-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2020; 10(6): 422-429

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20201006.15

Depression in Patients with Epilepsy is Influenced by the Duration of Epilepsy

Fawzi Babtain 1, Mohammed Alqahtani 2, 3, Dlaim Alqahtani 4, Faisal Al Malwi 2, Muhannad Asiri 3, Harsha Bhatia 4, Muthusamy Velmurugan 4

1Division of Neurology, King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

2Armed Forces Hospitals-Southern Region, Khamis Mushait, Saudi Arabia

3King Fahad Hospital-Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

4Division of Neurology, Aseer Central Hospital, Abha, Saudi Arabia

Correspondence to: Fawzi Babtain , Division of Neurology, King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Depression is the most common psychiatric disease seen in patients with epilepsy, with a higher incidence of suicide, yet the onset of depression in these patients is not known for which this study will aim to evaluate the association between depression and epilepsy duration. In this cross-sectional study, patients seen within five years from the diagnosis of epilepsy were divided into two groups; newly diagnosed patients with epilepsy (diagnosed within one year) and those diagnosed between 1-5 years. Beck Depression Inventory (DB – II) was used to screen and classify the severity of depression. Newly diagnosed patients had a significantly higher DB- II scale compared to those diagnosed between 1 – 5 years (an average of the scale of 19.6 vs. 14.8 respectively, 95% CI; 0.27- 9.2, p value = 0.04). Depression scale was also significantly higher in those lacking family history of epilepsy (FH) (1.1 higher, p=0.01, 95% CI; 0.1,3.6). Newly diagnosed patients with epilepsy were also three times more likely to have depression compared to the other group (the adjusted OR = 3.1, 95% CI; 1.2 – 8.3, p = 0.02). The study findings suggested the need to promptly screen for depression in epileptic patients, particularly at an earlier course of the disease. The significant association between epilepsy duration and depression could be related to the difficult adjustment they experienced following the diagnosis of epilepsy, especially in patients lacking the family history of epilepsy.

Keywords: Epilepsy, Depression, Family History of Epilepsy (FH)

Cite this paper: Fawzi Babtain , Mohammed Alqahtani , Dlaim Alqahtani , Faisal Al Malwi , Muhannad Asiri , Harsha Bhatia , Muthusamy Velmurugan , Depression in Patients with Epilepsy is Influenced by the Duration of Epilepsy, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 10 No. 6, 2020, pp. 422-429. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20201006.15.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Epilepsy is one of the most common neurological disorders affecting patients of all ages, with a worldwide prevalence of 7.1 per 1000 persons [1,2]. In someone's life, the risk of developing epilepsy is about 1 in 26 [3]. It is known to be caused by different etiologies that may vary according to age and could have psychological and cognitive components [4]. Both men and women of all ages could be affected by epilepsy. It contributes to 0.75 % of the burden of disease, based on disability-adjusted life years [5], which is defined as " years of productivity lost as a result of disability or premature death." Epilepsy classifications were revised more recently to focus on the associated co-morbidities and the consideration of gender issues [6]. The reported psychiatric symptoms in epileptic patients are usually seen during the different stages of the seizure (i.e., pre-ictal, ictal and post-ictal phases), which can be primarily explained by the seizure onset zone, defined as the "area of the cortex from which clinical seizures are generated" [7]. However, this zone is not always determined in patients with localization-related epilepsy.Psychological co-morbidities, namely anxiety and depression, were known to be associated with epilepsy, with a variable prevalence [8,9]. Depression was reported in up to 80% of these patients, which was associated with a higher incidence of suicide that would add to the pre-existing risk of suicide-related to anti-epileptics use [10,11]. An interesting observation was the increased risk of epilepsy in patients with major depression, which may suggest an interaction between depression and epilepsy not related to the side effect of epilepsy treatment [11,12]. The evidence mentioned above urge clinicians, and neurologists, in particular, to identify psychiatric co-morbidities in these patients, since the later can go undiagnosed for many reasons including lack of knowledge or awareness of these symptoms, but also difficulties in accessing mental health professionals, all of which may negatively affect epilepsy, seizure control and ultimately the quality of life of these cases [13,14]. In this cross-sectional study, we aimed to evaluate any association between the presence of depression and the duration of epilepsy in patients diagnosed within five years.

2. Materials and Method

- This is a cross-sectional study of patients with epilepsy evaluated in Aseer central hospital, Abha, Saudi Arabia. Our hospital is the regional hospital of the city, with a capture area of around 1.9 million people, a hospital affiliated with the college of medicine, King Khalid University.

2.1. Subjects

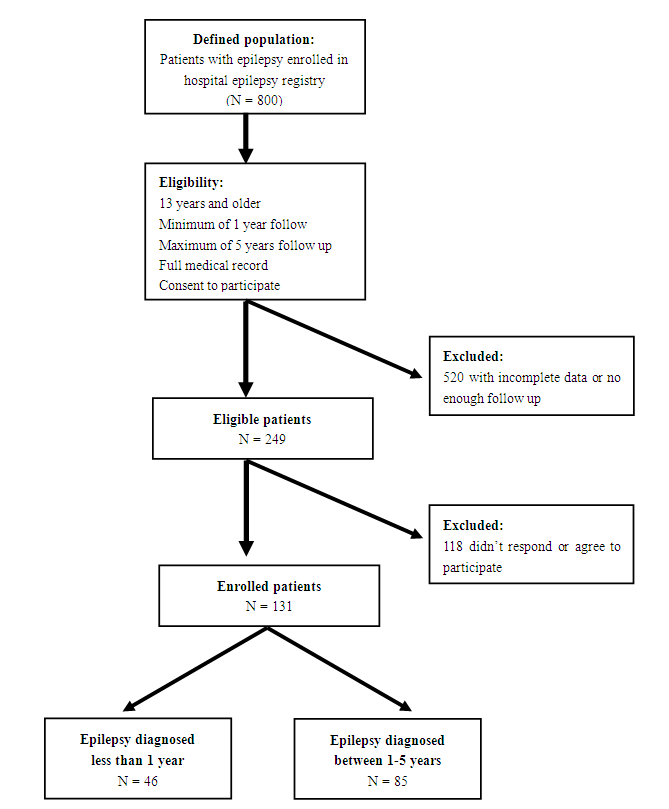

- Data on patients with epilepsy were collected using the hospital's epilepsy registry that started in 2009, which included about 800 patients 13 years and older, as of December 2015. The registry included data on patient's age, age at the first seizure, sex, epilepsy classification according to etiology and seizure semiology, electroencephalogram (EEG), magnetic resonance image (MRI) of the brain findings, and epilepsy risk factors, including a family history of epilepsy and history of parental consanguinity. The registry also included treatment regimens, and whether the patient is seizure-free or not. Full details of the registry were previously described [15]. Patients to be included in this study should also have complete clinical records, as well as the data on surface electroencephalogram (EEG) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain, to classify their epilepsy adequately and identify a possible etiology. Patients also should have a follow up between one year and five years to analyze the association between the duration of epilepsy and depression. Patient should provide a verbal consent to participate in the study (figure 1- study flow chart). EEG interpretation was provided by an epileptologist, while a radiologist provided reports on the MRI of the brain. The International Classification of Seizures and Epilepsies (ICES) was used to classified epilepsy, according to etiology (idiopathic, cryptogenic, and symptomatic) [16]. Idiopathic epilepsy was considered to be the underlying etiology if no structural brain lesion or other neurologic signs or symptoms were identified, and the underlying cause was presumed to be genetic. Probably symptomatic or cryptogenic epilepsy was considered when no identified etiology was found, but the cause is believed to be an unrecognized underlying etiology. Finally, symptomatic epilepsy is considered when a structural brain lesion or a metabolic disturbance was identified and found to cause the seizures [17,18].

| Figure 1. Flow chart of the study design |

2.2. Epilepsy Duration

- To identify the prevalence of depression at earlier stages of epilepsy, patients diagnosed in the last five years were considered for this study. Furthermore, patients were considered to be newly diagnosed if they had two or more unprovoked seizures within 12 months of the diagnosis, a definition similar to what was reported in the literature [19], while patients diagnosed more than one year but up to 5 years were considered to have the old diagnosis of epilepsy.

2.3. Identifying Depression

- Screening for depression was conducted using Beck Depression Inventory (BDI – II) [20], a ten minutes self- administered, or verbally by an administrator, provided in Arabic, with 81% sensitivity and 92% specificity, which highly correlated with other validated Depression scale, with a high reliability and not overly sensitive to daily mood changes [21]. BDI was also valuable to scale depression into mild, moderate, and severe. In order to run the scale, eligible patients were contacted in e-mails phone calls, or e-mails with a secured link to an electronic version of BDI-II e-mailed be answered and e-mailed back to investigators. Verbal consent was obtained from all eligible patients before conducting the study.

2.4. Data Analysis

- Contingency tables and Fisher exact were used to calculate X2 for categorical data, and Student's t-test was used for continuous variables. The 95% confidence intervals (CI) were determined, and the p value of ≤ 0.05 was used to indicate how compatible the data were with the statistical method used, in accordance with the American Statistical association statement [23]. The odds ratio (OR) was calculated, and regression analysis (multiple linear and logistic regressions) were used accordingly to estimate the effect on the depression scale, and to predict depression. One sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test for normality of the depression scale was performed. Since depression scale data were skewed slightly to the right, a transformation of this data was performed, where the quadratic method was used for the linear regression model; i.e. the squared root of depression scale was the dependent variable. Pairwise bivariate data analysis was done prior to building the final regression model, in order to identify collinearity between variables, which could help in building the final regression model of both the linear and logistic analyses. A descriptive comparative method was performed to provide basic descriptive analysis and prevalence, but the analytical method was also performed to performed by different regression analyses. Statistical analysis was performed using R for Macintosh: A language and environment for statistical computing, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL http://www.R-project.org/.

3. Results

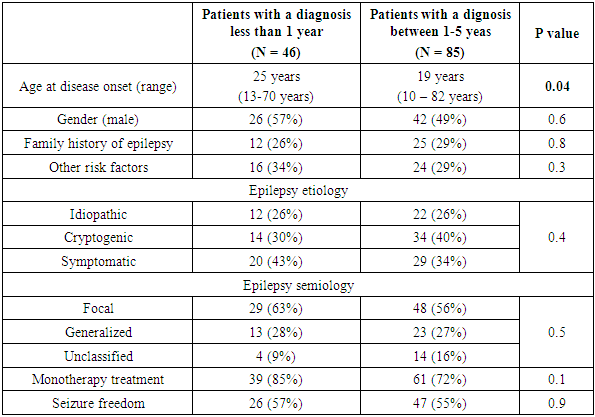

- A total of 249 patients in our epilepsy registry were eligible for the study, including 113 patients (41%) diagnosed within 12 months, and 136 patients (63%) diagnosed between 1 - 5 years, but only 131 patients responded and participated in the study. There were 68 men (52%), with the mean age was 24 years (range; 13-82 years), and the mean age at disease onset was 16 years (range; 12-80 years). Epilepsy was classified as idiopathic in 34 cases (26%), cryptogenic in 48 cases (36%), and symptomatic in 49 cases (37%). Based on seizure semiology, 77 patients (59%) had focal epilepsy, the most common localization related epilepsy in adults [24], 36 patients (27%) had generalized epilepsy, and in only 18 patients (14%), we failed to identify seizure onset zone despite the clinical, radiological and electrographic data available, for which epilepsy in those patients was considered unclassified. Based on the distribution of seizure etiology, semiology, along with the wide range of ages, our studied population represented a sample with characteristics similar to the population, with no over-representation of a particular seizure semiology or etiology. Among the studied patients, 46 patients (35%) were considered newly diagnosed and 85 patients (65%) had the diagnosis of epilepsy between 1-5 years (Table 1).

|

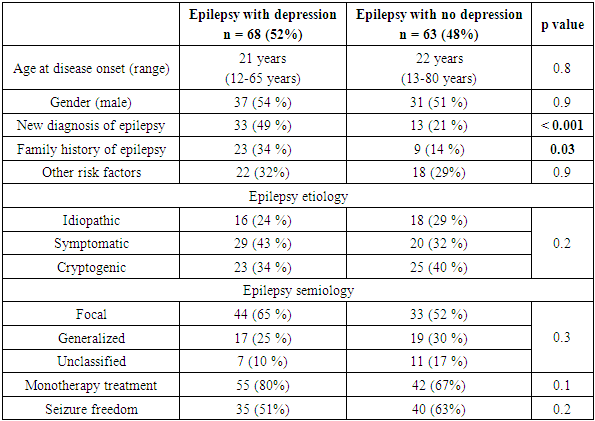

3.1. Depression and Duration of Epilepsy

- According to BDI- II, 68 patients (52%) were found to have depression. Table 2 showed patients’ characteristics according to the presence or absence of depression. Patients who were diagnosed with epilepsy within a year were about three times more likely to have depression compared to those who had the diagnosis of epilepsy from 1 - 5 years (72 vs 41%, the unadjusted OR = 3.63, 95% CI; 1.67 - 7.86, p value < 0.001). Therefore, the crude odds indicated a strong association between depression and the duration of epilepsy.

|

3.2. The Severity of Depression and the Duration of Epilepsy

- The severity of depression was also determined for our group, using BDI – II. In this scale, a score from 0 - 9 is considered normal, 10 -18 is mild depression, 19 - 29 is moderate depression, and a score of more than 29 indicates a severe depression [20]. Twenty-three patients (34%) had mild depression, 24 patients (35%) had moderate depression, and severe depression was found in 21 patients (31%). The mean scale was 4.7 points higher in patients diagnosed with epilepsy within a year compared to those with the diagnosis from 1-5 years (the mean BDI – II score of 19.6 and 14.8 respectively, 95% CI; 0.27- 9.2, p value = 0.04). This observation put those diagnosed within a year at the range of moderate depression, while the other group's scale fell well within the mild depression, for which one can conclude that newly diagnosed patients were not only more likely to be depressed but also a slightly had more advanced stages of depression. Depression scale did not differ between sexes (p = 0.8), or epilepsy etiologies (p = 0.9) or semiologies (p = 0.2).

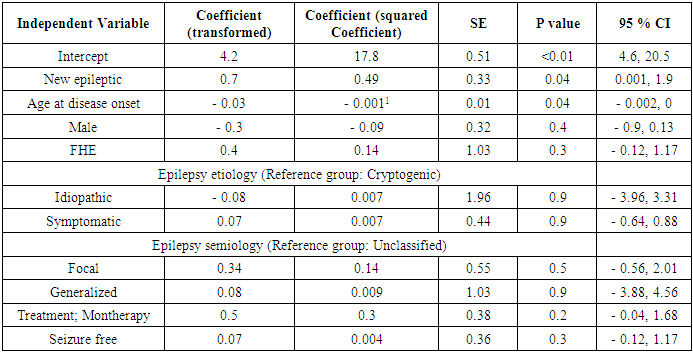

3.3. Depression Scale and the Duration of Epilepsy

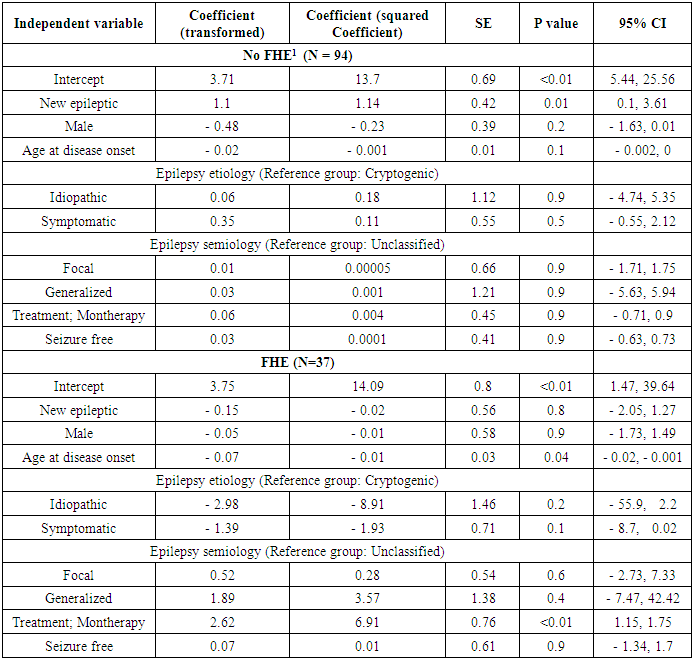

- One sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test for normality of the depression scale was performed, confirming a non-normal distribution of the data (p = 0.004). To further estimate the effect of duration of epilepsy, along with other relevant factors, on the depression scale, multiple linear regression analysis was done, using the transformed depression scale as the dependent variable, and duration of epilepsy as the independent variable, adjusted for age at the diagnosis of epilepsy, gender, and epilepsy semiology and etiology. Pairwise analysis of variables prior to building the regression model showed high correlations between epilepsy etiology and semiology (table 1). Still, because both variables were crucial in understanding the association between depression and epilepsy duration, both variables were used in the final model, which was built using a stepwise approach (Table 3). On average, the mean depression scale was about half a point higher in newly diagnosed epileptics (0.6, 95% CI; 0.01 – 2.1, p value = 0.02). Similarly, for each increase in the age at the time of the diagnosis by 10 years, the depression scale will decrease by only 0.1 (95% CI, 0.002 - 0.25, p value = 0.02). Despite the statistically significant result, it may not have a measurable clinical effect. The regression model only explained 8% of the variability of BD I- II scale (R2 = 0.10). Because of the possibility of difficult adjustment to the diagnosis of epilepsy, subgroup analysis according to the presence or absence of FHE was conducted to estimate the effect of the duration of epilepsy on depression scale (table 4). Only in patients lacking FHE, the mean DBI –II scale was significantly higher in newly diagnosed patients compared to the other group (1.14, 95% CI; 0.1, 3.61, p = 0.01), a higher mean of the scale compared to mean of the whole group, and the association between the depression scale and duration of epilepsy was not observed in patients who had FHE (- 0.02, 95% CI; - 2.05, 1.27, p = 0.8). The marked changes in DBI – II scale based on the presence or absence of FHE indicated a different impact of epilepsy duration on depression according to these circumstances. The variables used in the final multiple regression model (table 3) failed to contribute individually to the effect of duration of epilepsy on depression scale, when used separately, as a covariant, in analysis covariant (ANCOVA), with the exception of FHE (F statistic=3.5, p < 0.05).

|

|

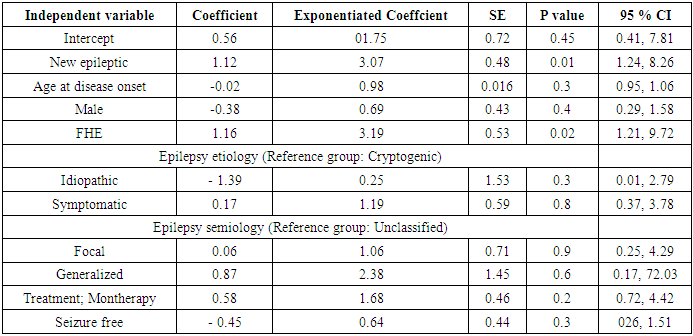

3.4. The odds of Depression in Epileptic Patients

- The adjusted odds of depression among our studied population was estimated using logistic regression analysis. The presence or absence of depression was the dependent variable, while the duration of epilepsy (new vs old) was the independent variable adjusted for age at the time of diagnosis, gender, epilepsy semiology, etiology, the presence of a family history of epilepsy, and treatment regimen (table 5). Our newly diagnosed patients with epilepsy had 3 times the odds of being depressed compared to patients diagnosed with epilepsy between 1- 5 years (OR = 3.1, 95% CI; 1.2 – 8.3, p = 0.02). There were no other effect modification terms noted in the regression model.

|

4. Discussion

- Depression is seen in up to 20% of the general population [24] and considered the most common psychiatric comorbidities seen in epileptic patients. It is one of the most frequently reported psychiatric disorders in these patients [25]. In a recent meta-analysis, the prevalence of depression among patients with epilepsy was estimated to reach 23% [26]. Suicide, as a consequence of depression, is the most common cause of death in these patients [27]. Depression itself affected the quality of life in epileptic patients more than epilepsy or anti-epileptics together [28], even in those patients who achieved the seizure-free state, which is the ultimate goal to reach in all epileptic patients [29,30]. Yet, depression was more likely to be reported in patients with uncontrolled seizures [31]. This evidence highlighted the negative impact of depression on epilepsy and the quality of life of the affected patients.More than half of our patients were depressed; at least two-thirds of them had a moderate to severe depression. These findings, although somehow worrisome, should bring more attention to recognize depression in patients with epilepsy. Furthermore, patients who were diagnosed within a year were 3 - 4 times more likely to be depressed, even when adjusted for other factors that may affect the risk of depression in these patients. The newly diagnosed patients also had a slightly advanced depression scale compared to the patients who were diagnosed for more than a year. The higher prevalence and probably the severity of depression in newly diagnosed epileptics can be explained by the fact that these patients had difficulties adapting to seizures and being epileptic, following the diagnosis of epilepsy, for which reactive depression was the way to show their initial adaptation to these changes. On the other hand, patients diagnosed more than a year probably coped better with epilepsy over the longer period they lived with epilepsy. We didn't have any information on whether the latter group had depression or not earlier after the diagnosis since we don't formally conduct depression surveys in these patients at the time of the diagnosis, or with subsequent follow-up, yet it's intuitive to assume the likelihood of depression in a considerable proportion of them based on our current study. It's very crucial, therefore, to pay more attention to depression in patients with epilepsy, particularly in those with the recent diagnosis. Our study demonstrated new findings of the temporal association between depression and duration of epilepsy, which should initiate a rather aggressive and more serious consideration of depression early in the disease course. More attention should be directed towards patients who had a positive family history of epilepsy to be screened for depression. Furthermore, using any reliable screening tool for depression is a non-expensive diagnostic tool that could potentially minimize a burden on the healthcare system, by treating depression, probably at an advanced stage, along with the pre-existing financial burden epilepsy has on the healthcare system. It’s prudent to include screening for depression as a basic assessment of newly diagnosed patients with epilepsy, and also to maintain a vigilant observation for depression throughout the disease course.Since our study was observational, selection bias was the most important bias that can threaten the validity of our results. Eligible patients were selected for the study based on predetermined criteria, to include all patients diagnosed with epilepsy for the last five years. We got a positive response from 53% of the eligible patients for different reasons that included difficulty reaching some of them, incomplete or inaccessible medical records, and voluntary refusal to participate in the study. Yet, the proportion of patients with the new and old diagnosis of epilepsy didn't change. The studied patients had the distribution of epilepsy etiology and semiology similar to the general population, which suggested a representative sample of the defined population, and selection bias was unlikely.Our study had some limitations. Because of the study design, we could not identify the direction of the association between depression and the duration of epilepsy. We couldn't also determine how early depression occurred after the diagnosis of epilepsy. A prospective cohort study can answer both questions, although it is logical to think of depression been secondary to epilepsy. Finally, since we didn't have a baseline screening for depression in our practice, we couldn't identify patients with pre-existing depression that would contribute to its prevalence in our studied group. Depression is neither a routine baseline nor a follow-up screening measure used in most of epilepsy practice, but our findings suggest the need to screen for depression in epileptic patients, especially in those with the recent diagnosis.

5. Conclusions

- Depression is a common psychiatric co-morbidity reported in epileptic patients. Its prevalence, and probably severity are associated with epilepsy duration, since newly diagnosed epileptics within a year were more likely to have depression, at slightly advanced stages of the disease. Earlier screening for depression, along with other basic epilepsy investigation and management, as well as throughout the disease course, is recommended in these patients to improve patient’s quality of life and reduce the disease burden.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML