-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2019; 9(9): 351-355

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20190909.09

Primary Orbital Rhabdomyosarcoma in a Child

Sagili Chandrasekhara Reddy1, 2

1Department of Ophthalmology, School of Medicine, University Sains Malaysia, Kubang Kerian, Kelantan, Malaysia

2Department of Ophthalmology, Faculty of Medicine and Defence Health, National Defence University of Malaysia, Sungai Besi Campus, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Correspondence to: Sagili Chandrasekhara Reddy, Department of Ophthalmology, School of Medicine, University Sains Malaysia, Kubang Kerian, Kelantan, Malaysia.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

A 3-year-old boy presented with gradually increasing painless protrusion of right eye of two weeks duration. He had right axial proptosis with slightly upward looking eyeball and a soft mass was felt in the lower part of orbit. Anterior segment was normal and fundus showed mild oedema of the optic disc in the right eye. CT scan of the right orbit showed a round mass around the optic nerve. Fine needle aspiration biopsy revealed histological features of embryonal rhabdomyosarcoma. The child was treated with chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Proptosis increased during the hospital stay and the child lost vision in the right eye due to compression of the optic nerve. The child developed radiation keratitis and symblepheron in the upper bulbar conjunctiva. After completion of radiotherapy and three cycles of chemotherapy, the eyeball was enucleated and the remaining tumor mass was removed. At the last follow up (12 months after chemotherapy), there was no recurrence of tumor in the right orbit. However, hypoplasia of the orbit was noted.

Keywords: Rhabdomyosarcoma, Embryonal, Orbital, Proptosis, Chemotherapy, Radiotherapy

Cite this paper: Sagili Chandrasekhara Reddy, Primary Orbital Rhabdomyosarcoma in a Child, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 9 No. 9, 2019, pp. 351-355. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20190909.09.

1. Introduction

- Rhabdomyosarcoma (RMS) is the most common primary malignancy occurring in the orbit in children. It is a malignant neoplasm that is composed of cells with histopathologic features of striated muscle in various stages of embryogenesis. Most ocular RMS arises in the soft tissues of the orbit but they can rarely occur in the other ocular adnexal structures and even within the eye. Primary orbital RMS occurs mainly in children below the age of 16 years in about 90%, with a mean age of 5-7 years [1]. Primary site of ophthalmic RMS was reported in the orbit (76%), eyelid (3%), conjunctiva (12%) and uveal tract (9%) in USA [2]. Orbital RMS in children has been reported to be varying from 4.35% (29 out of 666 orbital malignancies below 10 years age) in Pakistan [3] to 23.4% (18 out of 77 cases of RMS in children below 15 years) in Iran [4]. It is however a comparatively rare lesion for a general ophthalmologist. It should be suspected whenever one sees a rapidly growing unilateral proptosis in a child. The literature review of recent years showed not many case reports from different countries in the world [5-11]. No case has been reported from Malaysia; and therefore, the first and rare case of rhabdomyosarcoma of orbit in a young child is reported.

2. Case Report

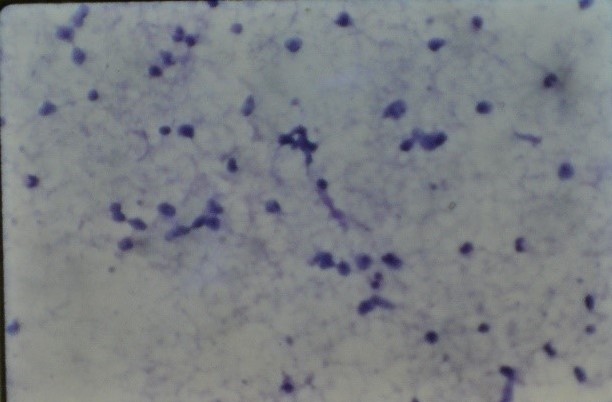

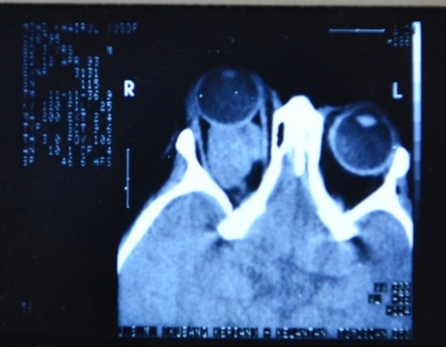

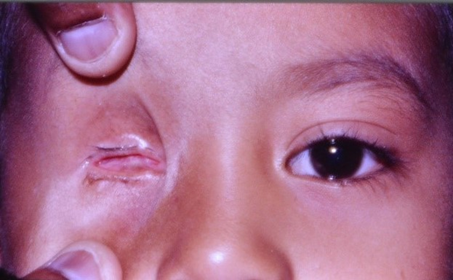

- A 3-year-old boy was brought to the eye clinic by his mother with a complaint of bulging of right eyeball for the past two weeks, which was gradually increasing in size. There was no history of trauma, pain, redness, or deterioration of vision in the eye, but slight watering of eye was present. There was no history of fever, headache, vomiting, epistaxis or nose block. The child was born full term, spontaneous vaginal delivery. Antenatal and postnatal period was uneventful. Developmental milestones were normal. General physical examination was normal. Eye examination: Right eye showed axial proptosis with slightly upward looking eyeball. Vision was poor (counting fingers 3M) and there was chemosis of lower bulbar conjunctiva. A soft mass was felt in the lower part of orbit. (Fig.1); orbital margins were normal. Ocular movements were limited in all directions. Dilated pupil fundus examination showed blurred disc margins with hyperemia of the disc (oedema of the optic disc); blood vessels and macula were normal. Tonopen intraocular pressure was 16 mm Hg. Left eye – anterior segment, ocular movements, intraocular pressure and fundus were normal. Ciprofloxacin eye ointment was started two times in the right eye.Systemic examination did not reveal any abnormality. The differential diagnosis of glioma of optic nerve, rhabdomyosarcoma neuroblstoma, leukemic infiltration and lymphoma were kept in mind and the child was admitted for investigations. All the blood counts were within normal limits; the blood smear did not show any blast cells. Renal function tests and liver function tests were normal. Urine examination for vanillylmandelic acid (VMA) spot test was negative. Ultrasonography of abdomen was normal. X-ray chest and X-ray orbits were normal.

| Figure 1. Right eye showing a soft mass in the lower part of the orbit and chemosis of lower bulbar conjunctiva |

| Figure 2. CT scan of orbits and brain showing moderate size extraconal mass behind the right eyeball causing proptosis |

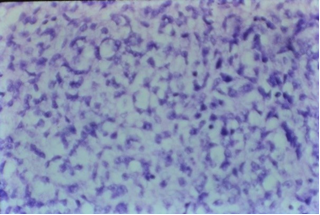

| Figure 3. Fine needle aspiration biopsy material showing small to large size cells with dark hyperchromatic nuclei, and occasional mitotic figures (H and E, x 40) |

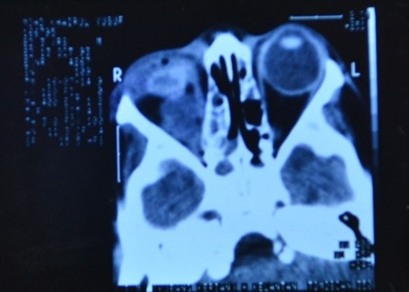

| Figure 5. CT scan of orbits showing reduction in the size of the tumor mass in the right orbit |

| Figure 6. Right eye showing hypoplasia of right orbit, empty socket without any recurrence of tumor (12 months after completion of treatment) |

3. Discussion

- The most characteristic presentation of primary orbital RMS is the rapid onset of unilateral proptosis and infeirotemporal displacement of the globe. Proptosis can develop rapidly within a few days, or less commonly, present as a gradual painless process. Further, patients may present with a history of worsening eyelid edema and erythema, chemosis, ophthalmoplegia, blepheroptosis, or a palpable mass. Ocular or orbital pain is less common presenting symptoms. A history of trauma is sometimes associated with the presentation of tumour. Posterior located tumours are more commonly associated with choroidal folds, retinal detachment, retinal vessel tortuosity and optic disc edema with optic neuropathy. Large tumours are more likely to cause extraocular motility restriction, severe proptosis and optic nerve compression [13]. In the present case, the child presented with proptosis and a soft mass in the lower part of orbit. However, the CT scan showed a moderate size mass behind the globe, confining to the extraconal space and causing right eye proptosis; the mass was not extending into the brain (Fig.2). Metastatic spread of orbital RMS is uncommon; if left untreated RMS can potentially metastasize to the lung, bone and bone marrow via haematogenous spread. The clinical diagnosis of orbital RMS is based on a detailed history, ocular examination, investigations to rule out other causes of proptosis in a child, imaging studies including CT/MRI. Other diseases causing proptosis such as orbital cellulitis, lumphamgioma, dermoid cyst, haemangioma, metastatic neuroblastoma and lymphoma are to be excluded by detailed history and relevant investigations. Biopsy confirms the final diagnosis of RMS after histopathology and immunochemical studies. Electron microscopy may be helpful, if histopathological diagnosis is uncertain, by demonstrating parallel arrays of thick myosin filaments [1].In the present case, after doing all the investigations other causes such as orbital cellulitis, leukaemic infiltration, lymphoma, neuroblstoma, glioma of optic nerve, dermoid cyst were excluded and the diagnosis was confirmed after fine needle aspiration biopsy and immunohistochemistry stain for myosin. Even though the cross striations were not seen typically, the diagnosis of embryonal RMS was made on the presence of tad pole appearance of cells and presence of myosin on immunohistochemistry stain. Previously RMS was believed to arise from extraocular muscle, but now it is thought that it originates from pluripotent mesenchymal cells that have the ability to differentiate into skeletal muscle [1,14]. In a comprehensive report of 264 patients from the Intergroup Rhabdomyo- sarcoma Study, the tumor type was classified as embryonal in 84%, alveolar in 9%, and boyroid in 4% of cases. Pleomorphic RMS is very rare in the orbit and generally occurs in adults [15]. Kaliaperumal et al [6] reported embryonal type in 4 out of 6 orbital RMS cases in children aged between 4 and 10 years.Embryonal RMS is the most common histological type seen in the orbit and generally has a favorable prognosis. It is composed of alternating cellular and myxoid areas. The tumor cells are arranged with a centrally located hyperchromatic nucleus surrounded by considerable amount of eosinophilic cytoplasm. The rhabdomyoblastic cells may show cross striations in 30%, representing cytoplasmic bundles of actin and myosin filaments. Alveolar RMS is the least common variety and carries the worst prognosis. It consists of eosinophilic rhabdomyoblasts that are loosely adherent within thin hyalinized septa. The tumor cells at the periphery of alveoli are often well preserved while those free floating at the centre are loosely arranged and poorly preserved. Only 10% show striations. Botyroid RMS are considered a variety of embryonal type, most often appears as a fleshy grape-like or papillomatous mass in the forniceal conjunctiva. Histologically it appears similar to embryonal type. Immunohistochemical stains for desmin, myosin, muscle specific actin and myoglobin have become the main histopathologic approach to establish the diagnosis of RMS and differentiating from other spindle cell tumors [16].Orbital exenteration was performed in 2 out of 28 patients with extraocular RMS [2]. Survival rates when utilizing surgery alone (primary exenteration) were as low as 30% for primary orbital RMS [17]. With the introduction of surgery (excision + orbital extenteration) combined with adjuvant chemotherapy (vincristine + actinomycin D + cyclophosphamide) and radiotherapy (4000 – 5400 cGy over 4-5 weeks) the life prognosis is favorable [2]. Favorable prognosis may be related directly to tumor site, earlier detection with smaller tumor, histological cell type. Embryonal type of RMS has better prognosis than alveolar type [2,4]. Survival rate in pediatric RMS has been reported to be 5 years in 90% of cases [2]; and 10 years in 94% [4], and 100% [18] of these patients. The chemotherapeutic agents and radiation treatment are known to have complications. Cyclophosphamide is commonly associated with keratocomjunctivitis sicca and blepheroconjunctivitis, and less commonly lacrimal duct stenosis and cataract [19]. Ocular morbidity secondary to the local effects of radiation on the orbital soft tissue and globe include punctate epithelial keratitis, conjunctival injection, orbitofacial bony hypoplasia, enophthalmos secondary to orbital fat atrophy. Vision threatening complications such as dense corneal scarring, cataract, radiation retinopathy, macular scarring, and phthisis bulbi [20]. The reported late effects of treatment included cataract in 55%, dry eye in 36%, orbital hypoplasia in 24%, blepheroptosis in 9%, and radiation retinopathy in 9% out of 28 cases [2]. In the present case, primary surgical treatment was not done. The child was treated with chemotherapy and radiotherapy. The child had complications such as exposure keratitis secondary to severe proptosis; conjunctival edema, punctate epithelial keratitis, corneal scarring secondary to radiation treatment; loss of vision due to compression of optic nerve by the tumor in the orbit. However, the size of the tumor reduced after radiation treatment. After completion of chemotherapy, excision of the residual tumor was done. Orbital hypoplasia was noted on the right side during follow up. He was followed up for 1 year without any recurrence of the tumor in the right orbit; later on he defaulted follow up.Orbital hypoplasia is a known late complication following radiation treatment in children, and it was reported in 24% by Shields et al [2] and in 42% by Eade et al [18] of the orbital rhabdomyosarcoma cases.Even though the patient is seen and diagnosed as a case of orbital RMS by the ophthalmologist first, the surgery is possible in patients with small tumors only. The orbital exenteration procedure for large size tumors is performed usually in places where the chemotherapy and radiotherapy facilities are not available [9]. Currently, in patients with large tumors, the chemotherapy or radiotherapy or combined treatment is given to reduce the tumor size and kill the cancer cells. Later on the residual tumor is removed surgically.

4. Conclusions

- Most ocular rhabdomyosarcomas arise in the soft tissues of the orbit but they can rarely occur in the other ocular adnexal structures and even within the eye. Orbital RMS poses significant challenge for the ophthalmologist in terms of its diagnosis and management. Its clinical diagnosis is based on a detailed history, ocular examination, investigations to rule out other causes of proptosis in a child, imaging studies including CT/MRI. Survival of orbital RMS has improved due to advances in chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Post treatment complications, including side effects of radiotherapy as well as visual dysfunction, occur more often and present new challenges due to improved long-term survival. There is a need of good cooperation between ophthalmologist, pediatric oncologist, radiation oncologist, and rehabilitation specialists for successful management and survival of these patients.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML