-

Paper Information

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2019; 9(1): 14-19

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20190901.03

Knowledge of the Health Risks Associated with the Illegal Sale of Drugs in Pointe-Noire, Congo

Jean Bruno Mokoko 1, Stephane Méo Ikama 1, Benedicte Nganga Kifoula 2, Ange Antoine Abena 3, Gontran Ondzotto 1

1Faculty of Health Sciences, Marine Ngouabi University/ Hospital and University Center of Brazzaville, Congo

2Faculty of Health Sciences, Marine Ngouabi University, Congo

3Pharmacology Laboratory Faculty of Health Sciences, Marine Ngouabi University Congo

Correspondence to: Jean Bruno Mokoko , Faculty of Health Sciences, Marine Ngouabi University/ Hospital and University Center of Brazzaville, Congo.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

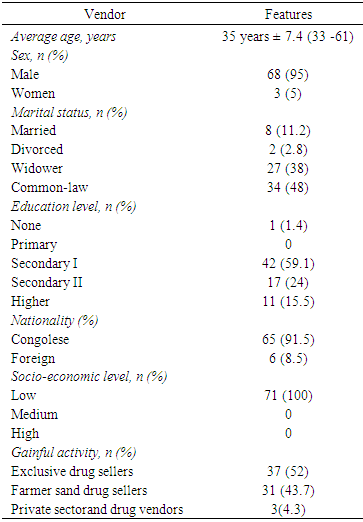

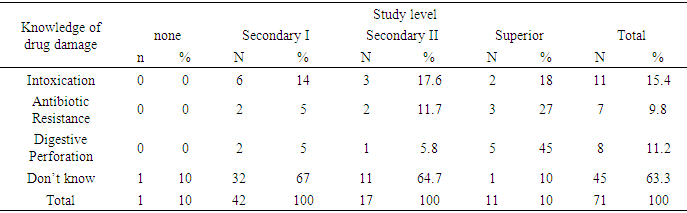

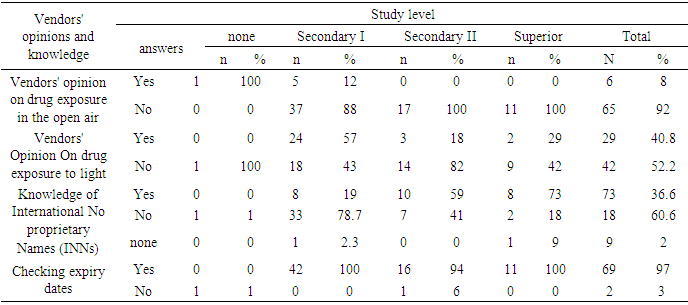

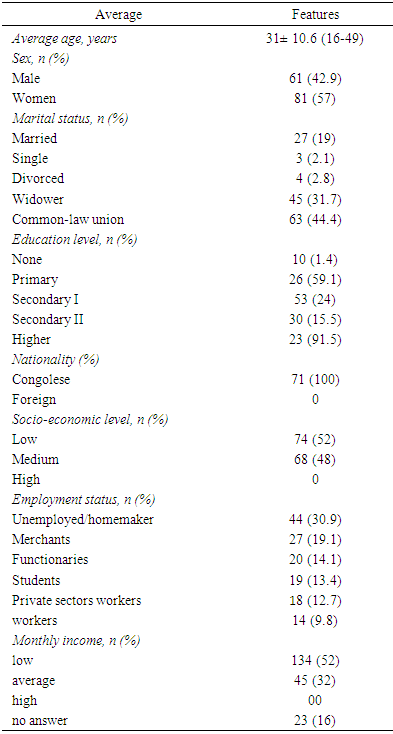

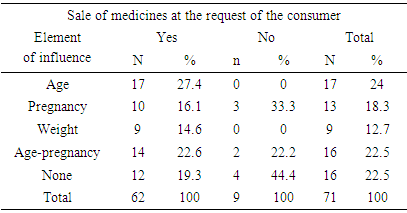

Background: The parallel drug market is booming despite the health consequences. The purpose of our study was to assess the knowledge of sellers and consumers about the health risks associated with the illegal sale of drugs. Material and methods: This was a descriptive cross-sectional study, running from April 1 to August 30, 2014, i.e. 5 months, in the markets of 4 Pointe-Noire districts. Sampling was by simple random selection. Results: The study included 71 sales subjects, aged on average 35±7.4 years, with a secondary level of education in 83.1%. The sources of supply of medicines were local and external. Among the vendors, 51.2% were unaware of the effect of light on drugs, and 63.3% were unaware of the damage caused by these drugs. The study found 142 cases of consumers. The average age was 31±10.6 years. The main reason for purchasing was the low cost (62.7%). The mode of information on the dangers of these drugs was word of mouth in 57% of cases. Conclusion: This trade is an activity of the young subject, the majority of whom is of Congolese nationality.

Keywords: Drugs, Illegal sales, Knowledge, Risks, Congo

Cite this paper: Jean Bruno Mokoko , Stephane Méo Ikama , Benedicte Nganga Kifoula , Ange Antoine Abena , Gontran Ondzotto , Knowledge of the Health Risks Associated with the Illegal Sale of Drugs in Pointe-Noire, Congo, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 9 No. 1, 2019, pp. 14-19. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20190901.03.

1. Introduction

- The phenomenon of illicit drug sales has been steadily increasing worldwide. Its characteristic is the counterfeiting of medicines in developing countries and the sale of medicines on the Internet in European countries. Also, the WHO estimates that the illicit sale of drugs represents 10% of the world market, reaching 25% of the markets of developing countries here 50% of drugs are neither prescribed nor sold according to international standards [1, 2]. To solve this problem, African countries formulated the Bamako Initiative in 1987, which is a policy to strengthen primary health care through the establishment of pharmaceutical policies and a list of essential medicines [2]. However, despite the progress made in recent years on the availability and accessibility of essential generic medicines, nearly a third of the world's population in Asia and Africa still lacks these advances [3, 4]. Indeed, this illegal sale makes available to the population medicines that are often of poor quality, devoid of active ingredients or sometimes poorly dosed with devastating consequences for health. Work in Côte d'Ivoire and Benin reported that more than 72% of the population used these drugs and 86% thought they were of good quality [3, 5]. In Congo, a study conducted in Brazzaville [6] showed that 81.7% of subjects used the parallel market for economic and social reasons. This study was conducted to assess the knowledge of sellers and consumers about the risks associated with the illicit sale of drugs.

2. Materials and Methods

- This was a cross-sectional and descriptive study, running from April 1 to August 30, 2014, for a duration of five (05) months. It was carried out in Pointe-Noire, the economic capital of Congo, in the markets of four (4) districts: Lumumba (large market, border market, in front of Adolphe Sicé General Hospital), Mvoumvou (Mvoumvou market, Mayaka market), Tié-Tié (Tié-Tié market) and Loandjili (Nkouikou market, Muongo-Kamba market, Faubourg market, in front of Loandjili General Hospital). The target population was street drug sellers and consumers. We included in our study: fixed vendors located in markets and/or in front of hospitals as well as street drug consumers present on the day of the survey. However, we did not include in our study: street vendors, vendors and consumers who did not give their informed consent. Sampling was done by a simple random draw of sellers by market because there is no data indicating the exact number of sellers by market and we considered two consumers for every seller buying the drug on the day of the survey. The sample of our study consisted of 71 vendors and 142 consumers. Data were collected after individual interviews using two semi-open questionnaires, one for vendors and one for consumers, preceded by informed consent. The information was recorded in a survey sheet with an identification number for anonymity. The study variables were: • Linked to sellers:v Socio-demographic characteristics (sex; age; marital status: single, married, divorced, widowed; educational level: illiterate, primary, secondary and higher education; employment status: farmer, stockbreeder, retailer of other items, housewife);v Factors (other gainful activity, average daily income) influencing the sale of street drugs;v Sources of supply (local: wholesaler, relatives of the patients or outsiders: neighbouring countries) of street drugs;v Methods of storage of medicines (storage, after-sales storage);v Vendors' knowledge (good, average, none or poor) of the health risks of street drugs.• Consumer-related:v Socio-demographic characteristics (sex; age; marital status: single, married, divorced, widowed; educational level: illiterate, primary, secondary and tertiary; employment status: farmer, herder, reseller of other items, housewife);v Factors (reason for purchase, monthly income) influencing the consumption of street drugs;v Attitude towards street drugs (attendance at health facilities, regularity of drug purchase, results after taking the drugs, advice from a third party, verification of the expiry date); v Knowledge (good, average, none or poor) of the vendors on the risks of street drugs.At the end of the data collection, the analysis of the results was carried out with Epi data version 3.1 software for the creation of our database, and SPSS 19.0 software for data processing. The threshold of significance was set at p < 0.05.• Operational definitions: v Marital status: marital status under the law (single, married, divorced, widowed, common-law);v Grade level: refers to the highest level of education a person has successfully completed;v Illiterate: people who have not learned to read and write;v Primary: first level of education. These are all people who have learned to read, write and learn the basics of mathematics;v Secondary: all the courses received in secondary school and high school, culminating in the baccalaureate;v Higher: university education, post-baccalaureate;v Professional situation: situation related to a job, an income-generating activity;v Farmer: a person who carries out agricultural activities related to the land;v Breeder: a person who carries out activities related to the breeding of animals;v Reseller of other items;v Housewife: the one who does not have a monthly income or who is unemployed;v Risks: possible dangers or the occurrence of an unfortunate event; v Illegal sale: transfer of a drug by a seller outside the official circuit (authorized by law) to a buyer to satisfy a health need;v Expiry date: expiry date of the product. Adherence to expiry dates is essential. It may happen that drugs when they exceed their expiry date may change appearance in tropical climates and degrade into a toxic product.v Income: according to ECOM2 [16]:v low: monthly income < 152 €;v average: monthly income 152-456 €; v high: monthly income > 456 €.

3. Results

- 1. Sellers:• Socio-demographic characteristics

|

|

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

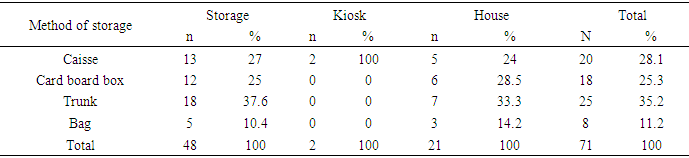

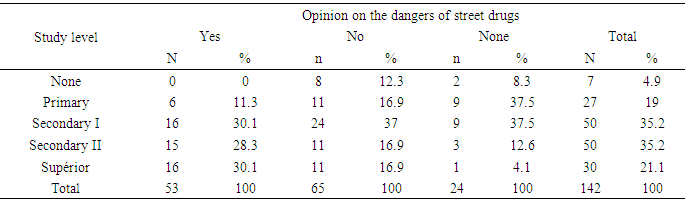

- The vendors interviewed in the four (4) boroughs were distributed as follows: Lumumba (17), Mvoumvou (7), Tié-Tié (20) Louandjili (27). This sample was mainly made up of male vendors (95.7%) with a secondary I school level. This male predominance was found in Mali in 2011 [6], but is contrary to those observed in Côte d'Ivoire where in 1997, this trade was female [14]. The results reported by our work on the level of study are similar to those observed in Brazzaville in 2005, which noted in its study that 99.1% of sellers were in school, while thesis work carried out in Mali in 2011 and Burkina Faso in 2003 reported respectively that 48% of sellers were not in school and the other a very low level of study [6-8]. In Cameroon, they had an above-average level of education [4], however, in Niamey the level of education was lower [4], as well as in Benin and Côte d'Ivoire where the level of illiteracy among vendors was very high [13, 14]. Among the vendors surveyed, 52.7% were exclusive street drug sellers compared to 47.9% who also carried out other activities. These results are partly similar to those observed in Mali where 46% of sellers were engaged in other activities [9]. Concerning the method of storage of medicines, nearly 37.5% of the sellers kept their medicines in metal trunks and the majority of these sellers (67.6%) stored their medicines in after-sales depots. These results are similar to those found in Congo Brazzaville [7]. Despite the average level of education of the sellers, they were unaware of the conservation standards recommended by the World Health Organization, which showed that there are many sources of supply for street medicines. 22.5% of the drugs sold were from outside the country and 29.In Mali, Abdou Idrissa reported that pharmacies were the frequent sources of supply [10] and in Cameroon, a study also observed that sellers of the illicit circuit partly obtained their supplies from authorized wholesalers [15]. This discrepancy with our results can be explained by the porosity of our borders. A similar observation was made in Dakar in 2006, where the absence of border barriers created an enabling environment for the illicit trade in medicines because they came from neighbouring countries (Gambia, Guinea Bissau) [11]. In our study, 87.3% (n=62) of sellers were prescribing and dispensing simultaneously; the main criterion taken into account was age (27.4%). This result is similar to the one found in Niamey reporting that 74.2% of sellers, although not knowing how to read or write, played both roles: prescriber and dispenser [10]. With regard to sellers' knowledge of the effect of light on medicines, 82.3% of sellers were unaware that light could influence the quality of medicines. These results differ from those found in Brazzaville, which reported that 46.1% of its sample claimed the sun decreased the effectiveness of drugs [9].In our study, we noted a female predominance among consumers, i.e. 60.6%. This result can be explained by the high number of housewives. The average age was 31±10.6 years. This is substantially similar to the one found in 2005 in Brazzaville [7]. Among the factors justifying the use of street drugs, we found as the main reasons for purchasing them: the low cost of street drugs, mentioned by 62.7% of consumers, followed by self-medication in 15.5% of cases and finally the sale of certain products by unit for 14.1% of consumers. A study on the factors determining the consumption of street drugs in urban areas in Cotonou [5] found similar results to those obtained in our study. Lack of financial resources and poverty could be crucial factors justifying the use of street drugs. These results are close to those found in Benin where 23.6% had an income of less than 50,000 CFA francs [8]. Among the 56.5% of consumers who do not attend health facilities, the practice of self-medication was mentioned by 77.2%. These results are higher than those observed in Benin, where 43% of subjects did not attend health facilities and 29% said that access to street drugs was easier [3]. We found that 46.5% of consumers bought the drugs after the advice of a salesman and 28% after the advice of a third person. Our results do not agree with those of Angbo-EffiKachi, who noted that 53.3% of cases, the purchase of drugs was influenced by those around them [5].In our study, 45.7% said that street drugs are not dangerous. Our results are in contrast to those of Benin, which reported 85% of subjects were educated (secondary level and above) and knew the risks of drugs [3]. With regard to information on the dangers of street drugs, for 57% of consumers surveyed, the most frequently cited source of information was "word of mouth". In Benin, a study noted that 90% of the messages that seemed convincing came from the media (television) [3]. Concerning the misuse of medicines, 57.7% of consumers had stated that this is a health hazard, the most frequently cited risk was digestive, particularly gastralgia i.e. 67.1%. These results are lower than those found in Ouagadougou, digestive disorders accounted for 39% of the cases encountered but did not specify them [8].

5. Conclusions

- This study shows that the sale and consumption of street drugs in Pointe-Noire remains a public health problem, reflecting the ineffectiveness of public authorities. This activity is mainly carried out by idle young people, sometimes with an average level of education, without scientific information that can protect equally young consumers without financial stability from danger. It therefore appears that several factors are at the root of this phenomenon, but the low cost of these drugs and the daily income of sellers are the major factors justifying the persistence of this illicit practice, which is destroying the profession of pharmacist. Poor storage of medicines, uncertain indications that sellers give to consumers and lack of knowledge among sellers about the risks associated with the illegal sale of medicines expose consumers to health risks. As a result, consumers' average knowledge of the dangers of street drugs indicates the need to increase awareness campaigns in order to improve their knowledge later on.

References

| [1] | Bourdillon F, Brucker G, Tabuteau D. traité de Santé Publique, chapter 19: politique du médicament (OMS). |

| [2] | Aide mémoire, N°338, Collectif. WHO. 2010. Rational use drug. |

| [3] | Abdoulaye I, Chastanier H, Azondekon A. Investigation of the illicit drug market in Cotonou (Benin). Med Trop 2006; 66: 573-6. |

| [4] | Pouillot R, Bilong C, Boisier P. Le circuit informel du médicament à Yaoundé et à Niamey: Etude de la population des Vendeurs et de la qualité des médicaments distribués. Bull Soc Path Exo 2008; 101 (2): 113-8. |

| [5] | Angbo-Effi O, Kouassi D P, Yao G H. A. Factor determining the consumption of street drugs in urban areas, Public Health 2011, vol. 23, No. 6, 2011/11-12, pages 455-464. |

| [6] | Halidou S M. Problem of the illegal sale of medicines in commune II of the district of Bamako (rail da)74651188. Pharmacy thesis. Faculty of Pharmacy 2012, University of Technical and Technological Sciences Bamako (Mali). |

| [7] | Kouala landa C, Le marché parallèle du médicament à Brazzaville. Medical Thesis. Faculty of Health Sciences 2005; n°694: -125p. |

| [8] | Saouadogo H. Study of the health risks associated with the use of drugs sold on the informal market in Ouagadougou. Pharmacy Thesis. Faculty of Pharmacy of Ouagadougou 2003; n°046:-152p. |

| [9] | Samake M. George Peter's assessment of the risks of contracting diseases due to the use of street drugs in Bamako. Pharmacy thesis. Faculty of Medicine, Pharmacy and Dontostomatology 2010; No.: -127p. |

| [10] | Abdou Idrissa H. Les médicaments de la rue à Niamey: Sales and quality control procedures for some anti-infective drugs. Pharmacy thesis. Faculty of Medicine, Pharmacy and Dontostomatology 2005; n°: -138p. |

| [11] | El Hadji MalickSy Camara: The illegal sale of drugs in the parallel market of "Keur Serigne bi". Mastery. CheikhAntaDiop University of Dakar 2006: -70p. |

| [12] | Amoussou J. La vente illicite des médicaments au Bénin. The case of the international Dantokpa market in Cotonou. ReMeD Round Table, Paris, 1999. |

| [13] | Legris C. Detection of counterfeit medicines by studying their authenticity. Pilot study on the illicit pharmaceutical market in Côte d'Ivoire. Pharmacy thesis. Université Nancy-I Henry-Poincaré, Nancy, 2005. |

| [14] | Aka E. The antibiotics market in Côte d'Ivoire: prospective study of prescription, impact of medical promotion. Thesis in Pharmacy, Felix Houphouët Boigny University, Abidjan, 1997. |

| [15] | Socpa A, Mballa J. Qualitative study on perceptions and risk behaviours in relation to the sale and consumption of the drug in Cameroon. Study report Ministry of Public Health. Rapport Coopération Française au Cameroun, Yaoundé, 2005. |

| [16] | Second Congolese household survey for poverty monitoring and evaluation (ECOM 2011). Ministry of Planning and Integration. Report of the QUIBB-ECOM2 2012 component; 1: 142. |

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML