-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2021; 11(2): 117-121

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20211102.10

Received: Jan. 27, 2021; Accepted: Feb. 22, 2021; Published: Feb. 28, 2021

Prevalence of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus in 6 Regions of Uzbekistan

Atadjanova M. M.1, Ibragimova N. Sh.2, Akbarov Z. S.1, Alimov A. V.1

1Ya.Kh. Turakulov Tertiary Center for the Scientific and Clinical Study of Endocrinology, Uzbekistan Public Healthcare Ministry, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

2“Umid” Charity Public Association of the Disabled and People with Diabetes Mellitus, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

Correspondence to: Atadjanova M. M., Ya.Kh. Turakulov Tertiary Center for the Scientific and Clinical Study of Endocrinology, Uzbekistan Public Healthcare Ministry, Tashkent, Uzbekistan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2021 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

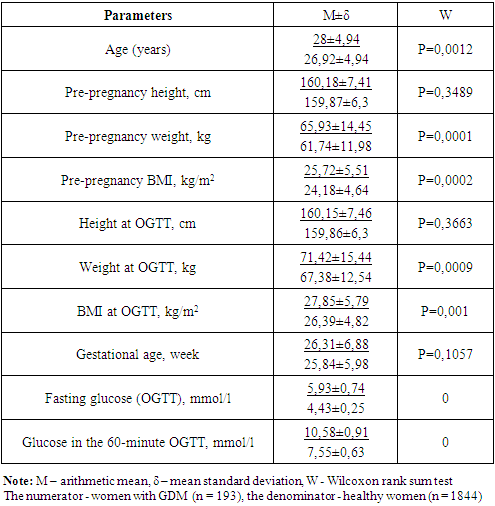

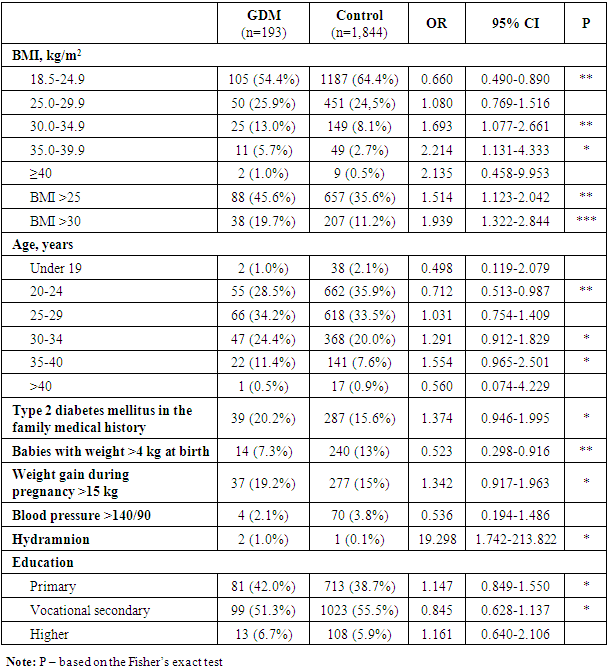

In 2019, the birth rate in Uzbekistan was up to 760 612 newborns. Detection of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is not yet supported by a local protocol for the management of pregnant women. Charity Public Association of the Disabled and People with Diabetes Mellitus, jointly with the Center of Endocrinology implemented “Strategy of the GDM prevention and monitoring in Uzbekistan” international project sponsored by the World Diabetes Foundation (2017-2020). Prior to the screening, a group of specialists conducted training sessions in all regions on GDM and on the methodology of screening for GP doctors, obstetrician-gynecologists (OG) and endocrinologists. Separately, training sessions were held for laboratory staff on the methodology of conducting oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT). Statistical data processing was performed by means of the IBM SPSS Statistics 23 program. Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to determine statistically significant differences in the quantitative parameters, Fisher’s exact test being used for the qualitative measurements. In six pilot regions, universal screening of GDM was carried out (with the help of OGTT). Gestational diabetes was diagnosed according to the International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups (IADPSG) criteria. 2037 pregnant women were examined. In 193 patients, GDM was identified (9.47%). Pregnant women with GDM were older (28 years vs. 26.9 years) and had a higher BMI both before pregnancy and during OGTT (25.72 vs. 24.18 kg / m2, and 27.85 vs. 26.39 kg/m2, respectively). The main risk factors for GDM were: age, overweight, burdened heredity for type 2 diabetes, and weight gain > 15 kg during pregnancy in the anamnesis.

Keywords: Gestational diabetes mellitus, Screening, Risk factors, Regions

Cite this paper: Atadjanova M. M., Ibragimova N. Sh., Akbarov Z. S., Alimov A. V., Prevalence of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus in 6 Regions of Uzbekistan, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 11 No. 2, 2021, pp. 117-121. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20211102.10.

- Gestational diabetes (GDM) is the most common medical complication of pregnancy. Since its prevalence is linked to the diabetes mellitus (DM) incidence in the population under study, and the DM prevalence tends to increase progressively, the GDM incidence grows accordingly. In addition, there are some tendencies favoring the growth in question, to name low physical activity and changes in eating habits due to accessibility of fast food, abundance of products with high glycemic index and carbonated soft drinks, as well as to increase of the expectant mothers’ age and spread of IVF (in vitro fertilization) programs. In most cases, GDM is asymptomatic requiring glucose tolerance test to be performed. In most countries, the GDM screening is mandatory and introduced in the pregnant women’s management standards [1-4]. It is problematic in countries where the GDM screening is not maintained by local protocols. This leads to the delayed diagnosis, maternal and fetal complications, urgent prescription of intense insulin therapy, urgent operative delivery, as well as to stresses for the expectant mother and her family. The GDM complications are well-known. Miscarriages, stillbirths, preeclampsia, hydramnion, preterm delivery and Cesarean section are among most common GDM maternal complications [5,6,7]; non-chromosomal congenital defects, infant respiratory distress syndrome, shoulder dystocia, macrosomia, diabetic fetopathy and neonatal hypoglycemia are those among fetal complications [7,8,9]. In addition to complications in pregnancy and delivery, long term complications, such as GDM in the next pregnancies, weight gain, as well as overt DM and cardio-vascular diseases are typical [10,11]. The long term complications, to name excessive weight or obesity in the childhood and adolescence [12,13], high blood pressure, insulin resistance and impaired glucose tolerance can be seen in the young ones [14,15]. Thus, early detection and treatment of GDM is the challenge from both medical and economical point of view.Until recently, despite high birth rate in Uzbekistan (760, 612 newborns in 2019), the GDM problem has remained unsolved. In compliance with the appropriate 2014 order issued by Uzbekistan Public Healthcare Ministry, a general practitioner should test glucose in the venous blood of a pregnant woman at the initial evaluation before the 12th week and repeatedly in 30 weeks of gestation. In actual practice, only the first of the tests is performed. Unfortunately, 100% coverage for glycemia in pregnant women cannot be performed, so there are no data on number of pregnant women with hyperglycemia in Uzbekistan. Effect of GDM on rise in frequency of complications in pregnancy and delivery, as well as long term consequences unfavorable for a mother and a baby taken into account, “Umid” (“Hope” from Uzbek), Charity Public Association of the Disabled and People with Diabetes Mellitus, jointly with the Center for the Scientific and Clinical Study of Endocrinology, Uzbekistan Public Healthcare Ministry, implemented “Strategy of the GDM prevention and monitoring in Uzbekistan” international project sponsored by the World Diabetes Foundation (2017-2020). Aim. The work was initiated to study the GDM prevalence in Uzbekistan and to identify the GDM key risk factors among Uzbek pregnant women by means of screening of pregnant women in 6 pilot regions of Uzbekistan.

1. Materials and Methods

- The universal screening of 2,037 pregnant women at 24-30 weeks of gestation for GDM was performed in 6 pilot regions of Uzbekistan. In Uzbekistan, there is a regional endocrinological dispensary in each region. Prior to the screening, a group of specialists from “Umid” Charity Public Association of the Disabled and People with Diabetes Mellitus and Ya.Kh. Turakulov Tertiary Center for the Scientific and Clinical Study of Endocrinology, Uzbekistan Public Healthcare Ministry, held training courses for general practitioners, obstetricians-gynecologists and endocrinologists on methods of screening, GDM etiology, pathogenesis, risk factors, clinical picture and diagnosis, as well as on treatment and post-partum management of women with GDM. For laboratory men, separate training courses on methods for the oral glucose tolerance test were held. In compliance with the order issued by Uzbekistan Healthcare Ministry, the staff workers of regional endocrinological dispensaries were to inform pregnant women beforehand about the future examination, its place and conditions. The enquiry and examination of pregnant women were conducted by a group of specialists from “Umid” Charity Public Association of the Disabled and People with Diabetes Mellitus and Ya.Kh. Turakulov Tertiary Center for the Scientific and Clinical Study of Endocrinology, Uzbekistan Public Healthcare Ministry, jointly with the accordingly instructed doctors and nurses at the regional dispensaries. The procedures for blood sampling and glycemia testing were performed by nurses and lab assistants from regional dispensaries under supervision of a lab assistant from the Center. Each woman was to have a questionnaire completed with her passport data as well as details of her education, work place and position, last menstrual period and date of registration for pregnancy, number and outcomes of previous pregnancies, type and time of deliveries, GDM risk factors including diabetes mellitus in the family medical history, macrosomic baby, miscarriages, stillbirths, babies with congenital disorders, weight gain > 15kg during previous pregnancies, elevations of blood glucose in medical history, age > 30 years and BMI > 25 kg/m2 by the onset of pregnancy and arterial hypertension in medical history. All women had their height and weight, arterial pressure, fasting glucose and in 60 minutes after 75g-glucose load measured; fetal ECG and ultrasonography were performed. All women gave their consent for participation in the study. Before the study, training workshops were held to standardize the anthropometric and clinical measurements. The height was measured by means of a conventional height meter, the weight being measured with the electronic floor scales (Tefal PP1140V0 Classic Blossom, China). Sitting arterial blood pressure was measured twice by means of the calibrated sphygmomanometer (KD Medical GmbH Hospital Products, Germany) after 5-10-minute rest with the mean value taken into account. The values of pre-pregnancy weight and weight at the primary examination were taken from the patient’s medical history. Weight gain by the OGTT was calculated as the difference between the initial weight and the one measured at examination. Body mass index was calculated as the body mass in kg divided by the square of the body height. Body mass excess and obesity were determined using the reference data for Uzbek women [16] coinciding with the WHO criteria for the Caucasians, that is, normal BMI ranging from 18 to 24.9 kg/m2, excessive BMI ranging from 25.0 to 29.9 kg/m2 and obesity-typical BMI > 30.0 kg/m2. Gestational diabetes mellitus was diagnosed in accordance with the International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups (IADPSG) recommendations on the diagnosis of GDM [17]. According to the recommendations of the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO), all countries should provide the best GDM management by given available resources and social status of the country and population under study [5]. In our study, the two-hour diagnostic procedure for GDM turned out infeasible due to failure of most women to stay for two and more hours.Statistical data processing was performed by means of the IBM SPSS Statistics 23 program. Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to determine statistically significant differences in the quantitative parameters, Fisher’s exact test being used for the qualitative measurements. Inter-group differences were considered significant at p<0.05. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95%CI were calculated. A method for standardization of intensive parameters by Shigan E.N., based on Bayesian probability was used. After examination, the questionnaires completed by the participants were entered into the database at the Ya.Kh. Turakulov Tertiary Center for the Scientific and Clinical Study of Endocrinology, to be processed. Pregnant women with GDM were referred under supervision of endocrinologists at the regional endocrinological dispensaries and of obstetrician-gynecologists at the out-patient clinic.

2. Results

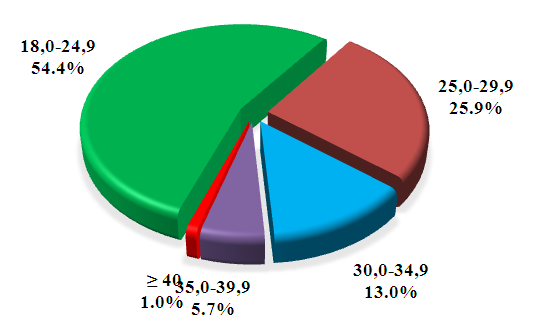

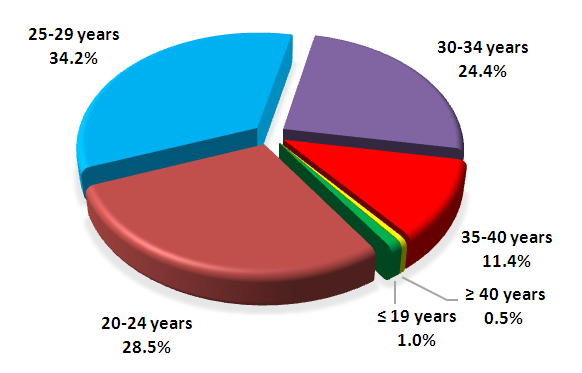

- A total of 2,307 pregnant women at 24-30 weeks of pregnancies were examined; 193 of them had GDM (Table 1). There were no carbohydrate metabolism disorders in 1,844 pregnant women who were included into the control group. Those with GDM were older than the healthy women (mean age 28 versus 26.9 years). The women with GDM had higher BMI both prior to pregnancy and at the oral glucose tolerance test (25.72 and 27.85 kg/m2). The BMI values in the patients in the control group were 24.18 kg/m2 and 26.39 kg/m2 prior to pregnancy and at the examination, respectively. The gestational ages were almost similar in both groups, 26.31 and 25.84 weeks in women with and without GDM, respectively.

|

| Figure 1. Distribution of women with GDM by BMI |

| Figure 2. Аge of women with GDM |

|

3. Discussion

- The first-ever screening of GDM among pregnant women at 24-30 week of gestation demonstrated the GDM prevalence in 6 regions of Uzbekistan to be 9.47%. Our findings are in line with those of other authors studying the GDM prevalence in the Asian countries. According to Lee et al., the pooled GDM prevalence in Asia was 11.5% (95%CI 10.9-12.1) [18]. The authors carried out a meta-analysis including 84 studies from 20 countries across Asia, to name India, China, South Korea, Iran, Pakistan, Turkmenistan and others. Among the countries using a one- or two-step screening procedures with different diagnostic criteria and methods of testing, the prevalence of GDM was highest in Taiwan (38.5%). The lowest prevalence of GDM was found in Nepal (1.5%).Turkmenistan is the only Central Asian country with the identified GDM prevalence, which is 6.3% [19]. In the study carried out by Parhofer et al. by the two-step screening procedure at the perinatal center in Ashgabat, age, BMI, parity and blood pressure were found to associate with GDM [19]. Our findings are in line with theirs, but as in our study arterial hypertension was found only in 4 of 193 patients (2.3%), and most women had no idea of their normal blood pressure, arterial hypertension was of low value. The same holds for the family history of diabetes mellitus. The point is that many diabetics in Uzbekistan are unaware of their condition, so the factor turned out underestimated. According to findings from screening of type 2 diabetes mellitus among people older than 35 years in Uzbekistan, its prevalence in 2015-2016 was 7.9% [20], while there were only 169,000 (0.8%) people with diabetes registered at the regional endocrine dispensaries. The prevalence of GDM in Iran was estimated to be 7.5% [21], significantly increasing with the raising of a mother’s age and her BMI, as well as with presence of GDM in prior pregnancies and macrosomic baby. In a large study on GDM in 15 hospitals of Peking the GDM prevalence was estimated to be 19.7%. Age, pre-pregnancy BMI, excessive weight gain before 24 weeks of gestation and diabetes mellitus in the family history were found to be the key GDM risk factors. Our findings are consistent with those of other authors studying GDM in the Asian populations. Similarly, Lee et al. [18] demonstrated association of GDM with parity ≥ 2, GDM in medical history, congenital disorders, stillbirths, abortions, preterm delivery, macrosomic baby, gestational hypertension, age ≥ 25 years, BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 and diabetes mellitus in the family history. According to the criteria of Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group in India (DIPSI), the GDM prevalence in India ranged from 3.8 to 17.9%, in some provinces measuring up to 35% (WHO/IADPSG criteria) [22]. According to meta-analysis of studies carried out in Turkey on the prevalence of GDM over the period 2004-2016, it was 7.7% ranging from 3.5 to 22.3% by diagnostic criteria, region and methods of testing [23]. The advanced maternal age, excessive weight prior to pregnancy, weight gain in pregnancy, diabetes in the family, GDM and a large baby at birth in medical history, as well as week gestational age, number of pregnancies, deliveries, abortions and stillbirths were among the most common GDM risk factors [23]. All this is in the line with our findings on the GDM risk factors. The findings from our first-ever study demonstrated the GDM prevalence in 6 pilot regions of Uzbekistan to be 9.47%. The age, body mass index (BMI) measured at the oral glucose tolerance test, parity, BMI prior to pregnancy, preeclampsia, arterial hypertension, stillbirths and miscarriages in medical history, as well as diabetes mellitus in family history and weight gain more than 15 kg in prior pregnancies were found to be most significant risk factors among pregnant women in the regions under study. High birthrate and high GDM incidence among pregnant women in Uzbekistan highlight the need for the GDM diagnosis to be included in the standards of medical care for pregnant women to prevent complications of gestation and delivery, as well as long term health consequences in a mother and a child.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML