Nishanov F. N., Nishanov M. F., Egamov S. Sh., Mamarasulov M. K., Robbidinov B. S.

Andijan State Medical Institute, Uzbekistan

Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Abstract

The aim of the study was to search for effective hemostasis of pyloroduodenal ulcers without surgical interventions. It would delay the operation to the stage of elective surgery, and to avoid it in number of patients. Material. The authors conducted treatment analysis of 674 patients admitted to the emergency surgery department with gastric and duodenal ulcer complicated by bleeding from 2001 to 2016. Methods. The authors developed an algorithm of diagnostic and treatment tactics for ulcerative pyloroduodenal bleeding. Results. The hemorrhage recurrence in the group of non-operated patients decreased from 7.7% (relapse was noted in 17 cases of 221) to 2.7% (in 9 patients of 329) (χ2 = 6.504; df = 1; p = 0.011) and the need for surgical treatment decreased from 30.6% (in 90 from 294 patients) to 15.8% (in 60 of 380 patients) (χ2 = 21.049; df = 2; p <0.001). Conclusion. The use of complex developed preventive measures has significantly improved the treatment results and reduced surgical interventions.

Keywords:

Stomach, Duodenum, Bleeding, Hemostasis, Endoscopy, Pharmacotherapy

Cite this paper: Nishanov F. N., Nishanov M. F., Egamov S. Sh., Mamarasulov M. K., Robbidinov B. S., Optimization of Treatment Tactics of Bleeding Gastric and Duodenal Ulcers, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 10 No. 2, 2020, pp. 106-111. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20201002.07.

1. Introduction

Bleeding is the most serious complication of duodenal ulcer. Patients of this category make up 18% -23% among ones with seven forms of “acute abdomen” and take the third place in their structure. There has been a clear trend towards an increase in the frequency of this complication in recent years. At the same time, the proportion of elderly and senile patients and patients hospitalized after 24 hours from the onset of this complication is growing [1-4]. The reasons of the increase in the number of patients are the lack of dispensary monitoring for patients with peptic ulcer disease, a decrease in the availability of medical care, an increase in the cost of medical services and drugs, a decrease in the number of elective surgeries [5-7]. In spite of improvements in non-surgical methods, such as the use of proton pump inhibitors and therapeutic endoscopy, surgery for ulcerative bleeding remains routine. Such surgeries are performed in 10% -20% of patients hospitalized due to hemorrhage in the upper part of gastrointestinal tract (GIT) [8-9]. Literary data testify that bleeding mostly occurs with age [10]. Thus, the mortality rate after ulcerative bleeding remained at about 10%. The need to improve surgical treatment methods in this group is an important issue of modern surgery. In a large prospective study conducted by the American Society of GIT Endoscopy (Oakbrook, Ill), 347 (15.6%) of 2225 patients with bleeding ulcers needed surgery [10-11]. Further studies at the University of California, Irvine showed that 19% of patients undergoing therapeutic endoscopy for ulcerative bleeding need surgery. It is important to note that surgical intervention was urgently or urgently needed in 70% and 100% of patients requiring surgery. D. Troland et al. (2018), in response to the question of the importance of therapeutic endoscopy in eliminating the need for surgical intervention and whether it should be examined more than once, conducted a prospective study. Approximately one third of the 3.500 patients admitted to the hospital with bleeding peptic ulcers underwent therapeutic endoscopy over a 4-year period. Seventeen patients (1.5%) turned directly to surgery after an unsuccessful primary endoscopic control. Bleeding recurred in 100 patients or 8.7% of the entire population. The median blood transfusion in this last group was 5 units, which indicates significant bleeding. 27% of the 48 patients randomized for re-endoscopy underwent failed endoscopy and needed emergency surgery with a 46% incidence of postoperative complications [12].The emergence of new endoscopic technologies and highly effective anti-ulcer drugs necessitates an assessment of their capabilities in the treatment of a bleeding duodenal ulcer. This is especially true in connection with the increase in the proportion of elderly patients who are contraindicated in traumatic surgery [13-15].Aim of the study is to improve treatment results in patients with bleeding duodenal and gastric ulcers which would delay the operation to the stage of elective surgery, and to avoid it in a number of patients.

2. Material and Methods

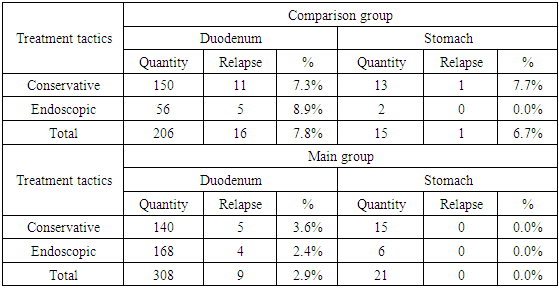

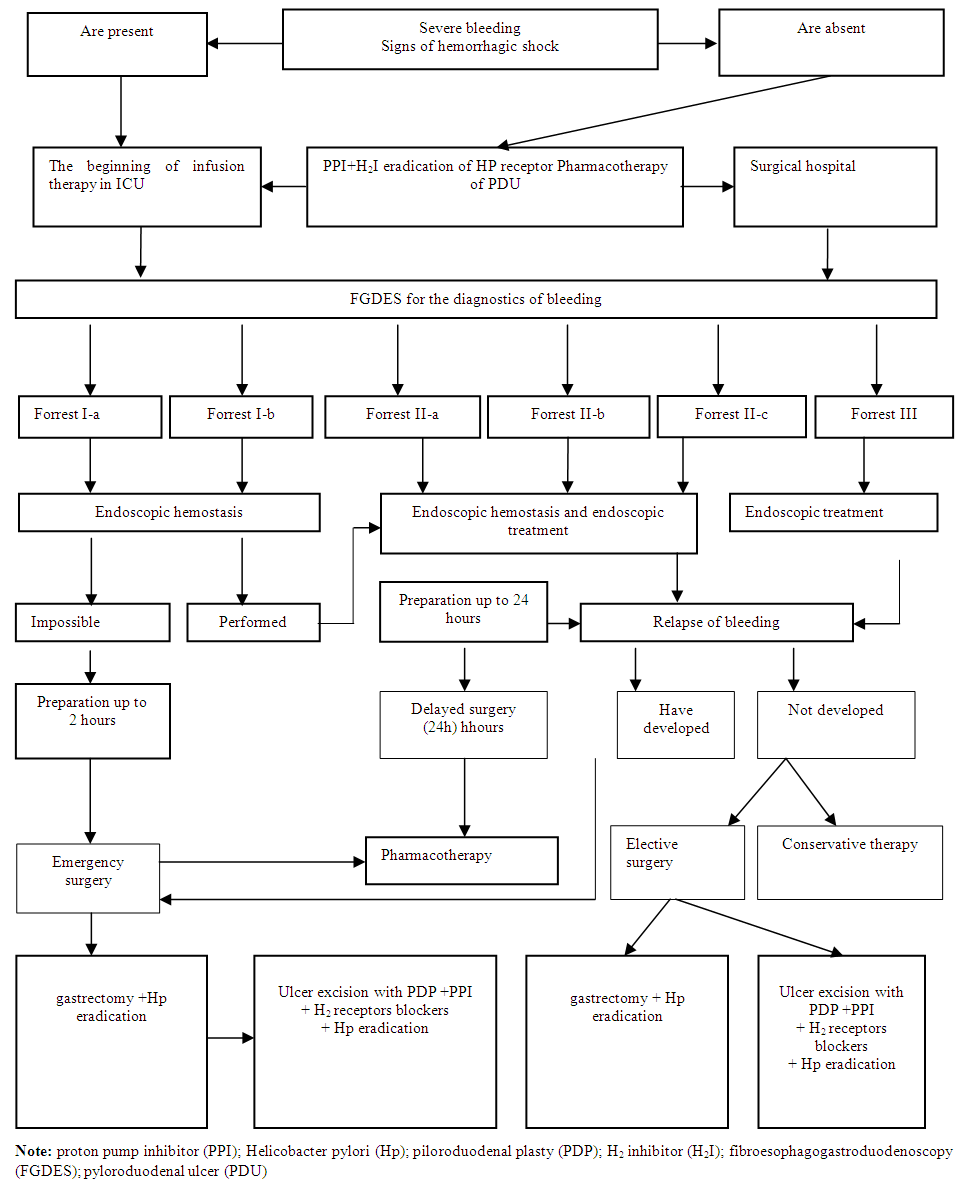

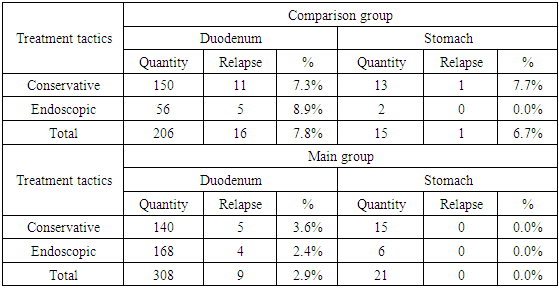

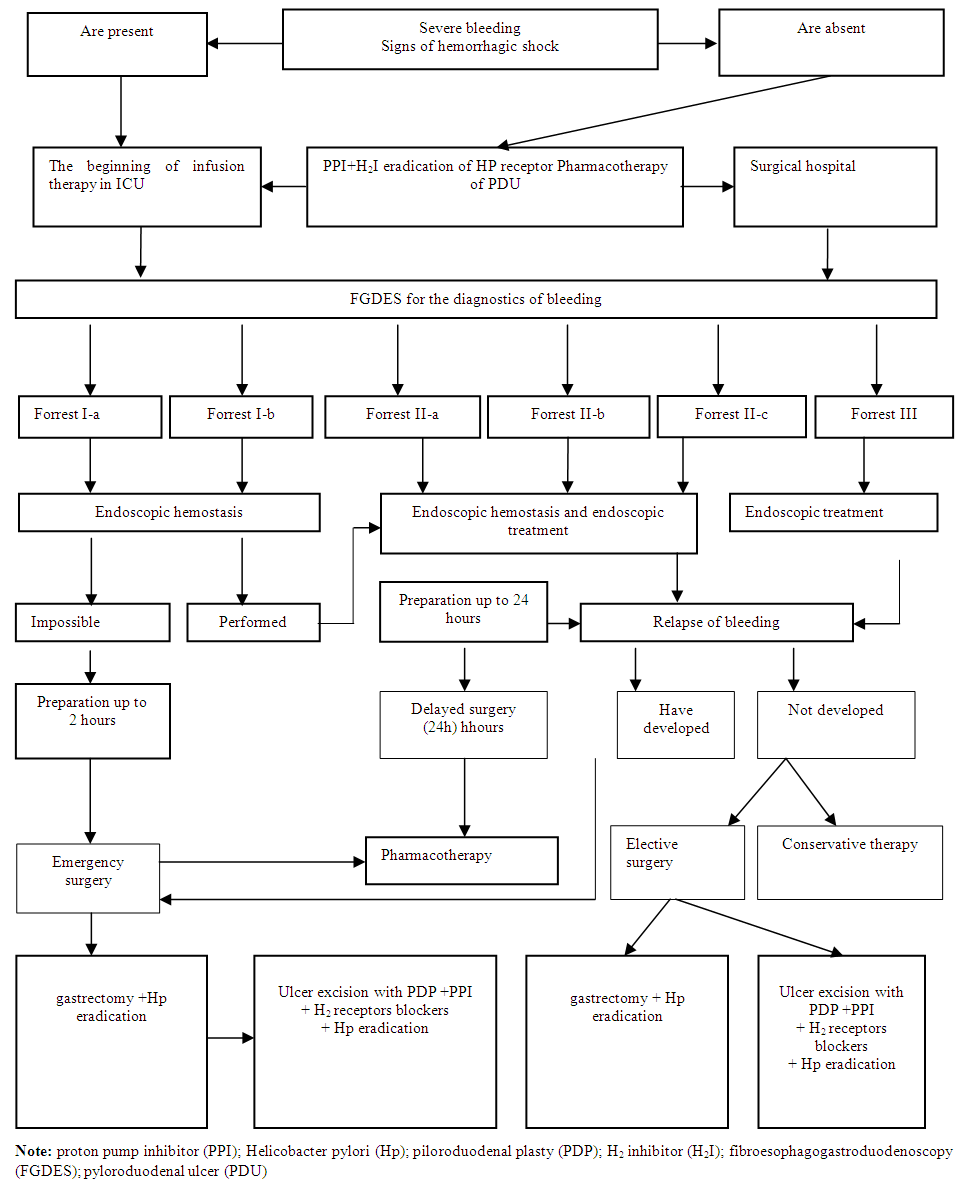

This study is based on the analysis of treatment results in 674 patients with gastric and duodenal ulcer complicated by bleeding admitted to the emergency surgery department from 2001 to 2016.We have developed an algorithm for therapeutic and diagnostic tactics for ulcerative pyloroduodenal bleeding. The basis of the algorithm is the active use of endoscopic diagnostics and treatment based on the classification of bleeding from peptic ulcers which is shown in Fig. 1. | Figure 1. An algorithm for the treatment and diagnostic tactics of managing patients with ulcerative pyloroduodenal bleeding |

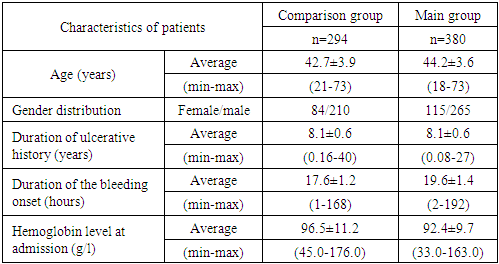

The general characteristics of patients with bleedings are presented in Table 1. The average age of the patients was 44.2 ± 3.6 and 42.7 ± 3.9 years in the main and comparison groups, respectively. The duration of ulcerative history in patients of both groups was approximately equal and averaged 8.1 ± 0.6 years. The duration of the bleeding onset was 19.6 ± 1.4 and 17.6 ± 1.2 hours in the main and comparison groups, respectively. The following hemoglobin levels were determined at the admission of patients to the hospital: 92.4 ± 9.7 g / l in the main group and 96.5 ± 11.2 g / l in the comparison group.Table 1. General characteristics of patients with bleedings

|

| |

|

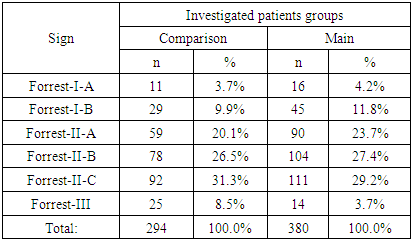

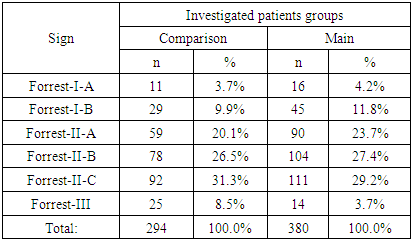

When assessing the degree of ulcerative bleeding according to the Forrest classification (1974) it was found that there were signs of recent bleeding in most cases, while in 59 (20.1%) and 90 (23.7%) patients in the comparison group and the main group visible necrotic vessel was revealed (Forrest-II-A); in 78 (26.5%) and in 104 (27.4%) cases – endoscopic picture with a fixed blood clot (Forrest-II-B); Forrest-II-C activity detected in 92 (31.3%) patients of comparison group and in 111 (29.2%) cases of the main group. Signs of active bleeding according to Forrest-I-A were identified in 11 (3.7%) cases of the comparison group and in 16 (4.2%) of the main group, Forrest-I-B in 29 (9.9%) and 45 (11.8 %) cases, respectively. The ulcer with a clean (white) bottom according to Forrest-III was detected with the lowest frequency - in 25 (8.5%) patients of the comparison group and in 14 (3.7%) of the main group (Tab. 2).Table 2. Bleeding activity by the Forrest classification (1974)

|

| |

|

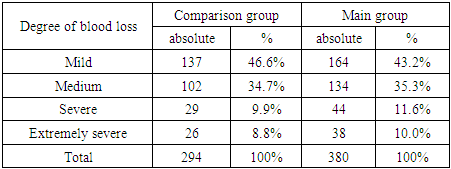

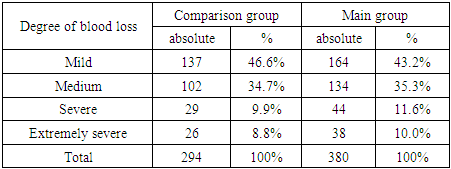

The distribution of patients with ulcerative bleeding according to the severity of blood loss is shown in Table 3. The mild degree was most often determined - 137 (46.6%) and 164 (43.2%) cases in the comparison group and the main group, respectively. The rate of bleeding with an extremely severe degree was 10.0% (38 cases) in the main group and 8.8% (26 observations) in the comparison group.Table 3. Distribution of patients with ulcerative bleeding according to the severity of blood loss

|

| |

|

3. Results

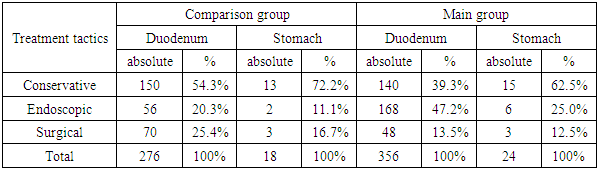

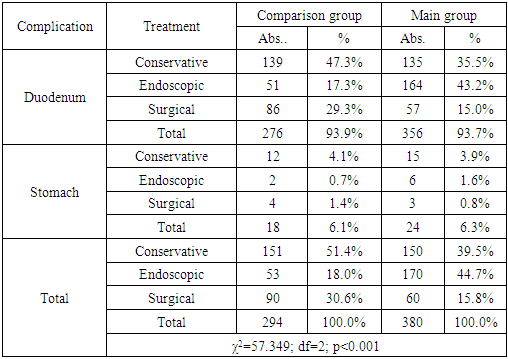

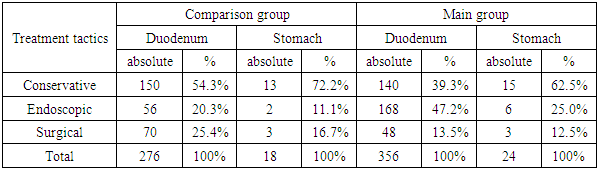

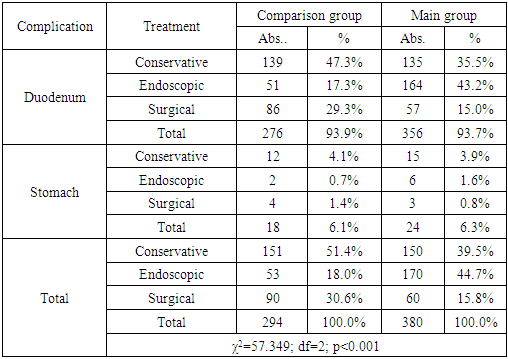

Conservative, endoscopic and surgical treatment methods were undertaken with different frequencies in the analyzed groups. In the main group of patients with duodenal ulcers, surgical activity was only 13.5% (48 of 356 patients), conservative therapy was performed in 140 (39.3%) patients, endoscopic arrest of bleeding in 168 (47.2%) cases (Tab. 4).Table 4. The distribution of patients according to the primary treatment tactics depending on the ulcer location

|

| |

|

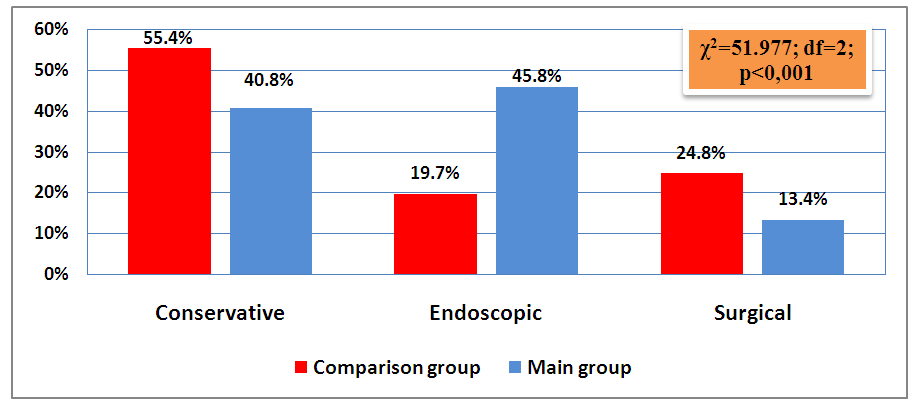

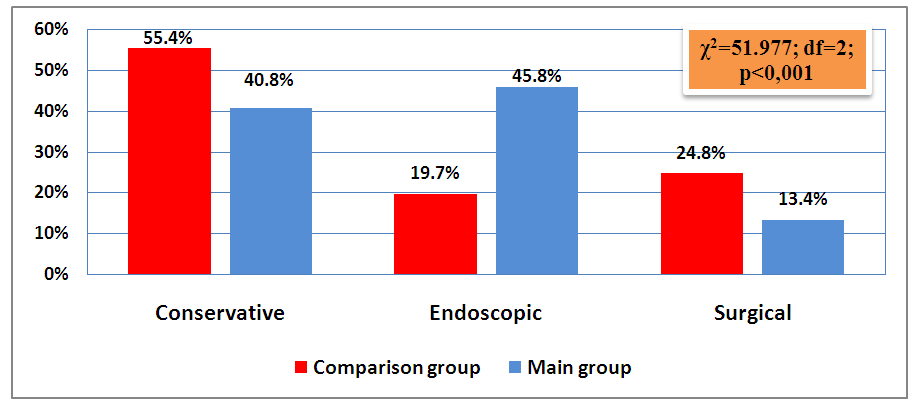

Conservative therapy was undertaken in more than half of cases - 62.5% (15 of 24) and surgical tactics was chosen in only 3 (12.5%) cases in the main group of patients with gastric ulcer. We also observed the active use of conservative therapy of ulcerative bleeding in patients in the comparison group. However, unlike the main group, surgical activity was higher and made up 25.4% (70 of 276) for duodenal ulcers and 16.7% (3 of 18) for gastric ulcers.According to the results of the summary distribution of patients by the undertaken primary treatment tactics (Fig. 2), it can be seen that the proportion of endoscopic interventions was higher in the main group and made up 45.8%, while in the comparison group this indicator was 19.7%. Conservative therapy, as the main method of treatment, was performed in the comparison group in more than half of cases (55.4%), in contrast to the main group (40.8%). The frequency of surgical treatment tactics with a significant difference was higher in the comparison group and made up 24.8% versus 13.4% in the main group of patients (χ2 = 51.977; df = 2; p <0.001). | Figure 2. Summary distribution of patients according to the primary treatment tactics |

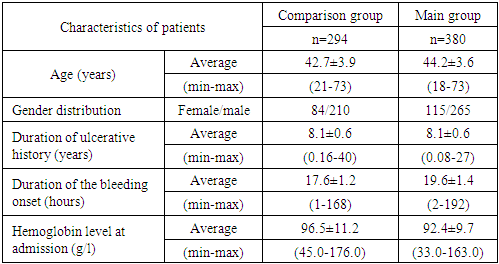

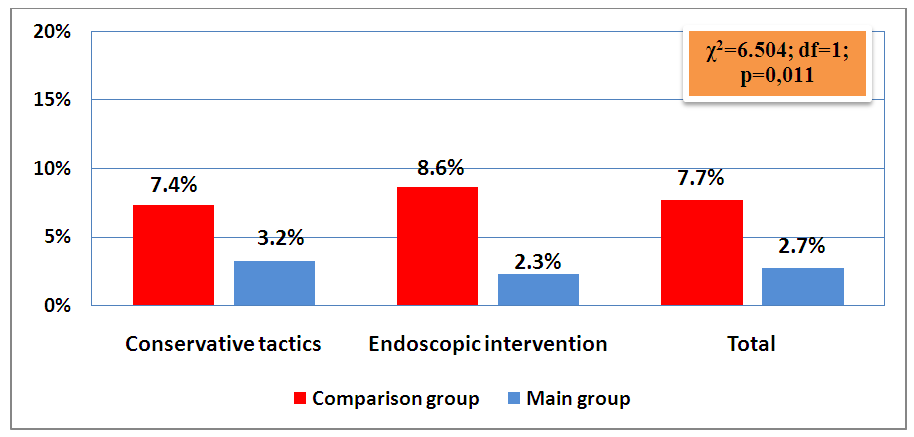

Table 5. The frequency of early relapse of ulcerative bleeding against the background of conservative and endoscopic treatment tactics

|

| |

|

Relapse of bleeding in the comparison group with duodenal ulcer was observed in 7.3% (11 of 150) cases against the background of the undertaken conservative therapy and in 8.9% (5 of 56) cases after endoscopic treatment. The frequency of early relapse of bleeding at gastric ulcer was 7.7% (1 of 13) and 0.0% against the background of the conservative and endoscopic therapies, respectively (Table 5).The main group showed better results. So, there was no relapse of bleeding at gastric ulcers, and at duodenal ulcers the rates of bleeding relapse were as follows: 3.6% (5 of 140) and 2.4% (4 of 168) against the background of conservative and endoscopic treatment tactics, respectively (Table 5).

4. Discussion

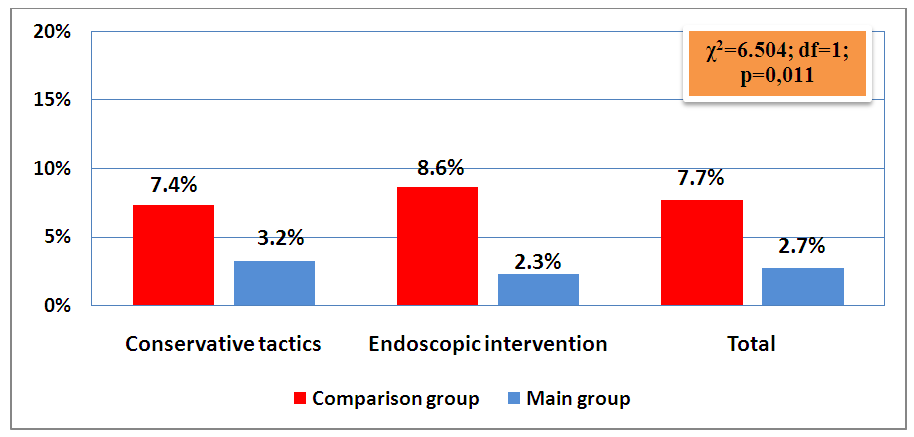

An analysis of the summary data showed that the rate of early bleeding relapse in the main group was lower and made up 3.2% (5 of 155) versus 7.4% (12 of 163) in the comparison group after conservative treatment tactics, 2.3% (4 of 174) versus 8.6% (5 of 58) after endoscopic treatment tactics in the main and comparison groups, respectively (Fig.3).  | Figure 3. The summarized frequency of early relapse of ulcerative bleeding on the background of conservative and endoscopic treatment tactics |

Table 6. Distribution of patients by type of final treatment for peptic ulcer complicated by bleeding

|

| |

|

The distribution of patients by the type of final treatment for peptic ulcer complicated by bleeding is shown in Table 6. So, at duodenal ulcers surgical activity was higher in the comparison group and made up 29.3% (86 of 276), while in the main group this indicator was 15.0% (57 of 356) (χ2 = 57.349; df = 2; p <0.001).Endoscopic treatment as the final tactic was comparatively more often used in the main group with a frequency of 43.2% versus 17.3% in the comparison group (χ2 = 57.349; df = 2; p <0.001). At gastric ulcers surgical activity was also higher in the comparison group and made up 1.4% (4 of 18), while in the main group this indicator was 0.8% (3 of 24). Endoscopic treatment was performed in 0.7% (2 of 18) cases in the comparison group, which was significantly lower than in the main group (1.6%).

5. Conclusions

Thus, the improvement of tactical approaches to the treatment of gastric and duodenal ulcers complicated by bleeding with the expansion of indications for the prophylactic performance of hemostatic endoscopic interventions reduced the likelihood of developing an early recurrence of hemorrhage in the group of non-operated patients from 7.7% (relapse was noted in 17 of 221 cases ) to 2.7% (in 9 of 329 patients) (χ2 = 6.504; df = 1; p = 0.011) and in general significantly reduced the need for surgical treatment from 30.6% (in 90 of 294 patients) to 15.8 % (in 60 of 380 patients) (χ2 = 21, 049; df = 2; p <0.001).

References

| [1] | Bagnenko S.F., Sinenchenko G.I., Verbitsky V.G. The use of protocols for the organization of therapeutic and diagnostic care for ulcerative bleeding in clinical practice // Bulletin of surgical gastroenterology. 2006.- No1.P. 57. |

| [2] | Verbitsky V.G., Bagnenko S.F., Kurygin A.A. Gastrointestinal bleeding of ulcerative etiology: pathogenesis, diagnostics, treatment. A guide for doctors. SPb .: - 2004. – P.242. |

| [3] | Zherlov G.K. The choice of radical surgery in patients with sutured perforated gastroduodenal ulcers / G.K. Zherlov, A.P. Wallet, P.C. Rudaya // Surgery. - 2005. - No. 3. – P.16-20. |

| [4] | .Chiu P.W. Surgical salvage of bleeding peptic ulcers after failed therapeutic endoscopy / P.W. Chiu, E.K. Ng, S.K. Wong // Dig. Surg. - 2009. – No 26. -P.243-248. |

| [5] | Nazirov F.G. Prevention of early complications of gastrectomy in connection with peptic ulcer of the duodenum // Therapeutic Bulletin of Uzbekistan. -2015. -No3. - P.339-344. |

| [6] | Sedov V.M. Surgical diseases: a training manual // St. Petersburg M.: Medicine, 2008, Volume I.- P.271. |

| [7] | Khadjibaev A.M., Melnik I.V., Azimov A.A. Improved actively individualized tactics in the treatment of acute gastroduodenal bleeding // Thes. of abstract Russian scientific-practical conf. Sochi, 2006 .-- P. 62. |

| [8] | Khadjibaev A.M., Malikov Yu.R., Halmetov P.M., Melnik I.V., Allayarov U.D. The role of endoscopy in the diagnosis and treatment of gastroduodenal bleeding // Surgery 2005- No. 6 - P. 37–41. |

| [9] | Gisbert J.P., Legido J., Castel I., Trapero M.; Cantero J., Mate J., Pajares J.M. Risk assessment and outpatient management in bleeding peptic ulcer //J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2006. - №2. - P. 129-134. |

| [10] | Hooi JKY, Lai WY, Ng WK, et al. Global Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori Infection: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterology 2017; 153:420. |

| [11] | Riwanindra L., Anubhav V. Controlled tube duodenostomy in the management of giant duodenal ulcer perforation - a new technique for a surgically challenging condition. The American Journal of Surgery. 2009.198; 319-323. |

| [12] | Troland D, Stanley A. Endotherapy of Peptic Ulcer Bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2018; 28(3): 277-289. |

| [13] | Nishanov F.N., Abdullajonov B.R. et al. Surgical tactics for duodenal bleeding of ulcerative genesis // Bulletin of the National Medical and Surgical Center named after N.I. Pirogov -2015.-No3.-P.86-90. |

| [14] | Ertekin C., Yanar H., Taviloglu K., Guloglu R. Can endoscopic injection of epinephrine prevent surgery in gastroduodenal ulcer bleeding? An analysis of 107 cases //Laparoendosc. Adv. Surg. Tech. Am. 2004. - V. 14. №3. - P. 147-152. |

| [15] | Gurusamy KS, Pallari E. Medical versus surgical treatment for refractory or recurrent peptic ulcer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Mar 29; 3: CD011523. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML