-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2019; 9(3): 90-95

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20190903.05

Knowledge, Attitude and Preventive Measures Regarding Lassa Fever among Residents of University of Abuja Staff Quarters Giri, Gwagwalada Abuja

Egenti NB1, Adelaiye RS1, Sani IM2, Adogu POU3

1Department of Community Medicine, University of Abuja, Nigeria

2Faculty of Clinical Sciences, University of Abuja, Nigeria

3Department of Community Medicine, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Nigeria

Correspondence to: Egenti NB, Department of Community Medicine, University of Abuja, Nigeria.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

Background: Lassa Fever (LF) is an acute viral haemorrhagic fever that has assumed epidemic proportions in many parts of Nigeria. Unfortunately the diagnosis and clinical management of LF pose great challenges because the early symptoms of the disease are often indistinguishable from that of malaria which is endemic in the country. Confirmation of LF requires sophisticated diagnostic technique, often unavailable in most Nigerian health facilities. Prevention is therefore pivotal in the control of LF. This study aims to assess the knowledge, attitude and preventive measures of LF among residents of University of Abuja staff quarters Giri Gwagwalada Abuja. Methodology: A cross sectional study was conducted between March and April 2018 using semi-structured self-administered questionnaires to collect data from consenting 323 respondents selected by systematic sampling technique. Data was analyzed on SPSS version 23 and presented in tables and figures. A p value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Results: Findings revealed that 96% of the respondents were aware of LF, 81.4% had good knowledge. 96% had positive attitude and 89.5% practiced good preventive measures. Of the 323 respondents, 186 (57.6%) said LF was named after an animal. There was poor knowledge of the cause of LF as 45.2% said it was caused by virus, but 93.2% of subjects had knowledge of the vector that transmits it. Ninety-seven percent agreed they would take an approved vaccine to prevent the disease. Age was significantly associated with knowledge of LF while gender was markedly associated with the preventive measure taken. Education was also significantly associated with the knowledge and attitude towards LF. Conclusion: General knowledge, attitude and LF preventive measures were good, but health campaigns and awareness programs are important means of communicating health information and reinforcing existing knowledge.

Keywords: Lassa fever, Knowledge, Preventive measures, Uni-Abuja

Cite this paper: Egenti NB, Adelaiye RS, Sani IM, Adogu POU, Knowledge, Attitude and Preventive Measures Regarding Lassa Fever among Residents of University of Abuja Staff Quarters Giri, Gwagwalada Abuja, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 9 No. 3, 2019, pp. 90-95. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20190903.05.

1. Introduction

- Lassa fever (LF) is a type of viral hemorrhagic fever (VHF) caused by the Lassa virus, a bisegmented ambisense single-stranded RNA virus from the family Arenaviridae. [1] Lassa fever is one of the hemorrhagic fever viruses, occurring in West Africa in similar areas as Ebola virus. There are 100,000-300,000 cases of Lassa fever each year in the world, causing an estimated 5,000 deaths and about 10%-15% of admissions to hospitals in Sierra Leone and Liberia. [2] The multi-mammate rats (Mastomys natalensis) are the natural hosts for the virus, commonly found in rural environment where over 70% of the population resides, they breed frequently and are widely distributed throughout central, west and east Africa. These rats shed the virus in their excreta and humans are infected by contact with the excreta of the rats or by eating them (they are considered as a delicacy in some areas of the endemic region), or food stuff that has been contaminated with the urine of the rodent. The viruses can also be transmitted from person to person which occurs during care of sick relatives or among health care personnel in health care settings. The morbidity and mortality associated with the disease can be reduced by careful management of infected persons, proper and timely control measures and in some cases, administration of prophylactic therapy to relatives and health care workers after exposure. [3]Despite much global effort, advances in research and updated clinical management guidelines, LF continues to be a cause of mortality and morbidity in humans worldwide. Nigeria presently suffers from frequent outbreaks of Lassa fever epidemic, this coupled with paucity of studies and scientific literature on the awareness of LF in Nigeria, this study will hopefully add to the ever growing body of knowledge, provide evidence-based information on the awareness, perception and attitude of Nigerians towards Lassa fever. It will also provide relevant information to stakeholders for community health awareness and campaigns on Lassa fever, and could serve as a baseline for future research. Moreover there is need for close follow up, active case searching, contact tracing and disease awareness (in the community and among health care workers) to remain ongoing. Therefore the objectives of this study include assessing the knowledge of LF among residents of the University of Abuja staff quarters Giri, Gwagwalada Abuja; evaluating their attitude towards the disease; and determining the methods of prevention of LF among them.

2. Methodology

- Study Area: The study was conducted in the university of Abuja staff quarters Giri, Gwagwalada Area Council, along Kaduna – Lokoja road in Nigeria’s Federal Capital Territory, Abuja. Gwagwalada Area Council has a population of 157,770 [4] according to the National Population Census of 2006. Gwagwalada is characterized by two distinct seasons; the rainy and dry seasons. The rainy season starts fully from May to October while the dry season starts from November to April. [5] Temperature ranges from 30 to 37°C yearly with the highest temperature experienced in the month of March. [6] The mean annual rain fall is approximately 1,650 mm. Sixty percent of the rain falls in the months of July and September. [7] This weather condition perhaps favours Mastomys natalensis, a natural host and reservoir of the LF pathogen. [3] The multimammate rat is a commensal rodent ubiquitous in Africa. The culture of hunting and eating the rodents in most parts of Africa also tend to sustain the yearly transmission LF because humans probably get infected by eating contaminated food, by inhaling virus-contaminated aerosols, or while butchering infected rat meat. [3]Study Population: The target population consists of residents of the University of Abuja staff quarters. A sample of the population who gave informed consent was studied. Study Design: The study is quantitative cross-sectional in design and it was carried out between March and April 2018.Sample Size Estimation: The sample size would be calculated using the Leslie-Kish formula. [5]n=Z2pq/d2, Where n is the desired sample size, Z is standard normal deviate taken as 1.96, p is prevalence taken as 70.0% (0.70) for population below 10,000, q= 1-p (0.30) and d is the degree of precision taken as 5% (0.05), n= (1.96)2 x 0.70.0.30/ (0.05)2. n=3.84 x 0.21/0.0025 =0.8064/0.0025, =322. Add 10% (32) for non-response = 354.Inclusion criteria: Individuals above 15 years of age, resident in the University of Abuja staff quarters, and who consented to be part of the study.Sampling Technique: The multi-stage sampling method was used. This involved the selection of Gwagwalada Area Council from 6 clusters of Area Councils using simple random sampling technique. This was followed by selection of Giri ward from the 10 wards of Gwagwalada Area Council, then selection of University Staff Quarters from the 5 communities of Giri Ward. Using the National Population Commission’s house-to-house numbering system, eligible households were selected by simple random sampling technique until the required sample size was completed. Data collection: Data was collected using a semi-structured, self-administered questionnaire made up of six sections; A: socio demographic data, B: the knowledge of lassa fever, C: knowledge of the causes and transmission of Lassa fever, D: knowledge of manifestation of lassa fever, E: attitude towards Lassa fever, and F: knowledge of method of prevention of lassa fever. Research assistants were trained on proper administration and accurate data keeping for two days. The study participants were visited at their homes and questionnaires administered.Data Analysis: Data was analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 23 and presented in charts and in frequency distribution tables. Chi-square test of significance was used to ascertain association between socio-demographic variables and outcomes. P-value set as ≤ 0.05.Ethical Consideration: Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Health Research Ethics Committee (HREC) in the University of Abuja Teaching Hospital (UATH). Informed consent was also obtained from all respondents after adequate explanation of details of the study. Limitations: Some eligible respondents were not present, and some even refused to give consent in the absence of the head of the house hold. However, with repeated visits, consent was given. Also, the researchers, limited by resource constraints, did not collect data from more broad areas order than Abuja University staff quarters. Nonetheless, this research would serve as one of the pilots in readiness for a possible future nationwide study that will more adequately inform the national health policy on control of VHF epidemics.

3. Results

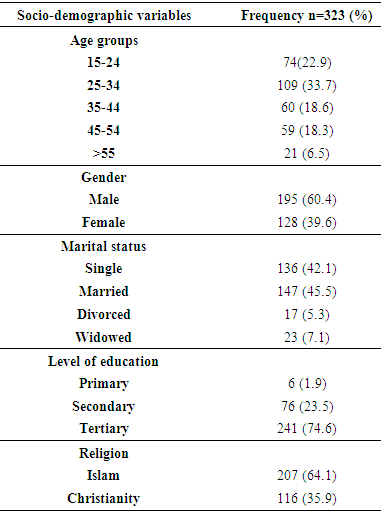

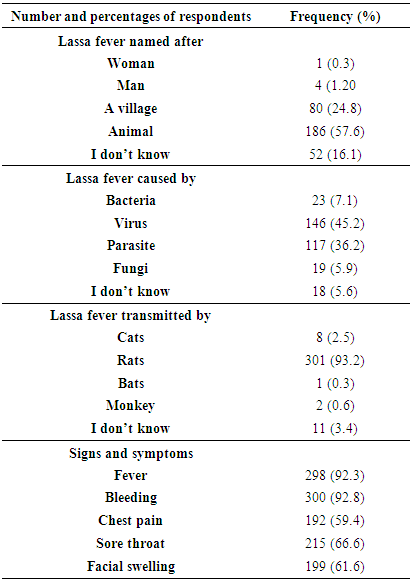

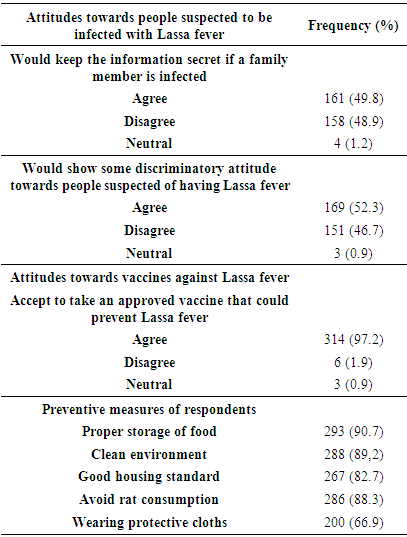

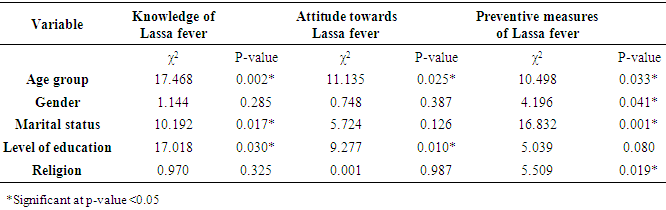

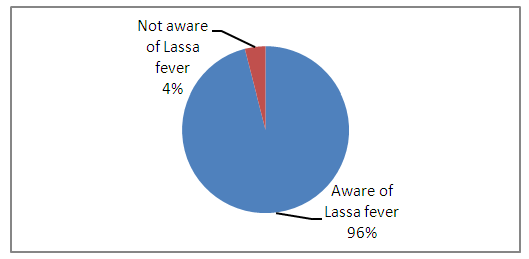

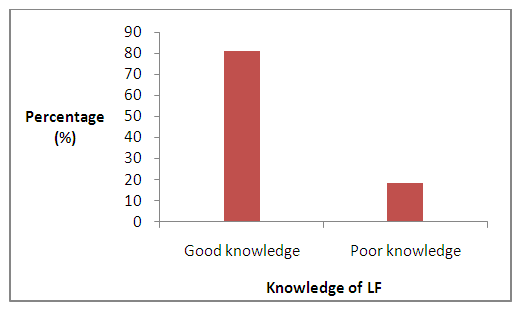

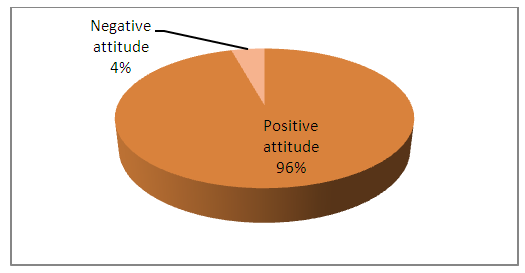

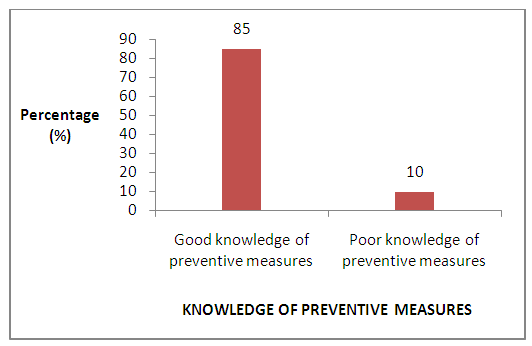

- A total of 350 questionnaires were administered out of which 323 were properly completed and returned giving a response of 92.3%. Table 1 summarizes the socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents. Majority of the respondents (33.7%) were within the age group 25-34. Of the 323 respondents, 195 were males and 128 were females. Seventy five percent of the respondents have attained tertiary level of education. Most of the respondents were Muslims (64.1%), while 45.5% were married. Table 2 shows knowledge of Lassa fever among respondents. About 57.6% said lassa fever was named after an animal, while 45.2% identified a virus as the cause of Lassa fever and rats (93.2%) as the vector that transmits Lassa fever. Among the 323, majority (92.3%) said bleeding and fever were the most common clinical manifestations, while chest pain, sore throat and facial swelling had 59.4%, 66.6%, 61.6% respectively. Figure 1 indicates that out of the 323 respondents, only 4% were not aware of Lassa fever while figure 2 shows majority of the respondents (81.4%) had good knowledge while 18.6% had poor knowledge of LF. Similarly, figure 3 shows that 96% displayed positive attitude towards LF prevention. Table 3 showed that 49% agreed they would keep the information secret if a family member was infected. However, 52.3% agreed that they would show discriminatory attitude towards people suspected of having Lassa fever. About 97.2% were willing to take an approved vaccine that could prevent Lassa fever. Also 90.7% said proper storage of food, followed by clean environment could prevent Lassa fever, while the least (66.9%) agreed on wearing protective cloths. In summary, 85% were knowledgeable about good preventive measures while only 10% showed poor knowledge; (Figure 4). Table 4 summarizes the result of the cross tabulation and pearson’s chi-square test. It shows that the age of respondents significantly predicted the level of knowledge, attitude and preventive measures of Lassa fever, (p<0.05). Gender affected only the preventive measures of Lassa fever at p<0.05. Also marital status was significantly associated with knowledge and preventive measures of Lassa fever. There was also a significant association (p<0.05) between level of education and knowledge and attitude towards Lassa fever. Religion only affects preventive measures of Lassa fever (p<0.05).

|

| Figure 1. Awareness of Lassa fever among the Respondents |

| Figure 2. General knowledge of Lassa fever among the respondents |

| Figure 3. General attitude of respondents towards Lassa fever |

| Figure 4. Knowledge of preventive measures of LF among respondents |

|

|

|

4. Discussion

- Majority of the respondents were in the age group of 25-34 years and attained mainly tertiary level of education. This study was conducted in a university environment where there is high level of education. This is similar to the findings of Reuben et al. [8] Majority of the respondents were married, this is most likely because most of the households were occupied by couples.Awareness is the first step to knowledge, and both are important factors in determining attitude towards and/ or preventive measures of a particular subject. The level of awareness was high 96.0% which is similar to findings in other studies such as Olayinka et al [9] in south west Nigeria; Ighedosa et al [10] south-south Nigeria; also of Adeleye et al. [11] But this finding is different from that in a study done in Kenema, Sierra Leone, where there is less than average level of knowledge. However, it is to be noted that the Kenema study was done in the lay community, while this study was conducted in a university environment which invariably possess better knowledge about health issues. Awareness was evident among those who had tertiary level of education. Unlike the high level of awareness, only about half of the respondents had comprehensive knowledge about Lassa fever. Majority of the respondents mentioned that Lassa fever was named after an animal (57.6%), instead of a village. Only 45.2% knew Lassa fever was caused by a virus, followed by parasite 36.2%. There was good knowledge (93.2%) that Lassa fever was transmitted by rats. Also the respondents had good knowledge of clinical manifestation. This is similar to the finding of Tobin et al [12] and Olayinka et al [9]. Closely related to this is the attitude of the respondents towards people suspected to be infected with Lassa fever, 49.8% of the respondents would keep the information secret if a family member is infected and 52.3% would show some discriminatory attitudes towards such individual. Majority of the respondents would accept to take vaccine against Lassa fever. The association between preventive practices and level of education was significant p<0.05. More respondents with tertiary level of education reported good preventive measures than those who had secondary and primary level of education. Good value system are first and best acquired at home and strengthened by good tutelage in the primary and secondary schools. Generally the level of knowledge, attitude and preventive measures were good, but regular health campaigns and awareness programs are important means of communicating and internalizing health information, reminding and reinforcing existing knowledge.

5. Recommendations

- Despite the good knowledge of Lassa fever elicited from the respondents, sustained efforts at public health education should be carried out by the Federal Ministry of Health, and Federal Capital Territory (FCT) also the Primary Health Care Development Board (PHCDB) considering Nigeria as within the epidemiological zone. These agencies should embark on regular awareness programs, sharing of flyers and posters with appropriate messages on LF and its prevention.Gwagwalada Area Council together with the Ministry of Environment should also provide adequate and efficient environmental sanitation services and amenities which may include employing environmental sanitation staff and officers, making trash cans and dumpsters available, especially in public places and making sure they are appropriately emptied and disposed of regularly.In healthcare settings, thee information education and communication messages should include: staff should always apply standard infection prevention and control precautions when caring for patients, regardless of their presumed diagnosis. These include basic hand hygiene, respiratory hygiene, use of personal protective equipment (to block splashes or other contact with infected materials), safe injection practices and safe burial practices. Health-care workers caring for patients with suspected or confirmed Lassa fever should apply extra infection control measures to prevent contact with the patient’s blood and body fluids and contaminated surfaces or materials such as clothing and bedding. When in close contact with patients suffering from Lassa fever, health-care workers should wear face protection (a face shield or a medical mask and goggles), a clean, non-sterile long-sleeved gown, and gloves (sterile gloves for some procedures).Laboratory workers are also at risk and should not be forgotten. The message should be reinforced that samples taken from humans and animals for investigation of Lassa virus infection should be handled by trained staff. Such samples should be processed in suitably equipped laboratories under maximum biological containment conditions.Prevention of Lassa fever relies on promoting good “community hygiene” to discourage rodents from entering homes. Therefore regular health information should be directed at the community on effective methods of storing grain and other foodstuffs in rodent-proof containers, disposing of garbage far from the home, maintaining clean households and keeping cats. This is because Mastomys are so abundant in endemic areas and it is not possible to completely eliminate them from the environment. Finally, family members should be informed about the need to show utmost care to avoid contact with blood and body fluids while caring for sick persons.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML