-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2021; 11(12): 896-906

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20211112.11

Received: Nov. 1, 2021; Accepted: Dec. 6, 2021; Published: Dec. 24, 2021

Iraqi Consensus for the Diagnosis and Management of Gastroesophageal Reflux/Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease in Infants

Ahmed Mohsen1, Antoine Farah2, Basim Al-Abdely3, Dhaigham Al-Mahfoodh4, Ghalib Thaher5, Hussein Al-kwailidi6, Hussein Aljwadi7, Khalaf Gargary8, Raid Umran9, Samer Jasim10, Thabat Rayyes11

1Pediatric Department, Jabber Ibn Hyan Medical University

2Pediatric Department, Saint Georges Ajaltoun Hospital, American University of Beirut

3College of Medicine, Al-Fallujah University

4Faiha Specialized Diabetes, Endocrine, and Metabolism Center

5Pediatric Department, Ibn Sina Teaching Hospital, Mosul, Iraq

6AL-Zahraa Teaching Hospital, Department of Pediatrics

7Department of Pediatrics, University of Misan

8Department of Pediatrics, University of Duhok

9College of Medicine, University of Kufa

10Department of Pediatrics, Children Welfare Teaching Hospital

11Pediatrics and Maternity Hospital, Babil

Correspondence to: Ghalib Thaher, Pediatric Department, Ibn Sina Teaching Hospital, Mosul, Iraq.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2021 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Gastroesophageal reflux (GER) is a normal physiologic condition that occurs in healthy infants and children without symptoms, esophageal injury, or any other complications. In contrast, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) occurs when the GER episodes are associated with complications. The symptoms and complications of GERD vary with age. In Iraq, there is a scarcity of published epidemiologic data, characteristics, and management patterns from Iraq on infantile GER and GERD. In order to fill this gap, this consensus meeting gathered a board of experts to share their experiences and clinical expertise on current trends in Iraq for the diagnosis and management of infants with GER/GERD. The purpose of this consensus is to provide pediatricians and pediatric subspecialists with a common resource for the evaluation and management of infants with GER/GERD in order to help standardize the care offered for those patients and develop local Iraqi treatment guidelines. In this context, attention should also be paid to parents’ education, including postural management and feeding techniques. In the case of mild or mild-to-moderate infantile GER or GERD, corn starch thickened formula is recommended. In moderate-to-severe GER or GERD cases, double thickened formulas with locust bean gum and tapioca starch are recommended for at least six months.

Keywords: Gastroesophageal reflux, Gastroesophageal reflux disease, GER, GERD, FGIDs, Formula, Iraq

Cite this paper: Ahmed Mohsen, Antoine Farah, Basim Al-Abdely, Dhaigham Al-Mahfoodh, Ghalib Thaher, Hussein Al-kwailidi, Hussein Aljwadi, Khalaf Gargary, Raid Umran, Samer Jasim, Thabat Rayyes, Iraqi Consensus for the Diagnosis and Management of Gastroesophageal Reflux/Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease in Infants, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 11 No. 12, 2021, pp. 896-906. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20211112.11.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Gastroesophageal reflux (GER), also called spilling and spitting up, is a physiologic condition that could be experienced by infants repeatedly throughout the day, mainly postprandial. It involves the backward involuntary motion of gastric contents from the stomach up into the esophagus. This spontaneous passage may be coupled with regurgitation or vomiting. Infantile GER presentation is mostly accentuated by regurgitation episodes, and to a lesser extent, by sporadic episodes of vomiting. Typically, GER is symptom-free, but whenever it causes significant symptoms that impact the quality of life, it is designated as gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). These symptoms include feeding difficulties, irritability, and poor weight gain [1], [2]. GERD symptoms are associated with complications that merit medical treatment [3].Within the first two months of age, about 70-85% of infants encounter regurgitation episodes [2]. By 3-4 months of age, reflux becomes at its worst case since spitting up, at least half of daily feeds is reported in 41% of infants [1]. However, 90-95% of infants experience resolution of GER by the age of one year [2], [4]. The prevalence of GERD symptoms in infants was estimated to be 26.9% [5]. As concerns the Middle East region, there is a paucity of published data on regurgitation prevalence [6].In a normal way, the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) and the crural diaphragm are the essentials of the anti-reflux barrier. The LES is located between the stomach and the esophagus and serves as a mechanical barrier between both of them. Backed by its composition of tonically contracted smooth muscle, LES can produce a high-pressure zone at the gastroesophageal junction that prevents gastric contents from traveling backward into the esophagus. Moreover, the crural diaphragm surrounds the LES, and hence, sets out further support by adding up a greater pressure in the distal esophagus. Failure of any of these two mechanisms poses a threat to the development of GER/GERD [2].Transient LES relaxation (TLESR) is a blunt fall in LES pressure, which makes it equals to that of the intra-gastric pressure. This decrease happens unassociated with swallowing over an extended period, which is relatively longer than other swallow-triggered relaxations [7]. In all ages, TLESR is the chief underlying mechanism for developing GER [8]. Many triggers can provoke TLESRs, such as straining with subsequent elevated intra-abdominal pressure and gastric distention, enhanced respiratory effort, coughing, and the postprandial postures designated as “semi-seated,” which are frequently seen in infants [2]. Aside from TLESRs; dietary influences, delays in gastric emptying, differences in acid production, and medication use are other factors that contribute to infantile GER [9]. With respect to GERD, a significant body of evidence has reported the relationship between delayed gastric emptying and the development of infantile GERD. Caloric density, volume, and osmolality of a consumed meal are key determinants of gastric emptying [2]. Additionally, cow’s milk protein allergy (CMPA) is deemed among the factors that contribute to the pathophysiology and development of infantile GERD [10], [11].The clinical presentation of GER infant is regarded as a seemingly healthy one with normal growth, no or minimum irritability, as well as painless, effortless, and non-bilious regurgitation. Yet; significant irritability, choking, coughing with feeds, or gagging are other signs that signify GERD or other diagnoses [2]. Diagnosis of GER/GERD commonly starts with a detailed history and physical examination [2]. A thorough review of feeding history is an important move to detect eating habits, overfeeding, or food triggers promoting reflux symptoms. Moreover, a review of medical history can distinguish predisposing factors to GERD [12]. Growth measurements should be assessed during physical examination in order to investigate for failure to thrive. Tenderness, distension, hepatosplenomegaly, peritoneal signs, and palpable masses should be evaluated through abdominal examination. Lung fields should be examined by auscultation for sounds such as wheezing and stridor. Neurological evaluation, including head examination, should investigate for any neurodevelopmental defects [13]. Diagnostic tests such as upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy, esophageal pH monitoring, and upper GI series are commonly used [14]. However, it has not been found that diagnostic testing is more reliable than detailed history and physical examination [15]. Thus, it should be reserved for specific conditions such as the presence of warning signs, atypical symptoms, and failure of initial treatments [12].Most infants with reflux improve with non-pharmacologic therapies (i.e. conservative measures) such as; positioning, formula thickening, changing formula, as well as alterations in meal frequencies [9], [12]. An effective approach to improve reflux is to change the infant’s body position. While awake, the left-side down and flat prone positions are recommended post-prandially since they are tied to fewer reflux episodes [9], [13]. However, a supine position should always be applied with sleeping infants to reduce the risk of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) [16]. A prone sleeping position may be considered after the age of 12 months since the risk of SIDS declines dramatically [13].The use of thickened feedings is a reasonable management strategy for infants with both GER and GERD [17]. It is well reported that thickened feedings diminish observed regurgitation, improve sleep, and possibly fail to thrive rather than reflux symptoms (such as apnea) and the total number of reflux episodes [9]. It is important to recognize that thickening with one tablespoon of rice cereal per ounce for a 20-kcal/oz formula raises the energy density to 34 kcal/oz. This should be borne in mind to avoid too much energy intake with long-term use of rice cereal or corn starch thickened feedings. For formula-fed infants, anti-regurgitant formulas that are commercially available in the market contain different constituents such as; potato starch, processed rice, corn starch, guar gum, and locust bean gum. These formulas are considered as an acceptable option that, when consumed in normal volumes, does not promote excessive energy intake. In infants allergic to cow’s milk protein, amino acid or extensively hydrolyzed formulas can decrease reflux episodes. For breastfeeding infants, immunogenic foods (such as eggs and cow’s milk) are preferential to be avoided by mothers to help improve infantile symptoms. Further to the use of thickened feedings; reducing feeding volumes, as well as, offering more frequent feeds may also reduce symptoms of infantile reflux [12], [17].Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and histamine-2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs) are commonly prescribed for GERD treatment [1]. Several studies have evaluated the efficacy of PPIs to treat infantile GERD. Interestingly, they demonstrated no improvement in symptoms such as; regurgitation, cough, crying, or back-arching, which make it doubtful whether PPIs could be of a definite benefit in such patients [4]. On the other hand, repeated use of antacids in infants should be made cautiously since milk-alkali syndrome or increased plasma aluminum levels have been reported with repeated use [1].Iraq is ranked as the 59th worldwide and the 16th in Asia in terms of area, with a population of over 41 million, and 13.9% are children under the age of 5 years [18]–[20]. There is a scarcity of published epidemiologic data, characteristics, and management patterns from Iraq on infantile GER/GERD. In order to fill this gap, this consensus meeting gathered a board of experts to share their experiences and clinical expertise on current trends in Iraqi infants with GER/GERD, with an ultimate aim to help standardize the care offered for those infants and develop local Iraqi treatment guidelines.

2. Consensus Development

- The present consensus was developed by a study group comprising ten Iraqi experts to generate local Iraqi guidelines for the management of infantile GER/GERD and obtain recommendations for diagnosis, treatment, and best practice. The panel consisted mainly of experts from different regions of Iraqi who are working in different healthcare sectors (university hospitals, ministry of health, or private sector). All members of the panel have previous clinical experience in the management of infantile GER/GERD. Also, most of the panel group have research experience and previous publications in the same field of interest. The experts were invited to participate in anonymous electronic voting on a predefined questionnaire followed by group discussion, correction, and modification of the statements. The questionnaire was designed and drafted after reviewing the previous guidelines and literature on clinical presentation, diagnosis, treatment, and best practices of GER/GERD. The online questionnaire using web-based SurveyMonkey® was organized in collaboration with an independent international expert and third party (RAY-CRO), which compiled the data and performed the analyses. The panel then met in executive session to discuss and address the comments and released the final statements.

3. GER in Iraqi Infants

3.1. Epidemiology and Clinical Presentation

- Functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) are a group of age-dependent, recurrent, chronic symptoms in infants and toddlers, which do not arise as a consequence of biochemical or structural defects. With age, the clinical presentation of any FGIDs noticeably differs in line with the stage of development. FGIDs in neonates and toddlers includes so many disorders such as; infant regurgitation, infant colic, cyclic vomiting syndrome, infant rumination syndrome, functional diarrhea, functional constipation, and infant dyschezia. In the first year of age; infant regurgitation, colic, dyschezia, functional diarrhea, and functional constipation are the principle FGIDs presented in this stage of life [21].With respect to infant regurgitation, a recent study that was conducted throughout the United States and included 1447 mothers revealed that the prevalence of infant regurgitation was 26% in healthy infants < 12 months of age [22]. It peaks at the age of 4 months in 67% of GER infants, and resolves in 90% of infants by the age of 12 months [21], [23]. A recent cross-sectional multicentre European study that included 2751 children; 1698 infants aged 0-12 months and 1053 children aged 13-48 months; revealed that the prevalence of any FGID in infants and toddlers was 24.7% and 11.3%, respectively. Further, the prevalence of infant regurgitation was 13.8%. The study concluded that younger age is associated with a higher prevalence of FGIDs [24].Consensus statementIraqi experts agreed that GER prevalence in Iraqi infants < 6 months of age is around 30%, with the utmost number of regurgitation episodes; > 5 episodes per day. However, the prevalence and frequency of episodes decrease remarkably by the age of 1 year, which are in concordance with the global estimates. The most common GER symptoms in Iraqi infants are; frequent regurgitation (ranked as the most prevalent), followed by vomiting, postprandial irritability, prolonged feeding or feeding refusal, and lastly, back arching.

3.2. Diagnosis

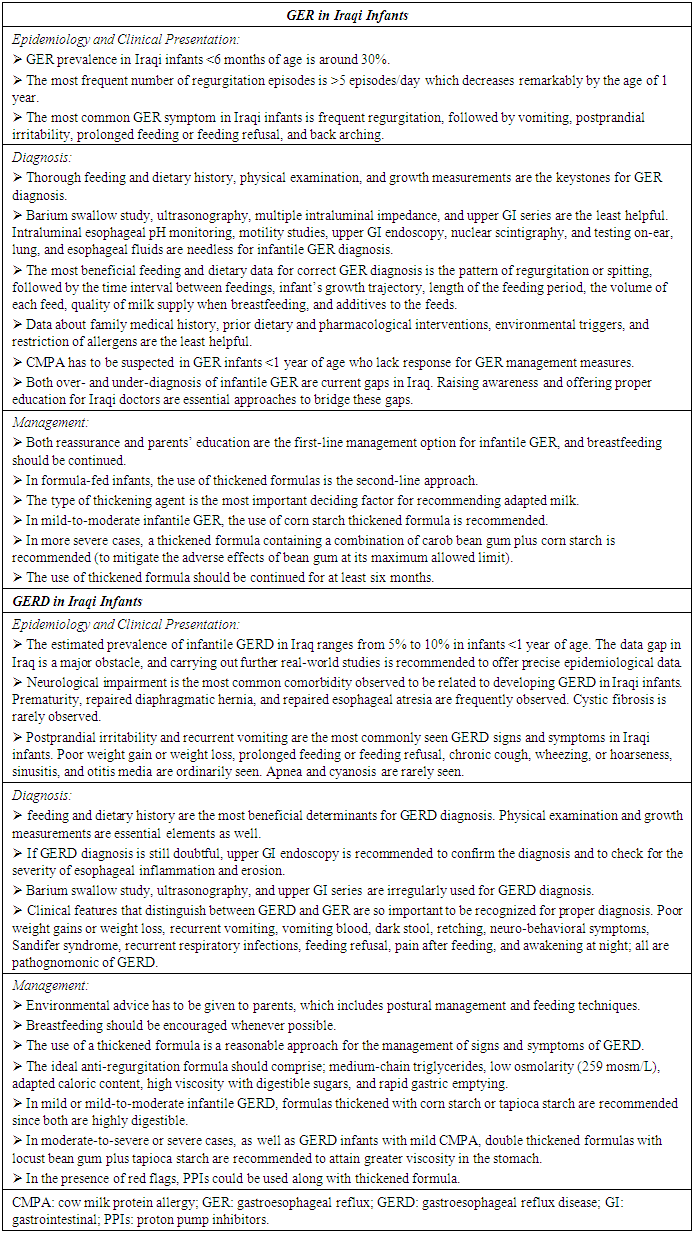

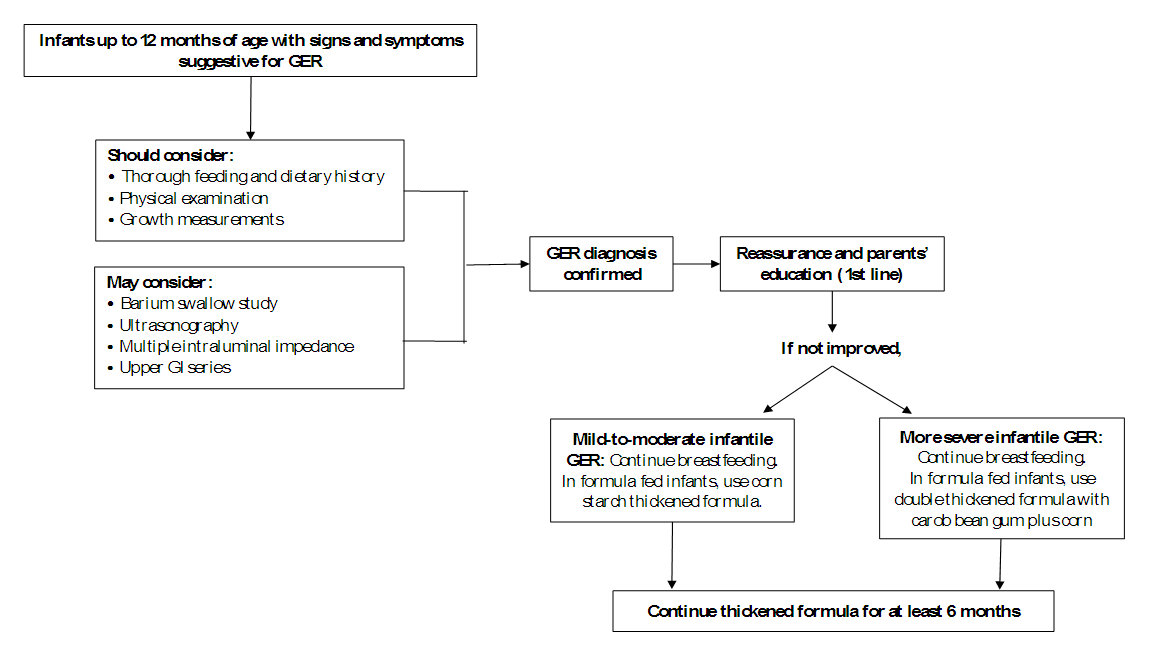

- Proper identification of infant regurgitation is a mainstay measure to avoid unneeded resource use [13]. GER diagnosis is principally confirmed with detailed history and physical examination [2]. In the vast majority of cases who seek consultation in the pediatric or gastroenterology clinics, diagnostic testing is not needed for establishing GER diagnosis [9].Since 1999, the year of the first publication of ROME criteria, a prompt increase in the number of publications on FGIDs has been perceived [22]. As per ROME IV criteria, healthy infants 3 weeks to 1 year of age should have the following 2 criteria jointly for proper GER diagnosis; firstly, regurgitation episodes ≥ two times/day for a minimum of three weeks; secondly, the infant should not present with hematemesis, aspiration, retching, failure to thrive, feeding or swallowing difficulties, apnea, or abnormal posturing (i.e. to exclude red flags) [21].Caution should be taken to distinguish regurgitation from other conditions such as vomiting, rumination, and GERD. For the first one, vomiting is a forceful expulsion of gastric contents that happens by virtue of a central nervous system reflex. These contents are expelled through the mouth backed by the coordinated actions of the esophagus, stomach, small bowel, and diaphragm. In other words, spitting up or regurgitation is an easy flow of stomach contents through the infant’s mouth, yet, vomiting is a “shooting out” rather than smooth dribbling [21], [25]. Rumination is the repeated swallowing of previously swallowed food. In this instance, swallowed food is reverted back to the pharynx and mouth, followed by chewing and swallowing again [21]. Once regurgitation causes complications that be worth medical treatment such as; esophagitis, feeding and swallowing difficulties, irritability, or any specified inflammation or tissue damage, it is appointed as GERD [1]. As per the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (NASPGHAN) and the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) 2018 clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of GER in infants and children, proper diagnosis of uncomplicated infantile GER could be established through history and physical examination. Both are generally considered to be sufficient for correct GER diagnosis but should be paralleled with close attention to warning signs [26]. Supporting this, an important consensus that reported the voting results of 22 key opinion leaders from all around the world revealed that 91% of them endorsed that diagnostic investigations are not indicated for the diagnosis and management of “troublesome regurgitation” [27].In many cases, GER can be associated, and even induced, by CMPA in infants younger than one year. CMPA and GER have been reported in 15% - 21% of infants with symptoms that are common for both, such as; failure to thrive, irritability, regurgitation, colic, vomiting, feeding refusal, sleep disturbances, and sideropenic anemia. Pediatricians should be mindful of this association to screen for possible CMA in GER infants < 1 year of age [28].Consensus statementIn Iraqi settings, experts agreed that thorough feeding and dietary history, physical examination (i.e. in order to rule out red flags), and growth measurements should be considered as the keystones for GER diagnosis. Barium swallow study, ultrasonography, multiple intraluminal impedance, and upper GI series are considered as the least helpful. Nevertheless, intraluminal esophageal pH monitoring, motility studies, upper GI endoscopy, nuclear scintigraphy, and testing on-ear, lung, and esophageal fluids are deemed as needless for infantile GER diagnosis. In addition, the most beneficial feeding and dietary data for correct GER diagnosis are ranked in the following order; the pattern of regurgitation or spitting (e.g. nocturnal, immediately postprandial, delayed postprandial, digested versus undigested), the time interval between feedings, infant’s growth trajectory, length of the feeding period, the volume of each feed, quality of milk supply when breastfeeding, and additives to the feeds. Nevertheless, a family medical history, prior dietary and pharmacological interventions, environmental triggers, and restriction of allergens are considered as the least helpful. The frequency of the association between GER and CMPA should be kept in mind by pediatricians. Thus, CMPA has to be suspected in GER infants < 1 year of age who lack response for GER management measures (Figure 1).

| Figure (1). Approach to diagnosis and management of infantile GER |

3.3. Management

- As per NASPGHAN and ESPGHAN 2018 clinical practice guidelines; parental education, reassurance, and anticipatory guidance are the recommended management measures for infants with GER. Breastfeeding should be encouraged in infants with physiological GER. In formula-fed infants, the use of thickeners or thickened formulas reduces the frequency of overt regurgitation and vomiting [26]. The use of thickened formula doesn’t merely reduce the frequency and severity of regurgitation, but it also mitigates the related discomfort in formula-fed infants. Thereby, it is indicated in case of persisting symptoms in spite of reassurance and proper volume intake in formula-fed infants [29], [30]. Conforming to this, an open multicenter study was conducted by Chevallier et al. on 64 bottle-fed infants presented with regurgitations and demonstrated ≥ 50% decrease in regurgitation frequency on days 3, 15, and 30 with the use of thickened formula compared to baseline [31]. A key element to be considered for the management of infantile GER is to continue the use of the thickened formula for ≥ 6 months. This recommendation is advocated by the vast majority of published studies in order to decrease regurgitation, along with improving the impact of parental reassurance [32].The efficacy of the anti-regurgitation formula is principally reliant on the type of thickening agent added, such as; rice starch, carob bean gum, and corn starch. With the use of rice starch thickened formula, a significant decrease in the total number of reflux episodes was demonstrated by Khoshoo et al., while no significant change has been observed in the reflux index [33]. In line with this, Ramirez-Mayans et al. conducted a study on fifty-two GER infants aged 15-120 days and reported no improvement in reflux parameters with the use of rice starch thickened formula [34]. For carob bean gum, Vandenplas and Sacre have demonstrated significant decreases in the total number of reflux episodes, long reflux episodes, and reflux index in 24 out of a total of 30 infants who were fed a carob bean gum. In the remaining 6 infants, all pH-monitoring parameters have returned to normal values [35]. With regards to corn starch, Moukarzel et al. have compared the efficacy of pre-gelatinized corn starch thickened formula with that of regular formula in 74 GER infants < 6 months of age. They reported significant decreases in reflux index, as well as, daily episodes of regurgitation and vomiting with the use of pre-gelatinized corn starch in those infants [36]. Another interventional, randomized, prospective study was conducted by Xinias et al. to assess the efficacy of a specifically treated corn starch formula versus standard infant formula. The investigators have enrolled 96 formula-fed infants, presented with > 5 episodes of regurgitation and vomiting per day, with a mean age of 93 days. The results revealed a significant reduction in clinical symptoms (i.e. frequency of regurgitation and vomiting), as well as all pH-metric parameters (i.e. number of reflux episodes > 5 min, reflux index, duration of the longest reflux episode) along with improved weight gain with the use of corn starch formula. Moreover, the results of this study proposed the advantage of corn starch over rice starch and carob bean in controlling acid reflux, since the observed reduction in esophageal acid exposure with corn starch cannot be confirmed with other agents [37]. From another angle, the adverse effects of anti-regurgitation formulas are also bound up with the type of thickening agent. The maximum allowed amount of modified starches in infant formula is 2.0 g/100 ml, with the exception of carob bean gum since its maximum level allowed is 1 g/100 ml which requires to be administered under medical supervision [30]. A significant increase in cough frequency was reported in the postprandial period with the use of rice starch thickened formula [38]. Moreover, difficulty in defecation [34] and arsenic load [39] were also reported in infants fed with rice thickened formula. Diarrhea and increased bowel movement have been demonstrated as common side effects with the use of carob bean gum thickened formulas [40], [41]. However, the use of corn starch in the maximum allowed limit of 2.0 g/100 ml reported no adverse effects [30].As concerns the pharmacological treatment for GER, the 2015 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines recommend against the use of acid-suppressing drugs (such as; PPIs and H2RAs) for the management of infantile overt regurgitation as an isolated symptom. Alike, it doesn’t indicate routine pharmacologic management in case of regurgitation without “red flags” or marked distress [42]. In line with this guidance, the practical algorithms published by Vandenplas et al. reported that 91% of a multinational experts’ panel considered the use of anti-regurgitation formula as a treatment measure for physiological GER, whilst 100% of them recommended against the use of drug treatment in such case. Interestingly, 77% of the experts didn’t recommend the use of drug treatment in case of troublesome regurgitation as well [27]. In keeping with the joint recommendations of NASPGHAN and ESPGHAN, no evidence has been proved to support empiric pharmacologic management for infants and young children with symptoms suggestive of GER [13]. Consensus statementThe experts’ panel agreed that reassurance and parents’ education are the most helpful management strategies, and thereby, are considered as the first-line management option for infantile GER. On the other hand, breastfeeding should be continued whereas, in formula-fed infants, the use of thickened formulas should be recognized as the second-line approach. The type of thickening agent is the most important deciding factor for recommending adapted milk. In mild-to-moderate infantile GER, it is recommended to use corn starch thickened formula. However, the thickened formula containing a combination of carob bean gum plus corn starch is recommended in more severe cases to mitigate the adverse effects observed with the use of bean gum at its maximum allowed limit. Further, the use of thickened formula should be continued for at least six months (Figure 1).

4. GERD in Iraqi Infants

4.1. Epidemiology and Clinical Presentation

- Generally, there is a paucity of pediatric-specific data on GERD incidence and prevalence, with the vast majority of available data are based on different questionnaires’ results [43]. Ruigómez and colleagues identified 1700 GERD children, aged 1–17 years old from the UK primary care database over a period of 5 years. They reported an incidence of GERD to be 1.48 per 1000 person-years (95% CI: 1.27–1.73) among infants aged 1 year [44]. The prevalence of GERD varies by age, and to a large extent, by the study as well. The estimated prevalence of GERD in infants ≤ 23 months of age ranges between 2.2% to 12.6% [43]. In relation to Iraq, no data were published about the incidence and prevalence of infantile GERD and, in general terms, in the Middle East region as well.Infants with certain comorbidities/risk factors are more likely to develop GERD, such as; neurological impairment, severe neuro-disabilities, repaired diaphragmatic hernia, congenital anomalies, repaired esophageal atresia, and cystic fibrosis [3], [4]. Typically, feeding difficulties, distress or excessive crying, poor growth, frequent otitis media, back-arching or posturing, recurrent aspiration pneumonia, and apnea are possible signs and symptoms in infants with GERD [4].Consensus statementThe experts estimated the prevalence of infantile GERD in Iraq to range from 5% to 10% in infants below the age of 1 year. This estimation was based mainly on a practical standpoint and is deemed to be in line with figures reported from other sides of the world. In this context, they emphasized that the data gap in Iraq is a major obstacle, and recommended for further real-world studies to be conducted in order to offer evidence-based epidemiological data.The experts’ panel consensus that neurological impairment is the most common comorbidity observed to be related to developing GERD in Iraqi infants. However, other comorbidities/risk factors are frequently observed such as; prematurity, repaired diaphragmatic hernia, and repaired esophageal atresia. Cystic fibrosis is rarely observed with Iraqi GERD infants. In relation to signs and symptoms, postprandial irritability and recurrent vomiting were recognized as the most commonly seen in Iraqi infants. To a lesser extent, poor weight gain or weight loss, prolonged feeding or feeding refusal, chronic cough, wheezing, or hoarseness, sinusitis, and otitis media were considered as ordinarily seen. Apnea and cyanosis are rarely seen in Iraqi infants with GERD.

4.2. Diagnosis

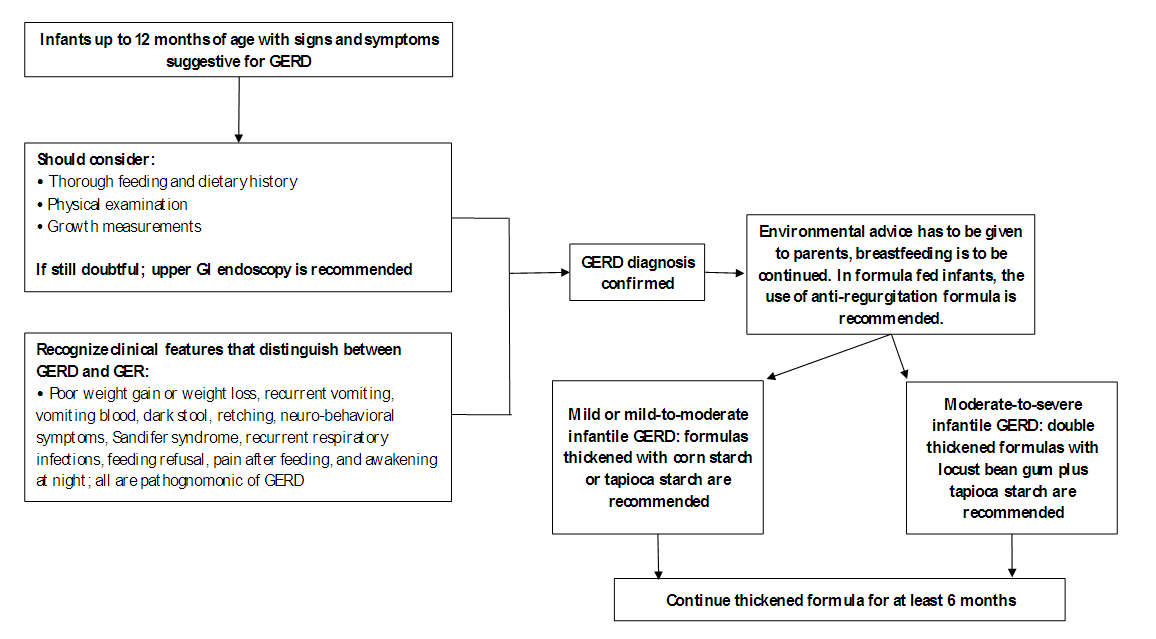

- Diagnosis of GERD in infants is premised mainly on the clinical history and clinical suspicion, which can be boosted by additional examinations. The primary goal of the additional diagnostic investigations is to seek out red flags, as well as; to confirm the diagnosis, qualify, and quantify GERD. Besides thorough history and physical examination; growth measurements, barium swallow study, ultrasonography, intraluminal esophageal pH monitoring, multiple intraluminal impedance, motility studies, upper GI endoscopy with/without biopsy, upper GI series, nuclear scintigraphy, testing on-ear, lung, and esophageal fluids are common examples for GERD diagnostic investigations that are used in different settings. However, with no single ‘gold standard’ investigation for infantile GERD diagnosis, those tests should be viewed in this light [4], [26].Consensus statementThe experts’ panel consensus that thorough feeding and dietary history is the most beneficial determinant for GERD diagnosis. Physical examination and growth measurements are recognized as essential elements for correct diagnosis as well. In some circumstances in which GERD diagnosis is still doubtful, upper GI endoscopy is recommended to confirm the diagnosis of GERD as well as to check for the severity of esophageal inflammation and erosion. Barium swallow study, ultrasonography, and upper GI series are irregularly used in Iraq for GERD diagnosis. In this respect, the experts agreed that it’s so important to recognize clinical features that distinguish between GERD and GER for proper diagnosis. Poor weight gains or weight loss, recurrent vomiting, vomiting blood, dark stool, retching, neuro-behavioral symptoms, Sandifer syndrome, recurrent respiratory infections, feeding refusal, pain after feeding, and awakening at night; all are pathognomonic of GERD (Figure 2).

| Figure (2). Approach to diagnosis and management of infantile GERD |

4.3. Management

- A step-wise approach is always adopted for GERD management. This approach applies non-pharmacological options first and then proceeds with the pharmacological measures only when needed [4]. Non-pharmacological options include several measures such as; positional therapy, massage therapy, complementary treatments (ex. prebiotics, probiotics, or herbal medications), and feeding changes [17], [26]. Omari and colleagues conducted a study that included 10 preterm infants and reported a significant reduction in both TLESRs and the number of reflux episodes with infants in left lateral positioning (LLP) compared to others in right lateral positioning (RLP) [45]. Another study by van Wijk and colleagues reported the same benefits of positioning, and the effect was immediate on both reflux and TLESRs [46]. However, and despite the reported benefits, the supine position is the only recommended one for infants to avoid the risk of SIDS [47]. As per NASPGHAN and ESPGHAN 2018 clinical practice guidelines for diagnosing and managing GER in infants and children, positional therapy is not recommended in sleeping infants to treat GERD symptoms (i.e. head elevation, lateral and prone positioning). Contrary, the working group suggests that head elevation and left lateral positioning could be considered to treat GERD symptoms in children. Concerning other interventions like massage therapy, it is not recommended to be used since lack of evidence supports its benefit to reduce signs and symptoms of GERD in infants. Likewise, complementary treatments such as; herbal medications, prebiotics, and probiotics are all not recommended for the treatment of infantile GERD since they had not been properly studied [26]. Other lifestyle interventions may be efficient strategies to manage GERD signs and symptoms in many infants such as; reducing feeding volume, increasing feeding frequency, changing formulas, modifying maternal diet in breastfed infants [17]. In full-term infants with no CMPA, the use of thickened feedings or the commercially available thickened formulas is considered as a reasonable approach for the management of infants with GERD [13], [48]. Different starches such as; rice, potato, tapioca, corn, and locust bean gum have been used for many years to thicken infants’ feeds [29]. A double-blind, prospective, randomized cross-over trial was conducted by Vandenplas and colleagues that enrolled 115 formula-fed infants with an age of 2 weeks to 5 months. They aimed at evaluating the effect of 2 anti-regurgitation formulas; ARF-1: non-hydrolyzed protein, locust bean gum; ARF-2: specific whey hydrolysate, locust bean gum plus tapioca starch. The results revealed a statistically significant decrease in the mean number of regurgitation episodes with both formulas (from 8.25 to 2.32 with ARF-1 and 1.89 with ARF-2), with a statistically significant difference between both formulas as well (P< 0.0091). Moreover, a statistically significant decrease was reported in the regurgitated volume with the use of ARF-2 compared to ARF-1 (P< 0.0265) [49].With regards to CMPA infants, a maternal elimination diet is recommended in breastfed infants with GERD. In other formula-fed infants, the use of an amino acid-based or extensively hydrolyzed protein formula is an appropriate management approach [17]. Vandenplas and Greef explored the potential impact of using a thickened extensive protein hydrolysate formula along with an elimination diet for those infants using a symptom-based score. The investigators reported that a significant reduction within one month was observed in the daily number of regurgitation episodes with the use of both versions; however, the reduction was greater with the use of thickened version compared to the non-thickened one (-4.2 ± 3.2 regurgitations/day vs. -3.0 ± 4.5, respectively) [50]. Several pharmacological treatment options for GERD in infants have been used such as; prokinetic drugs, mucosal surface barriers, gastric acid buffering drugs, and gastric anti-secretory agents [2]. However, the NASPGHAN and ESPGHAN 2018 clinical practice guidelines recommend against the use of domperidone and metoclopramide for the treatment of infants with GERD. The working group suggests that other prokinetics such as; cisapride, erythromycin, and bethanechol should not be used as first-line therapy for those infants. Moreover, the working group suggests against the chronic use of alginates and antacids for infantile GERD. For acid-suppressive therapy, PPIs are recommended as the first line in case of reflux-related erosive esophagitis. In case that PPIs are not available, H2RAs are recommended. However, the guidelines didn’t recommend acid-suppressive therapy for the treatment of crying/distress and visible regurgitation in otherwise healthy infants. Furthermore, the working group suggests against the use of these drugs in case of the presence of extra-esophageal symptoms (ex. cough, wheezing) unless if typical GERD symptoms are present [26]. In this context, it should be recalled that no PPI is FDA-approved for infants below the age of 1 year except esomeprazole. However, esomeprazole has been demonstrated to be an effective and safe treatment for erosive esophagitis caused by acid-mediated GERD and not symptomatic GERD [51]. It is also worth noting that many studies have reported numerous side effects with the use of acid suppression such as; gastrointestinal and respiratory infections, increased use of antibiotics, fractures, and increased risk of celiac disease [52]–[55]. Consensus statementThe experts’ panel highlighted that environmental advice has to be given to parents, which includes postural management and feeding techniques (such as; reducing feeding volume along with increasing frequency, modifying maternal diet in breastfed infants, the combination of feeding changes and postural management, and avoiding of environmental tobacco smoke). Breastfeeding should be encouraged whenever possible. The use of the thickened formula is a reasonable approach for the management of signs and symptoms of GERD.They agreed that the ideal anti-regurgitation formula should comprise; medium-chain triglycerides, low osmolarity (259 mosm/L), adapted caloric content, high viscosity with digestible sugars, and rapid gastric emptying. In the case of mild or mild-to-moderate infantile GERD, formulas thickened with corn starch or tapioca starch are recommended since both are highly digestible. In the case of moderate-to-severe or severe cases, as well as GERD infants with mild CMPA, double thickened formulas with locust bean gum plus tapioca starch are recommended for the sake of attaining greater viscosity in the stomach. In the presence of red flags, PPIs could be used along with thickened formula (Figure 2).

5. Conclusions

- Iraq represents a high GER prevalence of 30% in infants below six months of age. Simultaneously, the prevalence of GERD ranges from 5% to 10% in infants below the age of 1 year. Neurological impairment is the most common comorbidity observed to be related to developing GERD in Iraqi infants. The most beneficial determinant for GER/GERD diagnosis is the feeding and dietary history, in addition to physical examination and growth measurements. In this context, attention should also be paid to parents’ education, including postural management and feeding techniques. For the management, in case of mild or mild to moderate infantile GER or GERD, corn starch thickened formula is recommended; while, in moderate to severe GER or GERD cases, double thickened formulas with locust bean gum plus tapioca starch are recommended for at least six months.

|

6. Declarations

- Conflict of Interest: All authors declare no conflict of interest. Each author has revised and approved the final version of the manuscript independently. Financial support: This consensus was conducted under the sponsorship of Novalac, Middle-East which did not intervene in the design, voting process, writing, interpretation, preparation, and drafting of this document for publication.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- The authors would like to thank Dr. Radwa Ahmed Batran, Dr. Ahmed Salah Hussein, and Dr. Omar M. Hussein from RAY-CRO for their editorial support while drafting this manuscript.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML