Mirvarisova L. T., Anvarov Kh. E., Mirvorisova Z. Sh.

Implementation Group of the Project "Improvement of EMF Services in Uzbekistan", Republican Research Centre of Emergency Medicine, Uzbekistan

Copyright © 2021 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Abstract

It is necessary to introduce an emergency triage tool in order to quickly determine the clinical priorities of the increasing Uzbek emergency patients, perform appropriate treatment, and efficiently allocate emergency medical resources such as manpower, facilities, and equipments. Various types of 5-level triage tools are used worldwide, and consultants reviewed the most widely used tools such as MTS (Manchester Triage System), ESI (Emergency Severity Index), CTAS (Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale), and SATS (South African Triage Scale). After discussions with Republican Research Centre of Emergency medicine (RRCEM) experts, it was concluded that among these triage tools, CTAS was most suitable for the Uzbek emergency medical environment. Inadequate triage, lack of beds, spaces, and staffing were pointed out as problems through RRCEM statistics and on-site visits. For the stable introduction and settlement of the UTAS, the consultants suggested the following: 1) It is essential to develop and implement standardized educational programs for triage practitioners. 2) The number of beds needs to be adjusted and expanded. 3) It is necessary to secure the triage area and the yellow zone, and to provide essential equipment. 4) It must be considered to reinforce the manpower of triage practitioners, and to arrange a dedicated yellow zone medical staff.

Keywords:

Emergency medical care, Triage, UTAS

Cite this paper: Mirvarisova L. T., Anvarov Kh. E., Mirvorisova Z. Sh., The Results of the Expert Survey for the Implementation of the Triage System of Patients – UTAS in the RRCEM and Its Branches, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 11 No. 4, 2021, pp. 346-352. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20211104.18.

1. Introduction

The number of patients using emergency rooms worldwide is increasing rapidly. An increasing number of emergency departments (ED) visits has posed a challenge to health systems in many countries. As the number of patients visiting the ED increases, a number of problems arise, such as overcrowding in the ED, rising medical expenses, lowering the satisfaction of patients and caregivers, and the spreading of infectious diseases. Serious problems can arise when the number of ED patients exceeds the acceptable limits of emergency medical resources. The most dangerous situation is that patients with high severity do not receive adequate treatment in a timely manner.Emergency departments are provided with patients at various levels of urgency and severity. Therefore, various types of triage tools have been developed and used in each country in order to quickly determine the clinical priorities of these patients, perform appropriate treatment, and efficiently allocate emergency medical resources such as manpower, facilities, and equipment. Under-triages can put patients at risk, and over-triages can cause limited resources to be occupied first, which interferes with the actual need for serious patients. Therefore, fast and accurate patient triage is critical for successful ED operation.

2. Materials and Methods

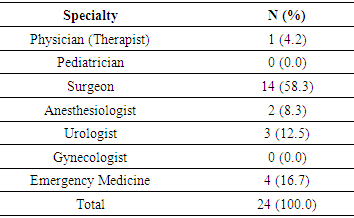

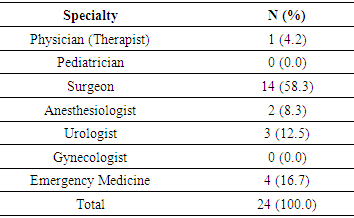

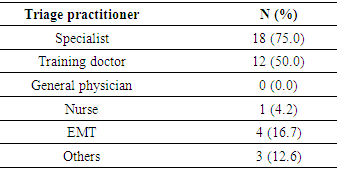

More than 180,000 patients are visited annually at RRCEM in Uzbekistan. In particular, emergency medical services provided free of charge to all patients regardless of citizenship, gender, race, and religion are expected to accelerate the growth rate of ED patients. The resulting overcrowding in the ED can be detrimental to the patient as a result. Therefore, it is time to develop and apply the triage tool based on scientific evidence.Through several webinars, CTAS was selected as the most appropriate triage tool for the Uzbek emergency medical environment. The final triage tool that modified CTAS was named the Uzbekistan Triage and Acuity Scale (UTAS). Two times of expert surveys and several webinar discussions were conducted to revise and introduce CTAS. Most experts agreed on the following: 1) In the Uzbek, where the concept of triage is still unfamiliar, it is appropriate that a doctor is in charge of a triage practitioner, 2) It is necessary to properly classify the patients into the red, green, and yellow zones of RRCEM, 3) Reassessment is required for the waiting patients. It was decided to name it the UTAS by introducing CTAS, and the modified details are as follows. 1) Pain score is measured by a triage practitioner, 2) External respiratory function is not measured at admission, 3) The reference age for children is 18 years or younger. 4) The criteria for fever in children is set based on 38°C. Based on the above, the final triage protocol was suggested.For the introduction of UTAS, an analysis of the current situation regarding medical personnel and equipment was conducted. And two expert surveys were conducted on:• UTAS operation• Triage practitioners in the UTAS• Education and quality management• Time limit and color by level• Considerations for age, trauma, and pain• ReassessmentThe task force of experts was made up of the directors and specialists of the RNCEMP and its regional branches. The main parameters for the UTAS system, put forward by the RSCEMP specialists, were:CTAS was revised based on an expert survey and webinar discussion, and the UTAS was finally confirmed. Considerations for the UTAS operation with RRCEM experts are as follows:• Pain• Level of consciousness• Appropriateness of level according to breathing• Hemodynamic status• Body temperature• Congenital or acquired bleeding disorder • Mechanism of injury• Consideration for childrenTo develop a triage tool suitable for the Uzbek emergency medical environment, existing triage tools widely used around the world were reviewed. Through discussions of experts, it was judged that it was most appropriate to introduce a valid triage tool and apply it after modification and proceeded afterward.Currently, Uzbekistan’s RRCEM uses a three-level classification system of Red, Yellow, Green. The overall patient’s condition is evaluated, and if the patient is serious, he/she is placed in the red zone. Of these, the level of consciousness is the most important parameter. There is no specified protocol for the red zone. However, severely injured patients with a GCS score of 9 or less, patients with unstable vital signs, dangerous chief complaints (e.g., chest pain, hemiplegia, gastrointestinal bleeding, etc.), life-threatening conditions (e.g., chocking, massive hematemesis, etc.) are placed in the red zone. Except for those who are placed in the red zone, all patients wait and receive treatment from each specialist assigned according to their chief complaints. Vital signs are not measured while waiting, and the order of seeing a doctor is not the priority according to severity, but the order of visit to the emergency department. If it is determined that observation is necessary after treatment by a specialist, the patient is placed in a yellow zone. If the patient needs surgery, he/she will be hospitalized or prepared for surgery immediately. Most of the patients who do not correspond to these conditions are discharged after prescription. At the first stage, UTAS is proposed to be used in the RNCEMP, but in the future it is possible to distribute this scale to all institutions in Uzbekistan. Thus, the possibility of using the UTAS scale in the RNCEMP was studied.The first expert survey included questions about the operation of UTAS, education and quality management, time limit and color characteristics indicating the appropriate level of triage, considerations regarding age, injuries, pain, and re-evaluation of patients. The first survey was conducted on 30 experts belonging to RRCEM and regional hospitals. Of these, 24 experts completed the questionnaire, and the response rate was 80%. Respondents’ majors are as follows. Table 1. Specialty of the Respondents

|

| |

|

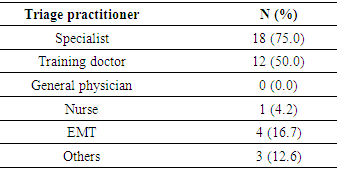

Accordingly, when asked whether the triage for emergency patients should be specified in Uzbekistan for the operation of UTAS, all experts answered ‘yes’. The questions about the appropriate level of legislation were ‘Presidential Decree’ 14 (58.3%), ‘Decree of Cabinet’ 3 (12.5%), and ‘Decree of Ministry of Health’ 6 (25.0%). Most of the respondents answered that specialists would be appropriate as a triage practitioner. This is in contrast to the fact that trained nurses are playing triage practitioners in many countries.Table 2. Who is the appropriate triage practitioner? (Multiple selections possible)

|

| |

|

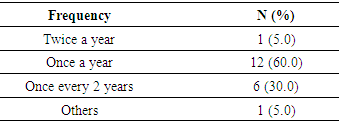

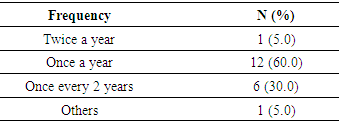

The UTAS should strive to increase reliability among triage practitioners through education. To this end, 21 experts (87.5%) agreed to the mandatory regular education by the government, and 2 (8.3%) opposed it. Other comments were that it is more important to monitor whether triage is properly implemented (1; 4.2%). The response to the frequency when regular education was conducted by the government was as follows. The other comment was that new and refresher education should be separated, and education hours should be differentiated.Table 3. Frequency of regular training for the UTAS

|

| |

|

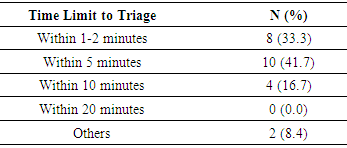

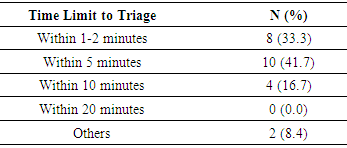

The CTAS recommends that the triage be performed as soon as possible after the patient arrives in the ED. Therefore, the highest opinion was that the door to triage time of fewer than 5 minutes is appropriate for the patient to visit the ED and meet the triage practitioner.Table 4. Responses to the Door to Triage time

|

| |

|

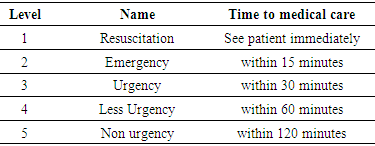

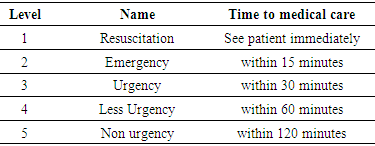

The CTAS sets a time limit until seeing a doctor. The name and the target time by level are as follows: Table 5. Time to medical care by level in the CTAS

|

| |

|

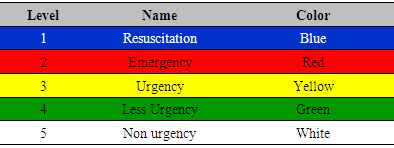

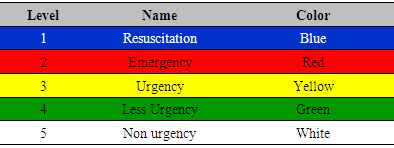

In this regard, the experts asked whether it is necessary to limit the time it takes for a patient to visit the ED and start receiving specialist treatment in the UTAS system, and 17 (70.8%) experts answered ‘yes’. Of these, 11 (64.7%) responded that it was necessary to limit door to specialist time according to the level, and 6(35.3%) answered that it would be better to see them as soon as possible without a fixed time limit. The CTAS classifies colours by level as follows: Table 6. Colour by level in the CTAS

|

| |

|

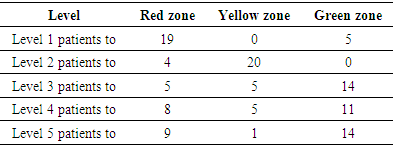

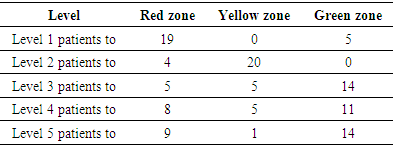

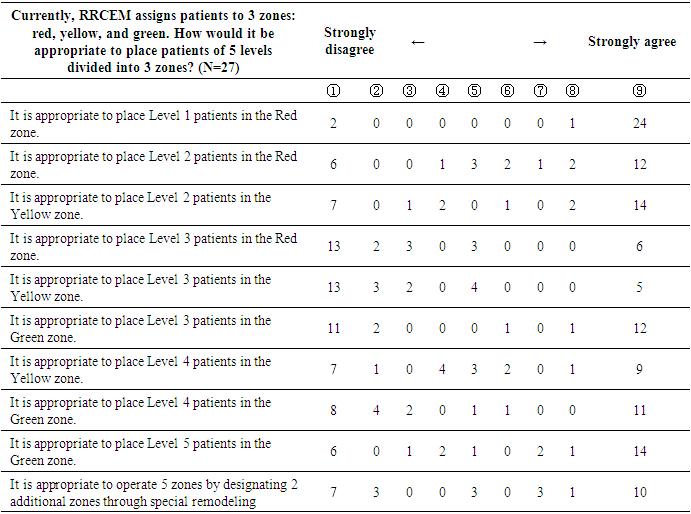

Like CTAS, 10 experts (83.3%) answered ‘yes’ to the question of whether it is necessary to separate colours for each level in the UTAS. Currently, RRCEM assigns patients to 3 zones: red, yellow, and green. When using the UTAS, a 5-level triage, how should patients in each zone be arranged? 18 (75%) said that according to the level, patients should be properly placed and operated in the current 3 zones. 5 (20.8%) responded that it would be better to operate 5 zones by designating two additional zones through special remodelling. Also, the question was asked that ‘How would it be appropriate to place patients of 5 levels divided into current 3 zones?” In the table below, for example, out of a total of 24 experts, 5 responded that it is appropriate for severely ill patients corresponding to Level 1 to be placed in the current green zone. This is an important question that asks how to place patients in the absence of 5 zones even though UTAS was introduced. However, after checking the result of this question, it was confirmed that the experts’ degree of understanding about triage was low. Therefore, this item was to be asked again in the second survey with detailed explanation.Table 7. Response results for the method of place 5-level UTAS patients into 3 zones

|

| |

|

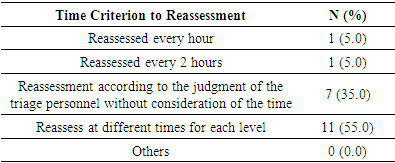

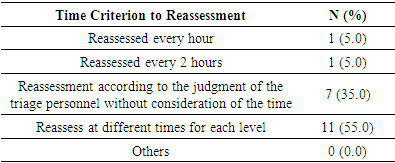

The 18 experts (75.0%) agreed to the question of whether age should be considered when classifying UTAS. All of these 18 experts responded that it was necessary to differentiate triage between children and adults. However, only 11 experts (61.1%) answered that it is necessary to separate the elderly. 19 (79.2%) answered that the UTAS should operate trauma patients as an independent triage system. This was a question to confirm whether a separate triage is advantageous in treating trauma patients, such as the existence of a building in charge of trauma even in RRCEM. However, as a result of discussions with experts of RRCEM, it was determined that a separate system was not necessary because the main reception department is responsible for severe trauma. Consideration of pain is an important issue in many triage tools. The CTAS implies the concept of urgency as well as patient severity. The urgency is less related to the patient's outcome but the patient's discomfort (such as pain) is severe, and thus the need for quick treatment is high. Urgency is often not directly related to the prognosis, but with the emphasis on patient's right and quality of life, reducing the patient's discomfort is recognized as a priority of treatment. Therefore, it is stipulated to consider the patient's subjective pain in the CTAS classification process. In other words, the CTAS classifies 1-3 points as mild pain, 4-7 points as moderate pain, and 8-10 points as severe pain, based on the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) that the patient says, ad determines the final level. Therefore, experts were asked whether pain should be considered in the process of applying UTAS, and 20 (83.3%) answered 'yes'. However, when asked whether to administer pain killers after triage and before being seen by specialists, most of the experts responded 'no' (19, 79.2%). When asked if reassessment was necessary for patients waiting after the initial triage of UTAS, 20 (83.3%) answered 'yes'. However, there was a difference in the response to the time criterion for reassessment and is as follows: Table 8. Time criterion to reassessment

|

| |

|

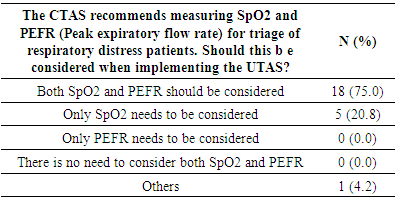

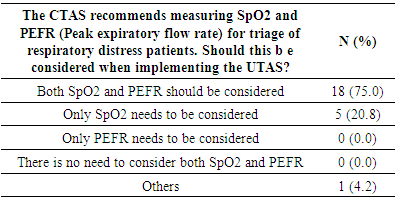

In the CTAS, first and second-order modifiers are placed to determine the triage level. The first order modifiers include vital signs, pain, bleeding disorders, and mechanism of injury, and the second-order modifiers include blood sugar level and degree of dehydration. Therefore, the next question is how to consider this in the UTAS. Table 9. Respiratory distress

|

| |

|

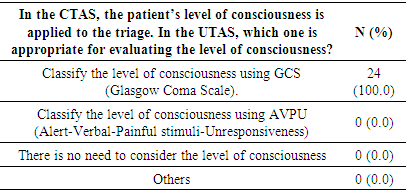

18 (75.0%) said that both SpO2 and PEFR should be measured in patients with respiratory distress. As a result of discussion with RRCEM experts, it was concluded that only SpO2 was considered because the emergency department did not measure PEFR. All experts agreed that it is appropriate to evaluate the level of consciousness by GCS. Table 10. Measurement of the level of consciousness

|

| |

|

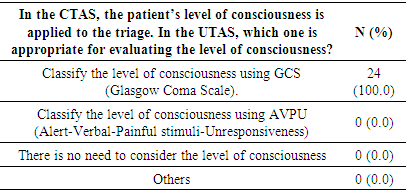

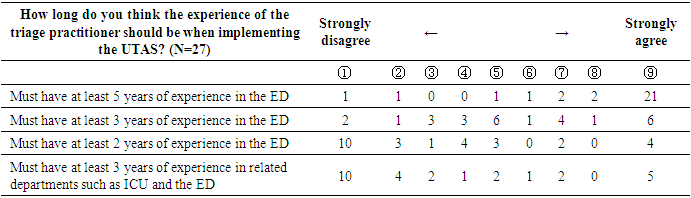

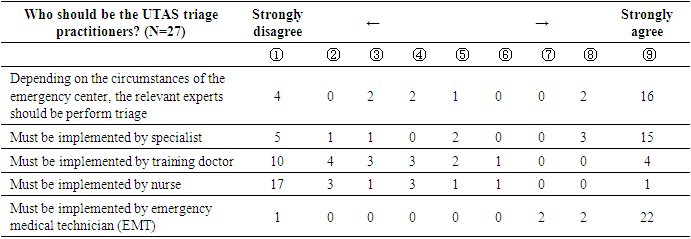

Most experts thought that the mechanism of injury and blood sugar level should be considered when implementing UTAS (22, 91.7% and 21, 87.5%, respectively).After the pre-emptive introduction of the UTAS in RRCEM, the UTAS is likely to be expanded and operated to emergency hospitals throughout Uzbekistan. Therefore, it was necessary to draw an agreement on the main operation method by asking for the opinions of experts. However, as a result of the first survey, it was judged that the respondents did not understand accurately the triage system. Therefore, in the second survey, the triage system and the CTAS classification process were explained in detail before the question. After that, we asked about the degree to which they agreed to the contents presented. The second survey was marked using a 9-point Likert scale according to the degree of agreement with each question. If the expert disagrees with the presented sentence, he/she marks it at number 1, and if the expert agrees strongly, it is indicated at number 9. Interpretation of the results is divided into 1 to 9 points on the Likert scale, where 1-3 points are agreed as “Disagree,” 4-6 points are not agreed, and 7-9 points are agreed to be “Agree.” The case where the consent rate for each sentence was 60% or more was adopted as the agreed item, and it is indicated in yellow in the table below. The second survey was conducted on 30 experts belonging to RRCEM and regional hospitals. Of these, 27 experts completed the questionnaire, and the response rate was 90%. 6 (22.2%) were from RRCEM and 21 (77.8%) were from the branch hospital. Surgery (19, 70.4%) was the most common major, followed by internal medicine and urology in 2 each (7.4%, respectively), anaesthesiology and emergency medicine in 1 each (3.7%, respectively), and other majors in 2 (7.4%). As for the position of the respondents, the director of the institution had the most with 10 (37.0%). This was followed by the head of the reception department (8, 29.6%), the deputy director of the institution (4, 14.8%), and the specialist of the reception department (2, 7.4%). There were 3 other positions.As a result of confirming the degree of consent to the question of who thinks the triage practitioner should be when classifying the UTAS, it was agreed that 66.7% of experts agree with item “Depending on the circumstances of the emergency centre, the relevant experts should perform triage”, “Must be implemented by specialist” and 96.3% of experts in item “Must be implemented by EMT”. On the other hand, it was agreed that 63.0% and 77.8% of experts disagree on the items that “Must be implemented by a training doctor” or “Must be implemented by a nurse”, respectively. When UTAS is introduced in the future, it is necessary to operate a training curriculum targeting specialists and EMTs first when related experts implement UTS according to the circumstances of the emergency centre, and to expand the targets later.Table 11. Respondents' degree of agreement: Triage practitioners in the UTAS

|

| |

|

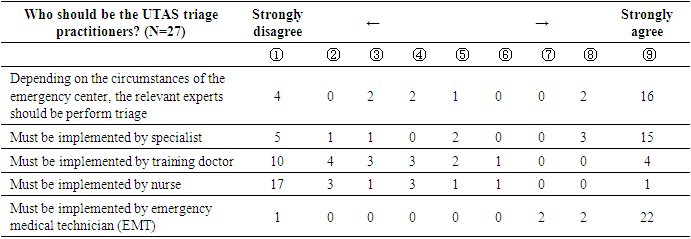

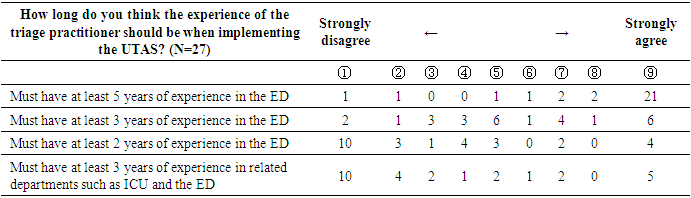

It was agreed that 92.6% of experts agreed on the sentence that triage practitioners must have at least 5 years of experience in the UTAS classification. Most experts agreed that the triage should be implemented by experienced medical personnel, so this should be considered in future operations.Table 12. Respondents' degree of agreement: Triage practitioners' experience

|

| |

|

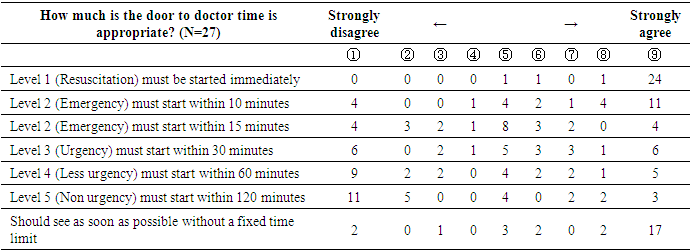

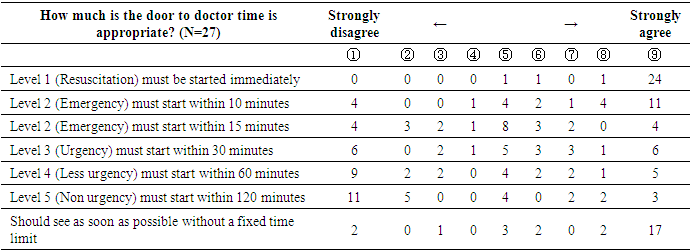

When operating the UTAS, the question was asked about “How much is the door to doctor (specialist) time appropriate?” It was agreed that 92.6% and 70.4% of experts agreed on the sentences of “Level 1 must be started immediately” and “Should see as soon as possible without a fixed time limit,’ respectively. On the other hand, no consensus was reached for patients below Level 2. It is believed that this is because most of the experts who have not operated the triage system are accustomed to seeing patients of any severity as quickly as possible. When introducing UTAS in the future, not only patients but also medical staff may feel a sense of resistance to waiting time. Education should be preceded that it is essential for patient safety and emergency department patient flow to treat the right patient at the right time. Table 13. Respondents' degree of agreement: Time limit of door to doctor time by level

|

| |

|

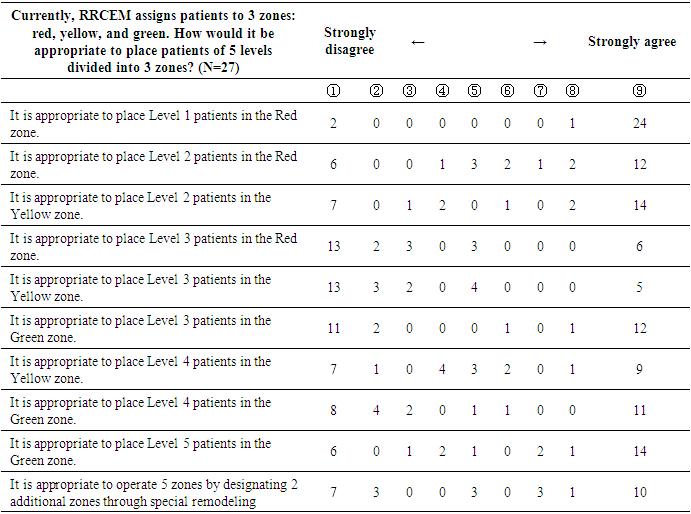

When using the UTAS, a 5-level triage system, how should patients be arranged to the 3 zones in the current RRCEM? 92.6% of experts agreed with the sentence “It is appropriate for Level 1 patients to be placed in the red zone”. On the other hand, it was agreed that 66.7% of experts disagree with the sentences that “Level 3 patients should be placed in the red zone” and “Level 3 patients should be placed in the yellow zone”. Level 3 patients are always an issue not only in CTAS but also in KTAS and JTAS. There are many cases in which a gap occurs in the reliability between triage practitioners or controversy on under- or over triage is also in most cases of Level 3 and 4 patients. Although the intention of this survey is about the special arrangement, it is expected that a lot of discussions will be needed on the classification and arrangement of Level 3 patients in the future.Table 14. Respondents' degree of agreement: Result of placement 5-level UTAS patients into 3 zones

|

| |

|

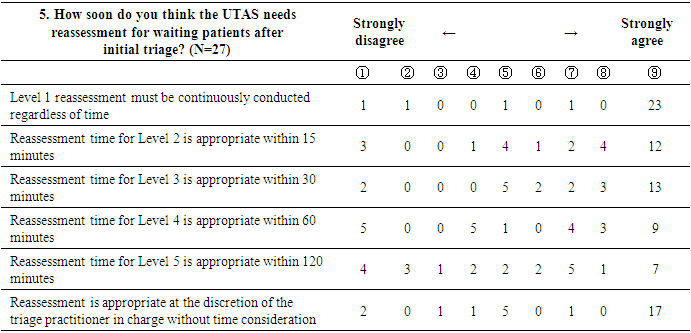

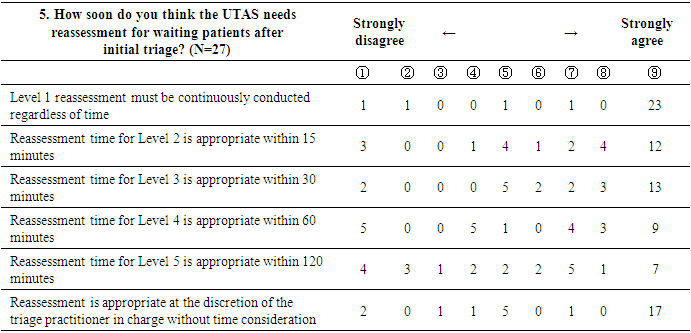

After the initial classification of the UTAS, it may be necessary to reassess the patients who are waiting before being seen by a specialist. Regarding the sentence about the reassessment time for each level, it was agreed that 88.9% of experts agreed on the item that “Level 1 reassessment must be continuously conducted regardless of time”. In addition, It was agreed that 66.7% of experts agreed on items “Reassessment time for Level 2 is appropriate within 15 minutes”, “Reassessment time for Level 3 is appropriate within 30 minutes”, and “Reassessment is appropriate at the discretion of the triage practitioner in charge without time consideration”.Table 15. Respondents' degree of agreement: Reassessment

|

| |

|

3. Conclusions

Uzbek experts seem to agree in principle with the implementation of the triage system. However, unlike other countries, experts agreed that it would be better to have experienced medical staff (e.g., specialists) in charge of triage practitioners. Most experts agreed that if 5-level UTAS is performed while maintaining the current 3 zones, Level 1 patients will be placed in the red zone. However, for Level 3 patients, there was a similar agreement that they should be placed in red or yellow zones. In future applications, the placement of these Leve 3 patients may be an issue. It seems appropriate to allocate Level 3 patients in the yellow zone under the condition that beds, equipment, and manpower in the yellow zone are strengthened. It has been found that most experts agree that a reassessment is required while waiting for a specialist’s consultation. However, in the case of patients with mild symptoms corresponding to level 4 and 5, no consensus was reached on the time limit for reassessment.

References

| [1] | Beveridge RC, Ducharme J: Emergency department triage and acuity: development of a national model (Canada) (abstract). Acad Emerg Med 1997; 4: 475-476. |

| [2] | Cape Triage Group. 2005. Cape triage score: hospital provider manual. Cape Town: joint Emergency Medicine Division - University of Cape Town & University of Stellenbosch. |

| [3] | Elshove-Bolk J, Mencl F, van Rijswijck BT, Simons MP, van Vugt AB. Validation of the Emergency Severity Index (ESI) in self-referred patients in a European emergency department. Emergency Medicine Journal. 2007; 24: 170-174. |

| [4] | Nestor, P. 2003. Triage history. [Online]. Available: journal of Emergency Primary Health Care, 1. P. 3-4. |

| [5] | Wuerz RC, Milne LW, Eitel DR, Travers D, Gilboy N. Reliability and validity of a new five-level triage instrument. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2000; 7: 236-242. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML