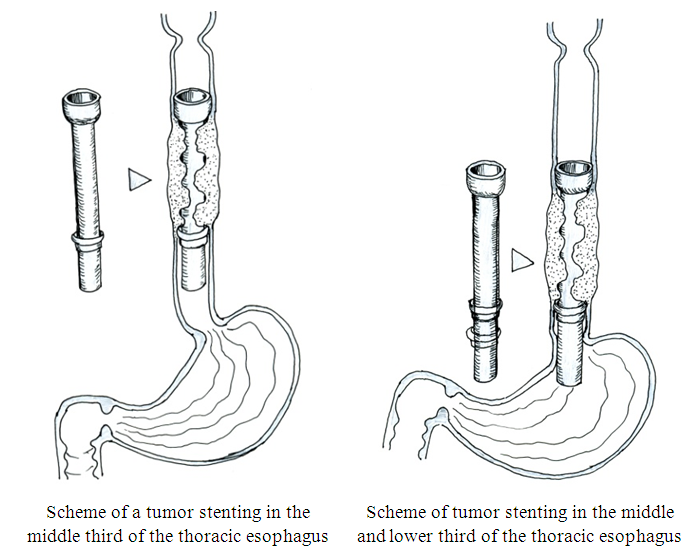

Endoscopic stenting with silicone stentsThe main point of using stenting (long-term intubation of the esophagus) is the possibility of oral nutrition, because tunnelization and bougienage cannot provide long-term restoration of esophageal patency due to the constant growth of a tumor that obstructs the lumen again. Thus, the stent restricts the stenosis of the tumor lumen, acting as a frame. However, stenting cannot be used in all patients, because two conditions are necessary: the presence of suprastenotic enlargement and circular lesion in order to prevent stent migration.We used a silicone tube stent of our own design, developed in the endoscopy department (patent for a useful model "Esophageal endoprosthesis stent" FAP 01101). The stent was made individually from a silicone tube with a funnel-shaped initial part to prevent its migration (Fig. 2). The required length and diameter were determined based on endoscopic and radiological data.  | Figure 2. Scheme of the thoracic esophagus stenting with silicone stents of our own design |

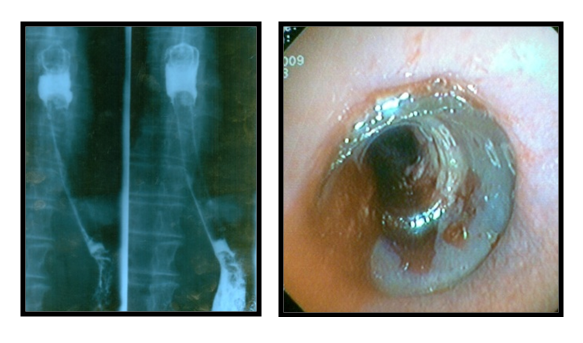

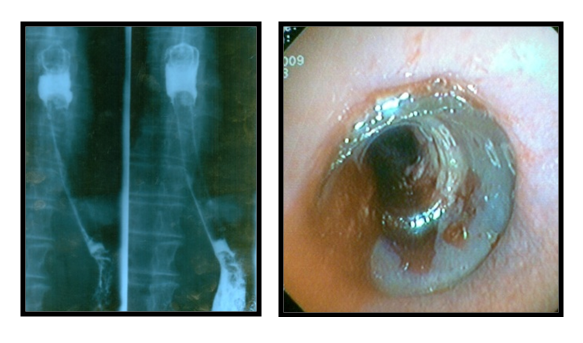

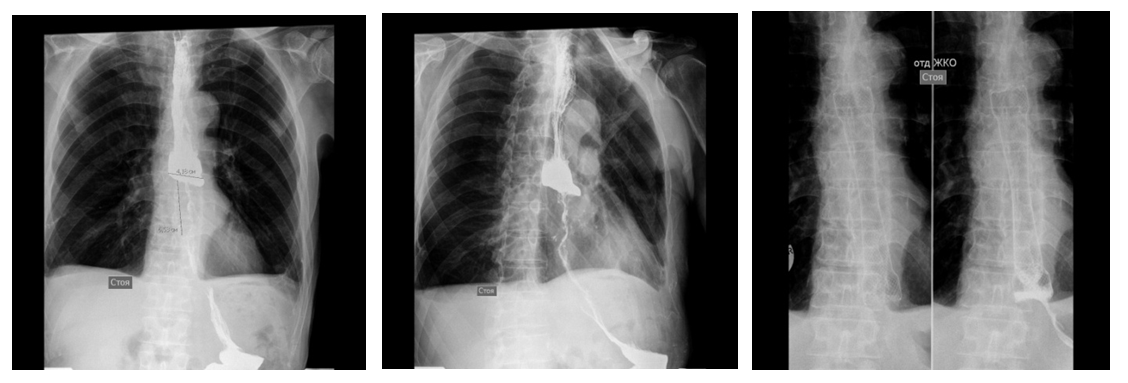

ES with silicone stents was performed in 157 patients. It was carried out under the control of endoscopy according to our own developed methods: on an endoscope device and on a bougie using a pusher tube. In 29 (18.5%) patients we managed to install a stent without preliminary expansion of the esophageal tumor lumen. Before stenting, EDT was performed in 28 (17.8%) cases, EB- in 80 (50.9%) case and EDT with EB in 20 (12.7%) patients. In the process of working out all stages of stenting, we are currently giving preference to endoscopic bougienage as preparation of the tumor lumen. After stenting, all patients were performed X-ray and endoscopic control to determine the correct placement of the silicone prosthesis (Fig. 3). | Figure 3. X-ray and endoscopy after stenting |

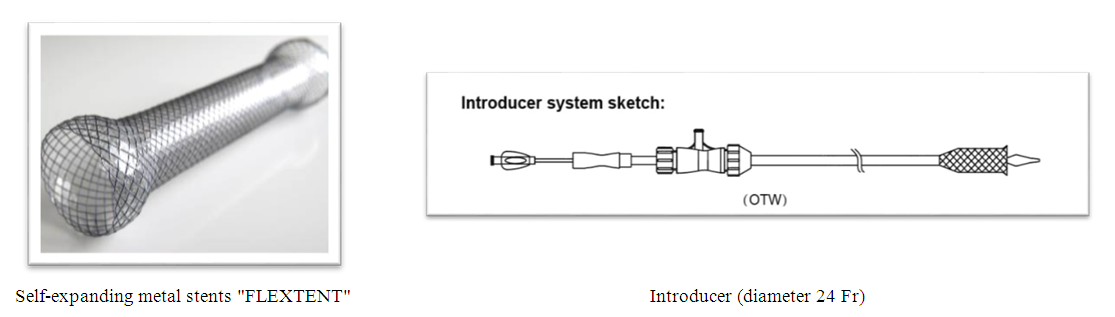

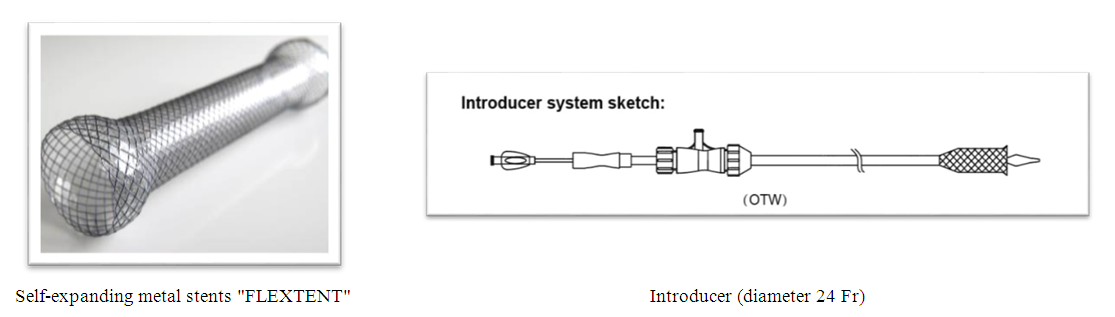

Early specific complications of endoscopic stenting: 1. Bleeding from the tumor zone - in 5 (3.2%) patients - in all cases conservative therapy was successfully carried out, however, in 2 patients endoscopic coagulation of the tumor was required for the purpose of final hemostasis;2. Injury of the esophagus - in 17 (10.8%) patients, in 7 (4.5%) of them - non-penetrating injury and in 10 (6.4%) patients - perforation of the esophagus. The diagnosis of tumor perforation was determined on the basis of the clinical picture, physical examination data and X-ray examination with a water-soluble contrast. At the same time, the patients were discharged in serious condition against the background of ongoing mediastinitis due to the flat refusal of the proposed emergency surgery;3. Severe pain syndrome - in 12 (7.6%) patients, apparently caused by a discrepancy between the tumor lumen and the stent diameter, in connection with which stents were removed in all patients and, after additional expansion of the tumor lumen they were performed repeated stenting.Late specific complications of endoscopic stenting: 1. Obturation of the stent with food was noted in 18 (11.5%) patients. The main reason for this complication is non-compliance with dietary recommendations when the patient swallows non-chewed food. In cases of obturation of the stent with food, fragmentation of the food lump was carried out under the control of endoscopy and the food was pushed over the distal end of the stent; 2. Migration of the stent into the stomach was noted in 3 (1.9%) patients. In all cases the stents were removed endoscopically followed by re-stenting in 1 patient. The rest of 2 patients refused stenting; 3. Migration (displacement) of the stent in the esophagus was registered in 3 (1.9%) patients. In all cases they were removed endoscopically followed by re-stenting;4. Pain syndrome not relieved by analgesics was observed in 8 (5.1%) patients. In all patients the stent was removed; 5. Obturation of the distal stent with a tumor was revealed in 7 (4.5%) patients. In all cases, tumor growth in the distal direction was determined, while diathermotunnelization of the occluding tumor was performed;6. Obturation of the proximal stent with a tumor was observed in 8 (5.1%) patients. In case of tumor obturation of the proximal end of the stent EDT was performed which was followed by additional re-stenting with a special extension (patent for a useful model of AIS RUz, No. FAP 01109 dated by 03.14.2016);7. Reflux esophagitis in the long-term period was observed in 12 (7.6%) patients, which was diagnosed both clinically and during control endoscopic examination. Esophagitis was caused by the absence of an antireflux valve in the installed esophagus, which caused the reflux of gastric juice and bile into the esophagus lumen.Among the nonspecific complications, 1 (0.64%) patient had an acute cerebrovascular accident which led to a lethal outcome.Endoscopic stenting with self-expanding metal stents (SEMS) There is an increasing emphasis on the use of self-expanding nitinol stents with an antireflux valve in the treatment of non-operable EC stages with dysphagia syndrome. Our department has experience in treating 36 patients with EC self-expanding metal stents "FLEXTENT" since 2018. All patients were performed stenting under the control of esophagoscopy without preliminary EDT and bougienage. The stent should be 4 cm longer than the formation because the length of the proximal and distal funnel (2 cm each) is taken into account (Fig. 4). | Figure 4. Self-expanding metal stent with introducer |

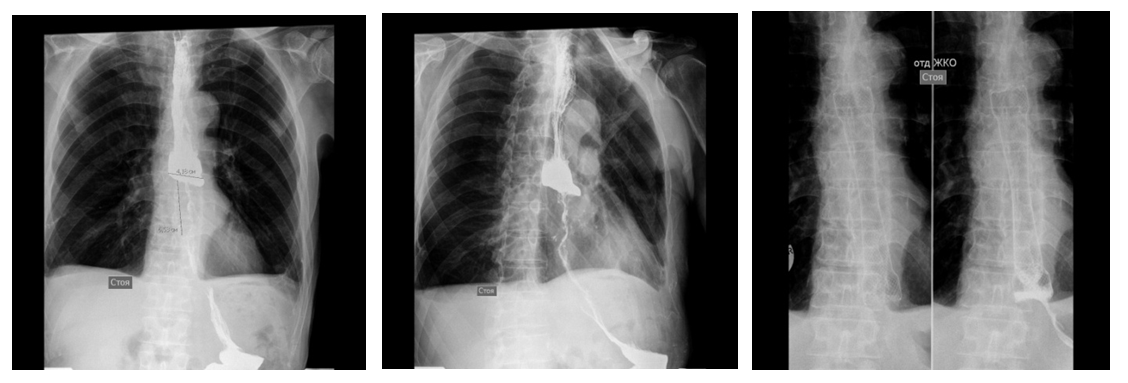

We used the following stenting technique: a metal guide is passed preliminarily below the tumor into the lumen of the stomach through the channel of the endoscope, the endoscope is removed. An introducer (24Fr) with a stent is passed into the tumor zone along the string with the guidewire. The correct position of the stent is checked under the X-ray control. Then the stent is removed from the introducer, while the stent is opened from the distal funnel towards the proximal one, after which it is fixed in the tumor zone. We conduct a control X-ray contrast study after removing the introducer (Fig. 5). | Figure 5. X-ray of esophageal tumor before and after stenting |

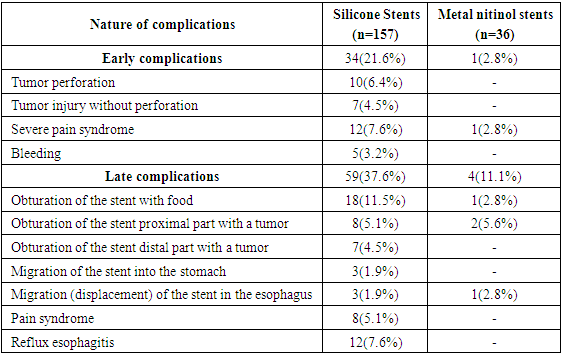

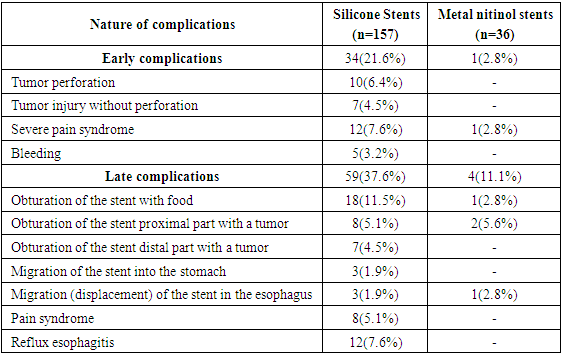

Among early specific complications (perforation, bleeding, severe pain syndrome, bleeding) 1 (2.8%) patient had severe pain syndrome, as a result of which the stent was removed without technical difficulties. Among the late complications 1 (2.8%) patient had distal migration of the stent. The patient was performed pull-up of a previously installed self-expanding stent with a good clinical result. In 2 (5.6%) cases 6 months after stent placement, tumor obturation of the proximal stent was noted and that is why a «stent-to-stent» self-expanding nitinol stent was installed.Comparative evaluation of early and late specific complications after the use of silicone and metal self-expanding nitinol stents with an antireflux valve is presented in Table 2. Table 2. Comparative evaluation of specific complications of stenting

|

| |

|

4. Conclusions

Modern treatment of esophageal tumors involves interdisciplinary cooperation and is intended for specialized departments of esophageal surgery. The installation of SEMS is a safe, effective and fast treatment option for dysphagia relief in compare with other methods. It has the most widespread use as the primary indication for exhausted patients with poor prognosis or with esophageal fistulas. New stent designs increase the benefits by reducing the frequency of complications that occur when using conventional silicone, rigid stents. A radioactive stent is preferred due to its greater efficiency in controlling dysphagia in patients with a longer life span. The use of a rigid plastic tube, only endoscopic dilation and only chemotherapy to mitigate dysphagia is not recommended due to the high frequency of complications and recurrent dysphagia. Particular attention should be paid to patients with recurrent dysphagia after radiation therapy requiring stenting due to an increased risk of complications.The authors declare no conflict of interests.This study did not include any funds.

References

| [1] | Dengina N.V. Modern therapeutic possibilities for esophageal cancer (In Russian) // Practical Oncology. – 2012. Vol.13, No 4. – P. 47 – 56. |

| [2] | Cools-Lartigue J, Jones D, Spicer J, Zourikian T, Rousseau M, Eckert E, et al. Management of dysphagia in esophageal adenocarcinoma patients undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy: can invasive tube feeding be avoided? Ann Surg Oncol 2015; 22: 1858–65. doi: https://doi.org/10.1245/s10434- 014-4270-9. |

| [3] | Waddell T, Verheij M, Allum W, Cunningham D, Cervantes A, Arnold D. European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) European Society of Surgical Oncology (ESSO) European Society of Radiotherapy and Oncology (ESTRO) Gastric cancer: ESMO-ESSO-ESTRO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2013; 24 (Suppl 6): vi57–vi63. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/ mdt344. |

| [4] | Park JH, Song HY, Kim JH, Jung HY, Kim JH, Kim SB, Lee H, et al. Polytetrafluoroethylene-covered retrievable expandable nitinol stents for malignant esophageal obstructions: factors influencing the outcome of 270 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2012; 199: 1380–6. doi: https://doi.org/10. 2214/AJR. 10. 6306. |

| [5] | Na HK, Song HY, Kim JH, Park JH, Kang MK, Lee J, et al. How to design the optimal self-expandable oesophageal metallic stents: 22 years of experience in 645 patients with malignant strictures. Eur Radiol 2013; 23: 786–96. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330- 012- 2661-5. |

| [6] | Park JH, Song HY, Shin JH, Cho YC, Kim JH, Kim SH, et al. Migration of retrievable expandable metallic stents inserted for malignant esophageal strictures: incidence, management, and prognostic factors in 332 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2015; 204: 1109–14. doi: https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.14.13172. |

| [7] | Battersby NJ, Bonney GK, Subar D, Talbot L, Decadt B, Lynch N. Outcomes following oesophageal stent insertion for palliation of malignant strictures: A large single centre series. J Surg Oncol 2012; 105: 60–5. doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/jso.22059. |

| [8] | Doosti-Irani A, Mansournia MA, Rahimi-Foroushani A, Haddad P, Holakouie-Naieni K. Complications of stent placement in patients with esophageal cancer: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. PLoS One 2017; 12: e0184784. doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0184784. |

| [9] | Wagh MS, Forsmark CE, Chauhan S, Draganov PV. Efficacy and safety of a fully covered esophageal stent: a prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc 2012; 75: 678–82. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016j.gie. 2011. 10. 006. |

| [10] | Stahl M, Mariette C, Haustermans K, Cervantes A, Arnold D.ESMO Guidelines Working Group Oesophageal cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2017; 24 (Suppl 6): vi51–vi56. doi: https://doi. org/10.1093/annonc/ mdt342. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML