-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2018; 8(2): 372-376

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20180812.04

Analysis of the Cold Chain in Routine Brazzaville Vaccination

Jean Bruno Mokoko1, Gildas Oball Mond Mwankié2, Ange Antoine Abena2, Jordelie Loumouamou2, Gontran Ondzotto1

1Brazzaville University Hospital, Faculty of Health Sciences, Marien Ngouabi University, Brazzaville, Congo

2Faculty of Health Sciences, Marien Ngouabi University, Brazzaville, Congo

Correspondence to: Jean Bruno Mokoko, Brazzaville University Hospital, Faculty of Health Sciences, Marien Ngouabi University, Brazzaville, Congo.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2018 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

This Background: Respecting the cold chain (CC) is essential in the quality and safety of vaccination. The purpose of this work was to determine the factors influencing the operation of the cold chain. Methodology: it was a cross-sectional and observational study. The strategy consisted, after random sampling, of conducting a survey of a sample of 91 vaccinating agents from 26 integrated health centers (IHC) distributed in the seven Socio-Sanitary District (SSD) of Brazzaville. The data was collected over an eight-month period based on an individual interview with the agents, observation, examination of the documents of the vaccination unit and the cold chain. These data were recorded on a survey sheet. As a result, the study found that 72% of staff were trained and retrained for the Expanded Program on Immunization, 73% of CSIs had normal refrigerators, and 63% of centers did not have their current temperature records. In the event of refrigerator failure or load shedding, 30.7% of IHC exposed vaccines to inadequate temperatures; 53.8% keep vaccines at the nearest center and 46.2% of centers link vaccines to other products. At 92.3% the source of energy was the current. Conclusion: It appears that the respect of the chain of cold is not effective. Capacity building of staff and equipment is needed to make vaccination safer.

Keywords: Cold Chain, Vaccination, Integrated Health Centers

Cite this paper: Jean Bruno Mokoko, Gildas Oball Mond Mwankié, Ange Antoine Abena, Jordelie Loumouamou, Gontran Ondzotto, Analysis of the Cold Chain in Routine Brazzaville Vaccination, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 8 No. 2, 2018, pp. 372-376. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20180812.04.

1. Introduction

- The ability of an immunization program to provide immunization services to the entire target population is a question of thoroughness, especially in the cold chain (CC). Mastery of the CC therefore represents a growing public health issue, as more and more new temperature-sensitive vaccines are on the market [1, 2]. In addition, evaluations conducted from 2001 to 2003 in Africa show that many countries, especially those in the tropics, need to improve their vaccine management system [3]. In 2014, in the Statement on the Comprehensive Framework for Effective Vaccine Management (EVM), WHO and UNICEF revealed that of 20% of health centers in low-income countries, 78% had cold chain equipment either non-functional or with obsolete technology, which would lead to a breakdown of the CDF and the ineffectiveness of vaccines [4]. Compared to WHO standards, only 14% of low-income countries have met the criteria for temperature control in the cold chain [4]. In Congo, for example, the need to know the status of vaccine storage equipment within the recommended temperature range is necessary. The aim of this work was therefore to describe the state of the cold chain and the storage conditions of the vaccines.

2. Materials and Methods

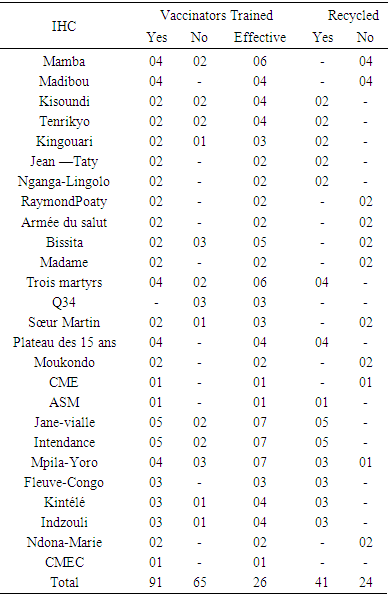

- It was a cross-sectional and observational descriptive study, from January 11 to August 22, 2015, a period of 8 months, preceded by a one-month pre-survey. The study was carried out in the Makélékélé CSI (Madibou, Jean Taty, Tenrikyo Mamba, Kingouari, Kisoundi, Poaty Raymond, Ngagalingolo), Bacongo (Bissita, Madame), Poto Poto (Three martyrs, Q34, sister martin), Moungali (Moukondo, Plateau des 15 ans, ASM, CMSE), Ouenze (Jane Vialle), Talangai (Mpila Yoro, Kintele, Intendance, CMEC) and Mfilou (Indzouli and Ndona Marie). The target population consisted mainly of the vaccinating agents of the different CSIs. Sampling was done by random selection in the 7 selected health districts (SSD). The size of our sample was 91 vaccinators distributed in 26 CSI out of the 52 in Brazzaville. The included IHC were those with a fixed vaccination center, those with a functional cold chain and vaccinating agents operating at the health centers. The data were collected using a survey card, observation, exploitation of the documents of the vaccination unit and the cold chain in the IHC.The variables studied were:• state of the cold chain:o Vaccine storage conditions: temperature control, temperature sheet present and updated, control pellet on vials, use of thinner, arrangements made in case of power failure;o Vaccine handling at the IHC level: assessment of the availability of vaccines in the refrigerator, verification of the existence of a compartment reserved for other products;o CC material management: the type of preservation equipment, the current status, the energy source, the rate of maintenance of vaccine storage equipment, the presence of a technician and the availability of spare parts. spare parts;• training of vaccinating agents on the CC: grade of the head of center and the head of the CC; number of agents trained and recycled by the EPI for ITUC and the knowledge of vaccinating agents on the CC.Data entry and processing were done CSPro 4.0, Word 2010. The statistical analysis of the data was done by the uni-varied method (calculation of%) and a quotation of the points to treat the data, which allowed a qualitative assessment of the services and the results.Operational definition:• Routine vaccination: the act of introducing an external agent into the body daily in a fixed center according to a given program, which varies from one center to another.• Cold chain: all the equipment and people responsible for keeping vaccines at a low temperature during transport, from the manufacturer to the vaccination sessions.

3. Results

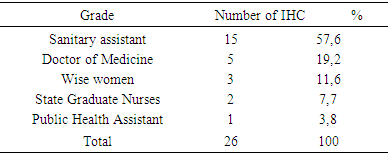

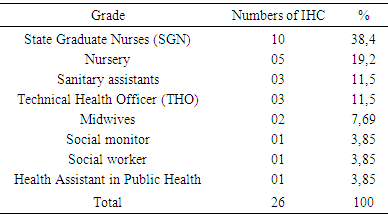

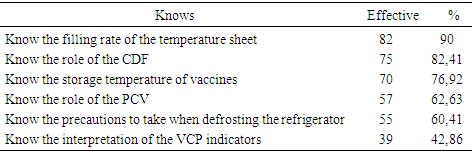

- Condition of the cold chain at IHC1. Vaccine storage conditionsDuring the study, 53.9% of IHC used a thermometer while 46.1% had a thermostat for temperature control of refrigerators. A temperature control sheet was available in nineteen IHCs, 73.1% and 26.9% of IHC did not have one; updating the cards in the IHCs that had them were regular. IHC all used diluents from the manufacturer. All vaccines observed in our study carried a vaccine control pellet. However, in case of a power failure to keep the vaccines, fourteen IHCs, 53.8%, kept the vaccines at the nearest IHC, while eight other IHC (30.8%) kept the vaccines in neighboring private dwellings (unadapted fridge) and 4 other IHC 15.4% were freezing the accumulators.2. Vaccine Handling at IHCVaccines were not available in refrigerators (vaccine storage) according to standards. In fact, in six IHC, storage was disordered (23.1%) and in three IHC (11.5%) the compartments were saturated. However in the seventeen IHC remaining vaccines classified and ordered.3. CDF Material ManagementThe equipment of the CDF consisted of: refrigerator + accumulator vaccine carrier or cooler in 80.8% of IHC and freezers + accumulator door vaccine / cooler in five IHC are 19.2%. This equipment was functional in nineteen IHC 73.1%; broken down in four IHCs are 15.4% and out of service in 3 IHCs are 11.5%. The rate of maintenance of this equipment varied according to the CSI. It was monthly in 18 CSI's 69.2%; weekly and daily in 8 IHC are 30.8%. In twenty-four, 92.3%, the main source of energy was electric current, and two IHCs had a generator in addition to this energy. No CSI used oil as energy. All twenty-four IHCs had one source of energy. However, to cope with brownouts, nineteen IHCs (73.1%) had a voltage regulator. Only eleven IHCs, 42.3%, had a technician for repairs. In 84.6% of IHCs were twenty-two, CC fuels and spare parts for equipment were not available, they were found in only four IHCs, or 16.4%. II. Training and knowledge of vaccinating agents operating in IHC:

|

|

|

|

4. Discussion

- The main objective of our study was to analyze and describe the condition of the cold chain in routine immunization. Insufficient capacity in the cold chain greatly aggravates vaccine shortages [4]. The results of this study reveal dysfunctions that call into question the quality of vaccines. The use of the thermostat is more reliable, it allows to regulate the internal temperature of the refrigerator and can be adjusted at any time as in the study by Talani [5]. Our results report that only 46.1% of refrigerators were equipped with an external thermostat. These results are weak compared to those of Barber [6] who found refrigerators with 93% external thermostat. The storage temperature of the vaccines is not recorded daily in all the centers surveyed. Indeed, in 26.9% of the cases the CSI do not have a temperature card and 63% of the cases do not update their temperature sheets. Our data are similar to those of Barber in Spain and Boda [6, 7] who report that 75% of the cases were not updated. These results lead us to question the reliability of the temperatures at which vaccines are stored. This negligible state of affairs may be detrimental to vaccination as suggested by Jeremijenko [8] who consider this lack of rigor in vaccine storage as a common practice in developing countries. The use of VVM is satisfactory and the vaccines used in the centers surveyed have VVM. All the CSIs surveyed use the manufacturer's diluents, which they keep at the same temperature as the vaccines. The present study shows that 30.7% of CSIs keep vaccines in neighboring homes at unsuitable temperatures. Under these conditions, the notion of temperature control is no longer taken into account. Our results show that 15.4% of CSIs freeze accumulators corroborate with data from Moukala, which reports a rate of 16.7% [9]. This attitude is explained by the poor quality of the electric current, the lack of stabilizers in some CSI (65.4%) and regular maintenance. Although 53.8% of CSIs keep vaccines in the nearest CSI, these inadequate provisions do not guarantee the quality of the vaccine. In Algeria, a study by Nizar reports that the inefficiency of vaccines had resurfaced cases of measles [10]. In 63.4% of the cases the storage of the vaccines in the CSI is not optimal, 23.1% have a disorderly storage and 11.5% have saturated compartments. The storage of vaccines in refrigerators does not take into account the thermosensitivity of vaccines, and all vaccines are subjected to the same temperatures. These inadequate storage spaces prevent the flow of air. These results are in agreement with those observed by Berhane in Ethiopia where 63% of centers had an inadequate arrangement of vaccines in the refrigerator [11]. In fact, vaccines must be stored in the main compartment at a temperature between +2 and +8 ° [12, 13]. However, they are kept in the freezer compartment which does not correspond to WHO recommendations. Such is the case of the "Salvation Army" center, where Oral Polio Vaccine (OPV) has been stored until it is frozen in the freezer compartment while freezing inevitably destroys the vaccines [14]. Our survey reveals that 46.2% of centers have in their refrigerator a compartment reserved for other products such as: samples and / or products from the laboratory as well as bottles of water and drink. As a rule, samples should never be placed in refrigerators or coolers containing vaccines [15]. Drinks and other products are strictly prohibited because they prevent air from circulating and have a high risk of vaccine contamination, which destroys the product or reduces its effectiveness [13]. Our results corroborate the data of Baber [6], who found food stored in the vaccine refrigerator in 32% of cases. These practices reflect the lack of knowledge of vaccine storage standards.The equipment in the cold chain of the CSIs surveyed complies with the WHO standards and are of the type with a long shelf life of cold. 80.7% of CSIs have an EPV refrigerator and 19.2% have a freezer. Accumulators and vaccine doors are available. Our results show that the CSIs studied are better equipped than those studied by Mounkala [9] on the one hand who found only 47.8% of the CSI with equipment and on the other hand more satisfactory than those reported by Barber who point out that 100% of the refrigerators were domestic (therefore unprofessional for the CDF) [6].The equipment is in good working order in 73.1% of the centers. By contrast, 15.4% of refrigerators are out of service due to lack of electricity in their areas of implementation, and 11.5% of refrigerators have been out of order for more than three months. The profile of our results is similar to that observed by Grasso [16] who reports that in 76% of the cases the refrigerators were functional. We note a predominance for the electric current is 92.3% of CSI surveyed. This explains the fact that all the health centers are equipped with equipment operating in the current, but these are subject to frequent breaks of electricity and sometimes of long duration. At CSI Sister Martin, the frequent breakage of electricity has led officers to use ice cubes instead of accumulators. Consequently the temperatures obtained are outside the norms (+15 °C). Our results are close to Barber's data [6], which point out that 70% of refrigerators were subject to power outages. This is the main cause of malfunctions noted in the storage and handling of vaccines. Our investigation reveals that 65.4% of CSIs do not have power stabilizers, while the latter plays an important role in protecting equipment against electrical fluctuations. The rate of maintenance varies according to the equipment used. For this, 69% of the centers perform a monthly maintenance of the equipment, and 15.4% of the centers realize it daily. The refrigerator must be maintained and cleaned regularly. Maintenance reduces the risk of equipment failure, and repairs are used to restore defective equipment [17]. In terms of maintenance personnel, 42% of centers have an external technician for equipment maintenance, which refers to the requirements of manufacturers' manuals for the maintenance of their products without the required qualifications. The lack of fuel (oil) in the CSIs surveyed is very remarkable, 84.6% of centers lack available fuel for the simple reason that most centers use electricity as energy. Although mixed, the oil portion of these refrigerators no longer works in most centers and for some because of the lack of financial means for the purchase of fuel. Only 15.4% of centers have spare parts available (wicks). The agents working in the CSI are for the most part health professionals, of the 26 CSIs surveyed, 19% are held by doctors, 58% by health assistants, 8% by FDI and 12% by midwives. EPI managers are mostly nurses (38.4%), nursery nurses (19.23%) and health assistants (11.54%). Our study notes the presence of doctors and other categories of health workers, which is contrary to the Haghou results in Djibouti or in 2006, it found only FDI [18] and those of the Ethiopia or according to Berhane the majority of the staff had no qualification [11]. Our results, report that 71.4% of vaccinating agents have attended at least one training for the EPI. These results are similar to those found in the report on the training of middle-level managers on the EPI (73%) in 2008 [3]. In addition, 96.2% of CSIs have on average one officer trained in the field of EPI. This is causing low performance because, according to Barber, even if we have a high-performance equipment, the cold chain remains ineffective if the staff does not handle the vaccine or equipment properly [6]. Our study shows that 82.4% of the agents know the role of the CDF and 82% have the mastery on the filling rate of the sheet of temperature, even if a negligence was observed in the holding of these sheets. 62.63% know the role of the control tablet, while 42.86% manage to interpret the indicators of the VCP, its use as a control element of the cold chain is still shy. 76.92% are aware of the storage temperature of the vaccines and finally, with regard to the precautions to be taken when the refrigerator is defrosted, 60.4% of the agents are in a position to take adequate measures.

5. Conclusions

- The study of the problem of the cold chain in routine vaccination in Brazzaville, allowed us to assess the behavior of agents in the handling of vaccines before and after vaccination and the condition of the equipment. It places particular emphasis on conservation and storage issues that reveal a logistical system of obsolete vaccination which would undermine the success of the EPI. These shortcomings stem from the lack of investment in equipment, human training and neglect in the strict application of standard policies in vaccine management. Strengthening and optimizing immunization chains involves capitalizing on the four key factors of the comprehensive framework for Effective Vaccine Management (EVM) [4]. In order to promote a continuous improvement of the chains of vaccination as well as obtaining a total and equitable vaccination coverage. At the end of this study, we suggest:• At the central level:o Organize supervision and training for the maintenance and maintenance of CDF in all IHCso Develop and disseminate a user guideo Allocate operating credits of the CDF to enable maintenance and pay the labor• To health staff:o Regularly fill in the temperature check sheetso Respect the equipment and materials of the CDF

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML