-

Paper Information

- Next Paper

- Previous Paper

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2018; 8(7): 145-154

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20180807.05

Color Doppler Ultrasonography Changes of Portal Circulation after Band Ligation of Esophageal Varices in Egyptian Patients with Chronic Liver Disease

Samia Masoud1, Wafaa M. Elzefzafy1, Alya Elnaggar2, Ola I. Saleh2, Asmaa Ibrahiem1

1Department of Tropical Medicine, Faculty of Medicine for Girls, Al-Azhar University, Egypt

2Department of Radio-Diagnosis, Faculty of Medicine for Girls, Al-Azhar University, Egypt

Correspondence to: Samia Masoud, Department of Tropical Medicine, Faculty of Medicine for Girls, Al-Azhar University, Egypt.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2018 The Author(s). Published by Scientific & Academic Publishing.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

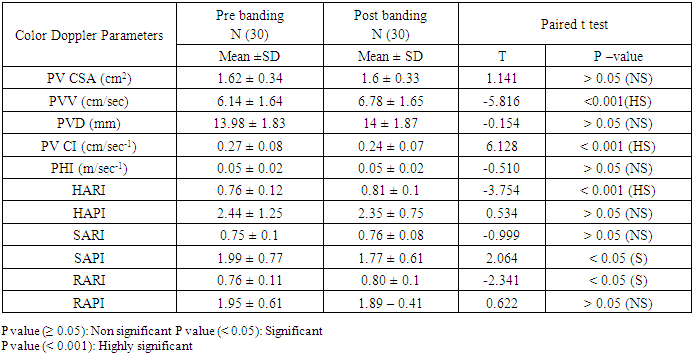

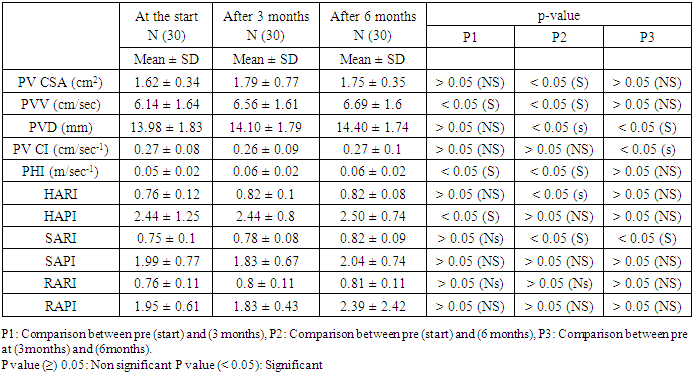

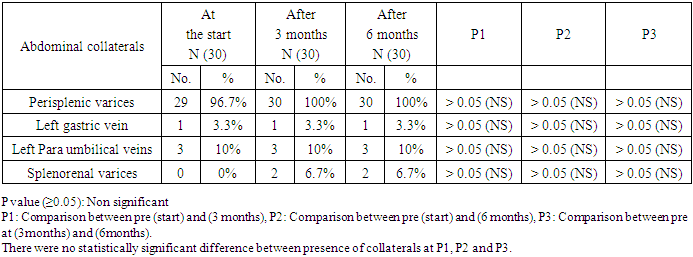

Chronic liver disease (CLD) can result in portal hypertension (PH), the key event leading to formation of portosystemic collaterals including gastroesophageal varices (EVs). Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) is recommended as the first line investigation at the initial diagnosis. Doppler ultrasound is alternative, non-invasive parameter for surveillance of EVs. Aim of the work: was to study the Color Doppler Ultrasound changes of portal circulation in Egyptian patients with chronic liver disease after band ligation and its role in early detection of newly developed Varices. METHODS: This is prospective study conducted on 30 patients with (CLD) subjected to band ligation of (EVs), and 15 subjects with despepsia were chosen endoscopically without varices and sonographically free as a control group. upper endoscopy, CBC, liver and kidney function tests, Histopathological examination of upper endoscopic biopsies, abdominal and Color Doppler ultrasound (CD US) were done at the start of the study and reevaluation by CD US was done at 0, 3 and 6 months post band ligation sessions. Results: There was decrease in number of EVs columns and grading after 3 and 6 months with increase in number of cases of severe gastropathy after band ligation, Splenic artery RI and PI, Hepatic artery RI and PI and Renal artery RI and PI were good predictors for (PH), and (EVs). There were no statistically significant difference between presence of collaterals pre banding and after (3 and 6 months) post banding by CDUS. Conclusion: Portal hemodynamics using CD UScan serve as an important tool in the follow-up of patients undergoing endoscopic intervention as in endoscopic variceal ligation.

Keywords: Portal hypertension (PH), Gastroesophageal varices (EVs), Color doppler ultrasound (CD US), Endoscopic Variceal Band ligation (EVBL)

Cite this paper: Samia Masoud, Wafaa M. Elzefzafy, Alya Elnaggar, Ola I. Saleh, Asmaa Ibrahiem, Color Doppler Ultrasonography Changes of Portal Circulation after Band Ligation of Esophageal Varices in Egyptian Patients with Chronic Liver Disease, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 8 No. 7, 2018, pp. 145-154. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20180807.05.

Article Outline

1. Introduction

- The primary prevention of bleeding from esophageal varices is a major challenging therapeutic goal requiring early screening of esophageal varices. The mortality rate of the first bleeding episode patients with esophageal varices (EVs) reaches up to 40%, EVs present in 40% of patients with compensated and in 60% of those with decompensated liver cirrhosis [1].EGD still remains the best way to diagnose and evaluate esophageal and gastric varices, Endoscopic Variceal Band ligation (EVBL) has been shown to be effective, safe and easy procedure in eradicating esophageal varices, initial obliteration with disappearance of signs of impending rupture was achieved in all patients without critical complications or mortalities, however worsening of grade of congestive gastropathy & grade of ascites were obvious after follow up, However, it is an invasive procedure that requires significant hospital resources including experienced staff and hospital stay, Non-invasive methods that can be reliably used to predict the presence of EVs are urgently needed in clinical practice [2].EVBL has been shown to be effective, safe and easy procedure in eradicating oesophageal varices, initial obliteration with disappearance of signs of impending rupture was achieved without critical complications or mortalities, however worsening of grade of congestive gastropathy & grade of ascites were obvious after follow up [3].CD US is alternative, non-invasive parameters for surveillance of EVs in patients with liver cirrhosis. It is used to correlate the presence or absence of EVs and its size. Many parameters indicating the presence of portal hypertension could be identified non-invasively, including the presence of collateral vessels, splenic enlargement, ascites, change in the PV parameters (e.g. increase in diameter, increase in the CI), increase in hepatic and splenic arterial resistance indices. These parameters were proposed to be useful in the clinical monitoring of patients with cirrhosis and PH and early detection of EVs [4].

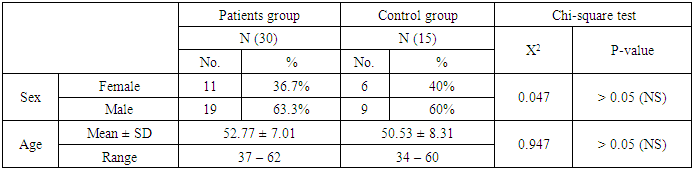

2. Patients and Methods

- This is was prospective study conducted on 45 patients admitted at Al-Zahraa University Hospital, Tropical Medicine Department, 30 patients with chronic liver disease and esophageal varices subjected to band ligation, and 15 control subjects suffering from dyspepsia with no varices. Both groups were matched as regard age and sex, the study was conducted during the period from November 2015- November 2017.Inclusion criteria: Patients with chronic liver disease (child A & B) and patients with EVs ≥ grade II.Exclusion criteria for the patients group included: Patients with fundal varices received beta-blocker, NSAIDs or diuretics within the last 15 days, patients with thrombosis of the portal or splanchnic vascular tree, history of upper GI hemorrhage within 3 months, previous sclerotherapy, hepato cellular carcinoma, TIPS or liver transplantation.After informed consent all patients and control subjects were subjected to the followings:v Clinical examination.v Laboratory investigations including:A. Complete blood picture (CBC): Which was done on Sysmex (Germmany).B. Liver function tests: Which were done on Cobas c311 auto analyzer (Germmany). Using Roch reagent kits.C. Hepatitis sero markers: Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and Hepatitis C virus antibody (anti HCV) were measured by Enzyme linked immune sorbent assay (ELISA) technique according to Abbott laboratories and bilharzial antibody titre by indirect haemoagglutination test.v Endoscopic examination: -All patients underwent upper gastrointestinal endoscopy for assessment of esophageal and gastric varices using properly disinfected Pentax videoscope. Esophageal varices were graded from I to IV using Paquet grading system. Band ligation for EVs, Repeated endoscopic examination after 3 and 6 months post banding and comment on the appearance of new varices for the patients group was done.v Histopathological examination of upper endoscopic biopsies.v Radiological investigations:A) Abdominal ultrasound was done for all cases by Toshiba machine using B-mode longitudinal and transverse scans for assessment of liver (size, echogenisty and presence of focal lesions), longitudinal spleen diameter, Portal vein diameter (PVD), cross sectional area (CSA) and presence of ascites. Normal PVd <10 mm with (20-30%) increase with food and respiration.B) Pre and post band ligation CD US at the start of the study and after 3 and 6 months were done for measurement of:1. Portal vein main velocity (PVV).2. Portal Vein congestive Index (PV CI).3. Portal Hypertensive Index (PHI)4. Hepatic Artery Resistive Index (HARI) and Hepatic Artery Pulsatility Index (HAPI).5. Splenic Artery Resistive Index (SARI) and Splenic Artery Pulsatility Index (SAPI).6. Renal Artery Resistive Index (RARI) and Renal Artery Pulsatility Index (RAPI).7. Presence of collaterals.

3. Statistical Analysis

- Data were collected, coded, revised and entered to the Statistical Package for Social Science (IBM SPSS) version 20. The data were presented as number and percentages for the qualitative data, mean, standard deviations and ranges for the quantitative data with parametric distribution and median with inter quartile range (IQR) for the quantitative data with non parametric distribution.The comparison between two independent groups regarding quantitative data with parametric distribution was done by using Independent t-test.The confidence interval was set to 95% and the margin of error accepted was set to 5%. So, the p-value was considered significant if < 0.05.

4. Results

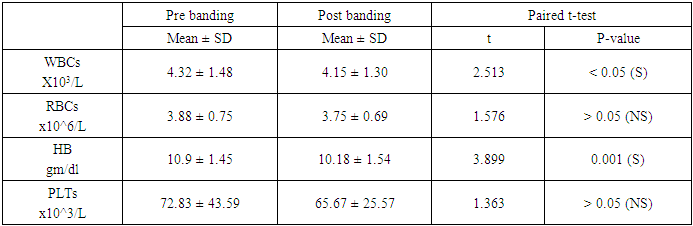

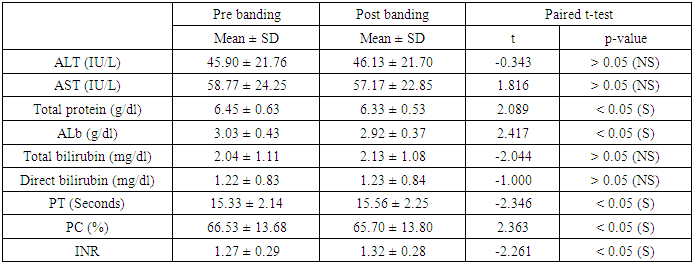

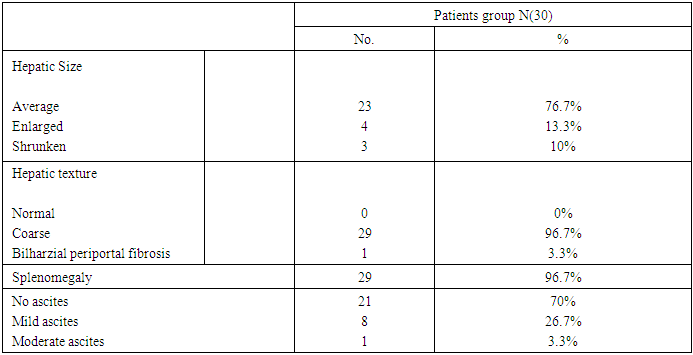

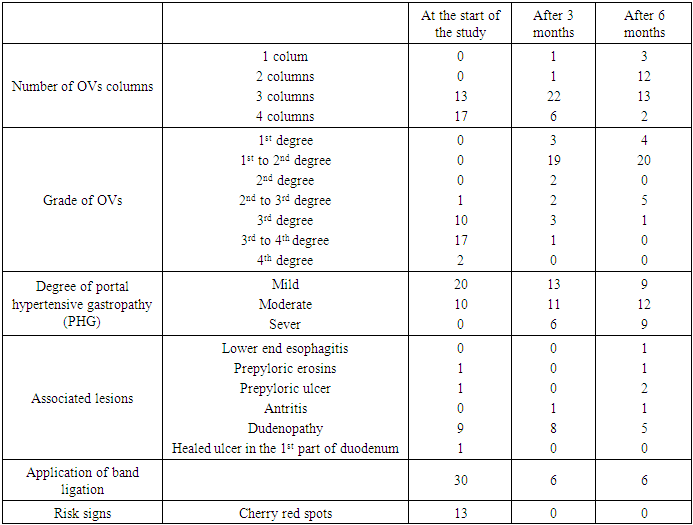

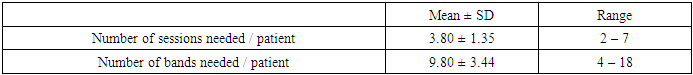

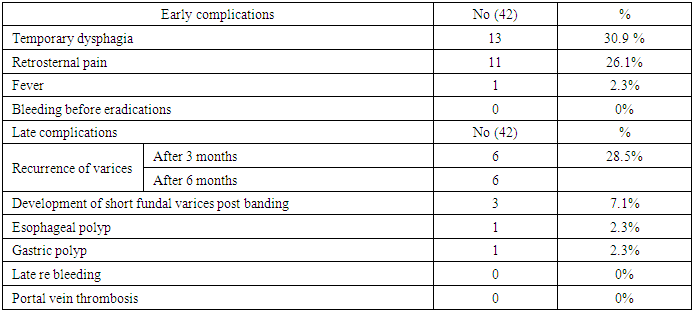

- The results and data were collected and analyzed in tables 1-11 and figures 1-9.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

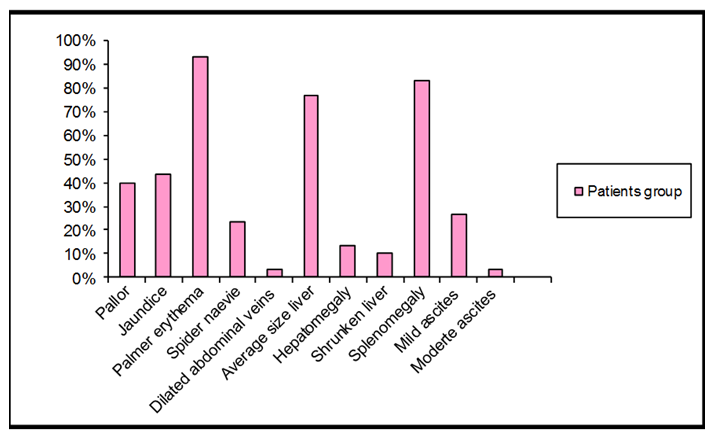

| Figure 1. The main signs among the patients group |

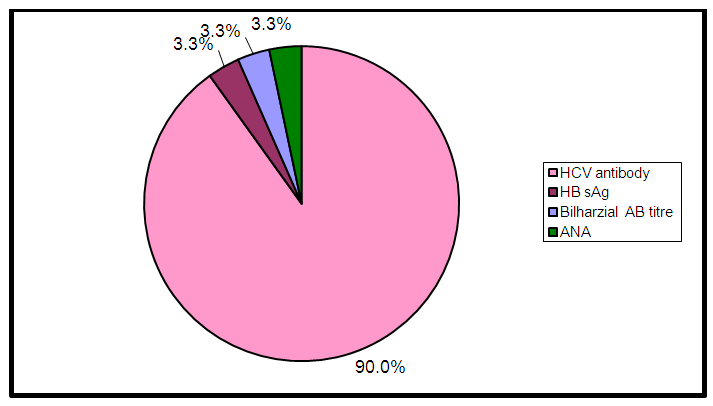

| Figure 2. Distribution of hepatitis markers, bilharzial antibody titre and ANA in the patients group |

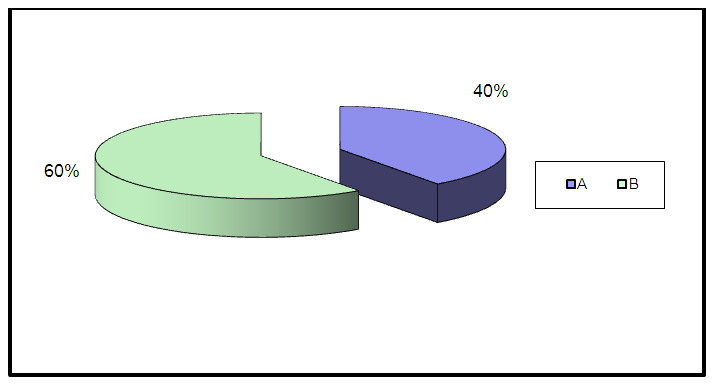

| Figure 3. Child's – Pugh Classification among the patients group |

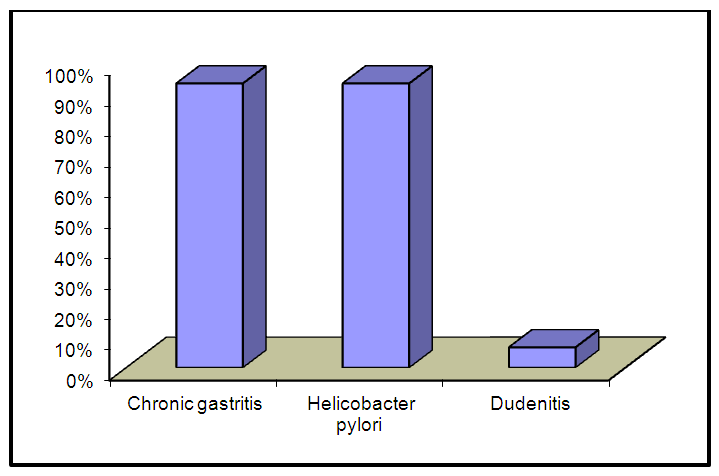

| Figure 4. Histopathological findings of upper endoscopic biopsies in the control group |

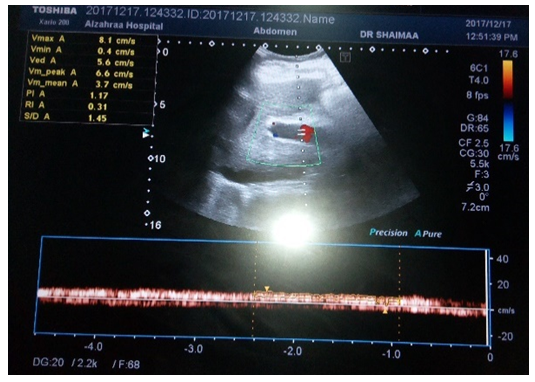

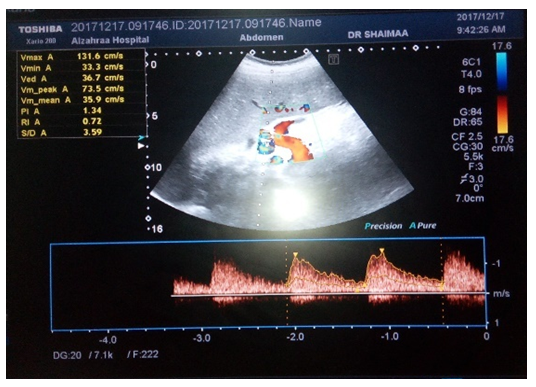

| Figure 5. CD US of PVV(3.7cm/s) |

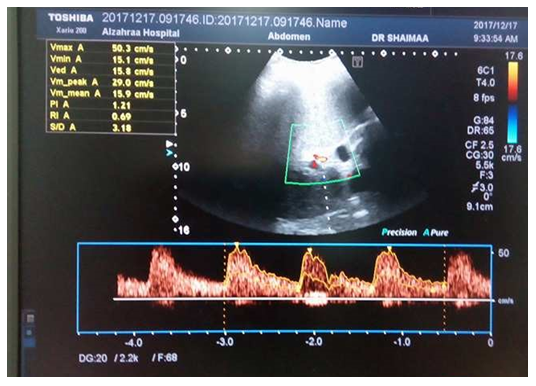

| Figure 6. CD US of HARI (0.69) |

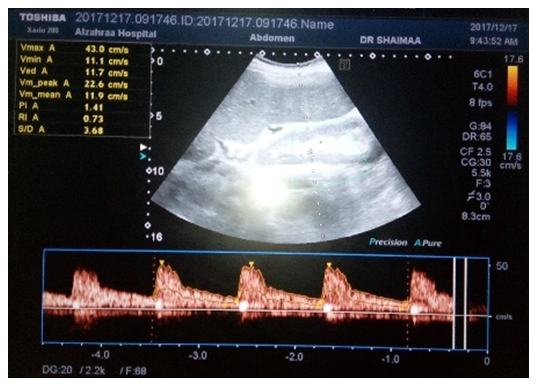

| Figure 7. CD US of SARI (0.69) |

| Figure 8. CD US of RARI (0.69) |

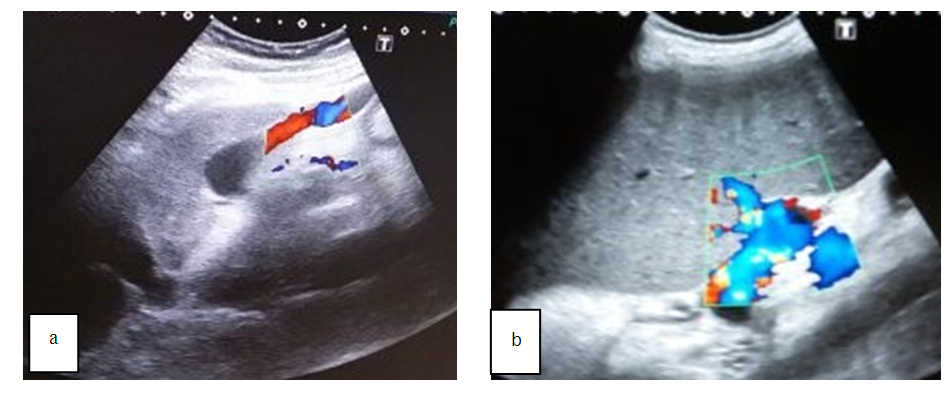

| Figure 9. CD US of dilated collaterals a) recanalized Left paraumbilical Vein and b) prisplenic varices |

5. Discussion

- EVBL has become the treatment of choice for bleeding of esophageal varices which is the most common complication of liver cirrhosis and portal hypertension [5]. Although generally considered to be safer than endoscopic sclerotherapy. Numerous complications of esophageal band ligation include retrosternal pain, rebleeding, esophageal perforation, mesenteric vein thrombosis, altered esophageal motility, septic complications resulting from bacteremia and esophageal stenosis [6].CDUS examine the haemodynamics of abdominal vessels including the hepatic and portal system. Doppler parameters are suitable substitute for the invasive current gold standard for measuring hepatic venous pressure gradient and assessing portal hypertension. Predicting the grade of varices by non invasive methods at the time of diagnosis is likely to predict the need for prophylactic beta blockers and band ligation as treatment for the varices [7].As regard abdominal ultrasonographic findings of the studied groups, there were highly significant increase of coarse liver, splenomegaly, dilated portal vein pre banding in the patients group and this in agreement with [8] who reported that these findings were highly significantly increased in patients with varices.Splenomegaly is a well-known imaging sign of portal hypertension that is caused by both passive congestion and hyperplasia. When portal vascular resistance is increased, a reduction in portal blood flow and stagnant flow in the spleen might be expected. On the contrary, when splenic inflow increases, it aggravates PH [9].In the present study histopathological examination of endoscopic biobsies in the control group revealed that 14 patients had chronic gastritis due to H pylori infection and 1 patient had dudenitis and this in agreement with [10].Our study demonstrated that 13 patients (43.3%) had EVs with cherry red spots before banding which disappear completely after 3 months post banding.In the present study there were complete obliteration of the varices by EVL and this in agreement with [11] who reported that the overall outcome of EVL was the eradication of oesophageal varices.After band ligation our study revealed decrease in grade of EVs reached 1st to 2nd degree in 19 patients after 3 months, 20 patients after 6 months and this in agreement with [12].Our study revealed increased number of cases with severe PHG which reflects the increase of PH after EVL. This results in agreement with [13] who reported that EVL eradicate EV with less complications and a lower re-bleeding rate, but at the same time eradication was associated with more frequent development of PHG, although [14] reported that despite the worsening of PHG and the development of fundal varices, there is no change in portal pressure with either sclerotherapy or EVL.Our results demonstrated that the number of sessions and bands needed per patient were (2-7) sessions and (4-18) bands in 6 months while [15] reported that during the technique of EVL, we used an average of 3-9 bands /session in early ligation then fewer bands in subsequent sessions and the number of sessions were more than 4 depend on number of columns and grade of EVs.In our study, the early reported complications of band ligation were temporary dysphagia in (30.9%), retrosternal pain in (26.1%), fever in (2.3%) in the patients group, while later complications after banding were fundal varices in (7.1%) and polyp (1 esophageal and 1 gastric polyp) in (4.6%).[16] found that no serious complications resulted from variceal ligation. Transient retrosternal pain, fever and dysphagia developed in (18%), (7%), and (4%) of the patients, respectively. Post-ligation variceal ulcers developed in 36 patients (80%) one week after the first session of ligation they were generally superficial.Our study reported that the incidence of variceal recurrence after obliterations was (28.5%) after 6 months. Similar results were reported by [17] where recurrence occurred in (22%) of cases during a mean follow up of 13 months.[18] reported that after endoscopic band ligation, esophageal varices recurred in 45% of cases. They concluded that extrahepatic portal hypertension and a greater size of varices lead to the statistically significant early recurrence of esophageal varices after endoscopic band ligation.In the present study, the PVD was highly significantly increased in patients with varices as compared with the control group. This was in agreement with [19] and disagree with [20] who concluded that the PV diameter may be affected by the development of portosystemic collaterals and noted that PV dilatation may occur in the absence of portal hypertension e.g. in response to huge splenomegaly or acute PV thrombosis so normal caliber of PV cannot exclude PH.Our study revealed that highly significant difference in PVD between patients and control groups. These results in agreements with [21]. Also [20] reported that patients with cirrhosis having esophageal varices, PVD and PVV of (13.8 ± 2.42) and (13.25 ± 3.66) were highly suggestive of presence of EVs.Our study revealed that statistically highly significant difference in PV CSA and CI between the patients group and the control group and this in agreement with [22] in a study of 72 patients of cirrhosis.[23] approved the value of measuring portal hemodynamics and stated that PVV is a good parameter to reflect the portal pressure gradient and useful for the diagnosis of PH. Therefore, the portal hemodynamics is very helpful in the assessment of the real status of cirrhosis, and should be proposed for cirrhosis staging.In the present study there were highly significant decrease in PVV in the patients group in comparison to the control group and this was in agreement with [24].The mean PVV in cirrhotic patients is relatively low compared with that in healthy subjects because of increased intrahepatic vascular resistance (outflow resistance) and this was in agreement with [25].Regarding the PV CI [26] and [21] in their study that compared the portal hemodynamics by using CDUS suggested the importance of the CI in reflecting the pathophysiological hemodynamics of the portal venous system in portal hypertension.Our study revealed that there were highly significant increase in PV CI of the patients group this in agreement with [27] and [28] who found that PV CI was significantly higher in cirrhotic patients with portal hypertension and also, [29] demonstrated significant increase in the PV CI in cirrhotic patients than normal subjects.Our study reported that portal hypertension index is elevated in the patients group and this agree with [21] and [28].Our study revealed that HAPI increase in the patients group with esophageal varices with statistical significance and this was in agreement with [29] but they reported that HAPI was the only parameter which had a higher value in patients with EVs compared with those without EVs (1.72 ± 0.44) versus (1.55 ± 0.31); however, on the multivariate analysis, this variation did not reach statistical significance.Our results denoted that hepatic artery resistance index (HARI) and the splenic artery resistance index (SARI) were highly significantly elevated in patients with varices in comparison to those without and this was in agreement with Sakr et al., (2011).Renal Artery Resistive index increased in the patients group in comparison to the control and this was in agreement with (30) who reported that RARI is 70% probability for existence of EV and more accurate in the prediction of EV.Our study revealed that there were highly significant increase in RARI in the patients group with esophageal varices and this was in agreement with 31 who reported that (RARI) is a good prediction for the presence of esophageal varices (70%).In our study the PVV increased following variceal obliteration from (6.14 ± 1.64) to (6.78 ± 1.65) with highly significant difference and this was in agreement with 32 who found that slight increase in the mean velocity after EVL suggesting that band ligation may have a tendency to increase portal blood flow to the liver and the stomach.The PV CI showed a highly significant drop after obliteration from (0.27 ± 0.08) to (0.24 ± 0.07) and this was in agreement with 31, although multiple response analysis of the PV CI along the follow up period showed no significant alteration.Our study revealed that there were a statistically significant increase of PV CSA in P2 significant increase in PVD in P and in P 3 and significant increase of PV CI in P3 and this disagree with [23] who concluded that no difference in PVD, CSA and CI of the PV before banding and after 6 months from band ligation of varices.Our study revealed that there were statistically significant increase in the PVV in P2 and P3 and this disagree with [24].In the patients group before band ligation, our study demonstrated that out of 30 patients, 29 had perisplenic collaterals, 3 had left para umbilical veins and 1 had left gastric vein detected by CD US and this in agreement with [33] who reported that abdominal porto-systemic collaterals were presented in roughly one third of patients with liver cirrhosis.After band ligation the number of patients had perisplenic collaterals increased to 30 patients and 1 patient developed lienorenal varices with no change in number of patients had left para umbilical veins or left gastric vein indicating aggravation of PH and this in agreement with [33].

6. Conclusions

- Doppler ultrasound is a noninvasive and accurate modality for evaluation of the liver and liver vasculature and has no adverse effects.Portal hemodynamics using Color Doppler Ultrasound can serve as an important tool in the follow-up of patients undergoing endoscopic intervention as in endoscopic variceal ligation.The accuracy of Doppler US for diagnosing changes in portal flow velocity and US correlation with the presence or absence of esophagogastric varices leads to fewer endoscopy indications.Splenic artery RI and PI, Hepatic artery RI and PI and Renal artery RI and PI are good predictors for portal hypertention and esophageal varices.Number of cases with severe portal hypertensive gastropathy (PHG) indicating increase PH after band ligation.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML