-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2019; 9(7): 242-248

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20190907.04

Prenatal Care Education: An Assessment of Sources and Preferences Regarding Birth Preparedness and Complication Readiness Information among Women in Edo State, Nigeria

Collins Ejakhianghe Maximilian Okoror1, Estelle Sidze2

1Department of Community Health, University of Benin, Benin City, Nigeria

2African Population and Health Research Center, Nairobi, Kenya

Correspondence to: Collins Ejakhianghe Maximilian Okoror, Department of Community Health, University of Benin, Benin City, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

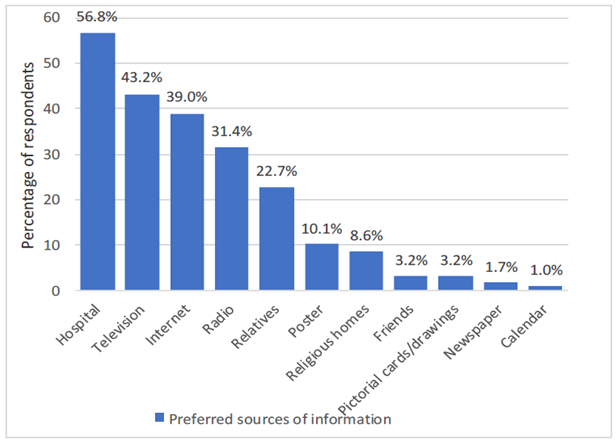

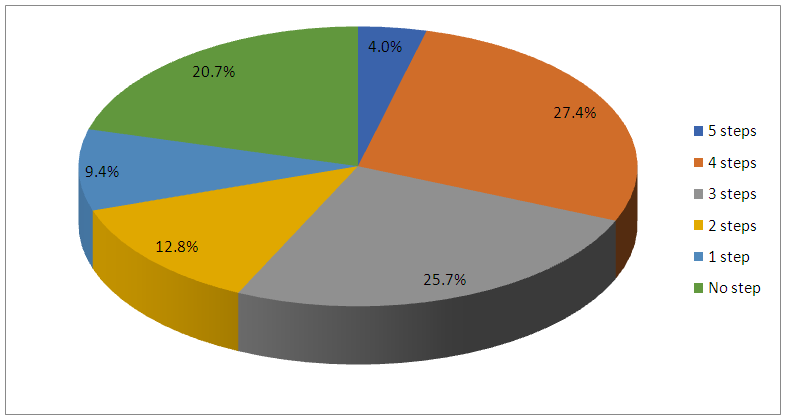

Background: Prenatal care offers the opportunity to advise pregnant women on preparation for birth and its complication and thus improving their preparedness. Unfortunately, prenatal visits are still a missed opportunity to adequately prepare women for birth in African settings. Objective: This study assessed the sources of information on birth preparedness and complication readiness (BAPCR) and the pregnant women preferences in Benin City, Nigeria. Methods: The study was cross-sectional and conducted among 405 pregnant women in their 3rd trimester attending antenatal care in Benin City. A pretested interviewer-administered questionnaire was used. The analysis was both descriptive and multivariate. A p-value of <0.05 was considered as significant. Results: About 74.3% of respondents reported that they received advise on where to go when an emergency arises while only 69 (17%) of them were advised on arranging a blood donor. Fifty-three (13.1%) respondents reported to have been advised on all 5 basic components of BPACR while 15.6% were yet to be advised on any. Hospital (56.8%), television (43.2%) and internet (39%) ranked top of the preferred sources of information. Only 16 (4%) made arrangement for all 5 elements of BPACR while 84 (20.7%) were yet to make any arrangement. Having been advised on at least 3 BPACR elements was associated with women’s preparedness. Conclusion: Information, Education and Communication (IEC) during antenatal care plays a vital role in improving BPACR and hence prevention of maternal death. While hospital is still identified as the appropriate source of information by most of the respondents in this study, there is the need to also utilize other sources of information in order to ensure that more pregnant women are reached with the correct information and also serve as avenues to reinforce the information received during the antenatal clinic sections. There is the need to structure antenatal education and train health educators on BPACR to enhance effective information delivery.

Keywords: Birth preparedness, Complication readiness, Prenatal care education, Sources of information, Preference of information

Cite this paper: Collins Ejakhianghe Maximilian Okoror, Estelle Sidze, Prenatal Care Education: An Assessment of Sources and Preferences Regarding Birth Preparedness and Complication Readiness Information among Women in Edo State, Nigeria, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 9 No. 7, 2019, pp. 242-248. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20190907.04.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- Nigeria is one of the two countries accounting for one-third of the global maternal death, [1] with 814 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births in 2015 [2]. The major causes of maternal mortality in Nigeria include obstetric hemorrhage, infection, hypertensive disorders in pregnancy, obstructed labour and unsafe abortion [3-5]. These causes of maternal mortality can largely be tackled by reducing the three levels of delays –i.e. delays in seeking, reaching and receiving care, and adequate skilled attendance during antenatal and delivery periods.One key approach suggested by the World Health Organization to address the three delays is the inclusion of birth plans in routine prenatal care [6]. Drawing clear birth plans which include a plan for where to give birth, a plan for a birth attendant, a plan for transportation and a plan for saving money is expected to improve pregnant women health seeking behaviors for timely and appropriate care during pregnancy, labor, delivery and the postnatal period [7]. Like a number of sub-Saharan African countries, Nigeria has adopted the WHO’s focused antenatal care (FAC) model which include guidelines for providers to help pregnant women drawing and reviewing birth plans from the first antenatal visit scheduled below 16 weeks of pregnancy [8]. According to the model, the recommended schedule of visits is as follows: the first visit should occur by the end of 16 weeks of pregnancy, the second visit should be between 24 and 28 weeks of pregnancy, the third visit should occur at 32 weeks, and the fourth visit should occur at 36 weeks. However, women with complications, special needs, or conditions beyond the scope of basic care may require additional visits [6].Early detection of obstetric complications results in early treatment and prompt referrals as the case may be. This is of particular importance in Nigeria, a country where there are a lot of barriers militating against ease of accessing health care. Prenatal care is however considered as a missed opportunity since the time required for providing a comprehensive prenatal care consultation, which includes birth preparedness, is insufficient given the current staff shortages and deployment [9, 10]. Studies have showed that BPACR interventions help to reduce delays associated with seeking care for delivery complications [11]. Nikiema et al. [10] in their cross-country analysis on Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) data from 19 countries in sub-Saharan Africa found that health care providers did not routinely give information on pregnancy complications during prenatal care and even when given it was not done in a manner that enable the women to remember. In that study, institutional delivery was found to improve with prenatal care advice on danger signs in pregnancy. BPACR interventions has also been found to improve the utilization of skilled birth attendants [12-14]. In a quasi-experimental study in Kenya employing interventions such as prenatal care education on BPACR, it was observed that there were reductions in delays associated with seeking care and improved rate of delivery by skilled birth attendant [15].Even though birth preparedness and complication readiness is essential for further improvement of maternal and child health, it is still poorly known among women and thus poorly practiced. As reported in the Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS), information received during prenatal care has been reported to be poor in Nigeria as only 67% of women who utilized health facility were given information on obstetric danger signs. Several other regional studies have found that pregnant women are not well prepared for birth and its complications. Idowu et al. [16] in a cross-sectional study conducted among 400 women attending the antenatal clinic at Bowen University Teaching Hospital, Ogbomoso, Nigeria found that only about 40% of women studied were well-prepared for birth and its complications. The knowledge of the respondents on danger signs in pregnancy and labour was poor. In an earlier multicenter descriptive cross-sectional study by Abioye-Kuteyi et al. [17] among pregnant women attending antenatal clinics in Ife Central Local Government Area, Ile-Ife, Osun state only 35% and 66% of the women were birth prepared and complication ready respectively and only about 6% of the women were knowledgeable of obstetric danger signs.Since FAC is centered on the principle that every pregnancy is at risk of complications, it is important that apart from receiving basic care, every pregnant woman should be monitored for complications. Therefore, just like every other routine parts of prenatal care, every pregnant woman should receive information on BPACR, This study assessed the sources of information on birth preparedness and complication readiness (BAPCR) and the pregnant women preferences in Benin City in Edo State, Nigeria. Edo State has the highest figure of prenatal care by skilled provider of the six states in the South-south zone of Nigeria. A considerable number of deliveries still occur outside the health facility. Some of the reasons for this include high costs for delivery, distance to health facility and child born sooner than planned. It is worth noting that of the women who had deliveries outside the health facility in the South-south zone of the country, Edo State had a highest report of child born too early as reason for not delivery in a health facility. This occurrence can be prevented through adequate information on BPACR. Currently, studies are scarce on the sources of information on BPACR and pregnant women’s preferences in the state and this study therefore will fill that evidence gap.

2. Materials and Methods

- This study was a cross-sectional study carried out among 405 pregnant women attending antenatal care clinic in mission hospitals in Benin City, in Edo State. Participants were pregnant women in their 3rd trimester who have attended at least three antenatal clinic follow-up visits and gave consent for the study. Excluded from this study were women who were not capable of giving consent or being interviewed.Data collection was done using a pre-tested structured interviewer-administered questionnaire adapted from the safe motherhood questionnaire of JHPIEGO [18]. The questionnaire contained information on BPACR received during antenatal clinic visits, the various sources that the women considered appropriate for delivering messages on BPACR and the women’s practice of the five basic BPACR elements: i) identified a trained birth attendant; ii) identified a health facility for emergency; iii) identified the mode of transport for delivery and/or for obstetric emergency; iv) saved money and v) identified a blood donor.The data were checked for completeness and consistencies at the end of each day. The analysis was done using statistical IBM SPSS Statistics version 21.0. Descriptive statistics were done to determine the information received by the participants during antenatal clinic visits, sources considered appropriate by the participants in delivery information on BPACR and their preferred sources and the number of steps of the five basic BPACR elements carried out by the participants. Binary logistic regression was computed to determine the predictability of the preparedness of the women by the information they received at the antenatal clinic.A woman was considered as birth prepared and complication ready if she has made arrangement for at least three of the five basic components of BPACR.Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Ethics and Research Committee of the University of Benin Teaching Hospital and institutional approval also sought from the heads of various facilities used. An informed consent was obtained from the study subjects after explaining the study objectives and procedures. Confidentiality and privacy of the respondents were guaranteed during the interview. Respondents were informed that they had the right to decline participation or withdraw from the study anytime and that there would be no penalties or loss of benefits for refusal or withdrawal from the study.

3. Results

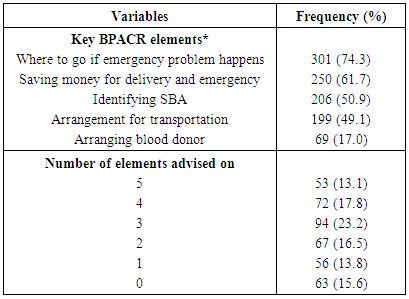

- As shown in table 1, while 301 (74.3%) had advise on where to go if emergency problem happen, only 206 (50.9%) were advised on need to identify a skilled birth attendant. The least advice given was the need to arrange a compatible blood donor. Only 53 (13.1%) had advise on all five basic elements of BPACR while 63 (15.6%) where yet to be advised on any of the elements.

|

|

|

| Figure 1. Preferred sources of information about BPACR as reported by study participants |

| Figure 2. Number of the basic components of BPACR practised by participants |

|

4. Discussion

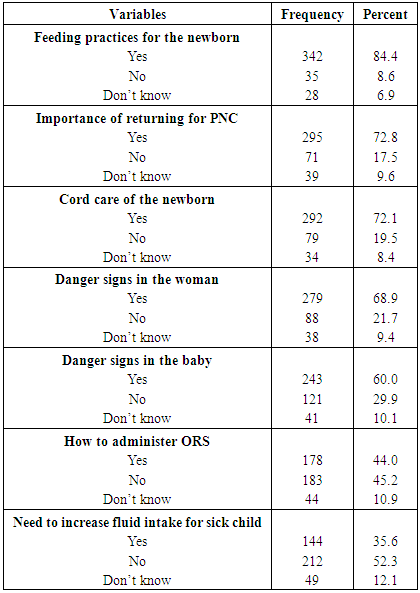

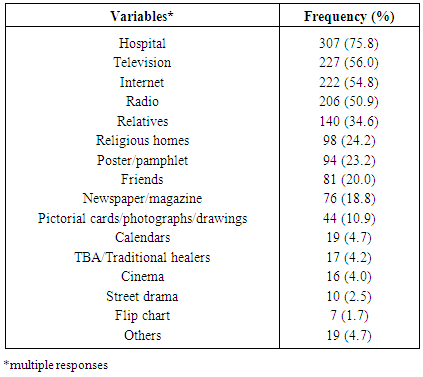

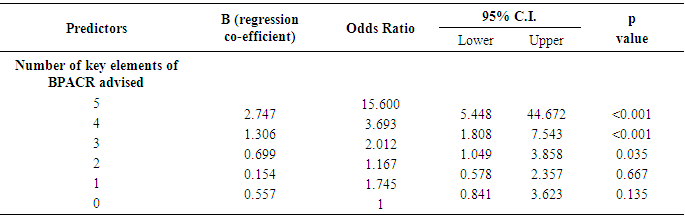

- Antenatal education as an intervention has an impact on the health of the pregnant woman. It provides pregnant women with information that enable them to identify potential obstetric danger signs as well as strategies for birth preparedness and complication readiness [19-21]. As seen in this study, information delivery on key elements of BPACR during the ANC was poor. While most participants reported that they were told of where to go if emergency problem happen and the need to save money for delivery and emergency, only less than half reported being told of need to make arrangement for transportation and an abysmally low 17% of the pregnant women reported been told of need to make arrangement for a compatible blood donor. Not surprising, identifying a compatible blood donor was the least practice by participants in this study similar to that found by Onayade et al [22] among antenatal clinics attendees in Ile-Ife, Nigeria. Yet bleeding accounts for the majority of maternal mortality globally [23, 24]. This could be an indication of the missed opportunities during health talks. So many pregnant women come to the clinics after health talks only to know their progress. This is supported by the fact that only 54.1% of the respondents said they have been advised on at least three of the information about BPACR during the antenatal visit stressing the importance of training for healthcare providers on how to advise pregnant women on components of BPACR. Also, they may be ignorant of the importance of health education sessions thus do not make efforts to attend and participate in the sessions. Another possibility may be that less attention might have been given to the components of BPACR while giving health education and advice during ANC.The study participants reported the hospital as their preferred source of information on BPACR. This is similar to findings by Otaiby et al [25] in their cross-sectional study conducted among pregnant women at primary health centres in Riyadh city, Saudi Arabia where 67.7% of the respondents identified the physician as the most useful source/channel of information. Television and Internet were also identified as preferred sources of information by the participants in this study, unlike in the work by Otaiby et al [25] where mass media and internet ranked low in their list of preferred source of information.Only 4% of the respondents have taken the whole 5 steps of BPACR while about a fifth were yet to commence any of the elements of BAPCR. These findings are in line with other studies in Nigeria, Ethiopia and India where preparation of women in terms of the various components of BPACR was found to be poor [26-28]. Slightly more than half of the pregnant women in this study were found prepared. This figure though low was greater than that found in previous community-based studies [26, 28]. This may be because of the role of antenatal care services in improving the preparedness of pregnant women noted in those studies. Women who attended antenatal care services were found to be better prepared than those that did not attend. In this facility-based study, one expects a higher level of preparedness stressing the importance of training for health providers on how to advise women on components of BPACR.The importance of antenatal information in ensuring the preparedness of pregnant women for birth and complication is again demonstrated by the finding that women who were advised on at least 3 components of BPACR were more likely to be prepared compared to those with no such information. Those who were advised on all 5 components were 15 times more likely be prepared compared to those who had no advice. This further supports previous work where the advice given during ANC was found to be associated with the preparedness of the women [28, 29]. The limitation of this study lies in the fact that there are no universally agreed upon benchmark by which practices of BPACR can be adjudged. Thus, the application of such benchmark on this study was discretionary based on the normative judgment of the researcher. This study was a cross-sectional hence temporal relationship between variables could not be established. The study targeted women who were attending antenatal care clinic at health facilities hence could have missed views of those who never attend ANC clinics. The findings were self-reported with no means of verification of claims made by respondents during questionnaire administration.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

- Information, education and counselling plays a vital role in improving birth preparedness and complication readiness and hence prevention of maternal death. This is usually done during the antenatal clinic sections. This has largely not sufficed in delivery information to pregnant women on BPACR. While hospital is still identified as the appropriate source of information by most of the respondents in this study, there is the need to also utilize other sources of information in order to ensure that more pregnant women are reached with the correct information and also serve as avenues to reinforce the information received during the antenatal clinic sections. During this study, the majority of the respondents identified the hospital, television and internet as preferred sources of information on BPACR. There is no doubt that effective utilization of these sources can go in a long way in improving the knowledge of women on BPACR. This will help to reduce the various delays associated with health care delivery and consequently reduced maternal mortality while improving child survival.The advice given during the ANC was associated with the preparedness of the women. There is, therefore, the need to enact policies that promote antenatal care and develop and disseminate guidelines and protocols for Birth preparedness and complication readiness in all health facilities in Nigeria. Messages on the internet should be regulated to ensure that women get the appropriate message especially in this age of ICT. The federal ministry of health and other regulating agencies should develop and circulate standard operating procedures for antenatal health education sessions in order to ensure that every booked woman receive the information or advice of the day on every of their ANC visits. The television and radio have been identified as appropriate sources of information on BPACR. There should be sessions to talk or discuss issues on BPACR and the need to utilize antenatal care services and skilled birth attendants. This will further help in ensuring that more women get the message and are better prepared.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML