-

Paper Information

- Paper Submission

-

Journal Information

- About This Journal

- Editorial Board

- Current Issue

- Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Us

American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences

p-ISSN: 2165-901X e-ISSN: 2165-9036

2017; 7(3): 156-164

doi:10.5923/j.ajmms.20170703.09

The Relationship between Caring for Pets and the Two-Year Cumulative Survival Rate for Elderly in Japan

Tanji Hoshi 1, Maasa Kobayashi 2, Naoko Nakayama 2, Miki Kubo 3, Yoshinori Fujiwara 4, Naoko Sakurai 5, Steve Masami Wisham 6

1Tokyo Metropolitan University Emeritus Professor, Japan

2St. Luke’s International University, Japan

3Teikyo Heisei University, Toshima, Tokyo, Japan

4Tokyo Metropolitan Health Promotion Institute, Japan

5Tokyo Jikei Medical School, Japan

6Anicom holding Co Tokyo, Japan

Correspondence to: Tanji Hoshi , Tokyo Metropolitan University Emeritus Professor, Japan.

| Email: |  |

Copyright © 2017 Scientific & Academic Publishing. All Rights Reserved.

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution International License (CC BY).

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

BACKGROUND: The relationship between subjective health evaluations and survival rates among the elderly has been shown to be highly valid by many studies. There have been, however, no studies reported on the relationship between caring for a pet and survival rates among the elderly worldwide. PURPOSE: The main purpose of this study is to investigate the relationship between caring for pets and survival rates of the elderly in Japan. DATA SOURCES AND STUDY DESIGN: This study is a population-based cohort study of the elderly in 16 municipalities in Japan. The study population included, those 60 years and over. Data were collected through self-administered questionnaires consisting of closed-ended question items. The response rate was 78.1% (=23,826/30,521). A total of 20,551 responses were included for analysis in this study. Surveys from those under 59 and incomplete responses were excluded due to data inconsistency. These items included whether or not they took care of a pet, annual income, lifestyle and subjective health status. The questionnaires were sent to follow the survival rates of those surveyed for two years, 1999-2001. A path analysis was used to assess the predictive validity of the factors included in the study and to establish the structural relationship between these factors and survival days. FINDINGS: 38.0% of men and 37.6% of women surveyed took care of pets. A strong relationship between caring for pets and cumulative survival rates is shown for the elderly surveyed. By using Cox’s regression model, caring for pets was identified as a significant factor to predict the survival days of the elderly. Survival days were directly prolonged by caring for pets and indirectly supported by the annual income of those surveyed. FUTURE ISSUES: This study suggests that caring for pets by the elderly as means to prolong the survival days receive greater attention. However, future studies are necessary to clarify the structural, causal relationship between elderly survival rates and caring for pets. Additionally, there is a need to establish external validity by conducting random sampling surveys in other cities.

Keywords: Caring for pets, Cumulative survival rate, Pass analysis, Elderly dwellers

Cite this paper: Tanji Hoshi , Maasa Kobayashi , Naoko Nakayama , Miki Kubo , Yoshinori Fujiwara , Naoko Sakurai , Steve Masami Wisham , The Relationship between Caring for Pets and the Two-Year Cumulative Survival Rate for Elderly in Japan, American Journal of Medicine and Medical Sciences, Vol. 7 No. 3, 2017, pp. 156-164. doi: 10.5923/j.ajmms.20170703.09.

Article Outline

1. Preface

- Costs associated with social insurance (e.g. medical costs, pensions) are on the rise in Japan’s increasingly aging, childless society. To that end, the government announced “Innovation 25” (2007) [1], a long-term strategy that includes medium-term goals like shifting from a treatment-centric form of medicine and healthcare to one focused on prevention and promotion of health. The Japanese government also launched the “New Growth Strategy” in 2010 [2] as a means of turning the country into a health promotion center.Various projects promoting the maintenance of a healthy life, free of the need for medical/nursing intervention are underway. [3] Additionally, there is growing interest in raising QOL (Quality of Life) and in the Japanese concept of leading a fulfilling life [4, 5].The WHO’s health promotion strategy examines more than just the health impact of traditional healthcare and welfare. They also emphasize the importance for other fields like education, transport, residential living, urban planning, industry, and agriculture to be to be considered in issues relating to health [6]. The Canadian Lalonde Report and US Department of Health’s “Healthy People” [7] indicate that healthcare contributes only 10% to overall-health, while lifestyle habits contribute 50% and living environment 20%. Other global data also serve to emphasize this need to go beyond the traditional healthcare model in improving overall-health and quality of life. There is now considerable research supporting the WHO’s [6] findings.Specifically, WHO findings show that securing education and social acceptance of efforts towards lifelong learning are essential in health promotion. Further they state that supporting the transport industry in promoting more outdoor trips; ensuring that residential contexts allow for family relationships and care of one’s appearance; that agricultural, forestry, and environmental conditions are maintained; and achieving a fulfilling life are other key areas [8-12].Kaplan et al [8] report that engaging in work, sports, and social networking can increase one’s expectancy of long life. Powe et al [9] have studied the significance of environmental protection for its implications in maintaining life. They report that a group living in a rich forest climate had a decreased sympathetic nervous system reaction compared to a control group [10]. The relationship between people and nature [11] is gaining more attention. For example, “forestry medicine” [12], a systematized means of therapy using the health benefits of the forest environment has been cited for its therapeutic efficacy.There are also reports of the contribution that raising dogs and cats can have on one’s health [13-16]. Kobayashi [13] conducted semi-structured interviews of nine subjects raising dogs in order to elucidate its health benefits. The results, described in a qualitative report, found that raising a dog provided a companion for a healthy lifestyle (rebuilding a lifestyle with a dog) (parenthesis denote categories), through which (responsibility for others developed) and a health outcome in which (a dog became a companion implicated in healthy activities). (The subject was put at ease by the presence of the dog). (The dog became an invaluable presence in the subject’s life). (The dog brought the family together). (The dog inspired an interest in others).There are also quantitative research reports on the healthful effect of raising a pet. [14-16] Hayakawa et al [14] report that raising a dog significantly increased physical activity of the caretaker versus activity in a control group. Saito et al [15] report that, in a questionnaire of 339 subjects aged over 65, 118 (30 percent) were raising a dog, and this group maintained IADL (Instrumental Activity of Daily Living) levels versus subjects with no experience raising a dog. Furthermore, there are reports of pet-like robots having a calming effect on the elderly and helping prevent depression. Suzuki et al [16] report that, in a study of six elderly subjects who had raised animals before, using a Pet Robot one hour every day for four weeks produced Mini-Mental State Examination(MMSE) levels that increased slightly from the average of 27.2 to 28.2, and a significant decrease in Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) levels from 6.7 to 3.5. There was also a decreased need for nursing intervention.By contrast, there have also been reports of negative effects on health produced by raising a pet, such as allergic symptoms, and respiratory, skin, and digestive ailments. [17-19] Ban et al [17] report that, while raising a pet can have therapeutic effects, it is also one factor in increased risk of asthma. Okumura et al [18] report that positive skin reactions in epidermal antibodies when raising a cat or dog were significantly higher in asthmatic populations. They also report that there was a significant correlation between raising rabbits and hamsters and suffering from respiratory tract inflammation in a survey of university students.Though not entirely without negative impact in some cases, the physical, mental, and social benefits of raising pets are becoming amply and increasingly clear. An important issue that requires elucidation is the relationship between pet ownership verses actually caring for pets, and how this distinction between simply owning pets vs. caring for them impacts lifestyle. Most significantly, there has been no prior research in Japan or elsewhere, on the correlation between actually caring for pets (as opposed to not caring for pets) and survival rates; the most important metric of health.This research study utilized a self-administered questionnaire given to people living in 16 municipalities nationwide. Our aim was to elucidate the factors correlated with both owning cats or dogs and the degree of care given to cats or dogs, with the cumulative survival rate obtained after two years.

2. Subjects and Methodology

2.1. Subjects and Survey Region

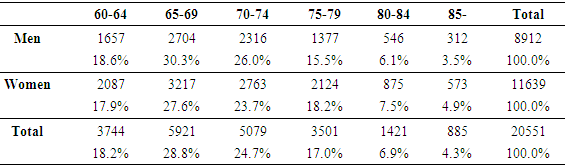

- Subjects for this research were elderly living in 16 municipalities, nationwide (Japan). Subjects totaling 23,286, were given a questionnaire between December 1998 and April 1999, (23,826/30,521=78.1%). Of these, incomplete responses and those falling under 59years, totaling 3,275 persons, were excluded, bringing the total to 20,551 (Table 1).

|

2.2. Analysis Methodology

- For this study, we used descriptive and analytical epidemiology. SPSS22.0J and AMOS22.0 for Windows were used as analytical tools. Statistical analysis was performed using χ2 and a Kendall test, with a p-value of 5%. Cumulative survival levels measured by ratio of care for dogs and/or cats were analyzed using Kaplan-Meier survival estimates. In order to establish comprehensive survival days, the Cox proportional hazards model was used. Further, in order to elucidate the structural correlation between the various factors underlying survival rate, path analysis was used.

3. Research results

3.1. Factors Correlated with Degree of Care of Cats or Dogs, by Sex

- The survey found that 38.0% of elderly men and 37.6% of elderly women residing in these regions owned cats or dogs. Furthermore, of those caring for pets, 45.9% reported “always” caring for them, 21.7% reported “sometimes” caring for them, 13.3% reported “seldom” caring for them, and 19.1% reported “never” caring for them.The groups were divided into those caring for and those not caring for cats or dogs (both those caring for and those not caring for cats or dogs were cat and dog owners). The correlation of various factors was analyzed. The results found that the group caring for cats or dogs had a statistically significant greater rate of subjective feelings of good health than did the group not caring for cats or dogs. The group owning but not caring for cats or dogs had statistically significant higher levels of satisfaction with their lives, engagement in hobbies and high wages compared to non-owners. However, no statistically significant correlation was found in rates of going outside. These findings suggest that merely owning cats or dogs does not have an effect on increased rates of going outside.We next analyzed the correlation of various factors in the groups caring for cats or dogs, based on the degree of care performed. A statistically significant and progressive increase in rate of subjective feelings of health was found the more the cats or dogs were cared for. Further, the more the cats and dogs were cared for, the more the owners had statistically significant higher levels of satisfaction with their lives, engagement in hobbies, rates of going outside and high wages. There was no correlation found with increased rate of going outside by simply owning cats or dogs, there was a statistically significant increase in the rate of going outside the more the cats or dogs were cared for.

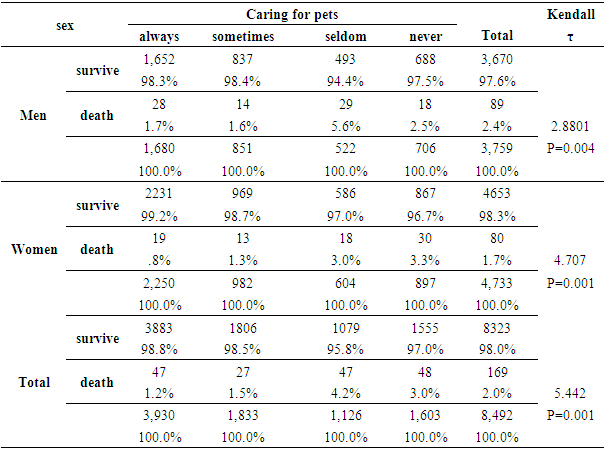

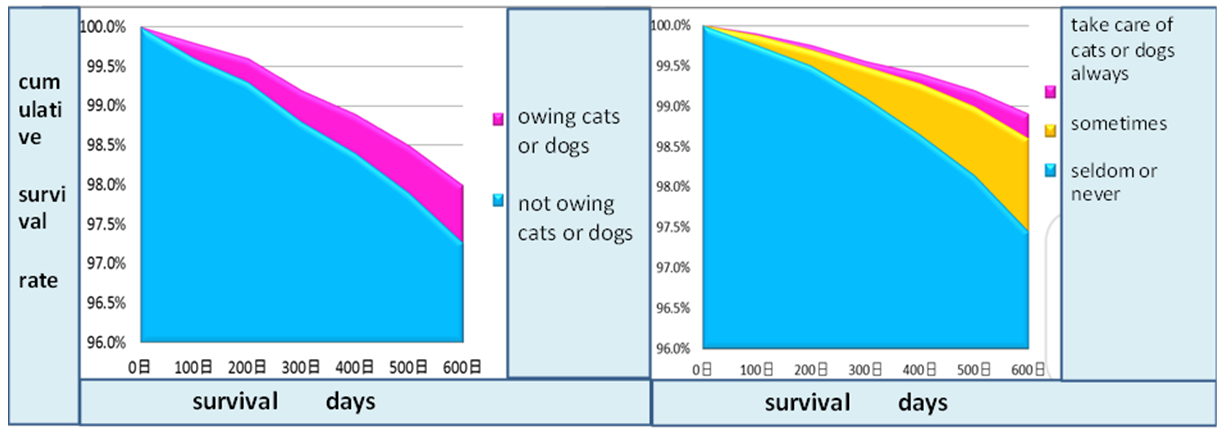

3.2. Correlation between Raising Cats or Dogs and Degree of Care and Survival Rate

- The statistical rate of survival two years later was significantly greater in the cohort who owned (but did not care for cats or dogs) compared to the cohort that did not own cats or dogs. However, no such significant difference was found when considering the male cohorts independently.The same correlation was analyzed, this time based on degree of care given to the cats or dogs. This analysis found that, the more care given to the cats or dogs, the more there was a statistically significant rate of survival two years later; this was true of both sexes(Table 2).

|

| Figure 1. Cummulative survival rate by the owing vs caring pets by Kapla Meier |

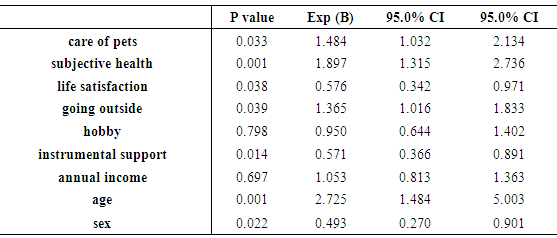

3.3. Cox Proportional Hazard Model as a Measure of Survival Days

- As noted previously, the female cohort who owned dogs or cats showed a statistically significant rate of maintenance of lifespan two years later compared to the cohort who did not own cats or dogs. Both male and female cohorts showed statistically significant increased rates of survival two years later when looking at degree of care. In order to control for other factors and comprehensively analyze the survival span in days, we used the Cox proportional hazards model. This analysis found that, when considering factors for which there was a statistically significant correlation with survival days, there were also higher subjective feelings of health in women but not men, and in those of a younger age but not among the elderly. There was also a significant correlation with a greater rate of going outside, as well as greater rate of caring for cats or dogs, with survival days. By contrast, groups receiving greater degrees of assisted living support showed a significantly lower rate of survival in days. No statistically significant difference was found between annual income and engagement in hobbies with lifespan in days.Sorting the results of the Cox proportional hazard model by sex found that those who owned cats or dogs had a statistically significant correlation with lifespan in days among women but not among men (Table 3).

|

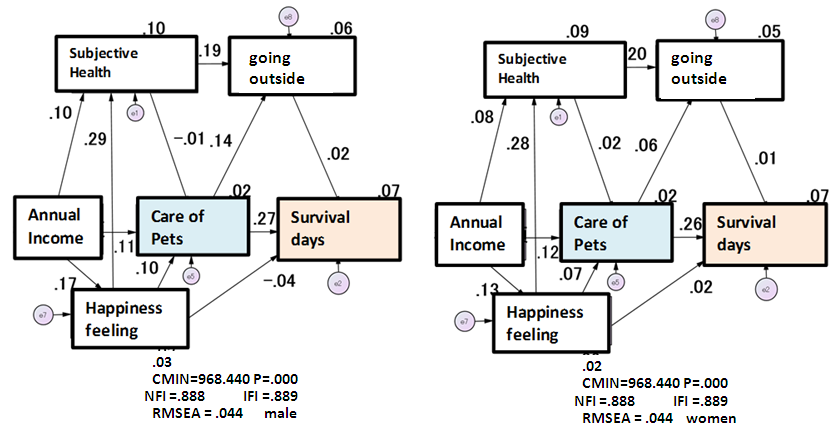

3.4. Pass Analysis of Two Years Survival Days by Several Factors

- Cohorts which actively cared for dogs or cats verses simply owning dogs or cats, showed greater rates of survival, particularly among women. There was also a significant correlation with lifespan in days for those actively caring for cats or dogs, even while controlling for other factors. Given this, we used a Pass analysis in order to elucidate the correlative relationship of each factor with lifespan in days.Annual income as a metric of degree of care of cats or dogs had high applicability (NFI=0.888, IFI=0.889, RMSA=0.044) in defining lifespan in days as the final outcome of maintenance of subjective feelings of health, and of frequency of going outside. This was true in both male and female cohorts.The factor most directly implicated in survival days is caring for cats or dogs. The factor most indirectly implicated in survival days is annual income. These factors remained largely the same even when dividing results by sex. The degree of care given to cats or dogs being implicated in rate of going outside as a standardized value was greater in men (0.140) than in women (0.06), though no significant difference was found statistically (Fig 2).

| Figure 2. Pass analysis of two years survival days by several factors |

4. Discussion

4.1. Factors Correlated with Degree of Care of Cats or Dogs

- The results showed that close to forty percent of elderly residents of these regions own cats or dogs. These findings support the work of Saito et al [15], who indicated that thirty percent of elderly persons over age sixty-five own dogs. Research by Koshimura [21] found that the rate of dog and cat ownership was 15.1% and 10.1% respectively. This is consistent for all age groups across the population. While the regions and age groups surveyed in Koshimura’s work differ from ours, our survey suggests that these conditions are largely consistent.Our survey also elucidated the degree of care given to cats or dogs. The combined total of those “always” caring for their cats or dogs and those “sometimes” caring for their cats or dogs was 67.6%. There was also a population of 19.1% of respondents who own cats or dogs but seldom or never care for them. Given that these details have not been reported in prior research, they will need to be replicated in order to ensure their validity.In addition to elucidating whether subjects owned cats or dogs and to what degree they cared for them, this research also elucidated factors correlated with said dog or cat ownership compared with the health impact of actual care given to them. We discovered a significant statistical basis for findings that rates of going outside cannot be maintained through the ownership of cats or dogs alone, and that the amount of care given to cats or dogs is essential to impacting the rates of going outside. This is a new finding, so it must be further validated and examined from the context of raising animals both in and out of doors.The White Paper on Household Animals, the first of its kind in Japan [21], found that the number of cats or dogs owned in Japan exceeds that of children under age fifteen. This research can be expanded on by scientific investigations into the rate of animal ownership, by type of animal, sex, and age of animal and by the degree of care given. This data can be correlated with subjective feelings of health in the owner, and with the frequency of going outside. Further, this data can reveal whether the animal and human populations have greater survival rates when living together.

4.2. Correlation between Raising Cats or Dogs and Survival Rate

- In our research, only the female cohort showed greater rates of survival when comparing those who owned cats or dogs versus those who did not. However, both the male and female cohorts that took active part in caring for their cats or dogs showed greater cumulative survival rates than those that did not take part in their care. Even when controlling for other factors, caring for cats or dogs proved to be a highly effective standalone metric for evaluating the correlation in women with rate of survival in days. Further, the degree of care given to cats and dogs, as supported by annual income in both men and women, supports the maintenance of subjective feelings of health and degree of going outside. These factors ultimately contribute to increased lifespan in days. This is the first time results of this nature have been reported.While annual income level is not directly implicated in lifespan in days, caring for cats or dogs is implicated in lifespan in days and is indirectly impacted by income level. Securing a greater annual income enables coexistence with pets and dogs and translate to the motivation to have affection for the animal. Our research suggests that this has major significance in creating a foundation for care.Owning cats or dogs and caring for them correlate with lifespan. Further, owning and caring for cats or dogs can be determined by socioeconomic factors. Therefore, to effectively promote health education among aged people, we should include the socioeconomic status of the individual as a basic factor in our analysis.Another factor implicated in lifespan was self-rated subjective feelings of health. Kaplan et al [8] surveyed 6,921 subjects aged sixteen and older for nine years to demonstrate the correlation between subjective feelings of health and mortality. This correlation was controlled for by age, sex, physical health, healthy lifestyle habits, social networks, income, education, and morals. This showed that even when controlling for feelings of happiness and other factors, subjective feelings of health were the most implicated in prognosis of life expectancy. This study supports the prior work of Kaplan et al [8] and Sugisawa et al. [22] Further, subjective feelings of health were maintained by caring for cats or dogs. The correlation of this factor in contributing to ultimate continued lifespan needs to be further tested to evaluate its results.As an example of local activities and volunteer work, which function as one form of social network, there is the possibility caring for cats or dogs and not simply owning them, can increase opportunities for going outside, and can therefore offer opportunities for increased interaction with society. While this research found that the degree of going outside, correlated with caring for animals, and contributed to an increase in lifespan in days, there was no statistically significant difference in the correlation of other local activities and hobbies with lifespan. These findings call for further research.Berkman et al [23] have done work on follow-up research on the correlation between social networks and mortality. Munakata [24] also divides social support into emotional support categories like peace of mind, trust, intimacy, self-worth, and hope; and instrumental support like assistance, money, articles, and information. Our research found that the more support there is from the surrounding network, the lower the rate of survival. We believe this because the worse the physical condition of the person, the more support is needed. Kitamura et al [25] have reported that physical activity is implicated in survival, and Sugisawa et al [26] have similarly reported that continuous and frequent physical activity may be implicated in survival. We believe that this research shows the significance of maintaining physical ability and not relying on others, in maintaining a longer lifespan. Future large-scale surveys could demonstrate the great potential caring for pets has in motivating more time spent outside and in increasing overall physical activity, and thereby aiding maintenance of physical health. Raising cats and dogs as one aspect in comprehensive healthcare is gaining attention. Atsumi [27] has organized the first conference of the Society of Integrative Medicine Japan, showcasing the latest trends in CAM (Complementary and Alternative Medicine) worldwide. CAM refers to alternative forms of medicine like animal therapy, chiropractory, Chinese medicine, Ayuverdic medicine, psychotherapy, visualization, qigong, nutritional therapy, and aromatherapy. There are close to 100 forms of CAM medically cited by the WHO. The conference has demonstrated how trends are moving towards comprehensive integration of Western, Eastern, and alternative medicines.Sekijima et al [28] have reported on the various alternative and comprehensive medical treatments underway in the US and how medical organizations and individuals are engaged in a wide range of fields to this end. Imanishi et al [29] report on the need for informatics databases in promoting better forms of alternative medicine. Watts et al [30] have reported that the State of Washington has amended its laws to expand complementary and alternative medical services making them available to more people.Acupuncture has been incorporated in the insurance and healthcare system In Britain. Spa therapy and forest treatment are part of the healthcare system in Germany and are used to promote good health and prevention of illness. These alternative methods are also used for hospice care. [12] We believe that this research has yielded scientific evidence that can be used to lend significance to animal-based interventionary care especially as it relates to the promotion of a longer lifespan. In the near future, we expect that animal therapy will be incorporated into Japanese insurance and health care systems.

4.3. Major Future Research Issues

- This research found that close to forty percent of the elderly population in Japan owns cats or dogs and, while simply owning a cat or dog did not suffice in contributing to health, taking part in the care of the pet contributed to greater rates of going outside, which ultimately contributed to longer lifespans. This is the first time a correlation of this type has been shown. While annual income cannot be pointed to directly in determining lifespan in days, it can be used to indirectly determine this.We believe there is a low degree of random error in these results. However, fewer questionnaire responses were collected from women than from men and from those over 70 years of age than from those younger. Therefore, these results may show some bias towards men and those between 50 and 70 years old.Furthermore, the survey regions were not sampled at random, so future approaches should include randomly sampling regions and subjects. Long-term studies to increase the external validity of these findings would also be important.While this research suggests the way in which owning cats or dogs and caring for them can contribute to the longer lifespan for the elderly, the underlying mechanisms by which they do so remain unexplained. In order to understand the essence of mechanisms supporting longer life, the most important future research should elucidate the neurological, biological, and biochemical impact which feelings of affection for a pet produce. Specifically significant would be how affection for a pet may increase brain hormones, activate the parasympathetic nervous system, stabilize blood pressure, and maintain subjective feelings of health. Further research should also call for surveys which measure the type and effectiveness of support systems and psychological care for those who lose their pets. Importantly, Koneko [31] has reported that companion animals (CA) can decrease owners’ subjective feelings of health and happiness, so future research is needed to clarify these conflicting reports.In the near future, additional interventional research involving caring for cats or dogs could be used in substantive epidemiology trials to elucidate to what extent companion animals are a factor in promoting health and long life. That is not to say there hasn’t been a body of outstanding interventional research reported thus far. For example, Ogawa [36] randomly sampled twelve healthy university subjects to report on factors of workplace stress and fulfillment based on seven data samples of feelings. These included samples upon immediately entering the testing room, when engaging in a task, and before and after a break with pets. The research showed significantly greater levels of fulfillment after the break with a pet. These findings suggest that intervention with pets may contribute to the alleviation of workplace stress.Future interventional research used to identify health and long life in animals and humans can be performed through analyses which explicitly divide dog and cat cohorts, and other pets. This research should analyze the degree of care given to the pet and not be limited to the simple ownership of pets. An additional long-term survey spanning two or more years should be done, with factors leading to death being divided into discreet categories. Identifying concurrent validity with QOL factors [33, 34] will be another future issue for this research.

4.4. Future Outlook of Impact of Raising Pets on Health

- While some prior research has reported on the negative effects of [17-19] raising pets on health, there are also reports which demonstrate pets can contribute to a calmer lifestyle. [35-38] Onogawa et al [35] surveyed 1,911,305 residents of Tokyo for an approximately six year period starting in January 1980, looking for the presence of Salmonella bacteria in their stool. 2,615 persons (0.14%) were found to be carrying the bacteria. These carriers were found to be raising turtles, dogs, or cats. This large-scale report indicates that zoonotic infections are not common. There have also been reports showing that bacteria from the stool of dogs with diarrhea do not infect their human owners. Takayama et al [36] performed stool sampling of 21 groups of dogs and their owners; stool cultures tested negative for shigella, Campylobacteria, and Salmonella. They reported that the potential for harmful infections caused by diarrhea-born bacteria in dogs infecting their owners is extremely low. Okada et al [37] also visited the Fukui Prefectural Health Promotion Office, the Fukui Prefectural Institute of Public Health and Environmental Science, and the Fukui Prefectural Health and Sanitation Center between late April 2004 and the end of July 2004 and collected literature and held interviews concerning zoonotic diseases. They reported that no major incidents had occurred in the prefecture. Further research will require surveys that distinguish between disease carrying, infection, symptoms, and manifestation.Other reports also find that domesticated pets living in better living conditions among humans had an extremely low rate of disease from enteric viruses. Sugieda et al [38] surveyed 138 domesticated dogs and 57 domesticated cats in order to evaluate the state of zoonotic disease and attempted to categorize these as enteric viruses and diarrhea-based viruses. Adenoviruses, Coxsackie B virus, and polio virus were isolated, but ECHO virus was not, suggesting that if pets live in better domesticated conditions among humans, the rate of enteric viruses and infections is extremely low.Coexisting with animals requires a self-care and public accountability support structure for individuals and families. Hosono [39] surveyed 403 children with bronchial asthma and their parents/guardians using a written questionnaire, and discovered that one particularly pressing issue is the need to create a foundation which would be a resource for these people to autonomously engage in better health management. The same can be said of epidermal ailments. Ikeda et al [40] report on a recent outbreak of scabies in hospitals and centers for the care of the elderly, and point out the need to properly apprehend this for the risk it poses.While there are a range of health-related issues, Muranaka [41] reports on the significance of efforts made by veterinary societies, (under the Comprehensive Regional Care System, supported by the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare) to create social systems for the support of the elderly raising animals and the impact of this activity in promoting longer life. Furthermore, Kumasaka et al [42] conducted QOL projects at hospitals that invited patients to engage with animals. 81% of participants in the projects responded that they liked animals. Whereas, 69% of nurses who utilized animals in treatment replied that they were“effective”. Kumasaka et al thus report that these animal-experience events would prove viable at hospitals.Kumei et al [43] report mites as one causative factor in atopic dermatitis. Analysis of mite populations and residential reforms have found the importance of using wooden flooring and heated floors and in particular, the importance of not placing carpets on top of tatami mats in preventing mite infestation. Saijo et al [44] report on the need to be aware of chemical substances and humid climates implicated in sick building syndrome. Additionally, they point out that medical examinations must not only incorporate subjective symptoms and detailed questions on environmental factors, but that living environments must be analyzed as well. Furthermore, as Sato et al [45] indicate, if accurate preventive measures based on knowledge of the means of infection in zoonotic diseases, pathogens, and host animals are employed, more enjoyable and healthy lives with pets could be achieved. Koshimura [20] indicates that medical societies are seriously promoting ways of increasing pet and human QOL (quality of life), sharing useful information with prefectural and municipal governments, educational organizations, and citizens, thereby decreasing medical costs and contributing to the mental and physical wellbeing of people through the creation of new healthcare industries, educational industries, and “peace” industries, ultimately driving the creation of what could be called “happiness creation industries.” In this way, it may be possible to create a new form of social value towards the creation of a society in which humans and animals can better coexist.

Abstract

Abstract Reference

Reference Full-Text PDF

Full-Text PDF Full-text HTML

Full-text HTML