-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2019; 9(8): 293-297

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20190908.04

Prevalence of Acromegaly in the Republic of Uzbekistan

Zamira Y. Khalimova, Adliya O. Kholikova, Umida A. Mirsaidova, Dildora H. Abidova

Department of Neuroendocrinology with Pituitary Neurosurgery, Center for the Scientific and Clinical Study of Endocrinology, Tashkent, Uzbekistan

Correspondence to: Adliya O. Kholikova, Department of Neuroendocrinology with Pituitary Neurosurgery, Center for the Scientific and Clinical Study of Endocrinology, Tashkent, Uzbekistan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

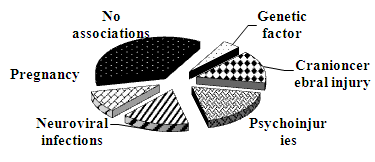

Acromegaly is a rare disease requiring extensive examination of population to get reliable epidemiological data which are of high value for adverse outcomes of the disease to be reduced, as well as for improvement of early diagnosis and results of treatment. The assessment of acromegaly prevalence in the Republic of Uzbekistan as per the National Registry has been performed. The data on 442 patients with the pituitary somatotrophic adenomas entered the Registry database from January 1, 2007 to January 2018. All patients were examined at the local level for the Registry Card to be filled in. The patients’ age varied from 18 to 75 years, mean age was 41 ± 21 years. The findings from the study demonstrated that acromegaly prevalence in the Republic of Uzbekistan is 1.4 cases per 100 000 of population with uneven distribution in the regions of the Republic. High prevalence of the pituitary somatotrophic adenomas was registered in Tashkent-city (2.5) and Namangan region (2.2) with the predominance among women. Late diagnosis of the disease delayed by 6-10 years with the peak at 40-49 years of age for men and at 50-59 years of age for women. Analysis of provoking factors demonstrated that manifestation of the disease was preceded by neuroviral infection (14.6%), psychological traumas and stresses (18.6%), pregnancy (10.1%) and craniocerebral injuries (15.4%). First health-seeking was found delayed corresponding to the height of the disease to be evidenced by the analysis of clinical signs of the disease’s manifestation. The vast majority of the patients were found to seek for help with specialists of other profiles, such as, neuropathologists, therapists and cardiologists; while 43.2% of patients visited endocrinologists, and this is thought to cause high prevalence of the disease and its early complications.

Keywords: Acromegaly, Epidemiology, Risk factors, Clinical features

Cite this paper: Zamira Y. Khalimova, Adliya O. Kholikova, Umida A. Mirsaidova, Dildora H. Abidova, Prevalence of Acromegaly in the Republic of Uzbekistan, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 9 No. 8, 2019, pp. 293-297. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20190908.04.

1. Introduction

- Acromegaly is a rare disease characterized with growth hormone (GH) excess and increased insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) mostly associated with a pituitary adenoma. The disease results in early invalidization and higher mortality among the acromegalics which is 2-4 times higher than the one in the general population [1,2]. 60% and 25% of patients die due to cardiovascular and respiratory disorders, 15% because of malignancies [1,3,4,5]. GH levels < 5mU/l (< 2.5 μg/l) facilitate rapid improvement of acromegaly [4,6]. Maintaining GH and/or IGF-1 normal for the age was found to associate with the reduction in mortality rates regardless of concurrent complications [1,7,8].In 1980-2001 acromegaly incidence was reported to range from 3.8 to 6.9 cases per 100 000 of population; the prevalence was from 0.28 to 0.4 cases per 100 000 of population [9-14]. Recently, in a number of reports from various geographical regions with various levels of public health care systems information on acromegaly incidence and prevalence (0.2-1.1 and 2.8-13.7 cases per 100 000 of population/year, respectively) was provided [15,16]. The epidemiological worldwide data vary. Thus, according to Daly et al., acromegaly prevalence in Belgium is 12.5 cases per 100 000 of population [17]; Tjörnstrand et al. report on 3.3 cases per 100 000 population in Sweden [18]. There are 3.4 cases per 100 000 population in Spain [19], 13.7 in Iceland [20], 12.4 in Malta [21], 7.8 in the USA [9] and 2.8 in the South Korea [10].In epidemiology of acromegaly, it is necessary to elucidate possible geographic variance and effects of environmental factors, ethnicity, sex, level of public health care system and accessibility of medical service, as well as to get information on early onset of the disease, familial susceptibility and mixed GH-PRL secreting adenomas [22].Delay in the diagnosis is still considerable; presence of the disease is usually confirmed in the 5th decade affecting condition of persons of working age, in its turn to result in the decreased working capacity, social and financial consequences, as well as in prolonged burden for the public health care system confirming necessity of higher awareness of medical professionals [23,24].Acromegaly is a rare disease requiring extensive studies aiming at acquiring valid and reliable epidemiological data extremely necessary for reduction of adverse outcomes of the disease, improvement of early diagnosis and patient outcomes, for description of the disease patterns and hypotheses relevant to cause factors, for evaluation of the role the disease plays in the lives of patients, their families and society, as well as for assessment of acromegaly burden for the public health care system [25].For ascertainment of early acromegaly forms and formulation of a strategy for management of the patients with somatotrophic pituitary adenomas the acromegaly registries making it possible to keep tracking of cases, to assess the factors determining manifestation, course and outcomes of the disease, are of great significance. Our work was initiated to analyze data of the National Uzbekistan Acromegaly Registry, which gives the opportunity to impartially assess a situation with diagnosis and efficiency of therapeutic interventions, and to develop the scientifically grounded strategy for prevention of complications and lethal outcomes, and for improvement of the acromegalics’ late-term quality of life.

2. Materials and Methods

- 442 patients with the somatotrophic pituitary adenomas whose data were entered into Uzbekistan Acromegaly Registry database from January 1, 2007 to January 1, 2018, were the object of the study. All the patients were examined at the local level for the personal registry card to be filled up. The patients’ age varied from 18 to 75 years, mean age was 41±21 years.All patients underwent- the clinical examination,- RIA of hormones, such as LH, FSH, TSH, GH, IGF-1, IGFBP-3, cortisol, testosterone, estradiol, free T4, prolactin/- X-ray study including the sella spot filming, CT and/or MRI of the hypothalamo-pituitary region,- US study of inner organs and the thyroid,- Neuro-ophthalmological evaluation of vision acuity, fundus of the eye and fields of vision.To characterize complications we categorized them as cardio-vascular, endocrine-metabolic, respiratory, osteoarticular and neuromuscular, and neoplasms, such as tumors of large intestine, breast, thyroid or prostate) [1,26].

3. Results and Discussion

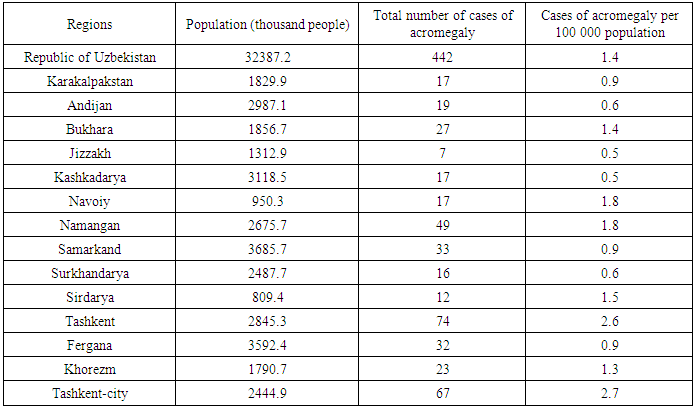

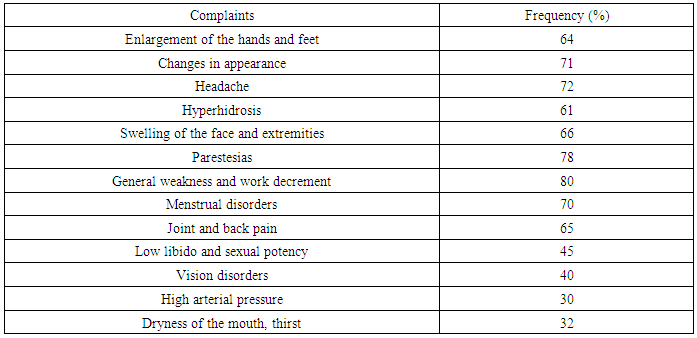

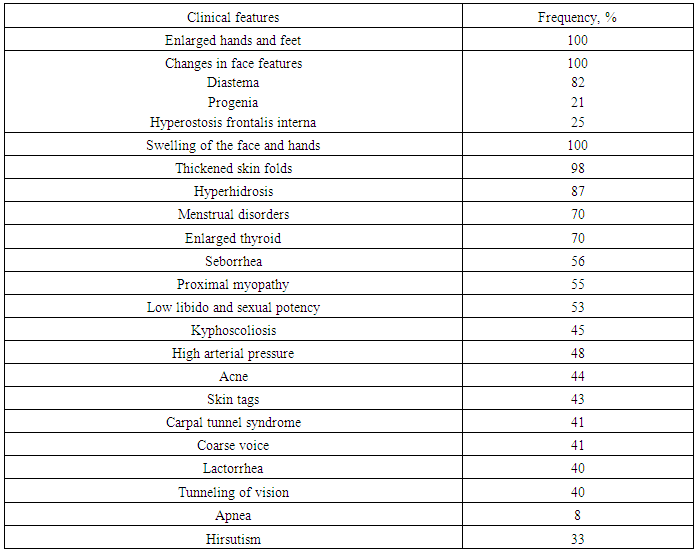

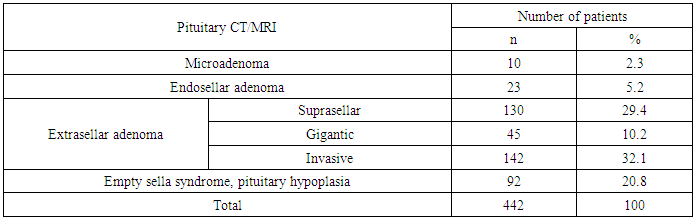

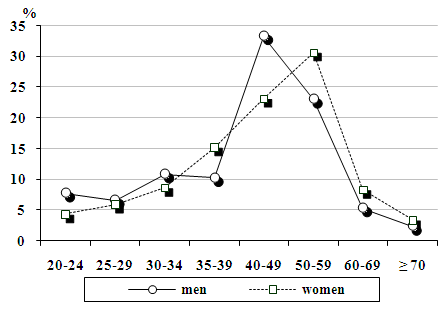

- Of 442 acromegalics, there were 277 (62/6%) women and 165 (37.4%) men. The highest prevalence of the disease was found in patients aged from 30 to 44 years (43.4%), the lowest one could be seen in persons of age group of 75 years and older (2.1%); as a whole the trend persisted for both sexes. Mean prevalence of acromegaly in the Republic of Uzbekistan is 1.4 cases per 100 000 population (Table 1), varying from 0.5 cases in Djizak and Kashkadarya regions to 2.7 per 100 000 population in Tashkent-city. Due to varying acromegaly prevalence, we arbitrarily categorized the regions into those with low, intermediate and high frequency.

|

| Figure 1. Frequency of acromegaly cases by sex and age |

| Figure 2. Risk factors in medical histories of patients in the period prior to acromegaly manifestation |

|

|

|

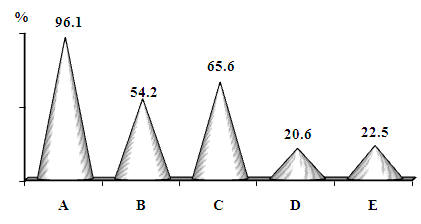

| Figure 3. Complications in the acromegalics. A – endocrine, B – cardiovascular, C – osteoarticular and neuromuscular, D – respiratory, E - neoplasms |

|

4. Conclusions

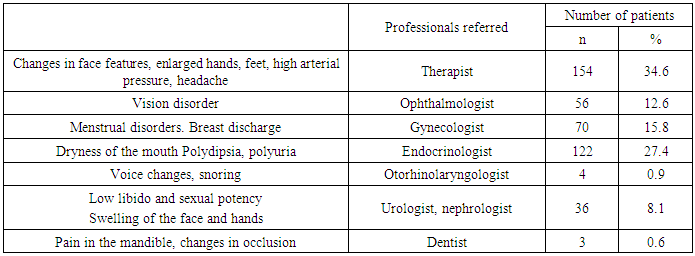

- To sum up, acromegaly prevalence in the Republic of Uzbekistan is 1.4 cases per 100 000 population with non-uniform regional distribution. The highest frequency of the somatotrophic pituitary adenomas was found in Tashkent-city (2.5) and Namangan region (2.2). The female predominance could be clearly seen. The delayed diagnosis by 6-10 years with peaking at 40-49 years among men and at 50-59 years among women was found. As to potential triggering factors, neuroviral infections were found to precede the disease onset in 14.6% of the patients, psychoinjuries and stresses in 18.6%; 101% of women associated the disease onset with pregnancy, 15.4% of patients linked it with the craniocerebral injuries. As the results from analysis of clinical presentation period demonstrated, the patients first sought medical attention late and at the height of the disease. Herewith, most acromegalics sought medical advice of professionals from other than endocrinology area of expertise, that is, of a neuropathologist, a therapist or a cardiologist, while only 27.4% of acromegalics visited an endocrinologist; of all others, this determined high frequency and early onset of complications. The point to be emphasized is that high frequency of complications with affection of endocrine, cardiovascular, and osteoarticular and neuromuscular systems caused by the delayed diagnosis and nonspecific manifestations of the disease which could be confused with arterial hypertension, cephalgia, menstrual disorders and infertility, hypothyroidism and diabetes mellitus.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML