-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2022; 12(2): 84-89

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20221202.03

Received: Jan. 7, 2022; Accepted: Jan. 21, 2022; Published: Feb. 15, 2022

Antibiotic vs Antidiarrheal in Treatment of IBS with Diarrhea

Rasmirekha Behera1, Sushant Sethi2

1Department of Pharmacology, I.M.S & SUM Hospital Bhubaneswar, India

2Department of Gastroenterology, Apollo Hospital Bhubaneswar, India

Correspondence to: Rasmirekha Behera, Department of Pharmacology, I.M.S & SUM Hospital Bhubaneswar, India.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2022 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

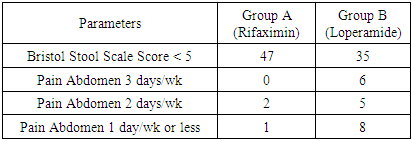

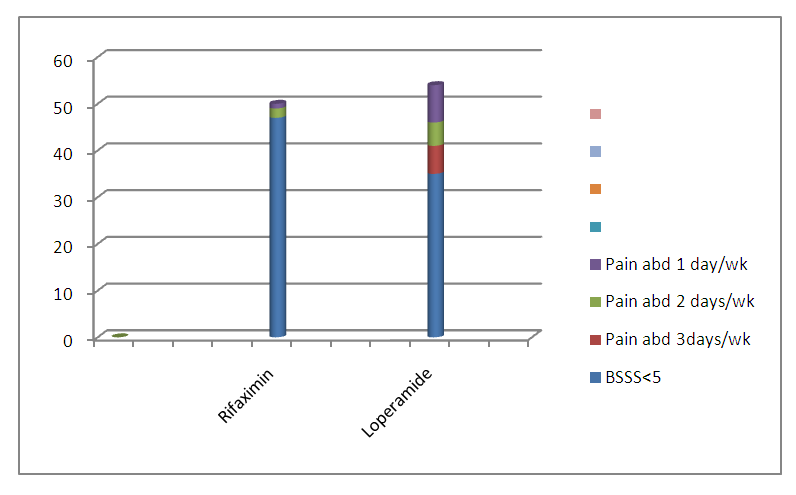

Introduction: Irritable bowel syndrome is a gastrointenstinal (GI) disorder characterized by altered bowel habits in association with abdominal discomfort or pain in the absence of detectable structural and biochemical abnormalities. IBS is a common GI disorder with a worldwide prevalence rate of 10-20% with women accounting for 70-75% of this. The diagnosis of IBS is based on the symptom based classification system known as Rome criteria. According to Rome IV diagnostic criteria there should be recurrent abdominal pain on an average at least 1 day/week in last 3 months, associated with two or more criteria. Further patients with IBS often experience impaired quality of life and their symptoms can have a significant negative impact on work and activities of daily life. The pathophysiology of IBS is unclear, but may include alterations in the gut microbiota, GI motility, visceral sensation, intenstinal permeability and the brain-gut axis and may also occur as the consequence of infection. The symptoms begin before 35 yrs of age in 50 percent of patients and almost all report symptom onset before 50 yrs of age. Although IBS is seen in the elderly, new onset of symptoms after age 50 may indicate other organic pathology and warrants more comprehensive evaluation. Aim: Efficacy assessment between Rifaximin and Loperamide in the treatment of IBS with Diarrhea. Methods: 100 IBS with Diarrhea patients were included in the study. Patients were diagnosed as IBS-D according to Rome IV diagnostic criteria. 50 patients (Group A) were treated with Rifaximin 1200mg/day and 50 patients (Group B) were treated Loperamide 2mg three times a day. Both the drugs were given for 2 weeks and were assessed in 0, 1 and 3 months intervals. Result: In this study it is observed that after administration of Rifaximin and Loperamide for 2 weeks out of 50 patients in Group A 47 patients were found to have BSSS<5 and it is 35 patients in Group B after 3 months of treatment. From table 1 & 2 it is observed that all the assessment parameters were improved in Group A patients in comparision to Group B patients after 1 and 3 months of treatment. Conclusion: Hence it can be concluded from the study that treatment with antibiotic Rifaximin shows significant improvement in symptoms of Irritable Bowel Syndrome in comparision to antidiarrheal Loperamide after 3 months.

Keywords: Irritable Bowel Syndrome, IBS-D, IBS-C, Rifaximin, Loperamide, Antibiotic, Antidiarrheal, Stool frequency, Abdominal bloating, Pain Abdomen

Cite this paper: Rasmirekha Behera, Sushant Sethi, Antibiotic vs Antidiarrheal in Treatment of IBS with Diarrhea, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 12 No. 2, 2022, pp. 84-89. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20221202.03.

1. Introduction

- Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a gastrointenstinal (GI) disorder characterized by altered bowel habits in association with abdominal discomfort or pain in the absence of detectable structural and biochemical abnormalities. [1] Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a common, often debilitating, gastrointenstinal disorder with a worldwide prevalence rate of 10%-20%. [2] The diagnosis of IBS is based on the symptom-based classification system known as the Rome criteria. [3] The diagnostic criteria the changes have included the Rome I criteria, which were revised to the Rome II guidelines. [5] and now to the most recent Rome III criteria to allow for ease of diagnosis. The Rome III diagnostic criteria simply state that a patient must have recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort at least 3d/month in the last 3 months and there is improvement with defecation, associated with a change in stool frequency or onset associated with a change in stool consistency. [4] According to Rome IV diagnostic criteria there should be Recurrent abdominal pain on average at least 1 day/week in the last 3 months, associated with two or more of the criteria related to defecation, associated with a change in the frequency of stool and change in the appearance of the stool. [5] According to WHO DMS-IV code classification for IBS and its subcategories, IBS can be classified as either diarrhea-predominant (IBS-D), constipation-predominant (IBS-C), or with alternating stool pattern (IBS-A) or pain-predominant. In some individuals, IBS may have an acute onset and develop after an infectious illness characterized by two or more of the following: fever, vomiting, diarrhea, or positive stool culture. This post-infective syndrome has consequently been termed “postinfectious IBS” (IBS-PI) [5] IBS is a remarkably common condition according to population-based studies. [6,7,8] IBS has been conceptualized as condition of visceral hypersensitivity(leading to abdominal discomfort or pain) and gastrointenstinal motor disturbances(leading to diarrhea or constipation) [9,7] There is increasing evidence regarding the role of immune activation in the etiology of IBS, which has mainly been shown in studies investigating mechanisms of IBS [10] Exposure to intenstinal infection induces persistent low grade systemic and mucosal inflammation, which is characterized by an altered population of circulating cells, mucosal infiltration of immune cells and increased production of various cytokines in IBS patients. Recent studies have also indicated an increased innate immune response in these patients by evaluating expression and activation of Toll-like receptors. [11] Additional studies are necessary to understand the precise mechanism of immune activation and its relationship to the development of IBS. [12] Small intenstinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) is prevalent in IBS, it remains unclear whether SIBO causes IBS. [13] Serotonin (5-HT) acting particularly through the 5-HT3 and 5-HT4 receptors, plays a significant role in control of gastrointenstinal motility, sensation and secretion. [14,15,16] Bristol Stool Form Scale (BSFS) described seven types of stool: Type 1 to Type 7. Stool Type 1 and 2 is being associated with constipation, while stool types 6 and 7 were associated with diarrhea. The BSFS is a convenient way for patients to describe their bowel habits. In addition, at the two extremes (Bristol stool type 1 and 2 or types 6 and 7) the stool form serves as a rough surrogate marker of colon transit. [17] Toll-like receptors (TLR) are membrane-bound receptors that recognize and bind microbial components in the GI mucosa, leading to an inflammatory response. [18] Expression levels of TLR-4 and TRL-5 genes in biopsy samples from the sigmoid colon of patients with IBS were 1-8 fold higher in comparable to healthy individuals. As well TLR-4 and TLR-5 protein levels in colonic crypts and the luminal surface were 4-6 fold greater, in patients with IBS-D compared with healthy individuals and TLR-4 gene expression levels correlated with stool frequency in patients with IBS. [19] Gastrointenstinal immune activation may be linked to visceral hypersensitivity and activated Immune cells localized near enteric nerves. [20] Visceral hypersensitivity (i.e altered pain perception to normal physiologic stimulation) is increased in patients with IBS compared with healthy individuals, and approximately half of patients with IBS exhibit hypersensitivity to rectal distension. [21,22,23] Alteration in the gut microbiota are thought to be involved in the pathophysiology of IBS. Indeed the gut microbiota is altered in patients with IBS in compared to healthy individuals. [24] There is no biological marker to explain the different symptoms of IBS. The majority of patients with IBS also have significant bloating and gas as part of their presentation, in addition to a degree of constipation, diarrhea and pain. [25] Rifaximin is a rifamycin antimicrobial agent, a rifampin structural analog. [26] Rifaximin inhibits RNA synthesis by binding to the β subunit of bacterial DNA-dependent RNA polymerase. [27] The addition of a pyridoimidazole ring to the rifampin molecule makes rifaximin a largely water-insoluble, poorly absorbable antibiotic, hence associated with few systemic adverse events. [28,29] Although its poor GI absorbability leads to low systemic blood levels, fecal concentration remains elevated with unchanged drug. [24] The increased solubility of rifaximin in bile leads to higher luminal concentrations and enhanced antimicrobial effects. [30] ACG guidelines currently recommended against the use of the antidiarrheal agent loperamide for use of the antidiarrheal agent loperamide for overall symptom improvement in patients with IBS. [31] For diarrhea-predominant IBS, 2 to 4 mg of loperamide up to four times a day can be effective. [32] Loperamide slows intenstinal transit, increases intenstinal water absorption, and increases intenstinal Water absorption. Loperamide is preferred to other opioid agents because it does not cross the blood brain barrier. Hence in this study the treatment outcome is compared between antibiotic (Rifaximin) and antidiarrheal (Loperamide) in patients diagnosed as IBS-D according to Rome IV diagnostic criteria.

2. Materials & Methods

- The study was conducted in Apollo Hospital Bhubaneswar in the department of Gastroenterology between the period of April 2021 to June 2021. Total 100 patients were included in the study. All the patients were diagnosed as IBS-D according to Rome IV criteria.50 patients were in Group A and 50 patients were in Group B. Group A patients were given Rifaximin 1200 per day and Group B patients were given 2 mg Loperamide thrice daily for 14 days. All patients were assessed after one month and three months of drug administration. Patients were assessed by parameters like Pain Abdomen, Stool frequency, Abdominal Bloating and Sense of urgency of Stool.Inclusion criterias:1. Patient Diagnosed with IBS with Diarrhoea (IBS-D) according to Rome IV criteria between the age 18 to 50 (Both male and female)2. Patient with History of wt loss3. Pain associated with loose or more frequent stoolExclusion criterias:1. Lactose malabsorption2. Women with pregnancy and breast feeding3. Patients below 18yrs or above 60yrs of age4. Irritable Bowel Disease (Chron’s disease & UC)5. Diarrhea caused by antibiotic medication6. Diarrhea caused by severe bacterial infectionStudy Design:This study is a Prospective Clinical study. It was conducted for a period of 3 months. Total 100 patients were included in the study and divided in to two groups containg 50 patients each. The patients were diagnosed as IBS according to Rome IV diagnostic criteria. Patients with Group A & B were treated with Rifaximin and Loperamide for 14 days respectively. All patients were assessed basing upon the different diagnostic parameters. Patients were assessed at 0, 1 and 3 months intervals.Statistical Analysis:All datas were analysed using Chi-square Test. p<0.05 considered as statistically significant and p<0.001 as highly significant.

3. Results

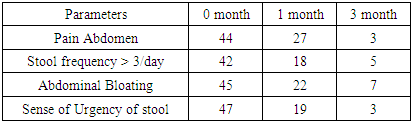

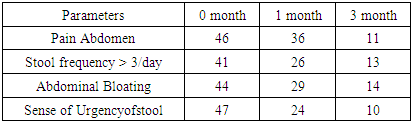

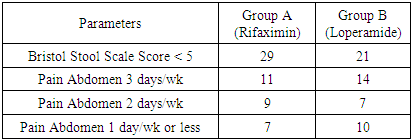

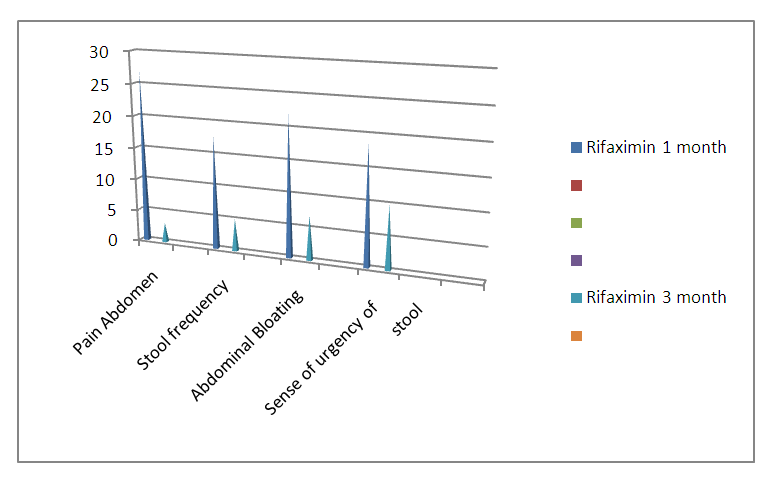

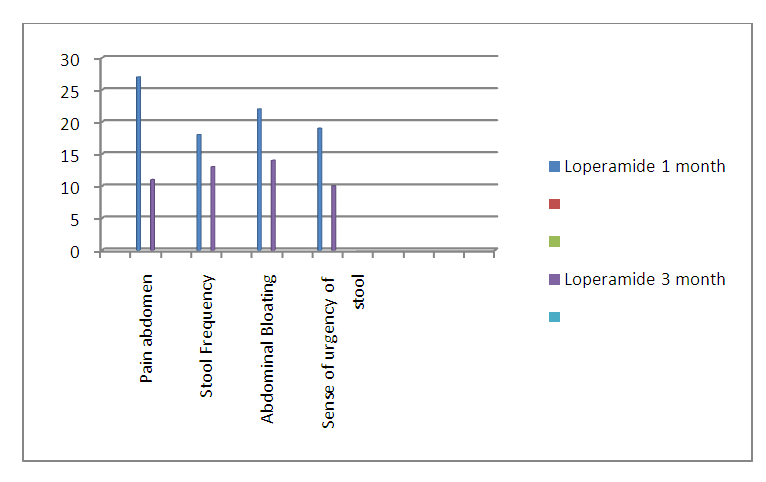

- Result of both Group A and Group B were compared basing upon the diagnostic criterias like Pain abdomen, stool frequency/day, abdominal bloating and sense of Urgency of stool.

|

| Graph 1. Comparision of Different diagnostic parameters after 1&3 months of the study in Group: A (Represented in no) |

| Graph 2. Comparision of Different diagnostic Parameters after 1&3 months of the study in Group: B (Represented in no) |

|

|

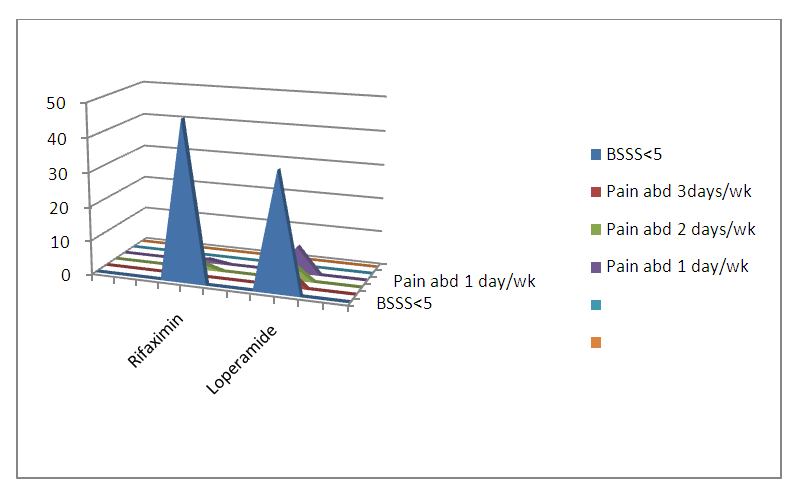

| Graph 3. Comparision of Frequency of Pain Abdomen and Bristol Stool Scale Score after one month between Group A and Group B |

| Graph 4. Comparision of Frequency of Pain Abdomen and Bristol Stool Scale Score after 3 months between Group A and Group B (Represented in no) |

4. Discussion

- The pathophysiology of IBS is multifactorial in nature, with interplay among several factors. SIBO is more prevelant in patients with IBS versus healthy individuals and was associated with specific demographic and disease characteristics (e.g female sex, IBS-D). IBS management has been primarily focused on symptomatic treatment until data revealed that patient suffering from IBS might have alterations in the gastrointenstinal flora, manifested by excessive bacteria in the small bowel, known as bacterial over growth. [33] Rifaximin improved GI mucosal inflammation i.e decreased levels of IL-6, IL-17 and TNF-α genes and normalized visceral hypersensitivity following a decrease in concentration of ileal bacteria.[34] Loperamide is effective for the treatment of acute diarrhea but not for abdominal pain and bloating which is often considered to be most bothersome IBS symptoms. [35] Rifaximin shows a lower degree of resistance compared to rifampin possibly because of high gut concentrations and extremely low systemic absorption. [36]

5. Conclusions

- Keeping in view of increasing the prevalence of IBS in general population this study is conducted in a tertiary care hospital. The findings of the study suggests that all the diagnostic parameters are improved in treatment with Rifaximin in comparision to Loperamide both after 1 month and 3 months of observation. The no of patients showing improvement in Bristol Stool Scale Score is more Rifaximin treated patients. It can be concluded from this study that treatment with antibiotic Rifaximin shows significant improvement in symptoms of Irritable Bowel Syndrome with diarrhea in comparision to antidiarrheal Loperamide. Hence Rifaximin a broad spectrum poorly absorbed oral antibiotic having more efficacy than Loperamide in treatment of IBS-D with added up advantages like excellent safety profile and limited cross-resistance with other antimicrobials.

References

| [1] | Drossman DA, Corrazziari E, Delvaux M, Spiller R, Talley NJ, Thompson WG, Rome III: The Functional Gastrointenstinal Disorders. McLean, VA: Degnon Associates, 2006. |

| [2] | Camilleri M, Choi MG. 1997, Review article: irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 11:3-15. |

| [3] | Drossman DA, Corazziari E, Talley NJ et al. Rome II. The functional gastrointenstinal disorders. Diagnosis, pathophysiology and treatment: A multinational consensus. Degnon Associates. |

| [4] | Occhipinti K, Smith JW. Irritable bowel syndrome: a review and update. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 2012; 25: 46-52. |

| [5] | Lacy B.E; Mearin F; Chang L, Chey W.D; Lembo A J et al Bowel Disorders. Gastroenterology 2016, 150, 1393-1407. |

| [6] | Holten KB, Wetherington A, Bankston L. Diagnosing the patient with abdominal pain and altered bowel habits: is it irritable bowel syndrome? Am Fam Physician 2003; 67: 2157-2162. |

| [7] | Drossman DA, Corazziari E, Tally NJ, Thompson WG, Whitehead WE. Rome II: The Functional Gastrointenstinal Disorders: Diagnosis, Pathophysiology, and Treatment: A Multinational Consensus. 2nd ed. McLean, VA: Degnon Associates, 2000. |

| [8] | Talley NJ, Spiller R. Irritable bowel syndrome: a little underst-ood organic bowel disease? Lancet 2002; 360: 555-564. |

| [9] | Boyce PM, Talley NJ, Burke C, Koloski NA. Epidemiology of the functional gastrointenstinal disorders diagnosed according to Rome II criteria: an Australian population-based study. Intern Med J 2006; 36: 28-36. |

| [10] | Drossman DA, Camilleri M, Mayer EA, Whitehead WE.AGA technical review on irritable bowel syndrome Gastroenterology 2002;123:2108-2131. |

| [11] | Matricon J, Meleine M, Gelot A, Piche T, Dapoigny M,Muller E, Ardid D. Review article: Associations between immune activation, intenstinal permeability and the irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharma-col Ther 2012; 36: 1009-1031. |

| [12] | Belmonte L, Beutheu Youmba S, Bertiaux-Vandaele N, Antonietti M Lecleire S, Zalar A, Gourcerol G et al. Role of toll like receptors in irritable bowel syndrome: differential mucosal immune activation according to the disease subtype. PLoS One 2012; 7. |

| [13] | Ishihara S, Tada Y, Fukuba N, Oka A, Kusunoki R et al. Pathogenesis of irritable bowel syndrome-review regarding associated infection and immune activation. Digestion 2013; 87: 204-211. |

| [14] | Spiegel BM. Questioning the bacterial overgrowth hypothesis of irritable bowel syndrome: an epidemiologic and evolutionary perspective. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011; 9: 461-49. |

| [15] | Spiller RC. Effects of serotonin on intenstinal secretion and motility. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2001; 17: 99-103. |

| [16] | Gershon MD. Review article: roles played by 5-hydroxytryptamine in the physiology of the bowel. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1999; 13 Suppl 2:15-30. |

| [17] | Lewis, S.J; Heaton, K.W. Stool form scale as a useful guide to intenstinal transit time. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 1997, 32, 920-924. |

| [18] | Mogensen TH. Pathogen recognition and inflammatory signaling in innate immune defenses. Clin Microbiol Rev 2009; 22: 240-273. |

| [19] | Shukla R, Ghoshal U, Ranjan P et al. Expression of toll like receptors, pro and anti-inflammatory cytokines in relation to gut microbiota in irritable bowel syndrome: the evidence for its microorganic basis. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2018; 24: 628-642. |

| [20] | Barbara G, Stanghellini V et al. Activated mast cell in proximity to colonic nerves correlate with abdominal pain in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2004; 126: 693-702. |

| [21] | Balemans D, Talavera K et al. Transient receptor potential ion channel function in sensory transduction and cellular signaling cascades underlying visceral hypersensitivity. Am J Physiol Gastrointenst Liver Physiol 2017; 312: G635-648. |

| [22] | Kuiken SD, Lindeboom R et al. Relationship between symptoms and hypersensitivity to rectal distension in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2005; 22: 157-164. |

| [23] | Van Wanrooji SJ, Van Oudenhove L et al. Sensitivity testing in irritable bowel syndrome with rectal capsaicin stimulations: role of TRPVI upregulation and sensitization in visceral hypersensitivity. Am J Gastroenterol 2014; 109: 99-109. |

| [24] | Pittayanon R, Yuan Y et al. Gut microbiota in patients with irritable bowel syndrome a systemic review. Gastroenterology 2019; 157: 97-108. |

| [25] | Talley N. (2006) Irritable bowel syndrome. Intern Med J 36: 724-728. |

| [26] | DuPont HL. Review article: the antimicrobial effects of rifaximin on the gut microbiota. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2016; 43 Suppl 1: 3-10. |

| [27] | Scarpignato C, Pelosini I. Rifaximin, a poorly absorbed antibiotic: pharmacology and clinical potential. Chemotherapy 2005; 51 Suppl 1: 36-66. |

| [28] | Descombe JJ. Dubourg D et. al. Pharmacokinetic study of rifaximin after oral administration in healthy volunteers. Int J Clin Pharmacol Res 1994; 14: 51-56. |

| [29] | Schoenfeld P, Pimentel M et al. Safety and tolerability of rifaximin for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome without constipation: trials. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014; 39: 1161-1168. |

| [30] | Darkoh C, DuPont HL. Bile acids improve the antimicrobial effects of rifaximin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2010; 54: 3618-3624. |

| [31] | Ford AC, Moayyedi P, Chey WD, et al. American College of Gastroenterology monograph on management of irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 2018; 113: 1-18. |

| [32] | Jailwala J, Imperiale TF, Kroenke K. Pharmacological treatment of the irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review of randomized, controlled trials. Ann Intern Med 2000; 133: 136-47. |

| [33] | Sharara AI, Aoun E et al. A randomized double blind placebo controlled trial of rifaximin in patients with abdominal bloating and flatulence. Am J Gastroenterol 2006; 101: 326-333. |

| [34] | Xu D, Gao J et al. Rifaximin alters intenstinal bacteria and prevents stress-induced gut inflammation and visceral hyperalgesia in rats. Gastroenterology 2014; 146: 484-496. |

| [35] | David J, Cangemi and Brian E. Management of irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea: a review of nonpharmacological interventions. Ther Adv Gastroenterol 2019, Vol. 12:1-19. |

| [36] | Du Pont HL. Biologic properties and clinical uses of rifaximin. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2011; 12: 293-302. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML